Abstract

Assessment of the Quality-of-Life Implications of Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease

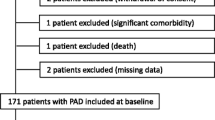

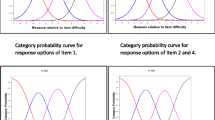

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is a common condition with possible serious consequences. It is usually diagnosed at the intermittent claudication stage. There are 2 objectives of treatment: to prevent ischaemic attacks and to improve quality of life. Treatment efficacy is, however, usually evaluated only in terms of walking distance. When making medical decisions, it is now generally accepted that patients are as much concerned by quality of life as by life expectancy, particularly with regard to chronic diseases for which the aim of therapy is not only to treat the disease but also to relieve pain or restore function. Quality-of-life evaluation is therefore necessary to assess treatment efficacy, guiding clinicians in their choice of therapy and manufacturers in their choice of new molecules for development. Three types of instruments can be used to evaluate quality of life. Currently, those most often used are health status and health-related quality-of-life scales. These scales can be nonspecific, giving information on both health status and quality of life independently of any particular condition [the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 items (SF-36), for example], or they may be relevant to one disease. Specific scales are usually more sensitive than nonspecific ones. When the ARTEMIS® scale, which is specific to peripheral arterial occlusive disease, was developed in 1993, there were 400 scales in existence. However, none were specific to peripheral arterial occlusive disease. The ARTEMIS® scale is a self-administered questionnaire, composed of a general (SF-36) and a specific instrument. It comprises 64 items covering the 8 dimensions of the SF-36, 5 specific dimensions and 2 differential dimensions (perception of health status evolution and perception of the future). The ARTEMIS® questionnaire was validated in 177 patients with intermittent claudication (phases IIa and IIb of the Leriche and Fontaine classification). Results obtained with the ARTEMIS® questionnaire are presented and compared with those obtained by other authors using nonspecific or specific scales for quality-of-life evaluation. All results showed that intermittent claudication has a significant effect on the various dimensions of quality of life (except in one study). Nevertheless, the relationship between walking distance (or other functional measures) and quality of life did not prove to be as close as had been expected, indicating that functional measures do not reflect the patient’s overall perception of the disease. The ARTEMIS® questionnaire showed that quality-of-life scores were significantly higher (better quality of life) in patients with walking distances greater than 500 metres than in those with shorter walking distances (less than 500 metres). Moreover, quality-of-life scores were both high and similar in patients with walking distances greater than 500 metres, while in patients with shorter walking distances quality-of-life scores ranged from high (good quality of life) to low (bad quality of life). In the absence of curative treatment, the patient’s perception of quality of life must therefore be evaluated prior to any treatment. Treatment will help to prevent ischaemic attacks in patients with walking distances greater than 500 metres, and will have a preventive effect and improve functional measures in patients with low quality-of-life scores, regardless of walking distance. The ARTEMIS® questionnaire can therefore assist clinicians in their choice of therapeutic strategy and in the evaluation of treatment efficacy.

Résumé

L’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs est une pathologie fréquente dont les conséquences peuvent être graves. Elle est généralement diagnostiquée au stade de la claudication intermittente. Son traitement a deux objectifs: réduire les accidents ischémiques et améliorer la qualité de vie du patient. Pourtant, la mesure de l’efficacité des traitements visant à améliorer la qualité de vie des patients repose généralement sur la simple évaluation du périmètre de marche. Depuis une vingtaine d’années, des outils de mesure de la qualité de vie ont été développés et l’impact de l’artériopathie sur la qualité de vie a pu être mesuré à l’aide de questionnaires généraux ou spécifiques comme le questionnaire ARTEMIS®. Les études ont permis de démontrer l’association globale entre qualité de vie et claudication intermittente: plus le périmètre de marche est faible, plus les répercussions sur la qualité de vie sont importantes en moyenne. Mais elles ont surtout révélé la grande dispersion des scores de qualité de vie pour des niveaux voisins de limitations fonctionnelles. La dispersion des scores est d’autant plus grande que la claudication est sévère. Ces résultats suggèrent que la prise en charge du malade atteint d’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs devrait tenir compte du score de qualité de vie, en particulier pour orienter les traitements fonctionnels vers les patients ayant des scores dégradés indépendamment de leur périmètre de marche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Références

Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barret-Connor E, et al. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation 1985; 71: 510–5

Chanu B, Rouffy J. Histoire naturelle. In: Rouffy J, Natali J, editors. Artériopathies athéromateuses des membres inférieurs. Ch. 6. Paris: Masson, 1988: 150–60

Leng GC, Fowkes FGR. Epidémiologie de la maladie vasculaire périphérique. Acta Med Int — Angiologie 1991; 136: 1752–61

Smith GD, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Intermittent claudication, heart disease risk factors, and mortality. Circulation 1990; 6: 1925–31

Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl JMed 1992; 326: 381–6

Schipper H, Clinch J, Powell V. Definitions and conceptual issues. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life assessments in clinical trials. New York: Raven Press, 1990; 2: 11–24

Leplege A, Mesbah M, Marquis P. Analyse préliminaire des propriétés psychométriques de la version française d’un questionnaire international de mesure de la qualité de vie: le MOS SF-36 (version 1.1). Rev Epidemiol Santé Publique 1995; 43: 371–9

Wilson A, Wiklund I, Lahti T, et al. A summary index for the assessment of quality of life in angina pectoris. J Clin Epidemiol 1991; 44: 981–8

Briançon S, Alla F, Méjat E, et al. Mesure de l’incapacité fonctionnelle et de la qualité de vie dans l’insuffisance cardiaque. Adaptation transculturelle et validation des questionnaires de Goldman, du Minesota et de Duke. Arch Mal Cœur Vaiss 1997; 90: 1577–85

Bousquet J, Bullinger M, Fayol C, et al. Assessment of quality of life in chronic allergic rhinitis using an enhanced version of the SF-36 questionnaire. J Allergy Immunol 1994; 94: 182–8

Marquis P, Fayol C, McCarthy C, et al. Mesure de la qualité de vie dans la claudication intermittente. Validation clinique d’un questionnaire. Presse Med 1994; 23: 1288–92

Marquis P. Généralités sur les outils de qualité de vie. Actualités vasculaires internationales. Présence et communication médicales. Neuilly sur Seine, 1994; hors série: 12-3

The European Group for Quality of Life and Health Measurement. European Guide to the Nottingham Health Profile. The European Group for Quality of Life and Health Measurement. Dauphin, 1992

Bucquet D. L’indicateur de santé perceptuelle de Nottingham comme exemple d’instrument de mesure de la “Qualité de Vie liée à la Santé”. Rev Méd Interne 1991; 12: 255–6

Chetter IC, Spark JI, Dolan P, et al. Quality of life analysis in patients with lower limb ischaemia: suggestions for European standardisation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997; 13: 597–604

Ware JE. Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, 1993

Berger M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, et al. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981; 19(8): 787–805

Chwalow AJ, Lurie A, Bean K, et al. A French version of the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP): stages in the cross-cultural validation of a generic quality of life scale. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1992; 6: 319–26

Parkerson GR, Broadhead WE, Tse CK. The Duke Health Profile: a 17-item measure of health and dysfunction. Med Care 1990; 28(11): 1056–70

Guillermin F, Paul-Dauphin A, Virion JM, et al. The Duke Health Profile: cross cultural adaptation and validation of a generic quality of life measure. Qual Life Res 1995; 4(5): 436

Erickson P, Scott J. The on-line guide to quality-of-life assessment (OLGA): resource for selecting quality-of-life assessments. In: Walker S, Rosser RM, editors. Quality-of-life assessment: key issues in the 1990s. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993; 13: 221–32

Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD. Self administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med 1977; 31: 42

Ponte E, Cattinelli S. Quality of life in a group of patients with intermittent claudication. Angiology 1996; 47: 247–51

Chambers LW The McMaster Health Index Questionnaire (MHIQ): methodologic documentation and report of second generation of investigations. Hamilton, Ontario: Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, 1982

Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 1979; 9: 139–45

Barletta G, Perna S, Sabba C, et al. Quality of life in patients with intermittent claudication — relationship with laboratory exercise performance. Vasc Med 1996; 1: 3–7

Ware JE, Sherbourne CA. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–83

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcomes measure for primary care. BMJ 1992; 305: 160–4

Martin C, Ware JE, Marquis P. Quality of life in duodenal ulcer patients: development and validation of a specific questionnaire. Gastroenterology 1991; 100 (5 Pt 12): A12

Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, et al. International quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Qual Life Res 1992; 1: 349–51

Ware J, Gandek B, Keller SD, et al. Evaluating instruments used cross-nationally: methods from the IQOLA project. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Press, 1996: 337–46

Sherbourne CD. Pain measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992: 220–35

Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. Health perceptions, energy/ fatigue, and health distress measures in measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992; 8: 143–72

Berki SE, Ashcraft ML. On the analysis of ambulatory utilization. Med Care 1979; 17: 1163–81

Creutzig A, Bullinger M, Cachovan M, et al. Improvement in the quality of life after IV PGE1 therapy for intermittent claudication. Vasa 1997; 26: 122–7

Spengel FA, Brown TM, Dietze S, et al. The Claudication Scale (Clau-S): a new disease-specific quality of life instrument in intermittent claudication. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 1997; 2(1): 65–70

Liard F, Benichou AC, Gamand S, et al. The effects of naftidrofuryl on quality of life. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 1997; 2(1): 71–8

Meilhac B, Montestruc F, Aubin F, et al. Etude comparative randomisée en double aveugle de la nicergoline et du naftidrofuryl sur la qualité de vie dans l’artériopathie chronique oblitérante des membres inférieurs au stade de la claudication intermittente. Thérapie 1997; 52: 179–86

Fratezi A, Albers M, De Luccia N, et al. Outcome and quality of life of patients with severe chronic limb ischaemia: a cohort study on the influence of diabetes. Eur J Vasc Surg 1995; 10: 459–65

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marquis, P. Evaluation de l’impact de l’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs sur la qualité de vie. Drugs 56 (Suppl 3), 25–35 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199856003-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199856003-00004