Summary

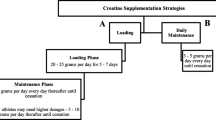

Since the discovery of creatine in 1832, it has fascinated scientists with its central role in skeletal muscle metabolism. In humans, over 95% of the total creatine (Crtot) content is located in skeletal muscle, of which approximately a third is in its free (Crf) form. The remainder is present in a phosphorylated (Crphos) form. Crf and Crphos levels in skeletal muscle are subject to individual variations and are influenced by factors such as muscle fibre type, age and disease, but not apparently by training or gender. Daily turnover of creatine to creatinine for a 70kg male has been estimated to be around 2g. Part of this turnover can be replaced through exogenous sources of creatine in foods, especially meat and fish. The remainder is derived via endogenous synthesis from the precursors arginine, glycine and methionine. A century ago, studies with creatine feeding concluded that some of the ingested creatine was retained in the body. Subsequent studies have shown that both Crf and Crphos levels in skeletal muscle can be increased, and performance of high intensity intermittent exercise enhanced, following a period of creatine supplementation. However, neither endurance exercise performance nor maximal oxygen uptake appears to be enhanced. No adverse effects have been identified with short term creatine feeding. Creatine supplementation has been used in the treatment of diseases where creatine synthesis is inhibited.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hunter A. Monographs on biochemistry: creatine and creatinine. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1928

Lundsgaard E. Weitere Untersuchungen über Muskelkontraktionen ohne Milchsäurebildung. Biochem Z 1930; 227: 51

Bergström J. Muscle electrolytes in man: determined by neutron activation analysis on needle biopsy specimens — study on normal subjects, kidney patients and patients with chronic diarrhoea. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1962; 14: 1–110

Hultman E, Bergström J, Anderson NM. Breakdown and resynthesis of phosphorylcreatine and adenosine triphosphate in connection with muscular work in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1967; 19: 56–66

Balsom PD, Ekblom B, Söderlund K, et al. Creatine supplementation and dynamic high-intensity intermittent exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1993; 3: 143–9

Balsom PD, Harridge SDR, Söderlund K, et al. Creatine supplementation per se does not enhance endurance exercise performance. Acta Physiol Scand 1993; 149: 521–3

Greenhaff PL, Casey A, Short AH, et al. Influence of oral creatine supplementation on muscle torque during repeated bouts of maximal voluntary exercise in man. Clin Sci 1993; 84: 565–71

Harris R, Söderlund K, Hultman E. Elevation of creatine in resting and exercise muscles of normal subjects by creatine supplementation. Clin Sci 1992; 83: 367–74

Devlin TM. Textbook of biochemistry: with clinical correlations. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1992: 518

Walker JB. Creatine: biosynthesis, regulation and function. In: Meister A, editor. Advances in enzymology and related areas of molecular biology. New York: John Wiley, 1979: 177–241

Hoberman HD, Sims EAH, Peters JH. Creatine and creatinine metabolism in the normal male adult studied with the aid of isotopic nitrogen. J Biol Chem 1948; 172: 45–58

Walker JB. Metabolic control of creatine biosynthesis, 1: effect of dietary creatine. J Biol Chem 1960; 235: 2357–61

Hoogwerf BJ, Laine DC, Greene E. Urine C-peptide and creatinine (Jaffe method) excretion in healthy young adults on varied diets: sustained effects of varied carbohydrate, protein and meat content. Am J Clin Nutr 1986; 43: 350–60

Delanghe J, De Slypere J-P, De Buyzere M, et al. Normal reference values for creatine, creatinine, and carnitine are lower in vegetarians. Clin Chem 1989; 35: 1802–3

Bergmeyer HU. Methoden der Enzymatischen Analyse. Weinheim: Verlag Chemie, 1970

Harris RC, Hultman E, Nordesjö L-O. Glycogen, glycolytic intermediates and high-energy phosphates determined in biopsy samples of musculus quadriceps femoris of man at rest: methods and variance of values. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1974; 33: 109–20

Söderlund K, Hultman E. Effects of delayed freezing on content of Phosphagens in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 1986; 61: 832–5

McCully KK, Kent JA, Chanve B. Application of 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy to the study of athletic performance. Sports Med 1988; 5: 312–21

Rehunen S, Härkönen M. High-energy phosphate compounds in human slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibres. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1980; 40: 45–54

Möller P, Bergström J, Fürst P, et al. Effect of aging on energy rich Phosphagens in human skeletal muscle. Clin Sci 1980; 58: 553–5

Rehunen S, Näveri H, Kuoppasalmi K, et al. High-energy phosphate compounds during exercise in human slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibres. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1982; 42: 499–506

Forsberg AM, Nilsson E, Werneman J, et al. Muscle composition in relation to age and sex. Clin Sci 1991; 81: 249–56

Möller P, Brandt R. Skeletal muscle adaptation to aging and to respiratory and liver failure [dissertation]. Stockholm: Karol-inska Institute, 1981

Essen B. Studies on the regulation of metabolism in human skeletal muscle using intermittent exercise as an experimental model. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 1978; 454: 7–64

Tesch PA, Thorsson A, Fujitsuka N. Creatine phosphate in fiber types of skeletal muscle before and after exhaustive exercise. J Appl Physiol 1989; 66: 1756–9

Söderlund K, Greenhaff P, Hultman E. Energy metabolism in type I and type II human muscle fibres during short term electrical stimulation at different frequencies. Acta Physiol Scand 1992; 144: 15–22

Edström L, Hultman E, Sahlin K, et al. The contents of high-energy phosphates in different fibre types in skeletal muscles from rat, guinea pig and man. J Physiol 1982; 332: 47–58

Karlsson J, Diamant B, Saltin B. Muscle metabolites during sub-maximal and maximal exercise in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1971; 26: 385–94

Gariod L, Binzoni T, Feretti G, et al. Standardisation of 31 phosphorus-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy determinations of high energy phosphates in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 1994; 68: 107–10

Bernús G, Gonzale De Suso JM, Alonso J, et al. 31P-MRS of quadriceps reveals quantitative differences between sprinters and long-distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25: 479–84

Grimby G, Björntorp P, Fahlen M, et al. Metabolic effects of isometric training. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1973; 31: 301–5

Thorstensson A, Sjödin B, Karlsson J. Enzyme activities and muscle strength after ‘sprint training’ in man. Acta Physiol Scand 1975; 94: 313–8

Houston ME, Thomson JA. The response of endurance adapted adults to intense anaerobic training. Eur J Appl Physiol 1977; 36: 207–13

Boobis LH, Williams C, Wootton SA. Influence of sprint training on muscle metabolism during brief maximal exercise in man. J Physiol 1983; 342: 36P–37P

Sharp RL, Costill DL, Fink WJ, et al. Effects of eight weeks of bicycle ergometer sprint training on human muscle buffer capacity. Int J Sports Med 1986; 7: 13–7

Nevill ME, Boobis LH, Brooks S, et al. Effect of treadmill training on muscle metabolism during treadmill sprinting. J Appl Physiol 1989; 67: 2376–82

Hellsten-Westing Y, Norman B, Balsom PD, et al. Decreased resting levels of adenine nucleotides in human skeletal muscle after high-intensity training. J Appl Physiol 1993; 74: 2523–8

Karlsson J, Nordesjö L-O, Jorfeldt L, et al. Muscle lactate, ATP and CP levels during exercise after physical training in man. J Appl Physiol 1972; 33: 199–203

Yakovlev NN. Biochemistry of sport in the Soviet Union: beginning, development, and present times. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1975; 7: 237–47

Eriksson BO, Gollnick PD, Saltin B. Muscle metabolism and enzyme activities after training in boys 11–13 years old. Acta Physiol Scand 1973; 87: 485–97

McDougall JD, Ward GR, Sale DG, et al. Biochemical adaptation of human skeletal muscle to heavy resistance training and immobilisation. J Appl Physiol 1977; 43: 700–3

Fitch CD. Significance of abnormalities of creatine metabolism. In: Rowland LP, editor. Pathogenesis of human muscular dystrophies. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1977: 328–40

Nordemar R, Lövgren O, Fürst P, et al. Muscle ATP content in rheumatoid arthritis — a biopsy study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1974; 34: 185–91

Bengtsson A. Primary fibromyalgia: a clinical study. Linköping: Linköping University; 1986. Medical dissertation no.: 224

Karlsson J, Willerson JT, Leshin SJ, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolites in patients with cardiogenic shock or severe congestive heart failure. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1975; 35: 73–9

Bergström J, Boström H, Fürst P, et al. Preliminary studies of energy rich Phosphagens in muscle from severely ill patients. Crit Care Med 1976; 4: 197–204

Gertz I, Hedenstierna G, Hellers G, et al. Muscle metabolism in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease and acute respiratory failure. Clin Sci 1977; 52: 395–403

Möller P, Bergström J, Fürst P, et al. Energy-rich Phosphagens, electrolytes and free amino acids in leg skeletal muscle of patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Acta Med Scand 1981; 211: 187–93

Jakobsson P, Jorfeldt L, Brundin A. Skeletal muscle metabolites and fibre types in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with and without chronic respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 1990; 3: 192–6

Wallimann T, Wyss M, Brdiczka D, et al. Intracellular compart-mentation, structure and function of creatine kinase isoenzymes in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands: the ‘phosphocreatine circuit’ for cellular energy homeostasis. Biochem J 1992; 281: 21–40

Bessman SP, Geiger PJ. Transport of energy in muscle: the phosphorylcreatine shuttle. Science 1981; 211: 448–52

Spriet LL, Söderlund K, Bergström M, et al. Anaerobic energy release in skeletal muscle during electrical stimulation in men. J Appl Physiol 1987; 62: 611–5

Jones NL, McCartney N, Graham T, et al. Muscle performance and metabolism in maximal isokinetic cycling at slow and fast speeds. J Appl Physiol 1985; 59: 132–6

Gaitanos G, Williams C, Boobis LH, et al. Human muscle metabolism during intermittent maximal exercise. J Appl Physiol 1993; 75: 712–9

Greenhaff PL, Nevill ME, Söderlund K, et al. The metabolic responses of human type I and II muscle fibres during maximal treadmill sprinting. J Physiol 1994; 478: 149–55

Bogdanis GC, Nevill ME, Boobis LH, et al. Recovery of power output and muscle metabolites following 30 s of maximal sprint cycling. J Physiol. In press

Harris RC, Edwards RHT, Hultman E, et al. The time course of phosphorylcreatine resynthesis during recovery of the quadriceps muscle in man. Pflugers Arch 1976; 367: 137–42

Sahlin K, Harris RC, Hultman E. Resynthesis of creatine phosphate in human muscle after exercise in relation to intramuscular pH and availability of oxygen. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1979; 39: 551–8

Söderlund K, Hultman E. ATP and phosphocreatine changes in single human muscle fibers after intense electrical stimulation. Am J Physiol 1991; 261: E737–E741

Tesch PA, Wright JE. Recovery from short term intense exercise: its relation to capillary supply and blood lactate concentration. Eur J Appl Physiol 1983; 52: 98–103

Broberg S, Sahlin K. Adenine nucleotide degradation in human skeletal muscle during prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol 1989; 67: 116–22

Norman B, Sollevi A, Kaijser L, et al. ATP breakdown products in human skeletal muscle during prolonged exercise to exhaustion. Clin Physiol 1987; 7: 503–10

Crim MC. Creatine metabolism in men: urinary creatine and creatinine excretions with creatine feeding. J Nutr 1975; 105: 428–38

Crim MC, Calloway DH, Margen S. Creatine metabolism in men: creatine pool size and turnover in relation to creatine intake. J Nutr 1976; 106: 371–81

Fitch CD, Shields RP. Creatine metabolism in skeletal muscle, 1: creatine movement across muscle membranes. J Biol Chem 1966; 241: 3611–4

Fitch CD. Creatine metabolism in skeletal muscle, III: specificity of the creatine entry process. J Biol Chem 1968; 243: 2024–7

Ingwall JS. Creatine and the control of muscle-specific protein synthesis in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Circ Res 1976; 38: 115–22

Bessman SP, Savabi F. The role of the phosphocreatine energy shuttle in exercise and muscle hypertrophy. In: Taylow AW, Gollnick PD, Green HJ, et al., editors. International series on sport sciences, vol. 21. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 1988: 167–78

Sipilä I, Rapola J, Simell O, et al. Supplementary creatine as a treatment for gyrate atrophy of the choroid retina. N Engl J Med 1981; 304: 867–70

Gerber GB, Gerber G, Koszalka TR, et al. Creatine metabolism in vitamin E deficiency in the rat. Am J Physiol 1962; 202: 453–60

Koszalka TR, Andrew CL. Effect of insulin on the uptake of creatine-1-14C by skeletal muscle in normal and X-irradiated rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1972; 139: 1265–71

Greenhaff PL, Bodin K, Söderlund K, et al. The effect of oral creatine supplementation on skeletal muscle phosphocreatine resynthesis. Am J Physiol 1994; 266: E725–E730

Söderlund K, Balsom PD, Ekblom B. Creatine supplementation and high-intensity exercise: influence on performance and muscle metabolism. Clin Sci 1994; 87 Suppl.: 120

Harridge SDR, Balsom PD, Söderlund K. Creatine supplementation and electrically evoked human muscle fatigue. Clin Sci 1994: 87 (Suppl.): 124

Östberg K, Söderlund K. Kreatin. Skidskytte 1993; 5: 16–7

Williams C. Metabolic aspects of fatigue. In: Reilly T, Sichir N, Snell P, et al., editors. Physiology of sports. London: E & FN Spon, 1990: 3–39

Vannas-Sulonen K, Sipilä I, Vannas A, et al. Gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina: a five year follow-up of creatine supplementation. Ophthalmology 1985; 92: 1719–27

Walker JB. Metabolic control of creatine biosynthesis, II: restoration of transamidinase activity following creatine repression. J Biol Chem 1960; 236: 493–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balsom, P.D., Söderlund, K. & Ekblom, B. Creatine in Humans with Special Reference to Creatine Supplementation. Sports Med 18, 268–280 (1994). https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199418040-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199418040-00005