Abstract

Synopsis

Pamidronate (APD) is a potent inhibitor of bone resorption that is useful in the management of patients with osteolytic bone metastases from breast cancer or multiple myeloma, tumour- induced hypercalcaemia or Paget’s disease of bone. After intravenous administration, the drug is extensively taken up in bone, where it binds with hydroxyapatite crystals in the bone matrix. Matrix- boundpamidronate inhibits osteoclast activity by a variety of mechanisms, the most important of which appears to be prevention of the attachment of osteoclast precursor cells to bone.

In patients with osteolytic bone metastases associated with either breast cancer or multiple myeloma, administration of pamidronate together with systemic antitumour therapy reduces and delays skeletal events, including pathological fracture, hypercalcaemia and the requirement for radiation treatment or surgery to bone. Pamidronate generally improves pain control. Quality- of- life and performance status scores in pamidronate recipients were generally as good as, or better than, those in patients who did not receive the drug. Overall survival does not appear to be affected by pamidronate therapy.

Tumour-induced hypercalcaemia also responds well to pamidronate therapy: 70 to 100% of patients achieve normocalcaemia, generally 3 to 5 days after treatment. Response durations vary, but are commonly 3 weeks or longer. In comparative studies, pamidronate produced higher rates of normocalcaemia and longer normocalcaemic durations than other available osteoclast inhibitors, including intravenous etidronate, clodronate and plicamycin (mithramycin).

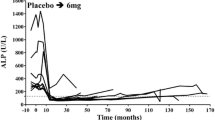

In most patients with Paget’s disease of bone, intravenous pamidronate reduces bone pain and produces biochemical response. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels generally fall 50 to 70% from baseline 3 to 4 months after pamidronate treatment. Biochemical response may be prolonged.

Pamidronate is well tolerated by most patients. Transient febrile reactions, sometimes accompanied by myalgias and lymphopenia, occur commonly after the first infusion of pamidronate. Other reported adverse events include transient neutropenia, mild thrombophlebitis, asymptomatic hypocalcaemia and, rarely, ocular complications (uveitis and scleritis).

Pamidronate should be considered for routine use together with systemic hormonal or cytotoxic therapy in patients with breast cancer or multiple myeloma and osteolytic metastases. At present, pamidronate is the drug of choice for first- line use in the management of patients with tumour- induced hypercalcaemia. It is an effective treatment for Paget’s disease and is the treatment of choice where oral bisphosphonates are not an option.

Pharmacology

Pamidronate (APD) is an inhibitor of bone resorption that, unlike etidronate, does not appear to impair bone mineralisation at therapeutic dosages in patients with Paget’s disease. Pamidronate inhibits osteoclast activity primarily by binding with hydroxyapatite crystals in the bone matrix, preventing the attachment of osteoclast precursor cells. Other mechanisms of action of matrix-bound pamidronate may include direct inhibition of mature osteoclast function, promotion of osteoclast apoptosis and interference with osteoblast-mediated osteoclast activation.

The initial plasma half-life of the drug is <1 hour (for a 1- to 24-hour infusion). 31 to 41% of an intravenous dose of 60mg is recovered in the urine within 24 hours of administration. Most of the remaining drug is taken up by bone, from where it is eliminated very slowly. The terminal half-life is many months. Body retention after an intravenous dose correlated with the number of metastases in patients with cancer. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve was increased in patients with severe renal dysfunction.

Therapeutic Use

Osteolytic bone metastases. Administered in conjunction with systemic antitumour therapy in patients with breast cancer or Durie-Salmon stage III multiple myeloma and at least 1 bone lesion, Pamidronate reduced the overall incidence and delayed the onset of skeletal complications (pathological fracture, hypercalcaemia, or radiation treatment or surgery to bone). Pamidronate also prolonged the time to progressive disease in bone in patients with breast cancer. In patients with breast cancer and in those with myeloma, pamidronate recipients had better pain control than patients who did not receive the drug. Quality-of-life and performance status scores of pamidronate recipients were the same as, or better than, those in patients who did not receive the drug. Pamidronate did not affect overall survival in these 2 year studies.

Tumour-induced hypercalcaemia. 70 to 100% of patients with hypercalcaemia of malignancy achieve normocalcaemia after pamidronate therapy. Elevated calcium levels begin to fall within 24 to 48 hours after administration of the drug and normocalcaemia is typically achieved after 3 to 5 days. The duration of normocalcaemia is variable, but many patients achieve remissions of ≥3 weeks. Pamidronate appears to be more effective than other available osteoclast inhibitors in patients with hypercalcaemia. More patients achieved normocalcaemia, and the duration of this response was longer, after treatment with pamidronate than after treatment with etidronate, clodronate or plicamycin (mithramycin).

Paget’s disease of bone. Pamidronate reduces bone pain, serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels and urinary hydroxyproline to creatinine ratios in most patients. Duration of biochemical response did not appear to correlate with the administered dose, but did correlate with both pretreatment biochemical disease severity and the percentage decrease in ALP levels 6 weeks after treatment. Response durations may be long.

Tolerability

Pamidronate is very well tolerated. Within 5 days of their first infusion, 60 to 75% of patients experience a transient febrile response (v0.5°C elevation in body temperature) that lasts ≤24 hours. This acute-phase reaction, which may be accompanied by myalgias and lymphopenia, is normally responsive to paracetamol (acetaminophen). Nonfebrile patients may also develop transient lymphopenia.

Mild thrombophlebitis at the injection site and transient, asymptomatic hypocalcaemia and transient neutropenia have also been reported after pamidronate. A small proportion of patients (≤ 1%) experience reversible ocular complications, principally uveitis and scleritis reactions.

Dosage and Administration

Pamidronate is administered by intravenous infusion. Patients with stage III multiple myeloma or breast cancer and at least 1 osteolytic bone lesion should receive pamidronate 90mg monthly together with systemic antitumour treatment. The optimum duration of pamidronate therapy is not yet defined. However, in large, randomised trials, patients with breast cancer or multiple myeloma, respectively, received 24 and 21 monthly cycles of pamidronate.

For patients with moderate tumour-induced hypercalcaemia [adjusted serum calcium 2.99 to 3.37 mmol/L (12.0 to 13.5 mg/dl)], the recommended dose of pamidronate is a single 60 to 90mg infusion. In severe hypercalcaemia [>3.37 mmol/L (13.5 mg/dl)], pamidronate 90mg should be administered.

In patients with Paget’s disease, the optimum pamidronate dosage is not known. Recommended regimens include pamidronate 30mg daily for 3 days (US) and 180 to 210mg administered in divided doses over 6 weeks (UK). Dosage regimens based on initial biochemical disease severity may also be appropriate.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

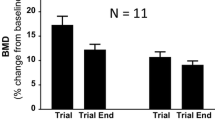

Reid IR, Wattie DJ, Evans MC, et al. Continuous therapy with pamidronate, a potent bisphosphonate, in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994 Dec; 79: 1595–9

Orr-Walker B, Wattie DJ, Evans MC, et al. Effects of prolonged bisphosphonate therapy and its discontinuation on bone mineral density in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Clin Endocrinol 1997 Jan; 46: 87–92

Clarke NW, Holbrook IB, McClure J, et al. Osteoclast inhibition by pamidronate in metastatic prostate cancer: a preliminary study. Br J Cancer 1991 Mar; 63: 420–3

Masud T, Slevin ML. Pamidronate to reduce bone pain in normocalcaemic patient with disseminated prostatic carcinoma [letter]. Lancet 1989 May 6; I: 1021–2

Pelger RCM, Nijeholt A, Papapoulos SE. Short-term metabolic effects of pamidronate in patients with prostatic carcinoma and bone metastases. Lancet 1989 Oct 7; II: 865

Berruti A, Sperone P, Cerutti S, et al. Pamidronate administration to bone metastatic patients from prostate cancer (PC) improves bone metabolic derangement and bone pain [abstract no. 206]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 59a

Limouris GS, Manetou A, Moulopoulou A, et al. Evaluation of a combined radionuclide therapy for the treatment of mixed bony metastases [abstract no. 118]. J Nucl Med 1996; 37(5): 32P

Dodwell DJ. Malignant bone resorption: cellular and biochemical mechanisms. Ann Oncol 1992; 3: 257–67

Hosking DJ. Advances in the management of Paget’s disease of bone. Drugs 1990 Dec; 40: 829–40

Averbuch SD. New bisphosphonates in the treatment of bone metastases. Cancer 1993; 72 Suppl.: 3443–52

Fitton A, McTavish D. Pamidronate: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in resorptive bone disease. Drugs 1991 Feb; 41: 289–318

Body JJ, Coleman RE, Piccart M. Use of bisphosphonates in cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev 1996 Jul; 22: 265–87

Boonekamp PM, van der Wee-Pals LJA, van Wijk-van Lennep MML, et al. Two modes of action of bisphosphonates on osteoclastic resorption of mineralized matrix. Bone Miner 1986; 1: 27–39

Evans CE, Braidman IP. Effects of two novel bisphosphonates on bone cells in vitro. Bone Miner 1994 Aug; 26: 95–107

Sahni M, Guenther HL, Fleisch H, et al. Bisphosphonates act on rat bone resorption through the mediation of osteoblasts. J Clin Invest 1993; 91: 2004–11

Hughes DE, Wright KR, Uy HL, et al. Bisphosphonates promote apoptosis in murine osteoclasts in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 1995 Oct; 10: 1478–87

Fenton AJ, Gutteridge DH, Kent GN, et al. Intravenous aminobisphosphonate on Paget’s disease: clinical, biochemical, histomorphometric and radiological responses. Clin Endocrinol 1991; 34: 197–204

Adamson BB, Gallacher SJ, Byars J, et al. Mineralisation defects with pamidronate therapy for Paget’s disease. Lancet 1993 Dec 11; 342: 1459–60

Liens D, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Long-term effects of intravenous pamidronate in fibrous dysplasia of bone. Lancet 1994 Apr 16; 343: 953–4

van der Pluijm G, Vloedgraven H, van Beek E, et al. Bisphosphonates inhibit the adhesion of breast cancer cells to bone matrices in vitro. J Clin Invest 1996 Aug 1; 98: 698–705

Coleman R, Vinholes J, Purohit O, et al. Effects of pamidronate on tumour marker levels in breast and prostate cancer — correlation with clinical and biochemical response [abstract no. 1179]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 330a

Thürlimann B, Köberle D, Engler H, et al. Predictive factors for response to bisphosphonate treatment in malignant osteolytic bone disease: who will respond to pamidronate? [abstract no. 181]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 52a

Gallacher SJ, Fraser WD, Logue FC, et al. Factors predicting the acute effect of pamidronate on serum calcium in hypercalcemia of malignancy. Calcif Tissue Int 1992 Dec; 51: 419–23

Body JJ, Dumon JC, Thirion M, et al. Circulating PTHrP concentrations in tumor-induced hypercalcemia: influence on the response to bisphosphonate and changes after therapy. J Bone Miner Res 1993 Jun; 8: 701–6

Leyvraz S, Hess U, Flesch G, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pamidronate in patients with bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992 May 20; 84: 788–92

Daley-Yates PT, Dodwell DJ, Pongchaidecha M, et al. The clearance and bioavailability of pamidronate in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases. Calcif Tissue Int 1991 Dec; 49: 433–5

Dodwell DJ, Howell A, Morton AR, et al. Infusion rate and pharmacokinetics of intravenous pamidronate in the treatment of tumour-induced hypercalcaemia. Postgrad Med J 1992 Jun; 68: 434–9

Redalieu E, Coleman JM, Chan K, et al. Urinary excretion of aminohydroxypropylidene bisphosphonate in cancer patients after single intravenous infusions. J Pharm Sci 1993 Jun; 82: 665–7

Berenson JR, Rosen L, Vescio R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pamidronate disodium in patients with cancer with normal or impaired renal function. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37: 285–90

Glover D, Lipton A, Keller A, et al. Intravenous pamidronate disodium treatment of bone metastases in patients with breast cancer: a dose-seeking study. Cancer 1994 Dec 1; 74: 2949–55

Radziwill AJ, Thurlimann B, Jungi WF. Improvement of palliation in patients with osteolytic bone disease and unsatisfactory pain control after pretreatment with disodium pamidronate: an intra-patient dose escalation study. Onkologie 1993; 16(3): 174–7

Purohit OP, Anthony C, Radstone CR, et al. High-dose intravenous pamidronate for metastatic bone pain. Br J Cancer 1994 Sep; 70: 554–8

Thürlimann B, Morant R, Jungi WF, et al. Pamidronate for pain control in patients with malignant osteolytic bone disease: a prospective dose-effect study. Support Care Cancer 1994 Jan; 2: 61–5

Coleman RE, Purohit OP, Vinholes J, et al. A randomised double-blind trial of pamidronate for metastatic bone pain [abstract]. Br J Cancer 1996 Mar; 73Suppl. XXVI: 55

Köberle D, Thürlimann B, Engler H, et al. Double blind intravenous pamidronate (APD) 60 mg versus 90 mg in patients with malignant osteolytic bone disease and pain [abstract no. 182]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 53a

Conte PF, Latreille J, Mauriac L, et al. Delay in progression of bone metastases in breast cancer patients treated with intravenous pamidronate: results from a multinational randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 1996 Sep; 14: 2552–9

Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and lytic bone metastases. N Engl J Med 1996 Dec 12; 335: 1785–91

Lipton A, Theriault R, Leff R, et al. Reduction of skeletal related complications in breast cancer patients with osteolytic bone metastases receiving hormone therapy, by monthly pamidronate sodium (Aredia®) infusion [abstract]. Br J Cancer 1996 Jul; 74Suppl. 28: 11

Hultborn R, Gundersen S, Rydén S, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in breast cancer with bone metastases: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled multicenter study. Acta Oncol 1996; 35Suppl. 5: 73–4

Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 1996 Feb 22; 334: 488–93

Hortobagyi GN, Porter L, Theriault RL, et al. Long-term reduction of skeletal complications in breast cancer patients (pts) with osteolytic bone metastases receiving chemotherapy, by monthly 90 mg pamidronate (Aredia®) infusions [abstract no. 530]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 151a

Lipton A, Hershey PA, Theriault R, et al. Long-term reduction of skeletal complications in breast cancer patients (pts) with osteolytic bone metastases receiving hormone therapy, by monthly 90 mg pamidronate (Aredia®) infusions [abstract no. 531]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997; 16: 152a

Lipton A. Bisphosphonates and breast carcinoma. Cancer 1997; 80 Suppl.: 1668–73

Lipton A, Theriault RL, Hortobagyi GN, et al. Long-term treatment with pamidronate reduces skeletal morbidity in women receiving endocrine treatment for advanced breast cancer and lytic bone lesions. Novartis Pharma AG (Basel), 1997 Oct 11: 1–26 (Data on file)

Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Lipton A, et al. Long-term prevention of skeletal complications of metastatic breast cancer with pamidronate. Novartis Pharma AG (Basel), 1997: 1–25 (Data on file)

Berenson JR. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Cancer 1997; 80 Suppl.: 1661–7

Berenson JR. The efficacy of pamidronate disodium in the treatment of osteolytic lesions and bone pain in multiple myeloma. Novartis Pharma AG (Basel), 1997: 1–32 (Data on file)

Ciba Aredia shows six-month difference in median time to first skeletal event in breast cancer patients; FDA Committee recommends breast cancer use. FDC Pink Sheet 1996 Jun 17; 58: 7–8

Aredia OK’d for bone metastases in US. Scrip 1996 Jun 21 (2139): 22

Mannix KA, Carmichael J, Harris AL, et al. Single high-dose (45 mg) infusions of aminohydroxypropylidene diphosphonate for severe malignant hypercalcemia. Cancer 1989 Sep 15; 64: 1358–61

Wimalawansa SJ. Significance of plasma PTH-rp in patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy treated with bisphosphonate. Cancer 1994 Apr 15; 73: 2223–30

Body JJ, Borkowski A, Cleeren A, et al. Treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia with intravenous aminohydroxy-propylidene diphosphonate. J Clin Oncol 1986 Aug; 4: 1177–83

Grutters JC, Hermus ARMM, de Mulder PHM, et al. Long-term follow up of breast cancer patients treated for hypercalcaemia with aminohydroxypropylidene bisphosphonate (APD). Breast Cancer Res Treat 1993; 25(3): 277–81

Morton AR, Cantrill JA, Pillai GV, et al. Sclerosis of lytic bone metastases after disodium aminohydroxypropylidene bisphosphonate (APD) in patients with breast carcinoma. BMJ 1988 Sep 24; 297: 772–3

Gucalp R, Ritch P, Wiernik PH, et al. Comparative study of pamidronate disodium and etidronate disodium in the treatment of cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Clin Oncol 1992 Jan; 10: 132–42

Østenstad B, Andersen OK. Disodium pamidronate versus mithramycin in the management of tumour-associated hypercalcemia. Acta Oncol 1992; 31: 861–4

Purohit OP, Radstone CR, Anthony C. A randomised doubleblind comparison of intravenous pamidronate and clodronate in the hypercalcaemia of malignancy. Br J Cancer 1995 Nov; 72: 1289–93

Thürlimann B, Waldburger R, Senn HJ, et al. Plicamycin and pamidronate in symptomatic tumor-related hypercalcemia: a prospective randomized crossover trial. Ann Oncol 1992 Aug; 3: 619–23

Vinholes J, Guo C-Y, Purohit OP, et al. Evaluation of new bone resorption markers in a randomized comparison of pamidronate or clodronate for hypercalcemia of malignancy. J Clin O ncol 1997 Jan; 15: 131–8

Neskovi-Konstantinovi Z, Mitrovi L, Petrovi J, et al. Treatment of tumour-induced hypercalcaemia in advanced breast cancer patients with three different doses of disodium pamidronate adapted to the initial level of calcaemia. Support Care Cancer 1995 Nov; 3: 422–4

Morton AR, Cantrill JA, Craig AE, et al. Single dose versus daily intravenous aminohydroxypropylidene biphosphonate (APD) for the hypercalcaemia of malignancy. Br Med J Clin Res Ed 1988 Mar 19; 296: 811–4

Gallacher SJ, Ralston SH, Fraser WD, et al. A comparison of low versus high dose pamidronate in cancer-associated hypercalcaemia. Bone Miner 1991 Dec; 15: 249–56

Nussbaum SR, Younger J, VandePol CJ, et al. Single-dose intravenous therapy with pamidronate for the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: comparison of 30-, 60-, and 90-mg dosages. Am J Med 1993 Sep; 95: 297–304

Body JJ, Dumon JC. Treatment of tumour-induced hypercalcaemia with the bisphosphonate pamidronate: dose-response relationship and influence of tumour type. Ann Oncol 1994 Apr; 5: 359–63

Walls J, Ratcliffe WA, Howell A, et al. Response to intravenous bisphosphonate therapy in hypercalcaemic patients with and without bone metastases: the role of parathyroid hormonerelated protein. Br J Cancer 1994 Jul; 70: 169–72

Pecherstorfer M, Thiébaud D. Treatment of resistant tumorinduced hypercalcemia with escalating doses of pamidronate. Ann Oncol 1992 Aug; 3: 661–3

Wimalawansa SJ. Optimal frequency of administration of pamidronate in patients with hypercalcaemia of malignancy. Clin Endocrinol 1994 Nov; 41: 591–5

Ralston SH, Gallacher SJ, Patel U, et al. Comparison of three intravenous bisphosphonates in cancer-associated hypercalcaemia. Lancet 1989; II: 1180–2

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Paterson AHG. Use of diphosphonates in hypercalcaemia due to malignancy [letter]. Lancet 1990; 335: 170–1

Ralston SH, Gardner MD, Dryburgh FJ, et al. Comparison of aminohydroxypropylidene diphosphonate, mithramycin, and corticosteroids/calcitonin in treatment of cancer-associated hypercalcaemia. Lancet 1985 Oct 26; II: 907–10

Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. The management of Paget’s disease of bone. N Engl J Med 1997 Feb 20; 336: 558–66

Meunier PJ, Vignot E. Therapeutic strategy in Paget’s disease of bone. Bone 1995 Nov; 17 (5 Suppl): 489S–91S

Fraser TRC, Ibbertson HK, Holdaway IM, et al. Effective oral treatment of severe Paget’s disease of bone with APD (3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene-1, 1-bisphosphonate): a comparison with combined calcitonin + EHDP (1-hydroxyethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate). Aust N Z J Med 1984; 14: 811–8

Gutteridge DH, Retallack RW, Ward LC, et al. Clinical, biochemical, hematologic, and radiographic responses in Paget’s disease following intravenous pamidronate disodium: a 2-year study. Bone 1996; 19(4): 387–94

Bombassei GJ, Yocono M, Raisz LG. Effects of intravenous pamidronate therapy on Paget’s disease of bone. Am J Med Sci 1994 Oct; 308: 226–33

Cantrill JA, Buckler HM, Anderson DC. Low dose intravenous 3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate (APD) for the treatment of Paget’s disease of the bone. Ann Rheum Dis 1986; 45: 1012–8

Chakravarty K, Merry P, Scott DGI. A single infusion of bisphosphonate AHPrBP in the treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. J Rheumatol 1994 Nov; 21: 2118–21

Gallacher SJ, Boyce BF, Patel U, et al. Clinical experience with pamidronate in the treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. Ann Rheum Dis 1991 Dec; 50: 930–3

Harinck HI, Papapoulos SE, Blanksma HJ, et al. Paget’s disease of bone: early and late responses to three different modes of treatment with aminohydroxypropylidene bisphosphonate (APD). Br Med J Clin Res Ed 1987 Nov 21; 295: 1301–5

Patel S, Stone MD, Coupland C, et al. Determinants of remission of Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 1993 Dec; 8: 1467–73

Pepersack T, Karmali R, Gillet C, et al. Paget’s disease of bone: five regimens of pamidronate treatment. Clin Rheumatol 1994 Mar; 13: 39–44

Ryan PJ, Sherry M, Gibson T, et al. Treatment of Paget’s disease by weekly infusions of 3-aminohydroxypropylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate (APD). Br J Rheumatol 1992 Feb; 31: 97–101

Thiébaud D, Jaeger P, Gobelet C, et al. A single infusion of the bisphosphonate AHPrBP (APD) as treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. Am J Med 1988; 85: 207–12

Thiebaud D, Portmann L, Burckhardt P. Moderate Paget’s disease treated with pamidronate: comparison of various infusion rates for a 60-mg single dose. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1994 Feb; 23: 279

Watts RA, Skingle SJ, Bhambhani MM, et al. Treatment of Paget’s disease of bone with single dose intravenous pamidronate. Ann Rheum Dis 1993 Aug; 52: 616–8

Wimalawansa SJ, Gunasekera RD. Pamidronate is effective for Paget’s disease of bone refractory to conventional therapy. Calcif Tissue Int 1993 Oct; 53: 237–41

Stone MD, Hawthorne AB, Kerr D, et al. Treatment of Paget’s disease with intermittent low-dose infusions of disodium pamidronate. J Bone Miner Res 1990 Dec; 5: 1231–5

Ismail AA, Fox P, Stamp TCB, et al. Treatment of Paget’s disease of bone with intravenous pamidronate: comparison of 2 different modes of treatment [letter]. J Rheumatol 1997; 24(11): 2266–7

Ismail AA, Fox P, Godlstein AJ, et al. Treatment of Pagets disease with I–V pamidronate (APD) — four year follow up [abstract]. Br J Rheumatol 1994; 33Suppl. 2: 33

Le Goff P, Saraux A, Valls-Bellec I, et al. Treatment of Paget’s disease with pamidronate: usefulness of repeated infusions [abstract no. J91]. Rev Rhum English Ed 1996; 63: 760

Yap AS, Mortimer RH, Jacobi JM, et al. Single-dose intravenous pamidronate is effective alternative therapy for Paget’s disease refractory to calcitonin. Horm Res 1991; 36(1–2): 70–4

Cundy T, Wattie D, King AR. High-dose pamidronate in the management of resistant Paget’s disease. Calcif Tissue Int 1996 Jan; 58: 6–8

Ryan PJ, Gibson T, Fogelman I. Bone scintigraphy following intravenous pamidronate for Paget’s disease of bone. J Nucl Med 1992 Sep; 33: 1589–93

Johansen A, Stone M, Rawlinson F. Bisphosphonates and the treatment of bone disease in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1996 Feb; 8: 113–26

Buckler HM, Mercer SJ, Davison CE, et al. Does an initial test dose of pamidronate minimise transient side effects in Paget’s disease of bone? [abstract]. Bone 1995 Jan; 16 Suppl.: 212S

Mautalen CA, Casco CA, Gonzalez D, et al. Side effects of disodium aminohydroxypropylidene diphosphonate (APD) during treatment of bone diseases. BMJ 1984; 288: 828–9

Macarol V, Fraunfelder FT. Pamidronate disodium and possible ocular adverse drug reactions. Am J Ophthalmol 1994 Aug 15; 118: 220–4

Des Grottes JM, Schrooyen M, Dumon JC, et al. Retrobulbar optic neuritis after pamidronate administration in a patient with a history of cutaneous porphyria. Clin Rheumatol 1997 Jan; 16: 93–5

Stewart GO, Stuckey BGA, Ward LC, et al. Iritis following intravenous pamidronate. Aust N Z J Med 1996 Jun; 26: 414–5

Machado CE, Flombaum CD. Safety of pamidronate in patients with renal failure and hypercalcemia. Clin Nephrol 1996 Mar; 45: 175–9

Watters J, Gerrard G, Dodwell D. The management of malignant hypercalcaemia. Drugs 1996 Dec; 52: 837–48

Ciba-Geigy Corporation. Aredia®: pamidronate disodium for injection [prescribing information]. Summit (NJ), USA: Ciba-Geigy Corporation; 1996. C96-51 (rev. 8/96)

Disodium pamidronate. British national formulary. 34th ed. London: British Medical Association, 1997 Sep: 331

Mercadante S. Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain 1997 Jan; 69: 1–18

Houston SJ, Rubens RD. The systemic treatment of bone metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995; 312: 95–104

Kanis JA. Bone and cancer: pathophysiology and treatment of metastases. Bone 1995 Aug; 17 Suppl.: 101–5

Belch AR, Bergsagel DE, Wilson K, et al. Effect of daily etidronate on the osteolysis of multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 1397–402

Lahtinen R, Laakso M, Palva I, et al. Randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Lancet 1992; 340: 1049–52

Paterson AHG, Powles TJ, Kanis JA, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of oral clodronate in patients with bone metastases from breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 59–65

Kovacs CS, MacDonald SM, Chik CL, et al. Hypercalcemia of malignancy in the palliative care patient: a treatment strategy. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995 Apr; 10: 224–32

Bilezikian JP. Management of acute hypercalcemia. N Engl J Med 1992 Apr 30; 326: 1196–203

Clissold SP, Fitton A, Chrisp P. Intranasal salmon calcitonin: a review of its pharmacological properties and potential utility in metabolic bone disorders associated with aging. Drugs Aging 1991 Sep–Oct; 1: 405–23

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coukell, A.J., Markham, A. Pamidronate. Drugs & Aging 12, 149–168 (1998). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199812020-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199812020-00007