Abstract

Background

A relationship between hospital procedural volume and patient outcomes has been observed in gastrectomies for primary gastric cancer, but modifiable factors influencing this relationship are not well elaborated.

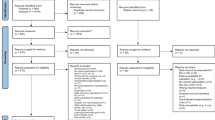

Methods

We performed a population-based study of 1864 patients undergoing gastrectomy for primary gastric cancers at 214 hospitals. Hospitals were stratified as high-, intermediate-, or low-volume centers. Multivariate models were constructed to evaluate the effect of institutional procedural volume and other hospital- and patient-specific factors on the risk of in-hospital mortality, adverse events, and failure to rescue, defined as mortality after an adverse event.

Results

High-volume centers attained an in-hospital mortality rate of 1.0% and failure-to-rescue rate of .7%, both less than one-fifth of that seen at intermediate- and low-volume centers, although adverse event rates were similar across the three volume tiers. In multivariate modeling, treatment at a high-volume hospital decreased the odds of mortality (odds ratio [OR], .22; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], .05–.89), whereas treatment at an institution with a high ratio of licensed vocational nurses per bed increased the odds of mortality (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.04–3.75). Being treated at a hospital with a greater than median number of critical care beds decreased odds of mortality (OR, .46; 95% CI, .25–.81) and failure to rescue (OR, .53; 95% CI, .29–.97).

Conclusions

Undergoing gastrectomy at a high-volume center is associated with lower in-hospital mortality. However, improving the rates of mortality after adverse events and reevaluating nurse staffing ratios may provide avenues by which lower-volume centers can improve mortality rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reference

Macintyre IM, Akoh JA. Improving survival in gastric cancer: review of operative mortality in English language publications from 1970. Br J Surg 1991;78:771–6

Msika S, Benhamiche AM, Tazi MA, Rat P, Faivre J. Improvement of operative mortality after curative resection for gastric cancer: population-based study. World J Surg 2000;24:1137–42

Wainess RM, Dimick JB, Upchurch GR Jr, Cowan JA, Mulholland MW. Epidemiology of surgically treated gastric cancer in the United States, 1988–2000. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:879–83

Damhuis RA, Meurs CJ, Dijkhuis CM, Stassen LP, Wiggers T. Hospital volume and post-operative mortality after resection for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:401–5

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128–37

Hannan EL, Radzyner M, Rubin D, Dougherty J, Brennan MF. The influence of hospital and surgeon volume on in-hospital mortality for colectomy, gastrectomy, and lung lobectomy in patients with cancer. Surgery 2002;131:6–15

Bachmann MO, Alderson D, Edwards D, et al. Cohort study in South and West England of the influence of specialization on the management and outcome of patients with oesophageal and gastric cancers. Br J Surg 2002;89:914–22

Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg 2003;138:721–5

Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1364–9

Hughes RG, Hunt SS, Luft HS. Effects of surgeon volume and hospital volume on quality of care in hospitals. Med Care 1987;25:489–503

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA 1998;280:1747–51

Flood AB, Scott WR, Ewy W. Does practice make perfect? Part I: The relation between hospital volume and outcomes for selected diagnostic categories. Med Care 1984;22:98–114

Flood AB, Scott WR, Ewy W. Does practice make perfect? Part II: The relation between volume and outcomes and other hospital characteristics. Med Care 1984;22:115–25

Daly JM. Society of Surgical Oncology presidential address: volume, outcome, and surgical specialization. Ann Surg Oncol 2004;11:107–14

Birkmeyer JD. Should we regionalize major surgery? Potential benefits and policy considerations. J Am Coll Surg 2000;190:341–9

Dudley RA, Johansen KL, Brand R, Rennie DJ, Milstein A. Selective referral to high-volume hospitals: estimating potentially avoidable deaths. JAMA 2000;283:1159–66

Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care 1992;30:615–29

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83

Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075–9

Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care 1994;32:700–15

Rosen AK, Geraci JM, Ash AS, McNiff KJ, Moskowitz MA. Postoperative adverse events of common surgical procedures in the Medicare population. Med Care 1992;30:753–65

McCarthy EP, Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, et al. Does clinical evidence support ICD-9-CM diagnosis coding of complications? Med Care 2000;38:868–76

Lawthers AG, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Peterson LE, Palmer RH, Iezzoni LI. Identification of in-hospital complications from claims data. Is it valid? Med Care 2000;38:785–95

Romano PS, Chan BK, Schembri ME, Rainwater JA. Can administrative data be used to compare postoperative complication rates across hospitals? Med Care 2002;40:856–67

Hannan EL, O’Donnell JF, Kilburn H Jr, Bernard HR, Yazici A. Investigation of the relationship between volume and mortality for surgical procedures performed in New York State hospitals. JAMA 1989;262:503–10

Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2327–40

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002;288:1987–93

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA 2003;290:1617–23

Norris S, Morgan R. Providers issue brief: nursing shortages: year end report—2002. Issue Brief Health Policy Track Serv 2002:1–14

Jencks SF, Williams DK, Kay TL. Assessing hospital-associated deaths from discharge data. The role of length of stay and comorbidities. JAMA 1988;260:2240–6

Karp HR, Flanders WD, Shipp CC, Taylor B, Martin D. Carotid endarterectomy among Medicare beneficiaries: a statewide evaluation of appropriateness and outcome. Stroke 1998;29:46–52

Cebul RD, Snow RJ, Pine R, Hertzer NR, Norris DG. Indications, outcomes, and provider volumes for carotid endarterectomy. JAMA 1998;279:1282–7

Houghton A. Variation in outcome of surgical procedures. Br J Surg 1994;81:653–60

Birkmeyer JD, Lucas FL, Wennberg DE. Potential benefits of regionalizing major surgery in Medicare patients. Eff Clin Pract 1999;2:277–83

Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, Nease RF Jr. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care 1999;37:204–9

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by William Randolph Hearst Foundations and the Carlos Cantu Foundation Fund for Research in Surgical Oncology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, D.L., Elting, L.S., Learn, P.A. et al. Factors Influencing the Volume-Outcome Relationship in Gastrectomies: A Population-Based Study. Ann Surg Oncol 14, 1846–1852 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9381-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9381-0