Abstract

In this article, we present a theoretically well-founded coaching concept, which can be assigned to the cognitive-behavioral area and which aims to optimally deal with stress. The coaching concept is based on Lazarus’ transactional theory of stress and coping. The three coaching sessions based on this theory are described in as much detail as possible. We explain which exercises can be used and how – both during and between the coaching sessions – in order to provide the best possible support for stress management and goal attainment. The specific procedure is illustrated with the case study “Mr. Smith” and reflected from the coach’s perspective. The description of the cognitive-behavioral stress management coaching (abbreviated to CBSM coaching) and the case study therefore offer both suggestions for experienced coaches and a good guide for newcomers to the field. The effectiveness of the CBSM coaching has already been empirically proven. The results of this already published evaluation study will be presented in the overview. With the theory-based development and the practical presentation of the CBSM coaching concept, a contribution should be made to further close the gap that sometimes arises between coaching research and practice.

Zusammenfassung

In diesem Bericht wird ein theoretisch fundiertes Coaching-Konzept, welches dem kognitiv-behaviorale Bereich zuzuordnen ist und den optimalen Umgang mit Stress zum Ziel hat, beschrieben. Das Coaching-Konzept basiert auf der etablierten Transaktionstheorie zur Entstehung und dem Umgang mit Stress von Lazarus. Die darauf aufbauenden drei Coaching-Sitzungen werden möglichst detailliert beschrieben. Es wird erläutert, welche Übungen wie verwendet werden können – sowohl während als auch zwischen den Coaching-Sitzungen –, um das Stressmanagement sowie die Zielerreichung bestmöglich zu unterstützen. Das konkrete Vorgehen wird anhand der Fallstudie „Mr. Smith“ illustriert und aus Perspektive des Coaches reflektiert. Die Beschreibungen des kognitiv-behavioralen Stressmanagement-Coachings (abgekürzt CBSM-Coaching) und der Fallstudie bieten daher sowohl Anregungen für erfahrene Coaches als auch einen guten Leitfaden für Newcomer in diesem Bereich an. Die Wirksamkeit des CBSM-Coachings wurde bereits empirisch belegt. Die Ergebnisse der publizierten Studie werden im Überblick dargestellt. Mit der theoriebasierten Entwicklung sowie der praxisnahen Darstellung des CBSM-Coaching-Konzepts soll ein Beitrag geleistet werden, um die manches Mal auftretenden Lücke zwischen Coaching-Forschung und -Praxis weiter zu schließen.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Coaching as an intervention showed good results in practice and research (e.g., Greif 2016; Grant 2014; Jones et al. 2014; Losch et al. 2016; Theeboom et al. 2014; Zanchetta et al. 2020). Coaching is no longer used exclusively in an organizational but also in a private context and can be helpful in increasing performance, in stress management and in achieving work-related and personal goals (Palmer et al. 2003). However, theory-driven developed coachings have not been dealt with in many papers yet. Hence, the goal of the present report was to show the development of a theory-driven cognitive-behavioral coaching to manage stress.

Empirical research demonstrated that employees’ chronic exposure to work-related stressors was at the expense of mental (Michie and Williams 2003; Milner et al. 2018) and physical (Nixon et al. 2011) health, cognitive functioning (Linden et al. 2005), productivity (Halkos and Bousinakis 2010) and performance (Gilboa et al. 2008). Increased job stress was further shown to be associated with lower work satisfaction, higher intentions to quit (Shader et al. 2001) and actual turnover (Griffeth et al. 2000). Ultimately, chronic occupational stress imposes a considerable financial burden on individuals, organizations and societies (EU-OSHA 2014). A systematic review examining the economic impact of work-related stress across Europe, Australia, Canada and the United States suggested that the total estimated costs, including those related to productivity losses and healthcare and medical needs, ranged from U.S. $ 221.13 million to $ 187 billion annually (Hassard et al. 2017). Accordingly, the impact of various stress management programs has been studied. A meta-analytic review of primary resilience-building interventions designed to prevent stress-related problems, among other things, found a positive impact on prevention efforts (Vanhove et al. 2016). In particular, dyadic interventions such as coaching were found to be superior to classroom-based group, train-the-trainer and computer-based delivery formats. Further meta-analyses (Richardson and Rothstein 2008; van der Klink et al. 2001) were able to show that cognitive-behavioral interventions were consistently more effective than other stress management strategies (e.g. relaxation and meditation techniques, organizational level interventions). Considering these findings, a cognitive-behavioral stress management coaching should be helpful to improve stress management (Junker et al. 2020).

2 From Theory to Practice

To develop a theory-driven coaching for managing stress, we made use of one of the most popular explanation models regarding stress development, namely the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). According to this theory, a central aspect for experiencing stress is the judgement of a situation as challenging (Ladegård 2011; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). It is postulated that stress is a result of an interplay between a person who has specific motives (e.g., goals and values) and beliefs (e.g., self-esteem, mastery, sense of control) and the immediate environment that is characterized by certain demands (e.g., pressure at work), resources (e.g., social support of colleagues) and constraints (e.g., company policies). A person’s subjective cognitive appraisal (primary appraisal) of the situation as dangerous, harmful, threatening, or challenging in relation to their personal goals and well-being leads to the regarding stress response. A secondary appraisal follows as a person relates it to resources regarding the situation and possible coping options. When the person evaluates the situation as straining and exceeding their coping capacity, it results in the occurrence of stress (Lazarus 1990; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). For example, if a person – let us call her Ms. Jones – has the goal to organize an excellent international conference with many participants (stressor). Normally, this would be no problem for her (primary appraisal: positive or irrelevant). However, in this case, the allocated time for its organization is limited and the colleagues who helped her organize previous conferences are busy working on other projects (secondary appraisal: insufficient resources). Hence, Ms. Jones is aware of the onset of stress (the whole model is displayed in Fig. 1, left side; taken unchanged from File:Transactional Model of Stress and Coping – Richard Lazarus.svg 2016, October 16).

The process of the transactional model of stress is illustrated on the left. This part of the Figure was taken unchanged from File:Transactional Model of Stress and Coping – Richard Lazarus.svg (2016, October 16). The CBSM coaching approach on the right was added and connected to the transactional model of stress process by the authors

Coaching has already been theorized as well as empirically shown to be able to address all aspects of the transaction process of stress and coping, beginning with the appraisal of the stressors and coping resources culminating in the rearrangement of behavior related strategies (Green et al. 2007; Ladegård 2011; Lauterbach 2008). Through coaching clients could gain the ability for self- and problem-reflection, thereby improving their viewpoint towards the stressors (primary appraisal). In addition, they could activate resources (secondary appraisal) and the development of transformation strategies to contribute to the resolution-process (coping response). The coaching should contain a precise goal-definition in combination with a resolution-oriented phase of self- and problem-reflection, as well as the improvement of coping-strategies through cognitive reappraisal and observational learning (Lauterbach 2008). Building on this background, as well as on an established coaching concept concerning career development (Braumandl et al. 2013), we created our cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) coaching.

3 Structure and Setting of the CBSM Coaching

Bearing in mind the high costs of coachings, we decided to create a short-time intervention consisting of three coaching sessions, each with a duration of 1.5 h at intervals of one or two weeks. At the beginning of the CBSM coaching, we focus on working on the primary appraisal according to the transactional stress model. Therefore, clients should be motivated to develop an awareness for their individual stressful situations in the first session. In the second and third sessions the clients will be supported in the selection and application of individual resources and coping strategies through self-reflection inducing exercises. Finally, the reappraisal of prospective situations and goal attainment should be provided through stress processing plans. As the CBSM coaching should be goal-focused, each coaching session should start with a goal attainment scale to determine the current goal status. Such a scale should include the numbers from 1 to 10, whereby 1 indicates being far away from attaining the goal to 10 – goal attainment is completed. Additionally, as the CBSM coaching should be sustainable and transformable, after each session, clients should be given exercises which can be incorporated into their daily routine. To ensure success, the experiences made between the CBSM coaching sessions should be reviewed with the coach in the following session.

3.1 First Session of the CBSM Coaching

In the first phase of the CBSM coaching process the coach should work out the primary motivation of the client to make use of the CBSM coaching. In this regard, the coach should discuss past experiences and activities regarding stressful situations with the client. Moreover, the client’s expectations regarding the CBSM coaching process as well as regarding the coach as a person should be determined. The coach should clearly state coaching standards, the coaching framework and the working methods in the CBSM coaching.

As stated above, the CBSM coaching should be goal-focused. Therefore, each coaching session should start with the goal attainment scale to determine the current goal status. According to the transactional stress model, the interpretation of stimuli is crucial in the development of stress. Therefore, working on motives and precise goal-definition is useful for adequate interpretations of stimuli. If the clients are most aware of their goals, it is easier for them to primary appraise stimuli as positive, irrelevant or dangerous. With regard to the selection of goals, the client is free to choose them with the following restriction – they should be related to private or professional stress issues. The clients’ selected goals should be defined in detail in the first session. Quantifiable goals and sub-goals for the CBSM coaching process should be formulated according to the SMART way to write goals (Doran 1981). Hence, the goals should be specific (S), measureable (M), assignable (A), realistic (R) and time-related (T). The coaches should ask the clients which specific area of improvement the goal will have (S). They should evaluate how the goal will be quantified or at which indicators the clients see progress (M). The clients should specify who will do it (A) and state what results can realistically be achieved, given the available resources (R). Lastly, clients should specify when the goal(s) will be achieved (T). When they have finished the SMART goal definition, they should write them on moderation cards for recurrent use in the following coaching sessions. The clients should be given the opportunity to write down up to three formulated goals with the support of the coach. Afterward, the clients will be able to discuss their conclusion of the first CBSM coaching session to consolidate the SMART goal finding process. Thus, the goals are content-oriented based on the clients’ stress-related issues. Methodically, the selected goals are formulated using the SMART principle in order to make them quantifiable and to stimulate problem- and self-related reflection processes within the first session.

According to the transactional model, further to processing stressors, analyzing resources is the crucial part during the secondary appraisal. Therefore, the clients will be assigned the task energy card (Braumandl et al. 2013; Weisweiler et al. 2012) as a work at home exercise at the end of the first coaching session. During this task, clients will be encouraged to start a self-reflection process regarding the stressors (which draw energy) and facilitators of wellbeing (which give energy) in their various areas of life (i.e., family, self, study or work situation). The clients will receive a worksheet where seven boxes with the headings friends and social contacts, partnership, self, free time, family and study/work and one without any heading are displayed. Each box contains a section for draws energy and gives energy. If a topic is not suitable, the client may replace it with another more personally important one (a template can be found in Weisweiler et al. 2012). The coach should inform the client that filling in the energy card will take around 40 min. Additionally, the clients should receive the questionnaire “Stressverarbeitungsfragebogen” (SVF-78; Janke et al. 1985), regarding the processing of stress, to fill in at home (processing time 10–15 min). The stress processing questionnaire will be evaluated and analyzed by the coach before the second CBSM coaching session to highlight various positive (i.e., stress relaxation, need for social support) and negative (i.e., escape, rumination) stress coping strategies.

3.2 Second CBSM Coaching Session

The main content of the second CBSM coaching session should be the review of the coaching goal status, the filled in energy card (Braumandl et al. 2013; Weisweiler et al. 2012) and the stress processing questionnaire (SVF-78; Janke et al. 1985). In general, the coach should use goal- and result-oriented questions to stimulate self-reflection and to connect the findings obtained by the materials to the postulated goals of the clients defined in a SMART way within the first session. With the use of the energy card the relevant areas of life, including all positive and negative influences, can be clarified. This helps the clients and makes them more aware of the current influences on their stress level and wellbeing, thereby affecting their secondary appraisal positively. These insights could support the clients in the deliberate facilitation of the positive aspects of different areas of life and regarding their coaching goals.

Again, according to the transactional model, the clients should learn how to overcome stress by identifying stress processing mechanisms and develop useful coping strategies. Therefore, the profile sheet of the evaluated stress processing questionnaire (SVF-78; Janke et al. 1985) should be discussed with the clients to determine all positive and negative strategies regarding the processing of stress, afterwards. The profile sheet includes the amount of (1) downplaying, (2) defense against guilt, (3) distraction, (4) substitute satisfaction, (5) situation control, (6) reaction control, (7) positive self-instruction, (8) need for social support, (9) avoidance, (10) flight, (11) mental continuation, (12) resignation, and (13) self-blame. Resulting from this dialog, the clients choose goal-relevant strategies and look at all possibilities on how to use these strategies or a potential modification of them regarding goal attainment. For instance, the clients could identify a possible distraction from stress inducing situations as an important stress processing strategy and therefore create an action plan for preventive or future in-case use. At the end of this session, the clients should be able to summarize their findings and write them down as a support for goal attainment and future usage of their worked out personally fitting coping strategies.

As a work at home exercise for the next session the clients should be motivated to create an individual stress processing plan, which has been adapted from the action plan of the carrier-coaching concept by Braumandl et al. (2013). The clients have to list three concrete measures for improving their stress management and which they want to attain in the near future. They then have to write down precise next steps in order to achieve these measures. Moreover, they have to write down situative surrounding factors that are associated with the goal attainment. In addition, the clients describe the stress management coping strategies they want to apply. In a next step, the clients identify people that will support them and check their progress. The last aspect enables the clients to review what has already been successful and which parts of the goal attainment need further steps.

3.3 Third CBSM Coaching Session

In the third CBSM coaching session, the introduction and the self-reflection should be carried out in a similar manner as in the second session. The focus of this session should be on the completed individual stress processing plan. The possible solution- and emotion-focused coping mechanism, which were found to be relevant in past sessions, should be intensively discussed once again. In this session, it is of utmost importance to discuss and find precise action steps and adequate stress processing strategies as well as to adapt possible situational factors in a promotive way. The clients should be able to detect specific social support regarding the sub-goals. Moreover, all relevant and possible hindrances to goal attainment should be discussed and the clients are given support to identify personal counteractive strategies from their repertoire. When these steps are done, the coaching process should be then reviewed as a whole. The clients should be motivated to scale their goal attainment at the moment and to look forward to completing it. Moreover, they should draw their own conclusions or lessons learned over the course of the coaching process. According to the transactional stress model, this procedure supports coping as well as pacing and learning in accordance with reappraisal.

An overview of the three CBSM coaching sessions in regard to the transactional stress model is displayed in Fig. 1 (right side).

4 Case Study “Mr. Smith”

To illustrate the coaching concept, the concrete procedure is described using the following case: Mr. Smith is 36 years old and is working as a freelance technician in the IT sector and studying computer science part-time. He has been living with his wife for 4 years and is planning to renovate the house in the coming years. As part of his freelance job, Mr. Smith supports several customers, although if unforeseen problems arise he attends to them immediately, even though he may be busy with other work-related tasks or out of the office for work-related tasks. Meanwhile, he also sometimes receives additional telephone and email inquiries from new customers. He often forgets important details of the telephone inquiries or he is not able to find crucial notes afterward if he took them on the go. These circumstances create an additional workload concomitant with high subjective stress as he has to ask customers for specific information once again. This matter, among other things, has a negative effect on his leisure time and the relationship with his wife.

4.1 First Session of the Case Study

At the beginning of the first session of CBSM coaching, Mr. Smith describes his increased workload and decrease in his free time caused by interruptions at short notice by customer inquiries. These often lead to conflicts with his wife. In the past, Mr. Smith has read several time management books and tried to implement methods. However, these only resulted in short term success in particular areas – i.e. he designated specific days of the week for his work on customer projects, though after several weeks he stopped following this schedule and relapsed into his former pattern. To date the client has no experience with stress-related coaching or training. Following the coach’s question, as to what tangible benefit the client expects from the CBSM coaching, Mr. Smith describes his expectations to find a realizable concept for his daily routine at work, which he is able to adhere to over the long term and to be motivated by the coach. Mr. Smith wishes to be able to work more effectively and therefore reduce the perceived stress level. Regarding the above mentioned, the coach describes his/her general role in the coaching process and states that he/she will ask questions with the aim of improving the client’s viewpoint towards the stressors. With regard to the coach’s question, which aspects at work are already working in a positive way, the client states that he feels very competent in his area of expertise and is therefore able to find solutions to customer problems efficiently, which partly compensates for his problems in planning activities at work accurately. In addition, tasks and learning content for his studies are easily implemented, if he is able to find time to study.

His primary coaching goals correlate with the described coaching motives and were quoted on the application form for coaching participation and sorted by priority, as follows:

-

1.

scheduling – don’t get overwhelmed by everyday life and don’t get caught in a rat race

-

2.

reduce stress

In the following goal-definition process the client’s goals are discussed, formulated in the SMART way, and visualized. For this purpose, the coach introduces the intervention “miracle question” (deShazer 1988) and describes that this question may seem unusual at first but could be beneficial. The coach encourages Mr. Smith to imagine the following: “After we finish here, you go home tonight, watch TV, do your usual chores, etc. and then go to bed and to sleep. While you are sleeping, a miracle happens. The problems that you presented here have been solved, just like that. However, this happens while you are sleeping, so you cannot know that it has happened. As soon as you wake up in the morning, how will you go about discovering that this miracle has happened to you or how will your wife know that this miracle has happened to you? Please describe this fictitious day in as much detail as possible”.

Mr. Smith describes that he stays in bed for a short time before contemplating about the day ahead and finally gets up. At the same time he feels confident, reassured and joyous as he is looking forward to breakfast with his wife and he also knows that he has university courses in the morning. At work in the afternoon he has customer appointments and he even has additional time for potential customer inquiries. During breakfast his wife also acts joyous, as she perceives Mr. Smith as relaxed. Lacking of negative thoughts the client is able to show interest in his wife’s well-being and daily plan. At university his fellow students notice that Mr. Smith is more open and communicative, he shows involvement in group tasks in a very productive way. At the university he is also able to finish several other study-related tasks, which he is very proud of. Afterward he is able to eat dinner with friends and keep customer appointments, which run smoothly. His customers feel they are being treated in a professional manner and think he is well prepared. After that, he drives home and still has time left to work on customer inquiries or to prepare for his next appointments. He is happy and relieved since he thinks his day has been very productive. As a result his breathing is much calmer and smoother; he is happy that he can spend the rest of the evening with his wife. His wife smiles as he greets her.

The coach asks about a moment in the client’s past, which was similar to this fictitious day. Mr. Smith states that he had a similar feeling about a year ago when he tried to formulate a weekly schedule after he read a book about time management. He tried to stick to this schedule for a certain time but relapsed into his old habits. The coach begins to talk about the answers to the miracle question in detail and he connects them to the goals defined by the client in his application form. The coach then supports the client in setting his goals using the SMART method with goal specific questions. At first the coach addresses the feeling of confidence mentioned after the client gets up out of bed and asks how he perceives himself when he feels confident and secure and how this aspect could connect with the goal “scheduling”. The client describes that he is more flexible when he feels confident and therefore knows that he is able to manage his tasks at work more efficiently. It would be very important for him that he has easy access to the schedule for the upcoming day after he gets up out of bed in the morning. Following the question from the coach, what this schedule should contain in detail, in order for him to be able to fulfill his work obligations and obligations at home adopting his described feeling of confidence, the client states that he would need a daily checklist and list of daily appointments regarding his studies and work. Furthermore, it would be important for him to have enough free time between appointments, so he is not constantly running from one appointment to the next, or – formulated in a positive way – he would be able to calm down and regain energy.

The client observes that his two goals overlap and considers them to be consistent – scheduling would result in reduction of perceived stress. He would like to subsume these aspects of his goal under “better time management and scheduling”. The coach poses further questions so that the client is able to substantiate his scheduling plans (i.e., the included tasks, time frame). Mr. Smith describes that he would need a detailed weekly schedule, which he would draw up every weekend from a general monthly or annual schedule and also refer to new upcoming appointments. He likes to have his schedule at hand all the time.

In a further step, the coach supports the client to find key elements of goal-achievement whereupon Mr. Smith states that he would recognize it when he gets up in the morning and feels confident – with a feeling of calmness – when regarding his upcoming tasks and is happy to start the day. Moreover, he would have his weekly schedule at hand which he believes is absolutely necessary for a successful and sustainable time management. The client likes to work and study and is happy in his marriage as he has time to spend with his wife without thinking about work-related topics too much. Mr. Smith considers his goal “better time management and scheduling” to be realistic as he was able to implement a schedule to some extent in the past and wants to make an effort to achieve a sustained benefit. The client would like a draft of the schedule in no later than two weeks after the coaching session and based on this he would like to have improved his time management skills within six months.

Subsequently, the coach clarifies with the client in the context of a goal process evaluation where he perceives himself on a scale from 1 to 10 at the moment and what his goal status should be. Regarding his current status Mr. Smith rates himself currently on level 3 and defines his goal level as 9. As an answer to the question what needs to change in order to reach level 4, the client answers that he needs to prioritize his weekly tasks and appointments. The coach further asks what would change on the next levels reached from 5 to the goal level 9. In the end, Mr. Smith formulated the following goals for himself:

-

S (specific):

I would like to enhance my time management skills so that I am able to plan my appointments at work as efficiently as possible, so that I am able to complete them successfully and still have time and energy for unforeseen short-term tasks as well as for private life (wife, friends, hobbies, house renovation). Sub-goals are (a) prioritize job and studies duties and responsibilities as well as periods for stress reduction and prevention, (b) draw up weekly schedule of prioritized tasks, (c) establish more efficient workflow, and (d) take care of myself (health).

-

M (measurable):

I will have my weekly schedule at hand all the time. Furthermore, I will have time for private life at the weekends and on at least two evenings per week.

-

A (assignable):

I will reach my goals of getting up out of bed in the morning feeling confident, of having a balanced mindset as well as enjoying a happy marriage and maintaining existing friendships.

-

R (realistic):

My goal is realistic because for the first step I have sufficient time (two weeks) and will be able to optimize my schedule and time management capabilities to fully integrate it in my everyday life.

-

T (time-related):

First draft of my weekly schedule within two weeks at the latest as well as implemented optimized time management skills within six months.

In conclusion of the first session, Mr. Smith states that he has only reacted to the job-related requirements up to date and did not take time finding ways of being proactive. After the review of the coaching process and unanswered questions, the coach presented the task energy card (Braumandl et al. 2013; Weisweiler et al. 2012) as well as the stress processing questionnaire (SVF-78; Janke et al. 1985) to work on at home for the second session.

4.1.1 Reflection from the Coach’s Point of View

The client carries out several tasks at any one time in his everyday life, which he considers a positive aspect in order to be reachable by customers anytime. However, as a negative consequence he feels he is caught up in a rat race. He does not take time to reflect on his thoughts, feelings and alternative approaches for a better work-life balance between his freelance job, studies, marriage and friendships. The client’s summarized goal topic “better time management and scheduling” and the associated reduction of the perceived subjective stress level suits the process of the CBSM coaching because the aspects in this regard are being discussed in the third session (i.a., clarification of the term better time management, assessment of stressors and supportive factors, concrete action plan for goal attainment).

During the first session the concrete goal declaration, prioritization and scaling represent the main interventions. In this regard sub-goals and behavioral characteristics in connection with goal attainment are being developed together with the client. At first he names the areas which he chooses to work on (i.e., “scheduling – don’t get overrun by everyday life”) but is not able to specify them initially. The goal reformulation (i.e., SMART way of defining goals) as well as setting sub-goals in combination with goal visualization on cards and via goal-attainment scale support the client concerning this matter.

4.2 Second Session of the Case Study

First, the coach asks Mr. Smith about the current goal status. The client tells that after completing the tasks at home he thought about his goal and has already begun structuring and prioritizing his tasks and therefore estimates the goal status with 4. After the goal process evaluation the coach asks the client about the task energy card. The client states that he has a good overview of stressors and possible resources and that the stressors currently predominate his everyday life and drain energy. The coach is interested what precisely has become clearer for Mr. Smith. Although Mr. Smith’s studies and job have a lot of positive aspects (i.e., interesting topics, a lot of positive social contacts). Since last year, they are draining his energy, especially his freelance job. He notices his work flow is unstructured but does not know where to apply countermeasures. The coach asks Mr. Smith to what extent a working day would differ, if he had attained his goal. The client describes that he works focused on the planned tasks and projects and that there is also time left for dinner and breaks, which is not the case at the moment. The coach asks Mr. Smith what he would think about arranging dinner with a friend, after having attained his goal. The client replies that he would have planned free time for dinner so he could meet up with friends in a relaxed setting. Besides, he would know that he would not have to be afraid of short-term telephone calls. On request of the coach, Mr. Smith describes this aspect in more detail and states that he does not take time for dinner anymore as he may have to respond to customer inquiries on the telephone or via email, which he partly answers en route. As a consequence, it often happens that scheduled appointments have to be postponed. The coach asks Mr. Smith which findings are to deviate regarding his coaching goal. Mr. Smith states that this is a very important aspect and he needs to change this in order to create and follow a weekly schedule. Therefore, Mr. Smith likes to put his sub-goal (c) “establish more efficient workflow” in second place before his goal of putting together a schedule (previously sub-goal b).

The coach asks the client which options a (potential) customer has to contact him. Mr. Smith explains that he has a homepage with a description of his services and his contact details for potential customers. Existing customers prefer to contact him via telephone or email and are used to his prompt answers.

In addition, the coach and Mr. Smith talk about positive aspects which he can build on and which give him energy. He highlights his marriage as he receives unconditional support from his wife, even if he sometimes seems to be a bit absent in stressful times. They share many common interests (i.e., sports) and Mr. Smith considers this to be a good opportunity for achieving a work-life balance. Furthermore, his friends and hobbies are positive aspects and he has neglected these in some cases as of late. He perceives himself as qualified and motivated in work-related things but he wants to please everybody without caring for himself.

The next part of the second session consists of the discussion of the results of the stress processing questionnaire. For this purpose, the coach presents the profile of the different coping strategies to the client. Mr. Smith finds the highly pronounced coping response “mental continuation” particularly conspicuous as he perceives himself the same way in his everyday life. Regarding his coaching goal and previous thoughts, he identifies a correlation in the fact that he has to be available around the clock. In addition, he worries about days with a high workload in advance. He knows that this would be a starting point. Therefore, he would like to consider his options at home for the next session. Moreover, the client likes both coping strategies “distraction” and “substitute satisfaction” which will help him to reach his sub-goals (a) “stress reduction and prevention” and (d) “take care of myself” more effectively in the future. In the past, he would pursue his hobbies in order to relieve work-related stress. The perfect situation would currently be that he would be able to do sports at least once per working week as well as at the weekends (i.e., biking with his wife, climbing with friends). The client makes a note of these findings on his goal card. In addition, the client chooses “reaction control” and “positive self-instruction” as coping strategies. In day-to-day life, he considers himself to be able to control his reactions and use self-instruction. Accordingly, he is able to deal with single stressful events positively. As an insight regarding goal-attainment, he is certain that he shows perseverance in work-related areas. However, he does not like to be in stressful situations for long periods anymore – he wants to be able to enjoy a relaxed working environment most of the time due to better scheduling. The coach asks about other useful strategies and the client replies that he could use “situation control” which reflects aspects of his coaching goals, hence situational analysis, scheduling and implementation of problem-solving capabilities. The client seems to be reassured and states that he feels he is heading in the right direction.

After today’s findings, Mr. Smith believes he has moved forward one step and is on level 4.5. At the end of the session, they talk about an exercise to be carried out at home – drawing up an individual stress processing plan. The client is able to formulate up to three concrete measures for improving his stress management.

4.2.1 Reflection from the Coach’s Point of View

In the second session, the results of the energy card and the stress processing questionnaire are discussed. The client is able to categorize all relevant areas of everyday life as energy drainer or energy contributor. At the beginning of the coaching, he mentioned that he feels like he is in a rat race. During the ongoing coaching process, the client realizes that being available for customers all the time via telephone and email drains a lot of his energy. He states that this aspect prevents him from advancing in his goals so he would like to implement concrete steps as soon as possible. Through repeating asking and paraphrasing, the coach tries to give the client the opportunity to be as precise as possible when describing his situation. As there are energy draining aspects in the client’s situation, it is of importance to also demonstrate energizing areas of life. In this regard, the client considers his wife as a very important support, which motivates him to achieve his goals.

As the client realizes that freelancing is very stressful, the results of the stress processing questionnaire are a suitable tool to observe the professional situation in more detail. The client sees the stress response “mental continuation” as the key to his occupational problems he wants to work on. In the further reflection of the results of the stress processing questionnaire, the client is able to identify further coping strategies (e.g., distraction, substitute satisfaction, reaction control, positive self-instruction) that will help him to achieve his goal.

4.3 Third Session of the Case Study

When asked about the current goal status, Mr. Smith joyfully replies that he has, among other things, worked on the implementation of the weekly schedule so he estimates his goal-attainment at level 5. The coach asks Mr. Smith about his specific implementations in the last week. The client reports that he has made some straightforward adjustments, which he had not considered before. At first, customers receive an automated email stating that he will answer within 24 h, or sooner in an emergency. This relieved some pressure and he did not feel the urge to answer immediately. Furthermore, he has added hours when he is available for work-related telephone calls to his website.

Following the invitation from the coach to present his elaboration on the individual stress processing plan, Mr. Smith mentions his first measure, namely the improvement of communication with customers. Concerning this, he plans to upgrade his website with a system for customer inquiries. The coach asks which information would be important for customers and for himself. Mr. Smith sees a benefit for the customers, as they would be able to send him an inquiry anytime in a straightforward way. The automation of his services will be personally beneficial as most telephone calls are not necessary. Moreover, the notes for the inquiries are created automatically and correctly. The coach asks the client how the inquiries will be preprocessed so that he is able to use them in an efficient way. Mr. Smith states that he could categorize and prioritize them automatically in a task list. The coach wonders which aspects would be important for customers so that they would use this system. Mr. Smith observes that many customers have small inquiries and send emails but they do not receive an automated completion status. With such a system, it would be easy to send status updates to the customers. As the system is very straightforward, it would be easy for customers to use. Mr. Smith considers the implementation as very realistic as he is able to program most of it himself and if he needs support, he could ask a fellow student. Regarding the preparation of his weekly schedule, Mr. Smith has included his lectures at the university, studying periods as well as time for customer appointments and processing inquiries from home. He also added sufficient free time, which will act as a buffer between appointments. When asked once again about the current goal status, Mr. Smith evaluates that he is on level 5.5. Afterwards further steps were discussed which would be necessary for further goal-attainment. As support, the client mentions his wife who is proud of him and assures him every day.

Finally, the coach and client summarize the coaching process. Mr. Smith is surprised that he uses a problem-oriented approach in computer sciences. However, he has not paid enough attention to adopting this approach to cope with problems in everyday life. He is very motivated to continue working on his goal and finds it very realistic to implement the weekly schedule in the upcoming week and that he will notice improvements in work-life balance in the next months.

4.3.1 Reflection from the Coach’s Point of View

During the third session, the task of creating an individual stress processing plan is discussed as the client has indeed formulated all relevant aspects regarding goal attainment and defined important stress processing strategies and energy boosters but hasn’t elaborated specific steps fully. As a specific step, the client names the implementation of a system for customer inquiries. As the system will have positive effects for both customers and the client, the coach found it important that the client is able to express his own needs as well as customer needs in detail. To consolidate the upcoming steps, regarding goal attainment, the client finally discusses them in as much detail as possible. Furthermore, the client is able to find potential support in case of expected setbacks.

5 Coaching Evaluation

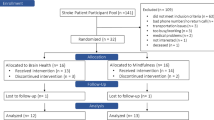

The coaching concept described above has already been applied to enable an assessment of the effectiveness by Junker et al. (2020). In a randomized controlled field study, undergraduates, who received the CBSM coaching (n = 24) were compared to a control group (n = 20) receiving no additional intervention – they just formulated stress-related goals based on the written instruction “Please formulate up to three stress-related goals which you like to achieve in the future”. By selecting goals in both groups (CBSM coaching group as well as control group), it was possible to investigate to what extent the goal achievement in the CBSM coaching group differed from the control group. “Coaches were master’s students in psychology who had successfully completed a professionally supervised 1‑year coaching training” (Junker et al. 2020, p. 7; for educational concept see Braumandl et al. 2013). In the first part of the training program, experienced coaches provided students with theoretical information and practical training on coaching-specific skills, for example, questioning techniques to facilitate clients’ goal attainment and self-reflection effectively. Training exercises and the following peer-coaching sessions addressed issues relating to career planning, such as identification of strengths and potentials, specification of resources and competences, shaping values and meaning, and the development of action plans. The second part of the training program involved the practical application of coaching skills in client coaching supervised by professionally trained supervisors. To ensure consistency in the study procedure, Junker et al. (2020) used guidelines to instruct coaches about the content and structure of each coaching session.

The authors found that both CBSM coaching and goal formulation had led to a significant increase in goal attainment that was maintained at a 4-week follow-up assessment. However, the CBSM coaching was superior in affecting participants’ cognitive stress appraisal positively and in leading to reduced chronic stress levels four weeks after the intervention in comparison to the control group. They could further show that the reduction of chronic stress was mediated by the change in participants’ cognitive stress appraisal. Thus, the CBSM coaching appears to be effective in helping individuals to develop strategies to deal with stress, while also remaining focused on relevant goals as expected in advance. These results are in accord with available evidence on the impact of stress management programs, suggesting that dyadic interventions that utilize a cognitive-behavioral approach have the potential to achieve meaningful change (Richardson and Rothstein 2008; van der Klink et al. 2001; Vanhove et al. 2016).

However, an important limitation of the described study is that the observed findings were based on an undergraduate sample (Junker et al. 2020). One could argue that the study sample may be sufficiently representative as there are relevant similarities between undergraduate students and employees in terms of the exposure to specific stressors (Gadzella 1994; Johnson et al. 2005). Accordingly, there is some indication that using student-recruited samples in organizational research does not diminish the practical conclusions that can be drawn from the findings (Wheeler et al. 2014). Moreover, there is some empirical support that suggests that various populations in different industries benefitted from cognitive-behavioral coaching. For example, providing additional coaching sessions with a focus on coping with psychosocial work stressors for nurses suffering from physical symptoms (i.e., shoulder, neck, or back pain) resulted in greater and sustainable improvements in pain severity and the ability to meet physical work demands compared to standard physiotherapy alone (Becker et al. 2017). Moreover, coaching was shown to reduce work-related stress levels of bank managers (David et al. 2016; Dippenaar and Schaap 2017), leaders from the healthcare sector (Grant et al. 2009, 2017), teaching professionals (Ogbuanya et al. 2017), rural general practitioners (Gardiner et al. 2013), physicians (Schneider et al. 2014) and employees and workers from different sectors (Duijts et al. 2008; Ladegård 2011; Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2017).

Independent of the question of generalization, further research is also necessary for the questions of which target groups particularly benefit from this approach. We argue that determining personal characteristics and abilities could yield useful information on who might benefit most from stress management coaching. This would be in accord with the fact that the impact of coaching may greatly depend on the specific individual in a specific context (Passmore and Fillery-Travis 2011). For instance, individuals with positive core self-evaluations, that is, the constructive view of oneself that is composed of self-efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control and emotional stability (Judge et al. 1997), were found to perceive fewer stressors and engage in less maladaptive coping strategies (Kammeyer-Mueller et al. 2009). Research findings suggest that developmental practices such as coaching have the potential to buffer the detrimental consequences of such destructive self-appraisals (Morris et al. 2013) and thus, future research should explore if coaching might be an effective approach to enhancing the capacity for adaptive response to stressful situations of employees with low core-self evaluations. Integrating client characteristics in stress management coaching research will surely provide relevant considerations for efficient intervention development and implementation in organizational settings, as such studies enhance knowledge on the specific target group’s needs.

6 Conclusion

The CBSM coaching concept presented in this paper offers a useful framework for coaches who want to support their clients in successfully managing stress. The conception of the coaching is based on an established theory – namely the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). All the exercises that are given to the clients are also in line with the theoretical assumptions of the underlying stress theory. This offers the opportunity to adapt the exercises, if needed guided by theory and not just by practical considerations. The directly presented exercises are especially useful for coaching newcomers who are not as confident as more experienced ones. By newcomers, we mean coaches who have undergone a coaching training, as within the evaluation study conducted by Junker et al. (2020), and have therefore acquired basic coaching knowledge and coaching skills, but who still have little coaching experience with clients. However, experienced coaches may also profit from the use of the concept as they can enrich it with any action that is also in line with the theoretical assumptions of the grounded theory. Presenting more such theory-based coaching concepts could therefore help connect research with practice. Such a way of working will be enriching for both researchers and practitioners and could thus help in closing the gap which sometimes exists between their approaches.

References

Becker, A., Angerer, P., & Muller, A. (2017). The prevention of musculoskeletal complaints: a randomized controlled trial on additional effects of a work-related psychosocial coaching intervention compared to physiotherapy alone. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 90(4), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-017-1202-6.

Braumandl, I., Amberger, B., Falkenberg, F., Kauffeld, S. (2013). Coachen mit Struktur – Konzeptcoaching. Ausbildung zum Coach für Karriere- und Lebensplanung (CoBeCe). Konzept, Theorie und Forschungsresultate. [Coaching with structure – Concept-coaching. Training to become a coach for career- and life-planning. Concept, theory, and research results]. In R. Wegener, A. Fritze, M. Loebbert (Hrsg.), Coaching-Praxisfelder. Forschung und Praxis im Dialog [Coaching practice areas. Research and practice in dialogue] (S. 73–83). Wiesbaden: Springer.

David, O. A., Ionicioiu, I., Imbăruş, A. C., & Sava, F. A. (2016). Coaching banking managers through the financial crisis: effects on stress, resilience, and performance. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-016-0244-0.

deShazer, S. (1988). Clues: Investigating Solutions in Brief Therapy. New York: Norton.

Dippenaar, M., & Schaap, P. (2017). The impact of coaching on the emotional and social intelligence competencies of leaders. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 20(1), a1460. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1460.

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management review, 70(11), 35–36.

Duijts, S. F., Kant, I., van den Brandt, P. A., & Swaen, G. M. (2008). Effectiveness of a preventive coaching intervention for employees at risk for sickness absence due to psychosocial health complaints: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Environ Med, 50(7), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181651584.

EU-OSHA – European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2014). Calculating the costs of work-related stress and psychosocial risks. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/calculating-cost-work-related-stress-and-psychosocial-risks/view. Accessed June 20, 2021.

Gadzella, B. M. (1994). Student-life stress inventory: identification of and reactions to stressors. Psychological Reports, 74(2), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.74.2.395.

Gardiner, M., Kearns, H., & Tiggemann, M. (2013). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural coaching in improving the well-being and retention of rural general practitioners. Aust J Rural Health, 21(3), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12033.

Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 227–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00113.x.

Grant, A. M. (2014). The efficacy of executive coaching in times of organisational change. Journal of Change Management, 14(2), 258–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.805159.

Grant, A. M., Curtayne, L., & Burton, G. (2009). Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: a randomised controlled study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902992456.

Grant, A. M., Studholme, I., Verma, R., Kirkwood, L., Paton, B., & O’Connor, S. (2017). The impact of leadership coaching in an Australian healthcare setting. J Health Organ Manag, 31(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-09-2016-0187.

Green, S., Grant, A. M., & Rynsaardt, J. (2007). Evidence-based life coaching for senior high school students: building hardiness and hope. Coaching Researched: A Coaching Psychology Reader. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119656913.ch13.

Greif, S. (2016). Wie wirksam ist Coaching? Ein umfassendes Evaluationsmodell für Praxis und Forschung [How effective is coaching? An evaluation model for practice and research]. In R. Wegener, M. Loebbert & A. Fritze (Eds.), Coaching-Praxisfelder. Forschung und Praxis im Dialog [Coaching practice areas. Research and practice in dialogue] (pp. 161–182). Heidelberg: Springer.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488.

Halkos, G., & Bousinakis, D. (2010). The effect of stress and satisfaction on productivity. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 59(5), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401011052869.

Hassard, J., Teoh, K. R. H., Visockaite, G., Dewe, P., & Cox, T. (2017). The cost of work-related stress to society: a systematic review. J Occup Health Psychol, 23(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000069.

Janke, W., Erdmann, G., & Kallus, W. (1985). Stressverarbeitungsfragebogen (SVF) [stress processing questionaire]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., & Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940510579803.

Jones, R. J., Woods, S. A., & Guillaume, Y. (2014). The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12119.

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., & Durham, C. C. (1997). The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: a core evaluations approach. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 151–188). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Junker, S., Pömmer, M., & Traut-Mattausch, E. (2020). The impact of cognitive-behavioural stress management coaching on changes in cognitive appraisal and the stress response: a field experiment. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2020.1831563.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Judge, T. A., & Scott, B. A. (2009). The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. J Appl Psychol, 94(1), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013214.

van der Klink, J. J. L., Blonk, R. W. B., Schene, A. H., & van Dijk, F. J. H. (2001). The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 270–276.

Ladegård, G. (2011). Stress management through workplace coaching: the impact of learning experiences. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 9(1), 29–43.

Lauterbach, M. (2008). Einführung in das systemische Gesundheitscoaching [Introduction to systematic health coaching]. Heidelberg: Carl-Auer-Verlag.

Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological inquiry, 1(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0101_1.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Linden, D. V. D., Keijsers, G. P. J., Eling, P., & Schaijk, R. V. (2005). Work stress and attentional difficulties: an initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work & Stress, 19(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500065275.

Losch, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., Mühlberger, M. D., & Jonas, E. (2016). Comparing the effectiveness of individual coaching, self-coaching, and group training: how leadership makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(629), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00629.

Michie, S., & Williams, S. (2003). Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review. Occup Environ Med, 60(1), 3–9.

Milner, A., Witt, K., LaMontagne, A. D., & Niedhammer, I. (2018). Psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Occup Environ Med, 75(4), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104531.

Morris, M. L., Messal, C. B., & Meriac, J. P. (2013). Core self-evaluation and goal orientation: understanding work stress. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 24(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21151.

Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Schoutens, A. M. C., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W., & Sluiter, J. K. (2017). Evaluation of a randomized controlled trial on the effect on return to work with coaching combined with light therapy and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy for workers with work-related chronic stress. BMC Public Health, 17, 761. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4720-y.

Nixon, A. E., Mazzola, J. J., Bauer, J., Krueger, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2011). Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work & Stress, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.569175.

Ogbuanya, T. C., Eseadi, C., Orji, C. T., Ohanu, I. B., Bakare, J., & Ede, M. O. (2017). Effects of rational emotive behavior coaching on occupational stress and work ability among electronics workshop instructors in Nigeria. Medicine (Baltimore), 96(19), e6891. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006891.

Palmer, S., Tubbs, I., & Whybrow, A. (2003). Health coaching to facilitate the promotion of healthy behaviour and achievement of health-related goals. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 41(3), 91–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2003.10806231.

Passmore, J., & Fillery-Travis, A. (2011). A critical review of executive coaching research: a decade of progress and what’s to come. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 4(2), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2011.596484.

Richardson, K. M., & Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol, 13(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69.

Schneider, S., Kingsolver, K., & Rosdahl, J. (2014). Physician coaching to enhance well-being: a qualitative analysis of a pilot intervention. Explore (NY), 10(6), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2014.08.007.

Shader, K., Broome, M., Broome, C., West, M., & Nash, M. (2001). Factors influencing satisfaction and anticipated turnover for nurses in an academic medical centre. Journal of Nursing Administration, 31(4), 210–216.

Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., & van Vianen, A. E. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.837499.

Transactional Model of Stress and Coping – Richard Lazarus.svg (2021). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Transactional_Model_of_Stress_and_Coping_-_Richard_Lazarus.svg (Created 16 Oct 2016). Accessed June 24, 2021.

Vanhove, A. J., Herian, M. N., Perez, A. L. U., Harms, P. D., & Lester, P. B. (2016). Can resilience be developed at work? A meta-analytic review of resilience-building programme effectiveness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(2), 278–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12123.

Weisweiler, S., Dirscherl, B., & Braumandl, I. (2012). Zeit- und Selbstmanagement: Ein Trainingsmanual – Module, Methoden, Materialien für Training und Coaching. [Time and self-management: a training manual – modules, methods, materials for training and coaching]. Heidelberg: Springer.

Wheeler, A. R., Shanine, K. K., Leon, M. R., & Whitman, M. V. (2014). Student-recruited samples in organizational research: a review, analysis, and guidelines for future research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12042.

Zanchetta, M., Junker, S., Wolf, A.-M., & Traut-Mattausch, E. (2020). “Overcoming the fear that haunts your success” – the effectiveness of interventions for reducing the impostor phenomenon. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(405), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00405.

Acknowledgements

We thank Isobel Klier for her help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

E. Traut-Mattausch, M. Zanchetta and M. Pömmer declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Traut-Mattausch, E., Zanchetta, M. & Pömmer, M. A Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management Coaching. Coaching Theor. Prax. 7, 69–80 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1365/s40896-021-00056-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1365/s40896-021-00056-2