Abstract

Objective: To determine the cost effectiveness of adjunctive therapy with entacapone versus standard treatment (levodopa) without entacapone for patients in the US with Parkinson’s disease (PD)who experience ‘off-time’ (re-emergence of the symptoms of PD) while receiving levodopa.

Study Design: A Markov model was used to estimate 5-year costs and effectiveness of standard treatment with and without entacapone.

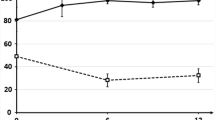

Methods: Probabilities, unit costs, resource utilisation data and utilities were obtained from published literature, clinical trial reports, a national database, and clinical experts. PD disability was measured using the daily proportion of off-time and Hoehn and Yahr scale scores. The analysis measured costs from a societal and third-party payer perspective, and effectiveness as gains in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and years without progression to >25% off-time.

Results: From a societal perspective, entacapone therapy resulted in an incremental cost of $US9327 per QALY gained compared with standard treatment. Treatment with entacapone also provided an additional 7.6 months with ≤25% off-time/day compared with standard treatment. Sensitivity analyses indicated that the model is sensitive to changes in rates of improvement/deterioration of off-time, and to the number of doses per day of levodopa with adjunctive entacapone.

Conclusions: The addition of entacapone to standard treatment for patients receiving levodopa who experience off-time provides additional QALYs and gain in time with minimal fluctuations. Results of this modelling exercise suggest that therapy with entacapone may be cost effective when compared with standard treatment for PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The ‘pull test’ is a standard component of assessment of postural stability in Parkinson’s disease. It evaluates the response to sudden, strong posterior displacement produced by pulling on the shoulders while the patient is erect with eyes open and feet slightly apart. The patient is prepared.

References

Koller WC. Classification of parkinsonism. In: Koller WC, editor. Handbook of Parkinson’s disease. New York (NY): Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1987: 51–80

de Pedro-Cuesta J, Stawiarz L. Parkinson’s disease incidence: magnitude, comparability, time trends. Acta Neurol Scand 1991; 84: 382–8

Tanner CM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Clin 1992; 10: 317–29

Oertel WH, Quinn NP. Parkinsonism. In: Brandt T, Caplan LR, Dichgans J, et al., editors. Neurologic disorders: course and treatment. San Diego (CA): Academic Press, 1996: 715–72

Rajput AH, Offord KP, Beard CM, et al. A case-control study of smoking habits, dementia, and other illnesses in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1987; 37: 226–32

Parkinson Study Group. Mortality in DATATOP: a multicenter trial in early Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 1998; 43: 318–25

Yahr MD. Evaluation of long-term therapy in Parkinson’s disease: mortality and therapeutic efficacy. In: Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, editors. Advances in parkinsonism. Basel: Editiones Roche, 1976: 435–43

Hoehn MM. Parkinsonism treated with levodopa: progression and mortality. J Neural Transm 1993; Suppl. 19: 253–64

Uitti RJ, Ahlskog JE, Maraganore DM, et al. Levodopa therapy and survival in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Olmstead County project. Neurology 1993; 43: 1918–26

Bonnet AM, Marconi R, Vidailhe M, et al. Levodopa versus bromocriptine-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. New Trends Clin Neuropharmacol 1992; 6: 1–4

Marconi R, Lefebvre-Caparros D, Bonnet A, et al. Levodopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Phenomenology and pathophysiology. Mov Disord 1994; 1: 2–12

Scheife RT, Schumock GT, Burstein A, et al. Impact of Parkinson’s disease and its pharmacologic treatment on quality of life and economic outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000; 57: 953–61

Dodel RC, Singer M, Kohne-Volland R, et al. The economic impact of Parkinson’s disease: an estimation based on a 3-month prospective analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 14: 299–312

Baas H, Beiske AG, Ghika J, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition with tolcapone reduces the “wearing off” phenomenon and levodopa requirements in fluctuating parkinsonian patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 63: 421–8

Rinne UK. Problems associated with long-term levodopa treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 1983; 95: 19–26

Djaldetti R, Melamed E. Management of response fluctuations: practical guidelines. Neurology 1998; 51 Suppl. 2: S36-40

Chrischilles EA, Rubenstein LM, Voelker MD, et al. The health burdens of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 1998; 13: 406–13

Clarke CE, Zobkiw RM, Gullaksen E. Quality of life and care in Parkinson’s disease. Br J Clin Pract 1995; 49: 288–93

Montgomery EB, Lieberman A, Singh G, et al. Patient education and health promotion can be effective in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med 1994; 97: 429–35

Mercer BS. A randomized study of the efficacy of the PROPATH program for patients with Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53: 881–4

Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan F, Kulas E, et al. The burden of Parkinson’s disease on society, family, and the individual. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 844–9

Dodel RC, Pepperl S, Köhne-Volland R, et al. Medizinische ökonomie: kosten der medikamentösen behandlung neurologischer erkrankungen: morbus parkinson, dystonie, epilepsie. Med Klin 1996; 91: 483–5

Dodel RC, Eggert KM, Singer MS, et al. Costs of drug treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 1998; 13: 249–54

Rubenstein LM, Chrischilles EA, Voelker MD. The impact of Parkinson’s disease on health status, health expenditures, and productivity. Estimates from the National Medical Expenditure survey. Pharmacoeconomics 1997; 12: 486–98

Le Pen C, Wait S, Moutard-Martin F, et al. Cost of illness and disease severity in a cohort of French patients with Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics 1999; 16: 59–69

Hempel AG, Wagner ML, Maaty MA, et al. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of using Sinemet CR over standard Sinemet in parkinsonian patients with motor fluctuations. Ann Pharmacother 1998; 32: 878–83

Hoerger TJ, Bala MV, Rowland C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pramipexole in Parkinson’s disease in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 14: 541–57

Parkinson Study Group. Entacapone improves motor fluctuations in levodopa-treated Parkinson’s disease patients. Ann Neurol 1997; 42: 747–55

Rinne UK, Larsen JP, Siden A, et al. Entacapone enhances the response to levodopa in parkinsonian patients with motor fluctuations. Neurology 1998; 51: 1309–14

PhRMA Task Force on the Economic Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals. Methodological and Conduct Principles for Pharmacoeconomic Research. Washington (DC): Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, 1995

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al., editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 1996

Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortality. Neurology 1967; 17: 427–42

Decision analysis by Tree Age (DATA) Software, Version 3.14 for Windows [computer program]. Williamstown (MA): TreeAge Software, Inc., 1996

Beck JR, Pauker SG. The Markov process in medical diagnosis. Med Decis Making 1983; 3: 419–58

Barr JT, Schumacher GE. Using decision analysis to conduct pharmacoeconomic studies. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott-Raven; 1996: 1197–214

Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making 1993; 13: 322–38

Palmer CS, Schmier J, Snyder E, et al. Patient preferences and utilities for “off-time” outcomes in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res 2000; 9 (7): 819–27

Schlenker RE, Kramer AM, Hrincevich CA, et al. Rehabilitation costs: implications for prospective payment. Health Serv Res 1997; 32: 651–68

Health Care Consultants of America. 1999 physicians fee and coding guide. Augusta (GA): HealthCare Consultants of America, 1999

National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems. Trends in psychiatric health systems. 1995 annual survey: final report. Washington (DC): National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, 1995: 13

MEDTAP database of international unit costs. Berthesda (MD): Medtap International, 2001

Medical Economics Company. 1999 red book. Montvale (NJ): Medical Economics Company, 1999

Luce BR, Manning WG, Siegel JE, et al. Estimating costs in cost-effectiveness analysis. In: Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al., editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 1996: 202–3

Beck JR, Pauker SG, Gottlieb JE, et al. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the “DEALE”). II. Use in medical decision-making. Am J Med 1982; 73: 889–97

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, et al. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization?. Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ 1992; 146: 473–81

Nuijten MJC. The selection of data sources for use in modelling studies. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 13 (3): 305–16

Nuijten MJC. Bridging decision analytic modelling with a cross-sectional approach. PharmacoEconomics 2000 Mar; 17 (3): 227–36

Olanow CW, Shapira AHV, Rascol O. Continuous dopamine stimulation in early Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci 2000; 23: S117–26

Kieburtz K, Hubble J. Benefits of COMT inhibitors in levodopa-treated parkinsonian patients: results of clinical trials. Neurology 2000; 55 (11 Suppl. 4): S42–5

Hatziandreu EJ, Brown RE, Revicki DA, et al. Cost utility of maintenance treatment of recurrent depression with sertraline versus episodic treatment with dothiepin. Pharmacoeconomics 1994; 5 (3): 249–68

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation but was executed by MEDTAP, an independent reseach organisation. There was no conflict of interest for the authors.

We are grateful to Ariel Gordin, MD, PhD, Kari Reinikainen, MD, PhD, Mika Leinonen MSc, and Eeva Taimela, MD, PhD of Orion Pharma for providing clinical trial data and collaboration to MEDTAP. Additionally, we would like to thank the following individuals for their contribution to this study as members of the clinical panel: Jean Hubble, MD, Ohio State University Parkinson’s Disease Center of Excellence, Columbus, Ohio; Kapil Sethi, MD, Department of Neurology of the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, Georgia; Kelly Lyons, PhD, Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas; Ruth Hagenstuen, RN, MA, Struthers Parkinson Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Jonie Whitehouse, RN, BSN, Wisconsin Institute for Neurologic and Sleep Disorders, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. We are also grateful to the Parkinson Study Group (PSG) who participated in the study and to Melissa Kuehn and Barbara Godlew for their work in preparing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palmer, C.S., Nuijten, M.J., Schmier, J.K. et al. Cost Effectiveness of Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease with Entacapone in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics 20, 617–628 (2002). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200220090-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200220090-00005