Abstract

Objective: To analyse and compare the adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with the use of nimesulide with those associated with diclofenac, ketoprofen, and piroxicam, reported spontaneously in a northern Italian area (Veneto and Trentino).

Methods: Data were obtained from the spontaneous reporting system database of Veneto-Trentino, the principal contributor to the Italian spontaneous surveillance system. All case reports that occurred in association with all formulations of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) under investigation during the period from January 1988 to December 2000, were analysed in detail.

Sales data from June 1996 to May 1999 and prescription data, from 1997 to 2000 from the Veneto region were utilised to select the most widely used NSAIDs to be included in the study. The prescription data were also used to look at the drug use in relation to age.

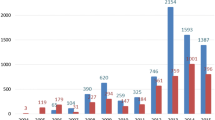

Results: During the study period, 10 608 reports describing 16 571 adverse reactions were entered into the surveillance system. We found 207 case reports for nimesulide, 187 for diclofenac, 174 for ketoprofen, and 137 for piroxicam. Analysis of sales and prescription data revealed that in the Veneto region nimesulide was the most widely prescribed drug followed at a long distance by diclofenac, piroxicam and ketoprofen.

No age-related difference in the use of the four drugs was found. Analysis of the case reports revealed significantly different toxicity profiles for the four drugs. In particular, nimesulide was associated with fewer and less severe gastrointestinal (GI) ADRs compared with the other NSAIDs. Nimesulide was associated with about half the number of GI reactions (10.4%) than the other three NSAIDs (21.2% for diclofenac, 21.7% for ketoprofen, 18.6% for piroxicam). Two previously unreported reactions were also found for piroxicam and ketoprofen.

Conclusions: Nimesulide is the most frequently used NSAID in Italy. Spontaneous reporting data suggest that nimesulide has the most favourable GI tolerability profile of the NSAIDs investigated, with few reports of severe GI reactions. A few reports of hepatic and renal impairment associated with nimesulide suggest caution in patients at risk. Age-related reporting analysis suggests a higher toxicity for diclofenac and piroxicam in the elderly compared with nimesulide and ketoprofen.

This analysis of the Veneto-Trentino database on spontaneous reporting confirms that NSAIDs differ in their tolerability profile, and this fact should be taken into account in the choice of drugs in relation to patient characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Edwards IR. Spontaneous reporting of what? Clinical concerns about drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48: 138–41

Meyboom RHB, Egberts ACG, Edwards IR, et al. Principles of signal detection in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 1997; 16(6): 355–65

Meyboom RHB, Egberts ACG, Gribnau FWJ, et al. Pharmacovigilance in perspective. Drug Saf 1999; 21(6): 429–7

Figueras A, Capellà D, Castel JM, et al. Spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1994; 47: 297–303

Spigset O. Adverse reactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: reports from a spontaneous reporting system. Drug Saf 1999; 20(3): 277–87

Carvajal A, Prieto JR, Requejo AA, et al. Aspirin or acetaminophen? A comparison from data collected by the Spanish Drug Monitoring System. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49(2): 255–61

Routledge PA, Lindquist M, Edwards IR. Spontaneous reporting of suspected adverse reactions to antihistamines: a national and international perspective. Clin Exp Allergy 1999; 29(3): 240–6

Wiholm BE, Emanuelsson S. Drug-related blood dyscrasias in a Swedish reporting system, 1985-1994. Eur J Haematol Suppl 1996; 60: 42–6

Tubert-Bitter P, Begaud B, Moride Y, et al. Comparing the toxicity of two drugs in the framework of spontaneous reporting: a confidence interval approach. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49(1): 121–3

van Puijenbroek EP, Egberts ACG, Meyboom R, et al. Signalling possible drug-drug interactions in a spontaneous reporting system: delay of withdrawal bleeding during concomitant use of oral contraceptives and itraconazole. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 47: 689–93

Meyboom RHB. Good practice in the postmarketing surveillance of medicines. Pharm World Sci 1997; 19: 187–90

Bennet A, Villa G. Nimesulide: an NSAID that preferentially inhibits COX-2, and has various unique pharmacological activities. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2000; 1(2): 277–86

Rainsford KD. Side-effects of anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs: epidemiology and gastrointestinal tract. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1984; 5: 156–9

Fowler PD. Aspirin, paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a comparative review of side effects. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp 1987; 2(5): 338–66

Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Epidemiology of NSAID-induced GI complications. J Rheumatol 1999; 26Suppl. 26: 18–24

Hernández-Diaz S, García Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding and perforation: an overview of epidemiological studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2093–9

Committee on Safety of medicines. Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and serious gastrointestinal adverse reactions-2. BMJ 1986; 292: 1190–1

Wober W. Comparative efficacy and safety of nimesulide and diclofenac in patients with acute shoulder, and a meta-analysis of controlled studied with nimesulide. Rheumatology 1999; 38Suppl. 1: 33–8

García Rodríguez LA, Cattaruzzi C, Troncon MG, et al. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with ketorolac, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, calcium antagonists, and other antihypertensive drugs. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 33–9

Pochobradsky MG, Mele G, Beretta A. Post-marketing survey of nimesulide in the short-term treatment of osteoarthritis. Drugs Exp Clin Res 1991; 17: 197–204

Mele G, Nemeo A, Mellesi L, et al. Post-marketing surveillance on nimesulide in the treatment of 8,354 patients over 60 years old affected with acute and chronic musculo-skeletal diseases [in Italian]. Arch Med Interna 1992; 44: 213–21

Rabasseda X. Safety profile of nimesulide. Ten years of clinical studies. Drugs of Today 1997; 33: 41–50

Rainsford KD. Relationship of nimesulide safety to its pharmacokinetics: assessment of adverse reactions. Rheumatology 1999; 38Suppl. 1: 4–10

Van Steenbergen W, Peeters P, de Bondt J, et al. Nimesulide-induced acute hepatitis: evidence from six cases. J Hepatol 1998; 29: 135–41

Schattner A, Sokolovskaya N, Cohen J. Fatal hepatitis and renal failure during treatment with nimesulide. J Intern Med 2000; 247: 153–5

McCormick PA, Kennedy F, Curry M, et al. COX 2 inhibitor and fulminant hepatic failure. Lancet 1999; 353: 40–1

Conforti A, Leone R, Ghiotto E, et al. Spontaneous reporting of drug-related hepatic reactions from two Italian regions (Lombardy and Veneto). Dig Liver Dis 2000; 32: 716–23

Carson JL, Strom BL, Duff A, et al. Safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with respect to acute liver disease. Arch Int Med 1993; 153: 1331–6

Leone R, Conforti A, Ghiotto E, et al. Nimesulide and renal impairment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 55: 151–4

Senna GE, Passalacqua G, Andri G, et al. Nimesulide in the treatment of patients intolerant of aspirin and other NSAIDs. Drug Saf 1996; 14(2): 94–103

Weber JCP. Epidemiology of adverse reactions to nonteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. In: Rainsford KD, Velo GP, editors. Side-effects of antiinflammatory/analgesic drugs. Advances in inflammation research volume 6. New York (NY): Raven Press, 1984: 1–7

Olsson S, editor. National pharmacovigilance systems: country profiles and overview. 2nd ed. Uppsala, Sweden: The Uppsala Monitoring Centre, 1999 Aug

Safety monitoring of medicinal products: guidelines for setting up and running a pharmacovigilance centre. Uppsala, Sweden: The Uppsala Monitoring Centre, WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, 2000: 22–3

Olsson S. Role of WHO programme on International drug monitoring in co-ordinating world-wide drug safety efforts. Drug Saf 1998; 19: 1–10

Barnes J. Spontaneous ADR reporting in the spotlight. Reactions 1999; 735: 3–4

Lindquist M, Pettersson M, Edwards IR, et al. How does cystitis affect a comparative risk profile of tiaprofenic acid with other non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs? An international study based on spontaneous reports and drug usage data. ADR Signals Analysis Project (ASAP) Team. Pharmacol Toxicol 1997; 80(5): 211–7

Pierfitte C, Bégaud B, Lagnaoui R, et al. Is reporting rate a good predictor of risks associated with drugs? Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 47: 329–31

Rainsford KD. An analysis from clinico-epidemiological data of the principal adverse events from the COX-2 selective NSAID nimesulide, with particular reference to hepatic injury. Inflammopharmacology 1998; 6: 203–1

Naldi L, Conforti A, Venegoni M, et al. Cutaneous reactions to drugs. An analysis of spontaneous reports in four Italian regions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48: 839–46

Bem JL, Mann RD, Rawlins MD. CSM update. Review of yellow cards 1986-1987 [letter]. BMJ 1988; 296: 319

Faich GA, Knapp D, Dreis M, et al. National adverse drug reaction surveillance. 1985. JAMA 1987; 257: 2068–70

Banks AT, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG, et al. Diclofenac-associated hepatotoxicity: analysis of 180 cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration as adverse reactions. Hepatology 1995; 3: 820–7

Olive G, Rey E. Effect of age on the pharmacokinetics of nimesulide. Drugs 1993; 46Suppl. 1: 73–8

Blardi P, Gatti F, Auteri A, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of nimesulide in the treatment of osteoarthritic elderly patients. Int J Tissue React 1992; 14(5): 263–8

Famaey JP. In vitro and in vivo pharmacological evidence of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition by nimesulide: an overview. Inflamm Res 1997; 46: 437–6

Davis R, Brodgen RN. Nimesulide. An update of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 1994; 48: 431–54

Bagheri H, Lhiaubet V, Montastruc JL, et al. Photosensitivity to ketoprofen. Mechanisms and pharmacoepidemiological data. Drug Saf 2000; 22(5): 339–49

Baudot S, Milpied B, Larousse C. Ketoprofene gel et effets secondaires cutanès: bilan d’une enquete sur 337 notifications. Thérapie 1998; 53: 137–44

We are very grateful to the Pharmaceutical Departments of the Veneto Region and the Trento Province, and to the local Health Districts for collecting the adverse reaction forms. Special thanks to Dr Margherita Andretta for the prescription data analysis. The study was supported by a grant from the Veneto region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conforti, A., Leone, R., Moretti, U. et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Related to the Use of NSAIDs with a Focus on Nimesulide. Drug-Safety 24, 1081–1090 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124140-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124140-00006