Abstract

Background

Owing to multimodal treatment and complex surgery, locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) exerts a large healthcare burden. Watch and wait (W&W) may be cost saving by removing the need for surgery and inpatient care. This systematic review seeks to identify the economic impact of W&W, compared with standard care, in patients achieving a complete clinical response (cCR) following neoadjuvant therapy for LARC.

Methods

The PubMed, OVID Medline, OVID Embase, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases were systematically searched from inception to 26 April 2024. All economic evaluations (EEs) that compared W&W with standard care were included. Reporting and methodological quality was assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS), BMJ and Philips checklists. Narrative synthesis was performed. Primary and secondary outcomes were (incremental) cost-effectiveness ratios and the net financial cost.

Results

Of 1548 studies identified, 27 were assessed for full-text eligibility and 12 studies from eight countries (2016–2024) were included. Seven cost-effectiveness analyses (complete EEs) and five cost analyses (partial EEs) utilized model-based (n = 7) or trial-based (n = 5) analytics with significant variations in methodological design and reporting quality. W&W showed consistent cost effectiveness (n = 7) and cost saving (n = 12) compared with surgery from third-party payer and patient perspectives. Critical parameters identified by uncertainty analysis were rates of local and distant recurrence in W&W, salvage surgery, perioperative mortality and utilities assigned to W&W and surgery.

Conclusion

Despite heterogenous methodological design and reporting quality, W&W is likely to be cost effective and cost saving compared with standard care following cCR in LARC.

Clinical Trials Registration PROSPERO CRD42024513874.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rectal cancer exerts a large healthcare burden globally, ranking as one of the highest in prevalence and mortality worldwide.1 Standard management of locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) involves neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision (TME).2 Some patients achieve a complete clinical response (cCR) post-neoadjuvant therapy, where no tumor is detectable on clinical examination, endoscopy and imaging.3 In such cases, TME may expose patients to perioperative morbidity, mortality, and potential long-term sexual, urinary and bowel dysfunction and be unnecessary.4,5 Non-operative management or ‘watch and wait’ (W&W) offers comparable disease-free survival (DFS) rates6,7,8,9,10,11 and, owing to avoidance of surgery, has been associated with improved quality of life (QoL) compared with TME.12,13 Despite the 20–25% risk of local regrowth in W&W that necessitates intensive surveillance,10,11 successful surgical salvage is possible in over 90% of cases.7,11

Total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT), combining neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) and upfront chemotherapy, has demonstrated improved rates of DFS, cCR, and pathological complete response (pCR) in LARC.14,15,16 Accordingly, TNT use has increased dramatically in recent years.17 Given the increasing rates of cCR, risks of surgery, and similar W&W DFS, it is possible that more patients and clinicians will consider W&W as the primary treatment option.

Global treatment costs of colorectal cancer are projected to surpass billions of US dollars and a co-ordinated international effort to mitigate the rising cost is warranted.18 LARC management is expensive given frequent use of combination treatment modalities and complex surgery.19 Surgery is associated with significant costs, attributable to inpatient hospital stay, surgical supplies, operating theatre expenses, and high overall complication rates.20 By avoiding surgery and inpatient hospital care, W&W has the potential to be a substantially cost-effective and cost-saving intervention.21,22,23 However, to capture recurrences early, W&W protocols involve rigorous surveillance through frequent multimodal imaging, blood tests, endoscopies and office visits, which adds to the financial burden.

The objective of this systematic review was to identify the economic impact of W&W, versus standard of care, in patients who have achieved cCR following neoadjuvant therapy for LARC.

Methods

This systematic review of healthcare economic evaluations (EEs) followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA)24 and Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) guidelines,25 and was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024513874).

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants were adult (>16 years) primary LARC patients who received neoadjuvant therapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both). The intervention studied was W&W versus standard of care (TME with or without adjuvant chemotherapy). The primary outcome was the (incremental) cost-effectiveness ratio, and secondary outcomes were the net financial costs of the interventions.

Complete (cost-effective analysis, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis, and cost-minimization analysis) and partial (cost analysis) EEs with varying healthcare perspectives, time horizons, settings, and discount rates were eligible. Exclusion criteria included pediatric population, malignancy proximal to the rectosigmoid junction, distant metastasis, or recurrent LARC. Case reports, editorials, letters, systematic reviews, comments, mini-reviews, book chapters and conference abstracts were excluded.

Search Strategy

The PubMed, OVID Embase, OVID Medline, and Cochrane Library CENTRAL databases were searched from inception to 21 February 2024, and updated on 26 April 2024, for studies of any design, in any setting, without language or publication restrictions. Keywords were related to ‘rectal neoplasms’, ‘watchful waiting’, ‘organ preservation’, ‘economics’, and ‘cost’. The full search strategy was developed with input from a database librarian (electronic supplementary material [ESM] 1). Supplementary searching included reviewing reference lists of included articles, consulting subject experts, and screening grey literature.

Study Selection

Studies were screened using the Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). After duplicate removal, two reviewers independently screened all titles, abstracts, and full texts, resolving disagreements by consensus, arbitrated by a third reviewer.

Data Extraction

Baseline study characteristics and outcome data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a standardized form, resolving discrepancies by consensus, arbitrated by a third reviewer. Study characteristics included author details, publication year, country, healthcare setting, study period, type of EE, analytical approach, study perspective, time horizon, discount rate, population and intervention characteristics. Outcome data extracted were the mean costs, effectiveness, and uncertainty analysis.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of trial-based EEs was examined using the British Medical Journal (BMJ) checklist,26 which contains 35 items evaluating study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation. Model-based EEs were assessed using the Philips checklist,27 which consists of 58-items assessing model structure, data, and consistency. Reporting of EEs were evaluated using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) 2022 checklist, which includes 28 items aimed to standardize and enhance transparency in reporting.28

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological and reporting quality, resolving disagreements by consensus, arbitrated by a third reviewer. Each item for the CHEERS, BMJ, and Philips checklists was recorded as ‘yes’ (1 point), ‘no’ (0 points), or ‘not applicable’ to assess completeness. As there are no validated scoring metrics for these checklists, grading systems or percentage cut-offs were not used.26,27,28,29

Data Analysis

Due to jurisdiction-specific factors such as location, healthcare system, time horizon, and perspective, there can be considerable heterogeneity in outcomes of EEs. Guidelines discourage pooling of primary outcomes when studies vary in their clinical setting or methodology,30 precluding meta-analysis due to these inherent limitations. Instead, synthesis of economic evidence followed established guidelines, employing structured narrative synthesis to present study characteristics, methodological quality, and outcomes.25 For review purposes, published costs were adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity using a validated online calculator (https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/) using OECD data, targeting 2022 Australian dollars (AUS$) when reference data were available.31

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed by searching the grey literature, conference abstracts not proceeding to publication, analysis of sponsorship in included studies and outcome differences, and presence and results of uncertainty analysis.30

Results

Study Selection

Of 1548 articles retrieved, 519 duplicates were removed; of the 1029 articles screened by title and abstract, 1002 were irrelevant. Twenty-seven articles proceeded to full-text review and 9 met the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded due to wrong study design (n = 17) and wrong patient population (n = 1). Supplemental searches identified three more studies, resulting in a total of 12 studies for inclusion in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Economic Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Studies were published between 2016 and 2024 and originated from eight countries: United States,22,23 The Netherlands,32,33 Spain,34,35 Germany,36,37 Australia,38 New Zealand,39 United Kingdom,21 and Japan.40 Seven studies were cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA),21,22,23,32,34,35,37 while the remainder were cost analyses (CA).33,36,38,39,40 Seven studies adopted a model-based approach.21,22,23,32,34,36,37

Comparators to W&W were abdominoperineal resection (APR) in three studies,36,37,40 APR and low anterior resection (LAR) in three studies,22,23,38 and unspecified in the remaining studies. Rodriguez-Pascual et al. compared W&W with standard and robotic resection.34 In the article by Wurschi et al., the W&W cohort received TNT whereas the surgical comparator received nCRT.37 For the remainder, both cohorts received nCRT. Three studies specified low rectal cancer requiring APR,36,37,40 while the remaining studies investigated rectal cancer of any height. In all studies, only patients with cCR were offered W&W, whereas patients undergoing surgery may have achieved pCR,35,38,39 incomplete clinical response,32,33,37,40 or cCR,21,22,23,34,36 potentially biasing the outcomes.

Methodological Details

Table 2 summarizes the methodological details of the included studies. Eleven studies adopted a hospital or third-party payer (TPP) perspective,21,22,23,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40 while Wurschi et al. adopted a patient perspective.37 When unspecified, perspective was inferred from costing information. Various time horizons were explored: 2 years,33 3 years,35,38 5 years,23,36,37,39,40 and lifetime.21,22,32,34 Costs and effects were discounted in seven studies, ranging from 1.5 to 4% depending on study jurisdiction.21,22,23,32,34,36,40 Model types included decision tree,36 Markov,22,23,32,34,37 or both.21

Resource use in trial-based EEs was estimated from patient records and local institutional policies. Transition probabilities in model-based EEs were sourced from published literature, population statistics, practice guidelines, clinical trials, and institutional databases. Cost estimates reflected jurisdiction-specific payment systems, except in one Spanish study, where costs were derived from the US.34 Utilities were predominantly sourced from published literature and also institutional databases in two studies34,35 and expert elicitation in one study.32 Detailed data sources for modeling studies are provided in Table 3.

Model-based uncertainty was assessed with deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) to investigate parameter uncertainty in six studies,21,22,23,32,36,37 probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to investigate simultaneous joint parameter uncertainty in four studies,21,22,23,34 and scenario analysis to investigate model assumptions in three studies.21,23,32 Subgroup analyses were conducted in three studies to investigate heterogeneity.21,35,37 Three trial-based EEs reported statistical analysis: standard deviations,33 p-values,39 or both.35

Quality Assessment

Studies were heterogenous in reporting and methodological quality. Table 2 displays the assessment for each study. The completeness of reporting ranged between 48 and 86% using the CHEERS 2022 checklist. Figure 2 demonstrates the proportion of studies that satisfied each item in the checklist. Completeness for the BMJ checklist for trial-based EEs was between 55 and 82%, and between 60 and 87% for the Philips checklist for model-based EEs. The full quality assessment matrix for each study is displayed in ESM 2.

Cost Effectiveness

Seven studies (six modeling, one trial) evaluated cost effectiveness.21,22,23,32,34,35,37 Outcomes are summarized in Table 4 for model-based EEs and in Table 5 for trial-based EEs. Across time horizons of 3 years to lifetime, all studies consistently identified W&W to be dominant over surgical comparators, offering lower costs and higher quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) from both TPP21,22,23,32,34,35 and patient perspectives.37 Standardized incremental costs of W&W ranged from AUS$1141 to AUS$192,145 (3–50%) less per patient (i.e. cost saving) from the TPP perspective and AUS$3203 (25%) less from the patient perspective. The incremental QALYs associated with W&W ranged from 0.089 to 2.03 more QALYs than surgery.

In US studies over 5-year and lifetime horizons, W&W demonstrated 40–50% lower costs and superior QALY compared with both LAR and APR.22,23 Similarly, Spanish studies over 3-year and lifetime horizons demonstrated W&W dominance over surgical resection, including robotic resection in one study.34,35 Ferri et al. raised methodological concern by appearing to apply utilities derived from Short-Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaires at 12 months across 3 years without elaboration, potentially affecting the reliability of QALY estimates.35 Rodriguez-Pascual et al. used US costing estimates, potentially limiting applicability to the Spanish jurisdiction.34 Dutch and UK studies found W&W to be dominant over surgery over a lifetime,21,32 despite challenges in obtaining appropriate W&W utilities due to the lack of published literature. Hendriks relied on expert elicitation at the author’s institution32 and Rao et al. relied on proxy data from prostate cancer literature.21

One German study provided the only patient perspective, demonstrating W&W dominance over APR across a 5-year time horizon.37 However, W&W patients received TNT versus nCRT in the APR comparator, potentially limiting applicability as this may not reflect clinical practice.

Cost

Five studies performed CA comparing W&W with surgery; four trial-based EEs33,38,39,40 and one model-based EE.36 All were performed from TPP or hospital perspectives, with time horizons ranging from 2 to 5 years. W&W consistently showed lower costs compared with surgery across all studies. Standardized cost differences ranged from AUS$17,945 to AUS$37,010 (40–61% less costly).

A Dutch study with a 2-year time horizon demonstrated mean hospital costs of AUS$15,176 (95% confidence interval [CI] $13,895–16,456) for W&W and AUS$38,675 (95% CI $35,291–42,060) for surgery, translating to an AUS$23,499 (61%) cost reduction per patient.33 Similarly, a small (n = 10) trial-based Australian study with a 3-year time horizon showed mean costs of AUS$55,315 for W&W and AUS$92,325 for surgery, resulting in an AUS$37,010 (40%) cost reduction per patient.38

Three studies compared costs with a 5-year time horizon. In Japan, mean costs were AUS$18,858 for W&W and AUS$36,803 for APR, with a cost saving of AUS$17,945 (49%) per patient.40 In New Zealand, mean costs were NZ$47,906 for W&W and NZ$70,760 for surgery, resulting in a NZ$22,854 (32%) cost saving per patient.39 This was the only study to factor in neoadjuvant treatment costs, potentially increasing net financial costs compared with other studies. A German decision tree model found W&W costs were €6344 and APR costs were €14,511, saving €8167 (56%) per patient.36

The varying approaches used with respect to time horizon, discounting, and management of inflation limited the value of across-study comparisons of absolute and incremental costs.

Heterogeneity

Three studies performed subgroup analyses. Ferri et al. found greater cost savings with the W&W approach for low rectal tumors compared with medium-high rectal tumors, likely due to increased surgical complexity and risk of post-surgical complications.35 Wurschi et al. examined patient costs and found employed W&W patients had twice the cost saving compared with retired patients, likely due to reduced productivity losses.37 Rao et al. examined three cohorts: healthy 60- and 80-year-old males, and comorbid 80-year-old males, finding W&W dominant across all cohorts.21

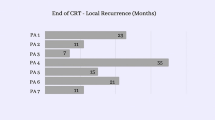

Uncertainty

Ten studies conducted statistical or sensitivity analysis to address uncertainty.21,22,23,32,33,34,35,36,37,39 DSA across six studies demonstrated key parameters impacting outcomes were rates of local regrowth21,22,23 and distant metastasis following W&W,22,23 salvage surgery,22 perioperative mortality21 and utilities for W&W and surgical comparators.21,22,23,32,37 Doubling W&W costs or decreasing surgical costs by 90% could have altered outcomes in two studies.36,37

PSA was performed in four studies.21,22,23,34 US studies demonstrated W&W to be dominant over 5-year and lifetime horizons in almost all simulations.22,23 Rao et al. demonstrated W&W’s dominance with high certainty (>70%), with increasing certainty among older and comorbid patients.21 Rodriguez-Pascual et al. showed W&W to be cost saving in almost all simulations and mostly increasing QALYs when compared with standard and robotic resection (87% and 55% of simulations, respectively), however there were concerns regarding costing data and utility acquisition methods.34

Three model-based studies performed scenario analyses, examining different patient populations,32 adjuvant chemotherapy timings,23 and surveillance protocols,21 all showing W&W dominance in all scenarios examined. Trial-based EEs demonstrated statistically significant results, with p-values <0.05 in two studies35,39 and non-overlap of calculated confidence intervals in one study.33

Publication Bias

Searching of the grey literature and conference abstracts not proceeding to publication did not reveal any undiscovered articles. Analysis of sponsorship demonstrated three articles with academic affiliations,22,35,36 two with government affiliations,21,23 and one with industry affiliation.22 There were no differences in outcome based on sponsorship, and all sponsored articles included appropriate uncertainty analysis.

Discussion

EE is crucial in the assessment of new health technologies and health protocol implementation, enabling decision makers and policy developers to review the impact of interventions and allocate scarce healthcare resources efficiently. In this first systematic review of the global economic impact of W&W, 12 eligible studies of varying reporting quality and methodological designs were identified. Seven CEAs and five CAs all reported improved cost-effectiveness and cost-saving associated with W&W across a variety of time horizons and perspectives.

A key strength of this review was the comprehensive search strategy and broad eligibility criteria facilitating inclusion of different types of EEs globally. A consistent direction of effect favoring W&W as the dominant strategy suggests that the conclusions could be applicable internationally across heterogeneous health systems and patient populations. Multidimensional assessment of methodological and reporting quality allowed recognition and highlighting of high-quality EEs.

Of the 12 studies, 11 reported costs from TPP or hospital perspectives, while only one utilized the patient perspective. None comprehensively assessed societal costs, including indirect and intangible costs, such as productivity loss associated with frequent appointments during intensive W&W surveillance, or the psychological burden associated with the uncertainty of cancer prognosis. Additionally, none assessed implementation and maintenance costs of W&W pathways that may require significant coordination of the patient’s clinical journey, frequently necessitating a dedicated cancer care coordinator.41 Further research should explore the impact of a broader perspective and of broader cost considerations for W&W on its cost effectiveness. However, as two studies indicated that large changes in costs would be required to alter the conclusion of cost effectiveness of W&W versus surgery, even accounting for a more costly W&W pathway may not alter the dominance of W&W.

Considering the applicability of the results of this review to current LARC management is important. Neoadjuvant therapy included TNT in only one study.37 Given current practice recommendations and trends towards adoption of TNT,2,17 with more intensive upfront chemotherapy use and higher cCR rates, it remains unclear if the cost effectiveness of W&W will persist in TNT patient populations. In the single study utilizing TNT prior to W&W, the surgical comparator received nCRT, limiting its relevance to real-world practice, where clinicians are deciding on W&W for patients treated with TNT alone.37 Model-based CEAs examining TNT versus nCRT followed by TME from a TPP perspective found TNT was the dominant strategy over a 5-year time horizon,42,43 but did not explore the impact of W&W policies in the cohort. Finally, trial-based EE comparators in this review varied, and given incomplete clinical response is associated with poorer oncological outcomes compared with cCR, comparisons of cCR in W&W to incomplete clinical response in surgery may have biased results towards W&W. Additionally, comparison of pCR in surgery with cCR in W&W may have biased results towards surgery. Given it may be impractical or impossible to randomize patients to W&W versus surgery, high-quality prospective cohort data with standardized comparators are needed to allow accurate decision making.

This systematic review has limitations. First, the jurisdiction-specific nature of EEs results in inherent heterogeneity. This trade-off between local applicability and global generalizability precludes formal meta-analysis. As such, results were narratively synthesized, with a consistent direction of effect favoring W&W across all evaluations. Methodological and reporting quality varied significantly, with several studies failing to follow the majority of reporting guidelines.28 Future research should prioritize adherence to minimum reporting standards and good practice guidelines to improve quality, standardization, and transparency.

A limitation of summarizing outcomes of model-based EEs is that many used the same sources, or other model-based EEs, for their input parameters—namely transition probabilities and health state utilities. Given analogous inputs, it may not be surprising that the results themselves tended towards similar outcomes. Therefore, if an evidence source that underpins multiple EEs is inaccurate, there is concern that the multiplicity of analyses may amplify an erroneous conclusion rather than provide independent verification, reinforcing the need for thorough critical appraisal of the underlying input sources in addition to the economic modeling methodology. Moreover, due to limited literature, some studies used health utility data derived from prostate cancer literature or expert opinions, potentially introducing bias. Future research focusing on patient-reported outcomes and QoL would improve the accuracy of these decision-making models. Nevertheless, the identification of model structure and relevant input parameters may inform future model development.

In half of the model-based CEAs, DSA suggested potential outcome differences with varying local and distant recurrence rates post W&W. Although the thresholds exceeded published rates, long-term prospective follow-up data are limited. Additionally, recent literature suggests local recurrence following cCR may be a significant and independent risk factor for distant metastasis and that leaving the undetectable primary tumor in situ until recurrence occurs may result in poorer oncological outcomes.44,45 Despite salvage surgery being successful in almost all cases of local regrowth, more extensive surgeries may be required to achieve adequate local control. All DSAs suggested patient utilities for W&W and post-surgery may have changed the model outcome, highlighting the need for high-quality studies to refine these key parameters. Despite these limitations, PSA consistently supported W&W as the dominant strategy with high certainty.

Quality assessment tools in EE have several inherent pitfalls. No standardized tool exists, leading to the development of multiple checklists.29 The BMJ and Philips checklists were chosen as they were the most commonly used for trial- and model-based EEs, respectively;29 however, the subjective nature of these checklists results in high interrater variability, limiting the ability to provide reliable and consistent results.29 In this review, two independent reviewers performed each element of quality assessment, and disagreements were resolved either by consensus or a third reviewer, which helped reduce bias and systematic errors.30 Because no validated scoring systems of these checklists exist, it is important to emphasize that scores do not imply quality.26,27,28,29 Therefore, grading systems or arbitrary percentage cut-offs were not employed; instead, ESM 2 presents the complete matrix of quality assessment.

The results of this systematic review on the economic impact of W&W following neoadjuvant therapy for LARC suggest that W&W is likely cost effective and cost saving compared with surgery; however, caution is warranted given the small number of studies, clinical heterogeneity, and variable methodological quality of the included studies. Given these considerations, shared patient/clinician decision making is imperative. Nevertheless, our findings may aid the development of new decision-making models and in healthcare resource planning. Future research on patient-relevant health outcomes and societal cost effectiveness of W&W, particularly in the setting of TNT, are needed to further inform patients, clinicians, and policy makers.

Data availability

All template data collection forms, data extracted from included studies, data used for analysis, and other material used in the review may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Langenfeld SJ, Davis BR, Vogel JD, et al. The American society of colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of rectal cancer 2023 supplement. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024;67(1):18–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000003057.

Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Wynn G, Marks J, Kessler H, Gama-Rodrigues J. Complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer: characterization of clinical and endoscopic findings for standardization. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(12):1692–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f42b89.

Chen TY-T, Wiltink LM, Nout RA, et al. Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short-course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2015;14(2):106–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2014.12.007.

Paun BC, Cassie S, MacLean AR, Dixon E, Buie WD. Postoperative complications following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2010;251(5):807–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dae4ed.

Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):711–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000141194.27992.32.

van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, et al. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. The Lancet. 2018;391(10139):2537–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31078-X.

Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(35):4633–40. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.37.7176.

Renehan AG, Malcomson L, Emsley R, et al. Watch-and-wait approach versus surgical resection after chemoradiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer (the OnCoRe project): a propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):174–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00467-2.

Sammour T, Price BA, Krause KJ, Chang GJ. Nonoperative management or ‘watch and wait’ for rectal cancer with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: a critical appraisal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(7):1904–15. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5841-3.

Dossa F, Chesney TR, Acuna SA, Baxter NN. A watch-and-wait approach for locally advanced rectal cancer after a clinical complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(7):501–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30074-2.

Custers PA, Van Der Sande ME, Grotenhuis BA, et al. Long-term quality of life and functional outcome of patients with rectal cancer following a Watch-and-Wait approach. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(5):e230146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0146.

Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after chemoradiation: Watch-and-Wait policy versus standard resection – a matched-controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1032–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000000862.

Bedrikovetski S, Traeger L, Seow W, et al. Oncological outcomes and response rate after total neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a network meta-analysis comparing induction vs consolidation chemotherapy vs standard chemoradiation. Clin Colorectal Cancer. Epub 11 Jun 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2024.06.001

Conroy T, Bosset J-F, Etienne P-L, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):702–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00079-6.

Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, Van Etten B, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):29–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30555-6.

Liu J, Ladbury C, Glaser S, et al. Patterns of care for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with total neoadjuvant therapy at predominately academic centers between 2016–2020: an NCDB analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2023;22(2):167–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2023.01.005.

Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, et al. Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):465–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7826.

Grass F, Merchea A, Mathis KL, et al. Cost drivers of locally advanced rectal cancer treatment—An analysis of a leading healthcare insurer. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123(4):1023–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26390.

Childers CP, Maggard-Gibbons M. Understanding costs of care in the operating room. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):e176233. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6233.

Rao C, Sun Myint A, Athanasiou T, et al. Avoiding radical surgery in elderly patients with rectal cancer is cost-effective. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(1):30–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000708.

Miller JA, Wang H, Chang DT, Pollom EL. Cost-effectiveness and quality-adjusted survival of Watch and Wait after complete response to chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(8):792–801. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa003.

Cui CL, Luo WY, Cosman BC, et al. Cost effectiveness of watch and wait versus resection in rectal cancer patients with complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(3):1894–907. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10576-z.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890.

Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275.

Philips Z, Bojke L, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Golder S. Good practice guidelines for decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. PharmacoEconomics. 2006;24(4):355–71. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200624040-00006.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02204-0.

Watts RD, Li IW. Use of checklists in reviews of health economic evaluations, 2010 to 2018. Value Health. 2019;22(3):377–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.10.006.

Mandrik O, Severens JL, Bardach A, et al. Critical appraisal of systematic reviews with costs and cost-effectiveness outcomes: an ISPOR good practices task force report. Value Health. 2021;24(4):463–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.01.002.

Shemilt I, James T, Marcello M. A web-based tool for adjusting costs to a specific target currency and price year. Evid Policy. 2010;6(1):51–9. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410x482999.

Hendriks P. Health economic evaluation of watch and wait policy after clinical complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients [thesis]. Enschede: University of Twenty; 2016.

Hupkens BJP, Breukink SO, Stoot J, et al. Oncological outcomes and hospital costs of the treatment in patients with rectal cancer: Watch-and-Wait policy and standard surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(5):598–605. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001594.

Rodriguez-Pascual J, Nuñez-Alfonsel J, Ielpo B, et al. Watch-and-Wait policy versus robotic surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer: a cost-effectiveness study (RECCOSTE). Surg Oncol. 2022;41:101710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101710.

Ferri V, Vicente E, Quijano Y, et al. Light and shadow of watch-and-wait strategy in rectal cancer: oncological result, clinical outcomes, and cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38(1):277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-023-04573-9.

Gani C, Grosse U, Clasen S, et al. Cost analysis of a wait-and-see strategy after radiochemotherapy in distal rectal cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2018;194(11):985–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-018-1327-x.

Wurschi GW, Rühle A, Domschikowski J, et al. Patient-relevant costs for organ preservation versus radical resection in locally advanced rectal cancer. Cancers. 2024;16(7):1281.

Cooper EA, Hodder RJ, Finlayson A, et al. Cost analysis of a watch-and-wait approach in patients with a complete clinical response to chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92(11):2956–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.17914.

Crean R, Glyn T, McCombie A, Frizelle F. Comparing outcomes and cost in surgery versus watch & wait surveillance of patients with rectal cancer post neoadjuvant long course chemoradiotherapy. ANZ J Surg. 2024;94(6):1151–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.18916.

Sawada N, Mukai S, Takehara Y, et al. The “Watch and Wait” method after chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer requiring abdominoperineal resection. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2023;14(4):765–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-023-01831-8.

Loria A, Ramsdale EE, Aquina CT, Cupertino P, Mohile SG, Fleming FJ. From clinical trials to practice: anticipating and overcoming challenges in implementing watch-and-wait for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(8):876–80. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.23.01369.

Chin R-I, Otegbeye EE, Kang KH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total neoadjuvant therapy with short-course radiotherapy for resectable locally advanced rectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146312. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46312.

Wright ME, Beaty JS, Thorson AG, Rojas R, Ternent CA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of total neoadjuvant therapy followed by radical resection versus conventional therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(5):568–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001325.

Fernandez LM, São Julião GP, Renehan AG, et al. The risk of distant metastases in patients with clinical complete response managed by watch and wait after neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: the influence of local regrowth in the international watch and wait database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66(1):41–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000002494.

Fernandez LM, Julião GPS, Vailati BB, et al. Organ-preservation in rectal cancer: What is at risk when offering watch and wait for a clinical complete response? Data from 2 international registries in rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(3 Suppl):7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2024.42.3_suppl.7.

Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, et al. Assessment of a watch-and-wait strategy for rectal cancer in patients with a complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(4):e185896. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5896.

Marijnen CA, Kapiteijn E, Van de Velde CJ, et al. acute side effects and complications after short-term preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision in primary rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncolgy. 2002;20(3):817–25. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2002.20.3.817.

Ikoma N, You YN, Bednarski BK, et al. Impact of recurrence and salvage surgery on survival after multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2631–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.72.1464.

Couwenberg AM, Intven MPW, Burbach JPM, Emaus MJ, van Grevenstein WMU, Verkooijen HM. Utility scores and preferences for surgical and organ-sparing approaches for treatment of intermediate and high-risk rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(8):911–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001029.

van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Cost-utility analysis of preoperative radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer undergoing total mesorectal excision: a study of the dutch colorectal cancer group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):244–53. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.04.198.

Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2019; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Quality Payment Program; Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Program; Quality Payment Program-Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstance Policy for the 2019 MIPS Payment Year; Provisions from the Medicare Shared Savings Program-Accountable Care Organizations-Pathways to Success; and Expanding the Use of Telehealth Services for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder Under the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act (2018).

Raldow AC, Chen AB, Russell M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of short-course radiation therapy versus long-course chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2249.

DMEPOS Fee schedule (2020).

Duncan I, Ahmed T, Dove H, Maxwell TL. Medicare cost at end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Med®. 2019;36(8):705–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119836204.

Martens MH, Maas M, Heijnen LA, et al. Long-term outcome of an organ preservation program after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(12):djw171. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw171.

Appelt AL, Pløen J, Harling H, et al. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):919–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00120-5.

Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(9):835–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8.

Gebührenordnung für Ärzte (GOÄ) (2008).

Maas M, Lambregts DMJ, Nelemans PJ, et al. Assessment of clinical complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer with digital rectal examination, endoscopy, and MRI: selection for organ-saving treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3873–80. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4687-9.

Beets GL, Figueiredo NL, Habr-Gama A, van de Velde CJH. A new paradigm for rectal cancer: organ preservation: Introducing the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(12):1562–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2015.09.008.

Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, São Julião GP, et al. Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(4):822–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.012.

Nielsen MB, Laurberg S, Holm T. Current management of locally recurrent rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(7):732–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02167.x.

Ness RM, Holmes AM, Klein R, Dittus R. Utility valuations for outcome states of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(6):1650–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01157.x.

Li Y, Wang J, Ma X, et al. A review of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12(8):1022–31. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.15438.

Valentini V, Morganti AG, Gambacorta MA, et al. Preoperative hyperfractionated chemoradiation for locally recurrent rectal cancer in patients previously irradiated to the pelvis: a multicentric phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(4):1129–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.017.

Guren MG, Undseth C, Rekstad BL, et al. Reirradiation of locally recurrent rectal cancer: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113(2):151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2014.11.021.

Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Phelan M, Smith BR, Stamos MJ. Outcomes of open, laparoscopic, and robotic abdominoperineal resections in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(12):1123–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000000475.

Mohiuddin M, Marks G, Marks J. Long-term results of reirradiation for patients with recurrent rectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(5):1144–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10799.

World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory 2017 Update. 2017. Availbale at: https://www.who.int/gho/en/

Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.09.046.

Berger A, Inglese G, Skountrianos G, Karlsmark T, Oguz M. Cost-effectiveness of a ceramide-infused skin barrier versus a standard barrier: findings from a long-term cost-effectiveness analysis. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2018;45(2):146–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000416.

Smith FM, Rao C, Perez RO, et al. Avoiding radical surgery improves early survival in elderly patients with rectal cancer, demonstrating complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy: results of a decision-analytic model. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(2):159–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000000281.

Smith FM, Waldron D, Winter DC. Rectum-conserving surgery in the era of chemoradiotherapy. Br J Surg. 2010;97(12):1752–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7251.

Neuman HB, Elkin EB, Guillem JG, et al. Treatment for patients with rectal cancer and a clinical complete response to neoadjuvant therapy: a decision analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(5):863–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819eefba.

Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. BJS (Br J Surg). 2012;99(7):918–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8702.

Valentini V, Van Stiphout RG, Lammering G, et al. Nomograms for predicting local recurrence, distant metastases, and overall survival for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer on the basis of European randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncolgy. 2011;29(23):3163–72. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.33.1595.

Guillem JG, Chessin DB, Cohen AM, et al. Long-term oncologic outcome following preoperative combined modality therapy and total mesorectal excision of locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):829–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000161980.46459.96.

García-Aguilar J, Hernandez de Anda E, Sirivongs P, Lee S-H, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA. A pathologic complete response to preoperative chemoradiation is associated with lower local recurrence and improved survival in rectal cancer patients treated by mesorectal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(3):298–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-6545-x.

Tepper JE, O’Connell M, Hollis D, Niedzwiecki D, Cooke E, Mayer RJ. Analysis of surgical salvage after failure of primary therapy in rectal cancer: results from intergroup study 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3623–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2003.03.018.

Mvd Brink, Stiggelbout AM, Hout WBvd, et al. Clinical nature and prognosis of locally recurrent rectal cancer after total mesorectal excision with or without preoperative radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(19):3958–64. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.01.023.

National Life Tables: United Kingdom (2013).

Hahnloser D, Nelson H, Gunderson LL, et al. Curative potential of multimodality therapy for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2003;237(4):502–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Sla.0000059972.90598.5f.

Cassidy J, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, et al. Randomized phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):2006–12. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.14.9898.

Konski A, Watkins-Bruner D, Feigenberg S, et al. Using decision analysis to determine the cost-effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the treatment of intermediate risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(2):408–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.049.

Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2013–2014. 2014.

Quijano Y, Nuñez-Alfonsel J, Ielpo B, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a comparative cost-effectiveness study. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(3):247–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02151-7.

Garcia-Aguilar J, Patil S, Gollub MJ, et al. Organ preservation in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma treated with total neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(23):2546–56. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.22.00032.

Verheij FS, Omer DM, Williams H, et al. Long-term results of organ preservation in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma treated with total neoadjuvant therapy: the randomized phase II OPRA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(5):500–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.23.01208.

Rödel C, Graeven U, Fietkau R, et al. Oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy of locally advanced rectal cancer (the German CAO/ARO/AIO-04 study): final results of the multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):979–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00159-X.

Diefenhardt M, Martin D, Fleischmann M, et al. Overall survival after treatment failure among patients with rectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2340256. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.40256.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Federal Statistical Office). Deutsches Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS). Accessed 8 Jan 2024. Available at: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online.

Kosmala R, Fokas E, Flentje M, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients with or without oxaliplatin in the randomised CAO/ARO/AIO-04 phase 3 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:281–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.029.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank David John Tamblyn and Camille Schubert from the Adelaide Health Technology Assessment Unit for their assistance and review.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No external funding was received for this project. Ishraq Murshed is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and The University of Adelaide.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

Ishraq Murshed, Zachary Bunjo, Warren Seow, Ishmam Murshed, Sergei Bedrikovetski, Michelle Thomas, and Tarik Sammour have declared no conflicts of interest that may be relevant to the contents of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murshed, I., Bunjo, Z., Seow, W. et al. Economic Evaluation of ‘Watch and Wait’ Following Neoadjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Ann Surg Oncol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-16056-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-16056-4