Abstract

Background

Incidence of hip fractures in men is expected to increase, yet little is known about consequences of hip fracture in men compared to women. It is important to investigate differences at time of fracture using the newest technologies and methodology regarding metabolic, physiologic, neuromuscular, functional, and clinical outcomes, with attention to design issues for recruiting frail older adults across numerous settings.

Objectives

To determine whether at least moderately-sized sex differences exist across several key outcomes after a hip fracture.

Design, Setting, & Participants

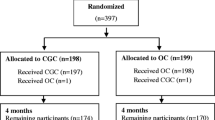

This prospective cohort study (Baltimore Hip Studies 7th cohort [BHS-7]) was designed to include equal numbers of male and female hip fracture patients to assess sex differences across various outcomes post-hip fracture. Participants were recruited from eight hospitals in the Baltimore metropolitan area within 15 days of admission and were assessed at baseline, 2, 6 and 12 months post-admission.

Measurements

Assessments included questionnaire, functional performance evaluation, cognitive testing, measures of body composition, and phlebotomy.

Results

Of 1709 hip fracture patients screened from May 2006 through June 2011, 917 (54%) were eligible and 39% (n=362) provided informed consent. The final analytic sample was 339 (168 men and 171 women). At time of fracture, men were sicker (mean Charlson score= 2.4 vs. 1.6; p<0.001) and had worse cognition (3MS score= 82.3 vs. 86.2; p<0.05), and prior to fracture were less likely to be on bisphosphonates (8% vs. 39%; p<0.001) and less physically active (2426 kilocalories/week vs. 3625; p<0.001).

Conclusions

This paper provides the study design and methodology for recruiting and assessing hip fracture patients and evidence of baseline and pre-injury sex differences which may affect eventual recovery one year later.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stevens JA, Rudd RA. The impact of decreasing U.S. hip fracture rates on future hip fracture estimates. Osteoporos In. 2013;24(10):2725–2728.

Brown CA, Starr AZ, Nunley JA. Analysis of past secular trends of hip fractures and predicted number in the future 2010–2050. J Orthop Traum. 2012;26(2):117–122.

Lofman O, Berglund K, Larsson L, et al. Changes in hip fracture epidemiology: redistribution between ages, genders and fracture types. Osteoporos In. 2002;13(1):18–25.

Abrahamsen B, van. Staa T, Ariely R, et al. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos In. 2009;20(10):1633–1650.

Hawkes WG, Wehren L, Orwig D, et al. Gender differences in functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol Med Sc. 2006;61A(5):495–499.

Orwig DL, Chan J, Magaziner J. Hip fracture and its consequences: differences between men and women. Orthop Clin North A. 2006;37(4):611–622.

Wehren LE, Hawkes WG, Hebel JR, et al. Bone mineral density, soft tissue body composition, strength, and functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol Med Sc. 2005;60(1):80–84.

Wehren LE, Hawkes W, Orwig D, et al. Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: The role of infection. J Bone Miner Re. 2003;18(12):2231–2237.

Panula J, Pihlajamaki H, Mattila VM, et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disor. 2011;12:105.

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, et al. Meta-analysis: Excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Me. 2010;152(6):380–390.

Doherty TJ. The influence of aging and sex on skeletal muscle mass and strength. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Car. 2001;4(6):503–508.

LeBlanc ES, Wang PY, Lee CG, et al. Higher testosterone levels are associated with less loss of lean body mass in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Meta. 2011;96(12):3855–3863.

Waters DL, Yau CL, Montoya GD, et al. Serum sex hormones, IGF-1, and IGFBP3 exert a sexually dimorphic effect on lean body mass in aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sc. 2003;58(7):648–652.

Institute of Medicine. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? 2001. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Woodward LM, Clemson L, Moseley AM, et al. Most functional outcomes are similar for men and women after hip fracture: a secondary analysis of the enhancing mobility after hip fracture trial. BMC Geriat. 2014;14(1):1–7.

Lieberman D, Lieberman D. Rehabilitation following hip fracture surgery: a comparative study of females and males. Disabil Rehabi. 2004;26(2):85–90.

Koval KJ, Skovron ML, Aharonoff GB, et al. Ambulatory ability after hip fracture: A prospective study in geriatric patients. Clin Orthop Relat Re. 1995;310:150–159.

Niemela K, Leinonen R, Laukkanen P. The effect of geriatric rehabilitation on physical performance and pain in men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2011;52(3):e129–133.

Aberg AC. Gender comparisons of function-related dependence, pain and insecurity in geriatric rehabilitation. J Rehabil Me. 2005;37(6):378–384.

Bassuk SS, Murphy JM. Characteristics of the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam among elderly persons. J Clin Epidemio. 2003;56(7):622–628.

Cawthon PM, Ewing SK, McCulloch CE, et al. Loss of hip BMD in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study. J Bone Miner Re. 2009;24(10):1728–1735.

Chumlea WC, Roche AF, Steinbaugh ML. Estimating stature from knee height for persons 60 to 90 years of age. J Am Geriatr So. 1985;33(2):116–120.

Chulmea W. Methods of nutritional anthropometric assessment for special groups. 1988. Human Kinetics Books, Champaign, Ill

Jette AM. Functional Status Index: reliability of a chronic disease evaluation instrument. Arch Phys Med Rehabi. 1980;61(September):395–401.

Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures. 1988. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM, et al. A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1993;25(5):628–642.

Zimmerman SI, Williams G, Lapuerta P, et al. The lower extremity gain scale (LEGS): A performance-based measure to assess hip fracture recovery [abstract]. Gerontologis. 2002;42(October):238.

Hawkes WG, Williams GR, Zimmerman S, et al. A clinically meaningful difference was generated for a performance measure of recovery from hip fracture. J Clin Epidemio. 2004;57:1019–1024.

Zimmerman S, Hawkes WG, Hebel JR, et al. The Lower Extremity Gain Scale: a performance-based measure to assess recovery after hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Reha. 2006;87:430–436.

Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Geronto. 1994;49(2):M85–94.

Ashford RF, Nagelburg S, Adkins R. Sensitivity of the Jamar Dynamometer in detecting submaximal grip effort. J Hand Sur. 1996;21(3):402–405.

Marino M, Gleim GW. Muscle strength and fiber typing. Clin Sports Me. 1984;3(1):85–100.

ActiGraph. ActiGraph Analysis Software. 2004.

Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiat. 1987;48:314–318.

Bornstein RA, Suga LJ. Educational level and neuropsychological performance in healthy elderly subjects. Dev Neuropsycho. 1988;4(1):17–22.

Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE, et al. Neuropsychological tests’ norms above age 55: COWAT, BNT, MAE Token, WRAT-R Reading, AMNART, STROOP, TMT, and JLO. Clin Neuropsycho. 1996;10(3):262–278.

Richardson ED, Marottoli RA. Education-specific normative data on common neuropsychological indices for individuals older than 75 years. Clin Neuropsycho. 1996;10(4):375–381.

Va. Gorp WG, Satz P, Mitrushina M. Neuropsychological processes associated with normal aging. Develop Neuropsycho. 1990;6(4):279–290.

Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, et al. Mayo’s Older African Americans Normative Studies: norms for Boston Naming Test, Controlled Oral Word Association, Category Fluency, Animal Naming, Token Test, Wrat-3 Reading, Trail Making Test, Stroop Test, and Judgment of Line Orientation. Clin Neuropsycho. 2005;19(2):243–269.

Ashendorf L, Jefferson AL, O’Connor MK, et al. Trail Making Test errors in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsycho. 2008;23(2):129–137.

Hooper HE. Hooper Visual Organization Test (VOT) Manual. 1983. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles

Nadler JD, Grace J, White D, et al. Laterality differences in quantitative and qualitative Hooper performance. Arch of Clin Neuropsycho. 1996;11:223–229.

Nabors NA, Vangel SJ, Lichtenberg PA, et al. Normative and clinical utility of the Hooper Visual Organization Test with geriatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Geropsycholog. 1997;2:191–198.

Walsh PF, Lichtenberg P. Hooper Visual Organization Test performance in geriatric rehabilitation. Clin Geronto. 1997;27:3–11.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Mea. 1977;1:385–401.

House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. Am J Epidemio. 1982;116:123–140.

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psycho. 1994;67(6):1063–1078.

Resnick B, Inguito P. Testing the reliability and validity of the Resilience Measure. Arch Psychiatr Nur. 2011(25):11–20.

Wagnild G. Resilience and successful aging. Comparison among low and high income older adults. J Gerontol Nur. 2003;29(12):42–49.

Herr KA, Mobily PR. Complexities of pain assessment in the elderly. Clinical considerations. J Gerontol Nur. 1991;17(4):12–19.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sc. 2001;56(3):M146–M156.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 1988. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, et al. Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sc. 2000;55(9):M498–M507.

Sterling RS. Gender and race/ethnicity differences in hip fracture incidence, morbidity, mortality, and function. Clin Orthop Relat Re. 2011;469(7):1913–1918.

Becker C, Crow S, Toman J, et al. Characteristics of elderly patients admitted to an urban tertiary care hospital with osteoporotic fractures: correlations with risk factors, fracture type, gender and ethnicity. Osteoporos In. 2006;17(3):410–416.

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, et al. Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Agein. 2010;39(2):203–209.

Wehren LE, Hawkes WG, Orwig DL, et al. Gender differences in mortality after hip fracture: the role of infection. J Bone Miner Re. 2003;18(12):2231–2237.

Endo R, Kamakura M, Miyauchi K, et al. Identification and characterization of genes involved in the downstream degradation pathway of gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. J Bacterio. 2005;187(3):847–853.

Pande I, Scott DL, O’Neill TW, et al. Quality of life, morbidity, and mortality after low trauma hip fracture in men. Ann Rheum Di. 2006;65(1):87–92.

Arinzon Z, Shabat S, Peisakh A, et al. Gender differences influence the outcome of geriatric rehabilitation following hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2010;50(1):86–91.

Shardell M, D’Adamo C, Alley DE, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, transitions between frailty states, and mortality in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti Study. J Am Geriatr So. 2012;60(2):256–264.

Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, Morrison RS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hip fracture patients: timing of detection and longitudinal follow-up. J Amer Geriatr So. 2003;51(9):1227–1236.

Berry S, Samelson EJ, Bordes M, et al. Survival of aged nursing home residents with hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sc. 2009;64A(7):771–777.

Samuelsson B, Hedstrom MI, Ponzer S, et al. Gender differences and cognitive aspects on functional outcome after hip fracture—a 2 years’ follow-up of 2,134 patients. Age Agein. 2009;38(6):686–692.

Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Plassman BL, et al. An adaptation of the modified mini-mental state examination: analysis of demographic influences and normative data: the cache county study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neuro. 2002;15(1):28–38.

Lewiecki EM. Managing osteoporosis: challenges and strategies. Cleve Clin J Me. 2009;76(8):457–466.

Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, et al. Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr So. 2010;58(4):650–657.

CDC. Facts About Physical Activity. 2014. (https://doi.org/www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/facts.html). Accessed 10 Octobe. 2017

Talkowski JB, Lenze EJ, Munin MC, et al. Patient participation and physical activity during rehabilitation and future functional outcomes in patients after hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehabi. 2009;90(4):618–622.

Rodaro E, Pasqualini M, Iona LG, et al. Functional recovery following a second hip fracture. Eura Medicophy. 2004;40(3):179–183.

Wainwright SA, Marshall LM, Ensrud KE, et al. Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Meta. 2005;90(5):2787–2793.

D. Monaco M, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, et al. Muscle mass and functional recovery in women with hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabi. 2006;85(3):209–215.

D. Monaco M, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, et al. Muscle mass and functional recovery in men with hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabi. 2007;86(10):818–825.

Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Vallero F, et al. Men recover ability to function less than women do: an observational study of 1094 subjects after hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabi. 2012;91(4):309–315.

Fox KM, Magaziner J, Hawkes WG, et al. Loss of bone density and lean body mass after hip fracture. Osteoporos In. 2000;11:31–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix 1

. Study Measures Collected by Time Point; BHS-7 2006–2011

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orwig, D., Hochberg, M., Gruber-Baldini, A. et al. Examining Differences in Recovery Outcomes between Male and Female Hip Fracture Patients: Design and Baseline Results of A Prospective Cohort Study from the Baltimore Hip Studies. J Frailty Aging 7, 162–169 (2018). https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2018.15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2018.15