Abstract

Background

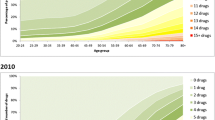

The prevalence of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in a geriatric population may be high because of polypharmacy. However, wide variance in the clinical relevance of these interactions has been shown.

Objectives

To explore whether adverse drug reactions (ADRs) as a result of DDIs can be identified by clinical evaluation, to describe the prevalence of ADRs and diminished drug effectiveness as a result of DDIs and to verify whether the top ten most frequent potential DDIs known to public pharmacies are of primary importance in geriatric outpatients in the Netherlands.

Method

All adverse events classified by the Naranjo algorithm as being a possible ADR and drug combinations resulting in diminished drug effectiveness were identified prospectively in 807 geriatric outpatients (mean age 81 years) at their first visit. The setting was a diagnostic day clinic. The Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) and Beers criteria were used to evaluate drug use and identify possible DDIs. The ten most frequent potential interactions, according to a 1997 national database of public pharmacies (‘Top Ten’) in the Netherlands, and possible adverse events as a result of other interactions, were described. The effects of changes in medication regimen were recorded by checking the medical records.

Results

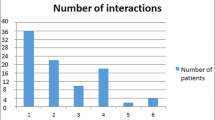

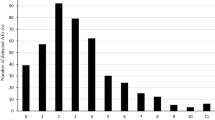

In 300 patients (44.5% of the 674 patients taking more than one drug), 398 potential DDIs were identified. In 172 (25.5%) of patients taking more than one drug, drug combinations were identified that were responsible for at least one ADR or which possibly resulted in reduced effectiveness of therapy. Eighty-four of the 158 possible ADRs resulting from enhanced action of drugs forming combinations listed in the ‘Top Ten’ were seen in 73 patients. Only four DDIs resulting in less effective therapy that involved drug combinations in the ‘Top Ten’ were identified. Changes in drug regimens pertaining to possible interactions were proposed or put into effect in 111 of the 172 (65%) patients with possible DDIs. Sixty-one (55%) of these patients returned for follow-up. Of these, 49 (80%) were shown to have improved after changes were made to their medication regimen.

Conclusion

In this study, nearly half of the geriatric outpatients attending a diagnostic day clinic who were taking more than one drug were candidates for DDIs. One-quarter of these patients were found to have possible adverse events or diminished treatment effectiveness that may have been at least partly caused by these DDIs. These potential interactions can be identified through clinical evaluation. In the majority of patients (99 of 172) the potential interactions resulting in possible ADRs or diminished effectiveness were not present in the ‘Top Ten’ interactions described by a national database of public pharmacies, a finding that emphasizes that the particular characteristics of geriatric patients (e.g. frequent psychiatric co-morbidities) need to be considered when evaluating their drug use. At least 7% of all patients taking more than one drug, and 80% of those with possible drug interactions whose drug regimen was adjusted, benefited from changes made to their drug regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rollason V, Vogt N. Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly. A systematic review of the role of the pharmacist. Drugs Aging 2003; 20: 817–32

Heerdink ER. Polypharmacy in the elderly in the Netherlands, an overview of available data [in Dutch]. Pharm Weekbl 2002; 137: 1257–9

van der Hooft CS, Sturkenboom MCJM, van Grootheest K, et al. Adverse drug reaction-related hospitalizations: a nationwide study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2006; 29(2): 161–8

Mannesse CK, Derkx FH, de Ridder MA, et al. Adverse drug reactions as contributing factor for hospital admission: cross sectional study. BMJ 1997; 315: 1057–8

Köhler GI, Bode-Böger SM, Bgusse R, et al. Drug-drug interactions in medical patients: effects of in-hospital treatment and relation to multiple drug use. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000; 38: 504–13

Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, et al. Adverse drug reactions as a cause of hospital admissions: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA). J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1962–8

Jansen PAF. Clinically relevant drug interactions in the elderly [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003 Mar 29; 147(13): 595–9

Zhan C, Correa-de-Araujo R, Bierman AS, et al. Suboptimal prescribing in elderly outpatients: potentially harmful drug-drug and drug-disease combinations. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 262–7

Schmader K, Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, et al. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 1241–7

Doucet J, Chassagne P, Trivalle C. Drag-drug interactions related to hospital admissions in older adults: a prospective study of 1000 patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44: 944–8

Seymour RM, Routledge PA. Important drug-drag interactions in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1998; 12: 485–94

Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colcone A, et al. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38: 666–71

Glintborg B, Andersen SE, Dalhoff K. Drug-drug interactions among recently hospitalised patients — frequent but mostly clinically insignificant. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61(9): 675–81

Bjorkmann IK, Fasrbom J, Schnidt IK, et al. Drug-drag interactions in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36(11): 1675–81

Bonetti PO, Hartmann K, Kuhn M, et al. Potentielle arzneimittelinteraktionen und Verordnungshäufigkeit von medikamenten mit speziellen instruktionsbedarf bei spittalaustritt. Praxis 2000; 89: 182–9

Heininger-Rothbucher D, Bischinger S, Ulmer H, et al. Incidence and risk of potential adverse drag interactions in the emergency room. Resuscitation 2001; 49: 283–8

Egger T, Dormann H, Ahne G, et al. Identification of adverse drug reactions in geriatric inpatients using a computerised drag database. Drags Aging 2003; 20(10): 769–76

Saltvedt I, Spigset O, Ruths S, et al. Patterns of drag prescription in a geriatric evaluation and management unit as compared with the general medical wards: a randomised study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 921–8

Chen YF, Avery AJ, Neil KE, et al. Incidence and possible causes of prescribing potentially hazardous/contraindicated drug combinations in general practice. Drag Saf 2005; 28(1): 67–80

Straubhaar B, Kranenbuhl S, Schlienger RG. The prevalence of potential drag-drug interactions in patients with heart failure at hospital discharge. Drag Saf 2006; 29(1): 79–90

Peng CC, Glassman PA, Marks IR, et al. Retrospective drag utilization review: incidence of clinically relevant potential drug-drug interactions in a large ambulatory population. J Manag Care Pharm 2003; 9(6): 513–22

Schalekamp T. Dealing with drug-drug interactions [in Dutch]. Gebu 1997; 31: 87–94

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12: 189–98

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KA, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies. J Chron Dis 1987; 40(5): 373–83

Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE. A summated score for the Medication Appropriateness Index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47: 891–6

Busto U, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Comparison of two recently published algorithms for assessing the probability of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 13(2): 223–73

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 2716–24

Dalton SO, Johansen C, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(1): 59–64

Buurma H, De Smet PAGM, Egberts ACG. Clinical risk management in Dutch community pharmacies: the case of drag-drug interactions. Drag Saf 2006; 29(8): 723–32

van Roon EN, Flikweert S, le Comte M, et al. Clinical relevance of drug-drug interactions: a structured assessment procedure. Drug Saf 2005; 28(12): 1131–9

van der Linden CMJ, Kerskes MCH, Bijl AM, et al. Represcription after adverse drag reaction in the elderly: a descriptive study. Arch Intern Med 2006; 28: 1666–7

Weingart SN, Toth M, Sands DZ, et al. Physicians’ decisions to override computerized drug alerts in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(21): 2625–31

Malone DC, Hutchins DS, Haupert H, et al. Assessment of potential drug-drug interactions with a prescription claims database. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2005; 62(19): 1983–91

Howard PA, Ellerbeck EF, Engelman JJ, et al. The nature and frequency of potential warfarin drug interactions that increase the risk of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacoepidemiol Drag Saf 2002; 11(7): 569–76

Gurwitz JH, Fields TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drag events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003; 289: 1107–16

Jabaaij L. Medication in the elderly: what and for what? [in Dutch]. Huisarts en Wetenschap 2003; 46(2): 69

Veehof LJ, Stewart R, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, et al. Chronic polypharmacy in one-third of the elderly in family practice [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1999; 143(2): 93–7

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tulner, L.R., Frankfort, S.V., Gijsen, G.J.P.T. et al. Drug-Drug Interactions in a Geriatric Outpatient Cohort. Drugs Aging 25, 343–355 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825040-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825040-00007