Abstract

Background: The roll out of various public health programmes involving mass administration of medicines calls for the deployment of responsive pharmacovigilance systems to permit identification of signals of rare or even common adverse reactions. In developing countries in Africa, these systems are mostly absent and their performance under any circumstance is difficult to predict given the known shortage of human, financial and technical resources. Nevertheless, the importance of such systems in all countries is not in doubt, and research to identify problems, with the aim of offering pragmatic solutions, is urgently needed.

Objective: To examine the impact of training and monitoring of healthcare workers, making supervisory visits and the availability of telecommunication and transport facilities on the implementation of a pharmacovigilance system in Mozambique.

Methods: This was a descriptive study enumerating the lessons learnt and challenges faced in implementing a spontaneous reporting system in two rural districts of Mozambique — Namaacha and Matutuine — where remote location, poor telecommunication services and a low level of education of health professionals are ongoing challenges. A ’yellow card’ system for spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was instituted following training of health workers in the selected districts. Thirty-five health professionals (3 medical doctors, 2 technicians, 24 nurses, 4 basic healthcare agents and 2 pharmacy agents) in these districts were trained to diagnose, treat and report ADRs to all medicines using a standardized yellow card system. There were routine site visits to identify and clarify any problems in filling in and sending the forms. One focal person was identified in each district to facilitate communication between the health professionals and the National Pharmacovigilance Unit (NPU). The report form was assessed for quality and causality. The availability of telecommunications and transport was assessed.

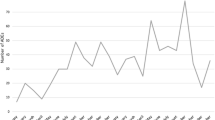

Results: Fourteen months after the first training, 67 ADR reports involving 74 adverse events were received by the NPU involving 25 separate drugs, 16 of which were causally (certainly, probably or possibly) linked to the reaction. Most reported ADRs were dermatological reactions (83.1%). Antimalarial drugs (chloroquine, amodiaquine, quinine, artesunate and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine) were mentioned in 33 (50.8%) of the reports. There were 14 reactions classified as serious and no fatal reactions were reported. There were differences in telecommunications and transport facilities between the districts that might have contributed to the different number of reports.

Conclusion: Health professionals of all levels of education (including basic training) from rural areas could contribute to ADR spontaneous reporting systems. Training, quality-assurance visits and the ongoing presence of focal persons can promote reporting and improve the quality of reports submitted.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lindquist M. Seeing and observing in international pharmacovigilance. Uppsala: Uppsala Monitoring Centre, 2000

Meyboom RH, Egberts AD, Edwards IR, et al. Principles of signal detection in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 1997; 16(6): 355–65

Laporte JR. Princípios basicos de investigação clinica. Madrid: Zeneca Farma, 1993

Edwards IR. The accelerating need for pharmacovigilance. J R Col Physicians Lond 2000; 34(1): 48–51

Edwards IR, Lindquist M, Meyboom R, et al. Pharmacovigilance in focus in drug safety. Uppsala Monitoring Centre, 2000

Uppsala Monitoring Centre. WHO programme for international drug monitoring [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who-umc.org/DynPage.aspx?id=13140 [Accessed 2008 Aug 5]

Haas DW, Ribaudo JR, Kim RB, et al. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz and central nervous system side effects: an adult AIDS clinical trial group study. AIDS 2004; 18: 2391–400

Taylor WR, White NJ. Antimalarial drug toxicity: a review. Drug Safety 2004; 27(1): 25–61

Edwards IR. Safety monitoring of new anti-malarials in immediate post-marketing phase. Med Trop (Mars) 1998; 58(3): 93–6

Simooya O. Introducing pharmacovigilance in public health programmes. Drug Safety 2005; 28(4): 277–86

Programa Nacional de Controlo da Malaria. Normas de tratamento da malaria. Maputo: MISAU, 2001

Programa Nacional de Controlo de ITS/HIV/SIDA. Plano estrategico nacional de combate às ITS/HIV/SIDA do MISAU 2004-2008. Maputo: MISAU, 2004

Instituto Nacional de statistica. Dados demograficos [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ine.gov.mz [Accessed 2005 Sep 21]

Sharp BL, Kleinschmidt I, Streat E, et al. Seven years of regional malaria control collaboration: Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76(1): 42–7

World Health Organization. Safety monitoring of medicinal products: guidelines for setting up and running a pharmacovigilance centre. Uppsala: Uppsala Monitoring Centre, 2000

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP): the first ten years. “Defining the problem and developing solutions”. Dec 2005 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nccmerp.org [Accessed 2008 Aug 05]

Moore N. The role of the clinical pharmacologist in the management of adverse drug reactions. Drug Safety 2001; 24(1): 1–7

Avarez-Requejo A, Carvajal A, Begaud B, et al. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: estimate based on a spontaneous reporting scheme and a sentinel system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 54(6): 483–8

Beigaud B, Martin K, Haramburu F, et al. Rates of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions in France. JAMA 2002; 288: 1588

Figueiras A, Caama F, Gestal J. Metodología de los estudios de utilización de medicamentos en atención primaria. Gac Sanit 2000; 14 Suppl. 3: 7–19

Alvarez Luna F. Pharmacoepidemiology. Drug utilization studies. Part I. Concept and methodology. Seguim Farmacoter 2004; 2(3): 129–36

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sevene, E., Mariano, A., Mehta, U. et al. Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting in Rural Districts of Mozambique. Drug-Safety 31, 867–876 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831100-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831100-00005