Abstract

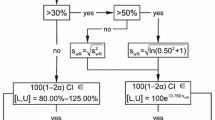

In order to help companies qualify and validate the software used to evaluate bioequivalence trials in a replicate design intended for average bioequivalence with expanding limits, this work aims to define datasets with known results. This paper releases 30 reference datasets into the public domain along with proposed consensus results. A proposal is made for results that should be used as validation targets. The datasets were evaluated by seven different software packages according to methods proposed by the European Medicines Agency. For the estimation of CVwR and Method A, all software packages produced results that are in agreement across all datasets. Due to different approximations of the degrees of freedom, slight differences were observed in two software packages for Method B in highly incomplete datasets. All software packages were suitable for the estimation of CVwR and Method A. For Method B, different methods for approximating the denominator degrees of freedom could lead to slight differences, which eventually could lead to contrary decisions in very rare borderline cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence. London. 2010. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-investigation-bioequivalence-rev1_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the pharmacokinetic and clinical evaluation of modified release dosage forms. London. 2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-pharmacokinetic-clinical-evaluation-modified-release-dosage-forms_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

World Health Organization, Essential Medicines and Health Products: Multisource (generic) pharmaceutical products: guidelines on registration requirements to establish interchangeability. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1003, Annex 6. Geneva. 2017. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23245en/s23245en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

World Health Organization, Prequalification Team: medicines. Guidance Document: application of reference-scaled criteria for AUC in bioequivalence studies conducted for submission to PQTm. Geneva. 2018. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/documents/AUC_criteria_November2018.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Australian Government, Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. European Union and ICH Guidelines adopted in Australia. Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence with TGA Annotations. https://www.tga.gov.au/ws-sg-index?search_api_views_fulltext=bioequivalence&field_ws_sg_category1=9140. Accessed 15 November 2019.

East African Community, Medicines and Food Safety Unit. Compendium of Medicines Evaluation and Registration for Medicine Regulation Harmonization in the East African Community, Part III: EAC Guidelines on Therapeutic Equivalence Requirements. 2014. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22312en/s22312en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

ASEAN States Pharmaceutical Product Working Group. ASEAN guideline for the conduct of bioequivalence studies. Vientiane. 2015. https://www.npra.gov.my/images/reg-info/BE/BE_Guideline_FinalMarch2015_endorsed_22PPWG.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Eurasian Economic Commission. Regulations Conducting Bioequivalence Studies within the Framework of the Eurasian Economic Union. 2016. https://docs.eaeunion.org/docs/ru-ru/01411942/cncd_21112016_85. Accessed 15 November 2019. Russian.

Ministry of Health and Population, The Specialized Scientific Committee for Evaluation of Bioavailability & Bioequivalence Studies. Egyptian Guideline For Conducting Bioequivalence Studies for Marketing Authorization of Generic Products. Cairo. 2017. http://www.eda.mohp.gov.eg/Files/1092_Egyptian_Guideline_Conducting_Bioequivalence_Studies.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Guideline on the Regulation of Therapeutic Products in New Zealand. Part 6: Bioequivalence of medicines. Wellington. 2018. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/regulatory/Guideline/GRTPNZ/bioequivalence-of-medicines.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Tóthfalusi L, Endrényi L, García AA. Evaluation of bioequivalence for highly variable drugs with scaled average bioequivalence. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48(11):725–43. https://doi.org/10.2165/11318040-000000000-00000.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, CDRH, CBER. General Principles of Software Validation; Final Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. Rockville. 2002. https://www.fda.gov/media/73141/download. Accessed 15 November 2019.

European Medicines Agency. GCP Inspectors Working Group. Reflection paper on expectations for electronic source data and data transcribed to electronic data collection tools in clinical trials. London. 2010. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/reflection-paper-expectations-electronic-source-data-data-transcribed-electronic-data-collection_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

International Council for Harmonisation. Integrated addendum to ICH E6(R1): Guideline for good clinical practice E6(R2). 2016. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

World Health Organization. Technical Report Series No. 996, Annex 9. Guidance for organizations performing in vivo bioequivalence studies (revision). Geneva. 2016. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/pharmprep/WHO_TRS_996_annex09.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Schütz H, Labes D, Fuglsang A. Reference datasets for 2-treatment, 2-sequence, 2-period bioequivalence studies. AAPS J. 2014;16(6):1292–7. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-014-9661-0.

Fuglsang A, Schütz H, Labes D. Reference datasets for bioequivalence trials in a two-group parallel design. AAPS J. 2015;17(2):400–4. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-014-9704-6.

European Medicines Agency. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics: questions and answers. 3.1 Which statistical method for the analysis of a bioequivalence study does the Agency recommend? Annex II. London. 2011. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/31-annex-ii-statistical-analysis-bioequivalence-study-example-data-set_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Patterson SD, Jones B. Bioequivalence and statistics in clinical pharmacology. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. p. 105–6.

Shumaker RC, Metzler CM. The phenytoin trial is a case study of ‘individual’ bioequivalence. Drug Inf J. 1998;32(4):1063–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/009286159803200426.

Hauschke D, Steinijans VW, Pigeot I. Bioequivalence studies in drug development. Chichester: John Wiley; 2007. p. p216.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, CDER. Bioequivalence Studies. Bioequivalence study files. Rockville. 1997. https://web.archive.org/web/20170723175533/https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ScienceResearch/UCM301481.zip. Archived 23 July 2017. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Chow SC, Liu JP. Design and analysis of bioavailability and bioequivalence studies. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2009. p. 275.

Balaam LN. A two-period design with t2 experimental units. Biometrics. 1968;24(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2528460.

European Medicines Agency. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics: questions and answers. 3.1 Which statistical method for the analysis of a bioequivalence study does the Agency recommend? Annex III. London. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/statistical-method-equivalence-studies-annex-iii_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Patterson SD, Jones B. Viewpoint: observations on scaled average bioequivalence. Pharm Stat. 2012;11(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.498.

Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H. Individual bioequivalence testing under 2×3 designs. Stat Med. 2002;21(5):629–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1056.

European Medicines Agency. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics: questions and answers. 3.1 Which statistical method for the analysis of a bioequivalence study does the Agency recommend? Annex I. London. 2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/31-annex-i-statistical-analysis-methods-compatible-ema-bioequivalence-guideline_en.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Schütz H, Tomashevskiy M, Labes D. replicateBE: Average Bioequivalence with Expanding Limits (ABEL). 2020; R package version 1.0.13. https://cran.r-project.org/package=replicateBE.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. 2019. https://www.r-project.org/.

SAS Institute. SAS® 9.4 and SAS® Viya® 3.4 Programming Documentation / SAS/STAT User’s Guide. The MIXED Procedure. 2019. https://go.documentation.sas.com/?cdcId=pgmsascdc&cdcVersion=9.4_3.4&docsetId=statug&docsetTarget=statug_mixed_syntax10.htm#statug.mixed.modelstmt_ddfm. Accessed 15 November 2019.

West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear mixed models: a practical guide using statistical software. 2nd ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2014. p. 131.

Satterthwaite FE. An approximate distribution of estimates of variance components. Biom Bull. 1946;2(6):110–4. https://doi.org/10.2307/3002019.

Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53(3):983–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533558.

Certara University. (106-FL) Free phoenix templates for bioequivalence regulatory guidances. 2017. https://www.certarauniversity.com/learn/course/external/view/elearning/318/106-FLFreePhoenixTemplatesforBioequivalenceRegulatoryGuidances. Accessed 23 August 2019.

US Food and Drug Administration, CDER. Guidance for Industry. Statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence. Rockville. 2001. https://www.fda.gov/media/70958/download. Accessed 15 November 2019.

SAS Institute. JMP 14.2 online documentation. The Kackar-Harville Correction https://www.jmp.com/support/help/14-2/the-kackar-harville-correction-2.shtml. Accessed 10 January 2020.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mahmoud Teaima (Cairo University, Faculty of Pharmacy) for testing an earlier version of the R package replicateBE and four reviewers whose comments substantially improved this article.

Contributors

The concept was developed by HS, DL, MT, and AS. HS (replicateBE, Phoenix), DL, MT (SAS), MG (Stata, SPSS, JMP), and AS (STATISTICA) were responsible for analyses with the respective software packages. HS drafted the manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

HS received a “named license” of Phoenix from Certara. DL, MT, MG, AS, and AF have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schütz, H., Labes, D., Tomashevskiy, M. et al. Reference Datasets for Studies in a Replicate Design Intended for Average Bioequivalence with Expanding Limits. AAPS J 22, 44 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-020-0427-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-020-0427-6