Abstract

Abstract

Galantamine is one of several orally administered cholinesterase inhibitors that improve cognition in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Compared with placebo, galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day improved cognition and activities of daily living, delayed emergence of behavioural symptoms and reduced caregiver burden in three pivotal randomised studies of 5 or 6 months’ duration.

Galantamine may reduce the considerable economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease by delaying the need for full-time care (FTC) in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. In pharmacoeconomic analyses with a time horizon of 10 years conducted in Canada, Sweden, The Netherlands and the US, data from the pivotal trials were incorporated into a model to examine economic implications associated with galantamine treatment. FTC was defined in the model as the consistent requirement for caregiving and supervision for the greater part of each day regardless of the location of care and the identity of caregiver. When the effect of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day was analysed from the perspective of a comprehensive healthcare payer, treatment was associated with cost savings (inclusive of drug costs) relative to no treatment, regardless of country for which the model was customised. Cost savings resulted from the delay in the time until FTC was required in patients with mild to moderate disease. In sensitivity analyses, cost savings were most sensitive to the cost of institutional care.

In the analyses that considered the effect of galantamine 24 mg/day solely on cognition, galantamine was predicted to reduce the time FTC was required by ≈10% in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease compared with no pharmacological treatment. Greater reductions in the time that FTC was required were predicted when the effects of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day on behavioural symptoms in addition to cognition were considered in the US analysis or in sensitivity analyses in studies in other countries.

In conclusion, pharmacoeconomic analyses, which were based on modelling of data from pivotal clinical trials with galantamine and included drug costs, indicate that galantamine treatment may result in cost savings from a healthcare payer perspective. The effects of galantamine on cognition and behavioural symptoms in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease are predicted to delay the need for FTC, which may result in cost savings. From a societal perspective, the caregiver burden of caring for a patient with Alzheimer’s disease in the community may be decreased and the time that patients have without severe disease may be prolonged.

Alzheimer’s Disease

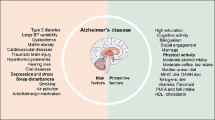

Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterised by progressive loss of cognition, a decline in the ability to perform activities of daily living and the development of behavioural symptoms, is the most common form of irreversible dementia. The average prevalence is ≈5% in those aged 65 years and older. Although there are other possible risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. family history of dementia, presence of Down’s syndrome), age is the most relevant risk factor.

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a considerable cost burden, regardless of whether costs of formal, informal or formal plus informal care are included. In the US, Alzheimer’s disease is considered to be the third most costly disease and is estimated to cost approximately $US80 to $US100 billion per year. Although public and private healthcare insurers carry many of the direct costs of Alzheimer’s disease, patients and their families bear many other expenses. In the early stages of the disease, patients often live at home; as the disease progresses and patients become increasingly dependent on the care of others, they are placed in institutions. Because the estimated costs of caring for a patient with Alzheimer’s disease are lower when care is given in the community than when given in institutional facilities, a substantial increase in costs is associated with the decision to move a patient from the community to institutionalised care. Due to the increased need for care and supervision, the costs of Alzheimer’s disease generally increase as the severity of disease increases.

The current focus of symptomatic treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease is augmentation of cholinergic neurotransmission to delay further deterioration in cognitive abilities and behaviour and to increase functional performance. Several orally administered cholinesterase inhibitors (galantamine, donepezil, rivastigmine and tacrine) are now available and all achieve improvements in cognition in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Unlike the other cholinesterase inhibitors, galantamine also allosterically modulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. The choice of therapy in the individual patient may be influenced by differences in improvement of symptoms other than cognition, and by the pharmacological, tolerability and administration profiles of these agents.

Therapeutic Use of Galantamine

Compared with placebo, galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day improved cognition and activities of daily living, delayed the emergence of behavioural symptoms and reduced caregiver burden in three pivotal randomised studies of 5 or 6 months’ duration.

In these trials, galantamine significantly improved cognition compared with placebo (differences in favour of galantamine were 3.1 points for the galantamine 16 mg/day group and 2.9 to 3.9 points for the galantamine 24 mg/day groups) as measured by the 11-item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog). Moreover, improvements of >-4 points in ADAS-cog were shown by a significantly greater proportion of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day recipients than placebo recipients. Galantamine was also superior to placebo on the Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change plus Caregiver Input scale, which measures global functioning.

Treatment with galantamine may have beneficial effects on some aspects of instrumental and basic activities of daily living as measured in the pivotal trials. One of these trials also included measurement of behavioural symptoms and showed that galantamine significantly delayed the development of behavioural symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared with placebo.

The cognitive and functional benefits of galantamine result in a reduction in caregiver burden. Preliminary results from one study showed that no additional caregiver supervision and less time with assistance with activities of daily living was required by galantamine 24 mg/day recipients after 6 months’ treatment compared with baseline.

The adverse events most commonly associated with galantamine, as with other cholinesterase inhibitors, are cholinergic in nature. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, weight loss and anorexia, and were reported by 6 to 17% of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day recipients and 1 to 6% of placebo recipients in the 5-month pivotal trial, which used the recommended 4-week dose escalation regimen. Most events were transient and of mild to moderate severity. Treatment was discontinued due to adverse events in 7 and 10% of galantamine 16 and 24 mg/day recipients and 7% of placebo recipients. No clinically relevant changes in laboratory values (including hepatic enzymes) or vital signs were observed in the pivotal trials.

Pharmacoeconomic Analyses of Galantamine

Potential cost savings may occur if patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease receive a drug, such as galantamine, that slows the decline in cognition and the development of behavioural symptoms, and thereby delays the need for full-time care (FTC) in an institution or at home. FTC is defined as the consistent requirement for caregiving and supervision for the greater part of each day regardless of the location of care or identity of the caregiver. The Assessment of Health Economics in Alzheimer’s Disease (AHEAD) model uses algorithms to predict the time until FTC is required or death occurs in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Index scores for five characteristics shown to be predictors of the need for FTC in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and four characteristics predictive of death are incorporated in the model.

By incorporating key clinical data from pivotal clinical trials of galantamine, the AHEAD model has been customised to estimate the long-term health and cost implications of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day treatment compared with no pharmacological treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Canada, Sweden, The Netherlands and the US. Each analysis had a time horizon of 10 years and was conducted from the perspective of a comprehensive healthcare payer. Costs of formal care (e.g. medical and home help costs) and the proportions of patients requiring FTC that would receive FTC in institutions were derived from recent data corresponding to the locality of the analysis.

Relative to no treatment, cost savings (inclusive of drug-related costs) with galantamine were predicted regardless of the country for which the model was customised, and resulted from the reduction in the time patients required FTC. Most base analyses considered the effect of galantamine 24 mg/day solely on cognition; galantamine reduced the time FTC was required by ≈10% in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, and by ≈11% in the subgroup of patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease. It was predicted that 5.6 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease or 3.9 patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease need to start treatment with galantamine 24 mg/day to prevent 1 year of FTC.

The US analysis, which included the effect of galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day on both cognition and behavioural symptoms, predicted that cost savings and increased time until FTC was required would result with galantamine.

Because patients with moderate disease need FTC sooner than those with mild disease, cost savings were calculated to be greater in the subgroup of patients with moderate disease than in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

In the sensitivity analyses, cost savings varied depending on the input of reasonable changes in key parameters. Results were most sensitive to the cost of institutional care; the proportion of patients requiring FTC in an institution and the acquisition cost of galantamine were other important variables. Total cost savings in the Dutch or Canadian analyses were predicted to increase by ≈60 or 100%, respectively, when the effects of galantamine 24 mg/day on behavioural symptoms in addition to the effect on cognitive symptoms were considered in sensitivity analyses (using data from the pivotal galantamine trial that addressed behavioural symptoms).

Using the same economic model, preliminary results of a Canadian analysis favoured galantamine 16 or 24 mg/day over donepezil 5 or 10 mg/day or low- or high-dose rivastigmine in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in a comparison of predicted costs and time patients required FTC. This analysis, which had a 10-year time horizon, incorporated data from Cochrane meta-analyses of pivotal trials of the three cholinesterase inhibitors into the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Scott LJ, Goa KL. Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 2000 Nov; 60 (5): 1095–122

Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Amaducci L. Epidemiology of dementias. Drugs Today 1998 Sep; 34: 747–58

Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders: consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA 1997; 278: 1363–71

Keefover RW. The clinical epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 1996; 14: 337–51

Parnetti L, Senin U, Mecocci P. Cognitive enhancement therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. The way forward. Drugs 1997; 53 (5): 752–68

Guttman R, Altman RD, Nielsen NH. Alzheimer disease: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Arch Fam Med 1999; 8 (4): 347–53

Evans DA, Churchill LA, Hillman KC, et al. Estimated prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Milbank Q 1990; 68 (2): 267–93

Carr DB, Goate A, Phil D, et al. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med 1997; 103 (3A): 3–10

Costa Jr PT, Williams TF, Albert MS, et al. Recognition and initial assessment of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Guideline Panel. Rockville (MD): US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996 Nov; AHCPR publication 97-0702

Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1997; 278: 1349–56

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease [online]. Available from URL: www.nice.org.uk/pdf/ALZHEIMER_full_guidance.pdf [Accessed 2002 May 13]

American Psychiatric Association Clinical Resources. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias of late life [online]. Available from URL: http://www.psycho.org/clin_res/pg_dementia.cfm [Accessed 2002 May 6]

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, et al. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriat Soc 1998; 46: 210–5

Winblad B, Brodaty H, Gauthier S, et al. Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease: is there a need to redefine treatment success? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16 (7): 653–66

Meek PD, McKeithan EK, Schumock GT. Economic considerations in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18 (Pt. 2): 68S–73S

Rice DP, Fillit HM, Max W, et al. Prevalence, costs, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia: a managed care perspective. Am J Manag Care 2001 Aug; 7: 809–18

Max W. Drug treatments for Alzheimer’s disease: shifting the burden of care. CNS Drugs 1999; 11: 363–72

Taylor Jr DH, Schenkman M, Zhou J, et al. The relative effect of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, disability, and comorbidities on cost of care for elderly persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2001 Sep; 56 (5): S285–93

Ernst RL, Hay JW. Economic research on Alzheimer disease: a review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11 Suppl. 6: 135–45

Max W, Webber P, Fox P. Alzheimer’s disease: the unpaid burden of caring. J Aging Health 1995; 7 (2): 179–99

Winblad B, Hill S, Beerman B, et al. Issues in the economic evaluation of treatment for dementia: position paper from the International Working Group on Harmonization of Dementia Drug Guidelines. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997; 11 Suppl. 3: 39–45

Small GW, McDonnell DD, Brooks RL, et al. The impact of symptom severity on the cost of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002 Feb; 50 (2): 321–7

Wilkinson D. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: the impact of cholinesterase inhibitors. CPD Bulletin Old Age Psychiatry 2001; 2 (3): 76–9

Wimo A, Winblad B, Grafstrom M. The social consequences for families with Alzheimer’s disease patients: potential impact of new drug treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999 May; 14 (5): 338–47

Leon J, Cheng C-K, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer’s disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998; 17: 206–16

Hux MJ, O’Brien BJ, Iskedjian M, et al. Relation between severity of Alzheimer’s disease and costs of caring. CMAJ 1998 Sep 8; 159: 457–65

Souêtre E, Thwaites RMA, Yeardley HL. Economic impact of Alzheimer’s disease in the United Kingdom: cost of care and disease severity for non-institutionalised patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 1999 Jan; 174: 51–5

Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitor therapy stabilizes symptoms of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 2000; 14 Suppl. 1: S3–10

Grutzendler J, Morris JC. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 2001; 61 (1): 41–52

Cummings JL. Cholinesterase inhibitors: a new class of psychotropic compounds. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 4–15

Coyle J, Kershaw P. Galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor that allosterically modulates nicotinic receptors: effects on the course of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 2001 Feb 1; 49 (3): 289–99

Samochocki M, Zerlin M, Jostock R, et al. Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of the human α4/β2 nAChR. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2000; 176: 68–73

Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as a treatment strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 393: 165–70

Newhouse PA, Potter A, Levin ED. Nicotinic system involvement in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: implications for therapeutics. Drugs Aging 1997; 11: 206–28

Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Wessel T, et al. Galantamine in AD: a 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a 6-month extension. Galantamine US-1 Study Group. Neurology 2000; 54 (12): 2261–8

Wilkinson D. Galantamine: a new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics 2001; 1 (2): 89–95

California Workgroup on Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease Management. Guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease management [online]. Available from URL: http://www.alzla.org/medical/FinalReport2002.pdf [Accessed 2002 May 6]

Morris JC. Therapeutic continuity in Alzheimer’s disease: switching patients to galantamine. Overview. Clin Ther 2001; 23 Suppl. A: A1–2

Nordberg A, Svensson A-L. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison of tolerability and pharmacology. Drug Saf 1998; 19: 465–80

Weinstock M. Selectivity of cholinesterase inhibition: clinical implications for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 1999; 12 (4): 307–23

VanDenBerg CM, Kazmi Y, Jann MW. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2000; 16: 123–38

Tariot PN, Solomon PR, Morris JC, et al. A 5-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. Neurology 2000; 54 (12): 2269–76

Wilcock GK, Lilienfeld S, Gaens E. Efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Galantamine International-1 Study Group. BMJ 2000 Dec 9; 321: 1445–9

Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease therapy: from tacrine to future applications. Neurochem Int 1998; 32: 413–9

Gauthier S. Cholinergic adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology and management. Drugs Aging 2001; 18 (11): 853–62

Richards SS, Hendrie HC. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a guide for the internist. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 789–98

Doody RS, Steven C, Beck JC, et al. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001; 56: 1154–66

Janssen Pharmaceutica Products. Reminyl (galantamine) tablets and oral solution prescribing information. Titusville (NJ): Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, 2001 Oct

Raskind MA. Sustained cognitive benefits of galantamine in Alzheimer’s disease [abstract no. NR226]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; 2002 May 18–23 2002; Philadelphia (PA)

Rockwood K, Mintzer J, Truyen L, et al. Effects of a flexible galantamine dose in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001 Nov; 71 (5): 589–95

Erkinjuntti T, Kurz A, Gauthier S, et al. Efficacy of galantamine in probable vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002 Apr 13; 359 (9314): 1283–90

Tariot P, Kershaw P, Yaun W. Galantamine postpones the emergence of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a 5-month, randomised, placebo-controlled study [poster]. 7th International World Alzheimer’s Congress; 2000 Jul 9–18; Washington DC

Sano M, Sadik K. Galantamine reduces caregiver time assisting Alzheimer’s disease patients [abstract no. NR487]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 18–23 2002; Philadelphia (PA), 132

Lilienfeld S, Gaens E. Galantamine alleviates caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: a 12-month study [abstract no. P3111]. Eur J Neurol 2000 Nov; 7 Suppl. 3: 133

Blesa R. Galantamine: therapeutic effects beyond cognition. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002; 11 Suppl. 1: 28–34

Wilkinson D, Murray J. Galantamine: a randomized, double-blind, dose comparison in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Galantamine Research Group. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001 Sep; 16 (9): 852–7

DeJong R, Osterlund OW, Roy GW. Measurement of quality-of-life changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Ther 1989; 11 (4): 545–54

Stahl S, Markowitz DPH, Gutterman E, et al. No increase in sleep-related events with galantamine in Alzheimer’s disease [abstract no. NR483]. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; 2002 May 18–23 2002; Philadelphia (PA), 131

Vitiello MV, Borson S. Sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs 2001; 15 (10): 777–96

Ernst RL, Hay JW, Fenn C, et al. Cognitive function and the costs of Alzheimer disease: an exploratory study. Arch Neurol 1997 Jun; 54: 687–93

Leon J, Neumann PJ. The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in managed care: a cross-sectional study. Am J Manag Care 1999 Jul; 5 (7): 867–77

Caro JJ, Getsios D, Migliaccio-Walle K, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer’s disease (AHEAD) based on need for full-time care. Neurology 2001 Sep 25; 57 (6): 964–71

Getsios D, Caro JJ, Caro G, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer’s disease (AHEAD): galantamine treatment in Canada. Neurology 2001 Sep 25; 57 (6): 972–8

Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A, et al. Economic analysis of galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in the Netherlands. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002; 14: 84–9

Garfield FB, Getsios D, Caro JJ, et al. Assessment of health economics in Alzheimer’s disease (AHEAD): treatment with galantamine in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics 2002; 20 (9): 629–37

Caro J, Migliaccio-Walle K, Ishak KJ, et al. Economic impact of galantamine in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease [abstract no. 30]. Ann Neurol 2001 Sep; 50 Suppl. 1: S79

Migliaccio-Walle K, Caro J, Getsios D, et al. Economic benefits in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in the US: cognitive and behavioral effects of Reminyl (galantamine) [poster]. AHEAD Study Group. XVII World Congress of Neurology; 2001 June 17–22; London

Migliaccio-Walle K, Caro J, Ishak KJ, et al. The economic impact of galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease in the US [poster]. International Psychogeriatric Association Congress; 2001 Sep 9–14; Nice

Caro JJ, Getsios D, Migliaccio-Walle K, et al. A comparison of pharmacoeconomic outcomes with galantamine, rivastigmine and donepezil [abstract]. Neurology 2002; 58 Suppl. 3: A135

Stern Y, Tang M-X, Albert MS, et al. Predicting time to nursing home care and death in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA 1997; 277: 806–12

Caro J, Salas M, Getsios D, et al. Use of galantamine in the Netherlands for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease [abstract]. Value Health 2001 Mar–2001 30; 4: 153–4

Lopez OL, Becker JT, Wisniewski S, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment alters the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72: 310–4

Whitehouse PJ. Cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: are they worth the cost? CNS Drugs 1999; 11 (3): 167–73

Johnson N, Davis T, Bosanquet N. The epidemic of Alzheimer’s disease: how can we manage the costs? Pharmacoeconomics 2000 Sep; 18 (3): 215–23

Leon J, Moyer D. Potential cost savings in residential care for Alzheimer’s disease patients. Gerontologist 1999 Aug; 39 (4): 440–9

Post SG, Whitehouse PJ. Emerging antidementia drugs: a preliminary ethical view. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998 Jun; 46: 784–7

Fillit HM. The pharmacoeconomics of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Manag Care 2000 Dec; 6 (22 Suppl.): S1139–44; discussion S1145-8

Ferris SH. Switching previous therapies for Alzheimer’s disease to galantamine. Clin Ther 2001; 23 Suppl. A: A3–7

Lamb HM, Goa KL. Rivastigmine: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19 (3): 303–18

Foster RH, Plosker GL. Donepezil: pharmacoeconomic implications of therapy. Pharmacoeconomics 1999; 16 (1): 99–114

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lyseng-Williamson, K.A., Plosker, G.L. Galantamine. Pharmacoeconomics 20, 919–942 (2002). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200220130-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200220130-00005