Abstract

The global brachiopod palaeobiogeography of the Mississippian is divided into three realms, six regions, and eight provinces, while that of the Pennsylvanian is divided into three realms, six regions, and nine provinces. On this basis, we examined coevolutionary relationships between brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography using a comparative approach spanning the Carboniferous. The appearance of the Boreal Realm in the Mississippian was closely related to movements of the northern plates into middle–high latitudes. From the Mississippian to the Pennsylvanian, the palaeobiogeography of Australia transitioned from the Tethys Realm to the Gondwana Realm, which is related to the southward movement of eastern Gondwana from middle to high southern latitudes. The transition of the Yukon–Pechora area from the Tethys Realm to the Boreal Realm was associated with the northward movement of Laurussia, whose northern margin entered middle–high northern latitudes then. The formation of the six palaeobiogeographic regions of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian brachiopods was directly related to “continental barriers”, which resulted in the geographical isolation of each region. The barriers resulted from the configurations of Siberia, Gondwana, and Laurussia, which supported the Boreal, Tethys, and Gondwana realms, respectively. During the late Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, the Rheic seaway closed and North America (from Laurussia) joined with South America and Africa (from Gondwana), such that the function of “continental barriers” was strengthened and the differentiation of eastern and western regions of the Tethys Realm became more distinct. In the Barents Ocean tectonic domain during the Pennsylvanian, the brachiopods on the northern margin of the Barents Ocean formed the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province, while those on the southern margin formed the Yukon–Pechora Province. The Mongolia–Okhotsk Province was formed by brachiopods of the Mongolia–Okhotsk Ocean tectonic domain. The Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province and the Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province were formed, respectively, by brachiopods on the northern and southern margins of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean tectonic domain. South China and Southeast Asia were dissociated from the major continental blocks mentioned above, and formed the South China Province.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The formation and evolution of Pangaea during the Carboniferous and Permian was one of the major tectonopalaeogeographic events in the history of the Earth. The palaeobiogeographic realms, regions, and numerous provinces of brachiopod palaeobiogeography during this time have been clearly demarcated. The relationship between palaeobiogeographic and tectonic patterns has been a geobiological question of great importance (Bottjer 2005; Lieberman 2005; Noffke 2005). The present study examines the coevolution of palaeobiogeographic and tectonopalaeogeographic patterns based on a comparative analysis of the biogeography of Carboniferous brachiopod faunas and the formation and evolution of Pangaea. Thus, palaeobiogeographic provincialism and the early formation and evolution of Pangaea through the Carboniferous are the focus of this study.

Preliminary studies of Carboniferous brachiopod palaeobiogeography include those of Ivanova et al. (1979), Yang (1988, 1990), Wang (1994), Qiao and Shen (2014), and Wang et al. (2014). However, these studies are inadequate for the comparative analysis of the scope intended in the present study. In this study on global brachiopod palaeobiogeography, we selected characteristic genera representing palaeobiogeographic units at different levels (realm, region, and province) and, based on a comprehensive analysis of known genera from each epoch of the Carboniferous, we reconstructed the palaeobiogeographic provincialism. During the Carboniferous, many genera exhibiting bipolar distributions were also representative of particular provinces; these genera have been given particular attention in this study.

Numerous studies have examined the formation and evolution of Pangaea (Scotese and McKerrow 1990; Golonka and Ford 2000; Vai 2003; Bozkurt et al. 2008; Nance 2010; Boucot et al. 2013; Jastrzębski et al. 2013), which involved closure of the Rheic seaway during the Famennian (Late Devonian)–Early Mississippian, the collision of Gondwana and Laurussia, and the formation of the Variscan Orogenic Belt. However, these studies on the coevolution of palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography have been generally restricted to either a particular period (Qiao and Shen 2014) or region (Wang et al. 2013, 2014). Thus, there is currently a lack of comprehensive and in-depth research on this topic.

This study on the coevolution of palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography will contribute to our understanding of the formation mechanisms of palaeobiogeographic patterns, which are the basis for palaeobiogeographic provincialism; and the results will also improve our understanding of existing tectonopalaeogeographic modes.

2 Palaeobiogeographic provincialism of brachiopods during the Carboniferous

2.1 Palaeobiogeographic provincialism of brachiopods during the Mississippian

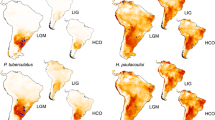

Based on the geographic distribution of 325 brachiopod genera from 42 regions globally (Fig. 1, see Supplementary Table) with preserved Mississippian brachiopods, the Mississippian brachiopod palaeobiogeography has been divided into three realms, six regions, and eight provinces (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Distribution of Mississippian brachiopod fauna. Fossil locations and material sources are as follows: 1. Chita (Kotlyar 2002); 2. Uliastaj (Yang 1990); 3. north Junggar (Zhang et al. 1983); 4. Rudny Altay (Gretchishnikova 1966); 5. Kuznetsk Basin (Sarytcheva et al. 1963); 6. Verkhoyansk (Abramov and Grigoryeva 1983, 1986); 7. Yukon (Bamber and Waterhouse 1971); 8. Alaska (Rodriguez and Gutschick 1968, 1969); 9. western Alberta (McGugan and May 1965; Carter 1987, 1988); 10. California (Watkins 1974); 11. central United States (Weller 1905, 1914; Carter 1968, 1972); 12. southwestern United States (Carter 1967); 13. Mexico (Navarro-Santillán et al. 2002; Sour-Tovar et al. 2005; Torres-Martínez et al. 2018); 14. Madama (Mergl et al. 2001); 15. France (Paeckelmann 1931); 16. England (Brunton 1966, 1968; Bassett and Bryant 2006); 17. near Moscow (Sarytcheva and Solkolskaya 1952); 18. southern Ural Mountains (Nalivkin 1979); 19. Azerbaijan (Grechishnikova and Levitskii 2011); 20. Astana (Litvinovich 1962); 21. Kyrgyzstan (Galitzkaja 1977); 22. Borohoro Mountains (Yang 1964a); 23. Gancaohu (Zhang et al. 1983; Chen and Archbold 2000); 24. Hami (Zhang et al. 1983); 25. Beishan (Ding 1985); 26. central Jilin (Liu 1988); 27. Mishan (Su and Gu 1987); 28. Hubei Province (Wang 1984); 29. Hunan Province (Liu et al. 1982); 30. Yunnan–Guizhou (Yang 1964b; Yang 1978); 31. Hainan Province (Liao and Zhang 2006); 32. Malaya (Muir-Wood 1948); 33. Bonaparte Gulf Basin (Roberts 1971; Thomas 1971); 34. Canning Basin (Thomas 1971); 35. Queensland (Maxwell 1960, 1961); 36. New South Wales (Campbell 1956, 1957; Cvancara 1958; Campbell and Roberts 1964; Roberts 1964); 37. Carnarvon Basin (Thomas 1971); 38. Mount Jolmo Lungma region (Zhang and Jin 1976; Yang and Fan 1983); 39. Nepal (Waterhouse 1966); 40. western Karakoram (Gaetani et al. 2004); 41. northern Chile (Isaacson and Dutro 1999); 42. central and western Argentina (Taboada 2010)

2.1.1 Boreal Realm

During the Mississippian, the Boreal Palaeobiogeographic Realm (herein “Boreal Realm”) included the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province”) of the Barents Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “Barents Region”) and the Mongolia–Okhotsk Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Mongolia–Okhotsk Province”) of the Central Asia Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “Central Asia Region”) (Wang et al. 2013, 2014) (Fig. 2).

Characteristic genera of the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province included Andreaspira, Arktikina, Bailliena, Buxtoniella, Nordathyris, Ovlatchania, Paeckelmanella, Praehorridonia, Sajakella, Taimyrella, Tulathyris, Verchojania, and Ziganella, and one of these genera (Sajakella) showed a bipolar distribution (Table 2).

Characteristic genera of the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province included Iniathyris, Mucrospirifer, Rhynchotetra, Steinhagella, Tenticospirifer, Tomilia, Ulbospirifer, Whidbornella, Zaissania, and two genera (Absenticosta and Levipustula) with a bipolar distribution (Table 2).

The above characteristic genera of the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr and Mongolia–Okhotsk provinces, and the genera common to the two provinces, such as Lanipustula, Martiniopsis, Nekhoroshevia, and Orulgania, along with some genera that showed a bipolar distribution during this time, constituted the characteristic genera of the Boreal Realm.

The exact time of formation of the Boreal Realm remains controversial. One viewpoint is that the Boreal Realm formed in the Tournaisian (Early Mississippian) (Wang et al. 2013, 2014); the other viewpoint is that the global provincialism was not evident during the Tournaisian or the Visean, and that the Boreal Realm did not exist prior to the Serpukhovian (Qiao and Shen 2014). It is essential to make a further discussion.

A diverse fauna of Tournaisian–Visean brachiopods developed in the Verkhoyansk area (Abramov and Grigoryeva 1983, 1986), including many endemic genera, such as Andreaspira, Arktikina, Bailliena, Buxtoniella, Martiniopsis, Nekhoroshevia, Nordathyris, Ovlatchania, Paeckelmanella, Praehorridonia, Sajakella, Taimyrella, Tulathyris, and Ziganella. These genera were characteristic of the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province, but none were present in the Tethys Realm. Meanwhile, the characteristic genera of the Boreal Realm, Lanipustula and Orulgania, were also present in Verkhoyansk, showing the obvious characteristics of the Boreal Realm.

The Mississippian brachiopod fauna from Chita (Kotlyar 2002) was not very diverse, and many of the taxa were widespread. However, the Serpukhovian genera Absenticosta, Lanipustula and Zaissania show characteristics of the Boreal Realm. Orulgania, which appeared in the Visean, is also represented in the Boreal Realm (Table 2).

The Tournaisian genera Ulbospirifer and Whidbornella from Rudny Altay also show characteristics of the Boreal Realm.

Although the Tournaisian–Visean brachiopod fauna from the Kuznetsk Basin showed a high diversity, the genera Iniathyris, Rhynchotetra, Septosyringothyris, Steinhagella, Tenticospirifer, and Tomilia showed similarities to taxa of the Boreal Realm. In terms of palaeogeography, the Kuznetsk Basin was probably located in the transition zone between the Boreal and Tethys realms.

2.1.2 Tethys Realm

The Tethys Palaeobiogeographic Realm (herein “Tethys Realm”), located between the Boreal Realm and the Gondwana Palaeobiogeographic Realm (herein “Gondwana Realm”), was a broad palaeoequatorial region. The Tethys Realm can be divided into the North America Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “North America Province”) of the West Tethys Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “West Tethys Region”), and the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province”), the South China Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “South China Province”; Yang 1983), and the Australia Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Australia Province”) of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region”; also called the “East Tethys Region”).

The characteristic genera of the North America Province included Acambona, Acanthospira, Alispirifer, Allorhynchus, Axiodeaneia, Bispinoproductus, Caenanoplia, Calvustrigis, Camarophorella, Centronelloidea, Chonopectus, Cyphotalosia, Diaphragmus, Dielasmella, Gacina, Hamburgia, Karavankina, Lissomarginifera, Merista, Moorefieldella, Nucleospira, Paraphorhynchus, Paurogastroderhynchus, Perditocardinia, Petrocrania, Piloricilla, Planalvus, Planoproductus, Plectospira, Ptychospira, Retichonetes, Rowleyella, Saharonetes, Shumardella, Skelidorygma, Spiriferella, Strophalosia, Subglobosochonetes, and Syringospira.

It has been suggested in several works that there is a strong affinity among the Mississippian brachiopods of Mexico and coeval faunas from the central and southeastern United States (Navarro-Santillán et al. 2002; Sour-Tovar et al. 2005; Torres-Martínez et al. 2018), and this similarity increases with the age of the faunas (Torres-Martínez et al. 2018). Anthracospirifer and Flexaria from the Tournaisian–Visean (Early–Middle Mississippian) brachiopod fauna of Madama in northern Africa (Mergl et al. 2001) show a relationship with taxa in the North America Province. However, Antiquatonia also appeared in the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region. The attributes and characteristics that define the Madama brachiopod fauna require further research, as the diversity of brachiopods discovered to date is low. In this study, we tentatively place the brachiopod fauna of Madama in the North America Province.

The characteristic genera of the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province included Acanthocrania, Beleutella, Brochocarina, Davidsonina, Ferganoproductus, Grandispirifer, Isogramma, Kadraliproductus, Kisilia, Levitusia, Linoprotonia, Marginifera, Nigeroplica, Orbinaria, Parallelora, Reticulatia, Scutepustula, Serratocrista, Sinotectirostrum, Thomasella, and Zalvera. Gigantoproductus was also a common genus in the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province (Table 2).

The brachiopods from the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran (Qiao et al. 2017) have a strong affinity with the fauna of Azerbaijan, and were not far from Iran. Therefore, it will not be set up as a fossil location alone.

The South China Province of the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region was characterized by the following genera: Desquamatia, Echinaria, Eudoxina, Gondolina, Guizhouella, Hunanoproductus, Martiniella, Neochonetes, Praewaagenoconcha, Subspirifer, and Yanguania. Gigantoproductus was also a common genus in the South China Province (Table 2).

The characteristic genera of the Australia Province included Acanthocosta, Asyrinxia, Austrochoristites, Balanoconcha, Cardiothyris, Grammorhynchus, Lomatiphora, Pleuropugnoides, Proboscidella, Protoniella, Rossirhynchus, Schistochonetes, Spinauris, and Werriea. Unispirifer and Kitakamithyris were also common (Table 2).

The above characteristic genera of the three provinces of the Palaeo-Tethys Region, and the genera that are common to two or three of these three provinces, such as Daviesiella, Delepinea, Ericiatia, Globosochonetes, Kansuella, Megachonetes, Marginicinctus, Palaeochoristites, Phricodothyris, Productus, Pugilis, Semiplanus, Spinulicosta, and Unispirifer, constituted the characteristic genera of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region. The Palaeo-Tethys Region included up to 60 characteristic brachiopod genera.

The characteristic genera of the West Tethys Region and the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region, and the genera common to these two regions, comprised the characteristic genera of the Tethys Realm. The Tethys Realm included a total of 130 genera, including Acanthoplecta, Ambocoelia, Camarophoria, Coledium, Cranaena, Crassumbo, Cyrtina, Daviesiella, Delepinea, Dorsoscyphus, Heteralosia, Krotovia, Lamellosathyris, Magnumbonella, Martinia, Productina, Pugnax, Sinuatella, Spinocarinifera, Spiriferina, and Voiseyella.

2.1.3 Gondwana Realm

The Gondwana Palaeobiogeographic Realm (herein “Gondwana Realm”) is divided into the West Argentina Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “West Argentina Province”) of the West Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “West Gondwana Region”) and the Himalaya Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Himalaya Province”) of the East Gondwana Palaeobiogeographic Region (herein “East Gondwana Region”).

The West Argentina Province was characterized by the following genera: Aseptella, Azurduya, Bulahdelia, Chilenochonetes, Costuloplica, and Yagonia, as well as Absenticosta and Levipustula, which exhibited a bipolar distribution (Table 2). We note here that the brachiopod fauna described by Chen et al. (2005) from the Upper Mississippian Itaituba Formation in the Amazon Basin, Brazil, is more similar to Pennsylvanian than Mississippian faunas; hence, we do not include these brachiopods here.

The characteristic genera of the Himalaya Province included Adminiculoria, Afghanospirifer, Buxtonioides, Cubacula, Dowhatania, Gypospirifer, Marginoproductus, and Marginovatia, as well as some genera with a bipolar distribution, such as Martiniopsis and Sajakella (Table 2).

The characteristic genera of the Gondwana Realm were represented by the characteristic genera of both the East Gondwana and West Gondwana regions. Genera that exhibited a bipolar distribution were also important representatives of the Gondwana Realm.

2.2 Palaeobiogeographic provincialism of brachiopods during the Pennsylvanian

According to existing data, 257 Pennsylvanian brachiopod genera have been identified at 33 locations (Fig. 3; see Supplementary Table). These brachiopods can be divided into three palaeobiogeographic realms, six palaeobiogeographic regions, and nine palaeobiogeographic provinces (Table 3; Fig. 4).

Distribution of Pennsylvanian brachiopod faunas. Fossil locations and material sources are as follows: 1. Verkhoyansk (Abramov and Grigoryeva 1983); 2. Taymyr (Ustritsky and Chernyak 1963); 3. Timan–Pechora (Kalashnikov 1980); 4. Balkhash (Sarytcheva 1968); 5. Shiqiantan (Wang and Yang 1998); 6. Chita (Kotlyar 2002); 7. Yukon (Bamber and Waterhouse 1971); 8. central United States (Dunbar and Condra 1932; Hoare 1960; Hoare and Burgess 1960); 9. the Great Basin (Watkins 1974; Pérez-Huerta 2006); 10. southwestern United States (Lane 1963; Sutherland and Harlow 1967; Beus and Lane 1969; Brew and Beus 1976); 11. Columbia (Rocha Campos 1985); 12. Brazil (Chen et al. 2005); 13. Peru (Newell et al. 1953); 14. Spain (Winkler Prins 1971, 2007; Martínez Chacón and Winkler Prins 1977, 1979, 2005, 2015); 15. Algeria (Legrand-Blain 1985; Kora 1995; Atif and Legrand-Blain 2011); 16. Onega (Nelzina 1965); 17. near Moscow (Sarytcheva and Solkolskaya 1952); 18. Samarra (Prokofev 1975); 19. Bashkir (Mironova 1967); 20. Kunlun Mountains (Ustritsky 1960; Chen and Shi 2000); 21. Borohoro Mountains (Yang 1964a); 22. Qilian Mountains (Yang et al. 1962); 23. Benbatu, Inner Mongolia (Lee and Gu 1980); 24. Taiyuan City of Shanxi Province (Lee and Gu 1980; He et al. 1995); 25. Benxi City of Liaoning Province (Lee and Gu 1980; Liu 1987); 26. Yanbian County of Sichuan Province (Tong et al. 1990); 27. Markam (Jin and Sun 1981); 28. Wardak (Reed 1931); 29. Chitral (Reed 1925); 30. Shenzha–Yongzhu County (Yang and Fan 1982; Zhan et al. 2007); 31. Bowen–Yarrol Basin (Roberts et al. 1976; Waterhouse 1987); 32. Sydney Basin (Campbell 1961; Roberts et al. 1976); and 33. western Argentina (Rocha Campos 1985; Taboada 2010; Cisterna and Sterren 2016)

2.2.1 Boreal Realm

The Boreal Realm during the Pennsylvanian can be divided into the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province and Yukon–Pechora Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Yukon–Pechora Province”) of the Barents Region and the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province of the Central Asia Region (Fig. 4).

The Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province included many characteristic genera, such as Achunoproductus, Anidanthus, Domokhotia, Jakutella, Jakutochonetes, Lingulodiscina, Martinothyris, Plectospira, Rhynoleichus, Shumardella, Settedabania, Tetracamera, Tiramnia, Uraloproductus, and Verchojania, as well as some genera with a bipolar distribution, such as Alispirifer, Attenuatella, Lanipustula, Tomiopsis and Trigonotreta (Table 4).

The characteristic genera of the Yukon–Pechora Province included Cranaena, Meristorygma, Onopordumaria, Horridonia, Rostranteris, Rugivestis, Spinomarginifera, Thamnosia, Tetracamera, and Tubersulculus (Table 4). Although some genera were common to the Tethys Realm, the Yukon–Pechora Province is assigned to the Boreal Realm, based on the presence of genera in this province, characteristic of the Boreal Realm.

The Mongolia–Okhotsk Province was characterized by Eumetria, Flexaria, Fusella, Jilinmartinia, Kasakhstania, Ombonia, Peniculauris, and Spirelytha (Table 4). These genera were also the characteristic genera of the Central Asia Region.

All of the characteristic genera of the above three provinces, and the genera that are common to two or three of these three provinces, such as Alispirifer, Attenuatella, Jakutoproductus, Lanipustula, Orulgania, Paeckelmanella, Plicatiferina, Praehorridonia, Rotaia, Semicostella, Spinomarginifera, Strophalosia, Spiriferinaella, Taimyrella, Verkhotomia, Yakovlevia, and Zaissania, comprised the characteristic genera of the Boreal Realm. In addition, some genera with a bipolar distribution are important for identification of the Boreal Realm, such as Lanipustula, Tomiopsis and Trigonotreta.

2.2.2 Tethys Realm

The Tethys Realm can be divided into the Southern North America–Northern South America Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Southern North America–Northern South America Province”) of the West Tethys Region, the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province, the South China Province, and the Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province”) of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region (also called the “East Tethys Region”).

The Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province included many characteristic genera, including Anopliopsis, Aseptella, Caenanoplia, Chonetinella, Drahanorhynchus, Globiella, Globosochonetes, Liosotella, Megachonetes, Paeckelmannia, Plicotorynifer, Purdonella, Pustula, Sergospirifer, Spirigerella, and Tapajotia (Table 4).

It should be noted that a large Pennsylvanian brachiopod fauna in the Cantabrian Mountains of Spain, which contained Anthracospirifer, Crania, and Diplanus, seems to show similarities to brachiopod faunas from the Southern North America–Northern South America Province. However, the abundance of Brachythyrina, Chonetinella, Hemiptychina, Notothyris, Plicatifera, Proboscidella, Psilocamara, Stipulina, etc. indicate that this fauna belonged to the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region, as it was more strongly associated with this region than other regions. Although the Pennsylvanian brachiopod fauna of northern Algeria did not exhibit diverse genera or species, the presence of Choristites, Parachoristites, and Brachythyrina indicates features similar to the brachiopod fauna of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region. Thus, the brachiopod fauna of northern Algeria was temporarily placed in the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province.

Endemic genera of the South China Province included Acosarina, Centronelloidea, and Yanbianella, as well as some characteristic genera (Eliva, Goniophoria, Notothyris, Plicatifera, Psilocamara, and Stipulina) and some familiar genera (Brachythyrina, Buxtonia, Choristites, Echinoconchus, and Marginifera) of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region (Table 4). Therefore, this area should be included in the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region.

The Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province included some endemic genera, such as Enteletina and Rugoconcha. However, the province also included some characteristic genera (Camarophoria, Goniophoria, Hemiptychina, Echinoconchus, Marginifera, Notothyris, Proboscidella, and Spiriferina) and familiar genera (Buxtonia, Choristites, Echinoconchus, and Marginifera) of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region, but without the characteristic genera of the Gondwana Realm (Table 4). We here place this province temporarily in the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region, but the exact palaeobiogeographic affinities should be further investigated because available data are outdated.

The characteristic genera of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Realm included the characteristic genera of the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province, the South China Province, and the Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province, along with other genera that appeared in common in two or three of these provinces, including Camarophoria, Eliva, Goniophoria, Hemiptychina, Notothyris, Plicatifera, Proboscidella, Psilocamara, Spiriferina, and Stipulina. In addition, some genera not limited to the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region appeared at every fossil locality in the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region, such as Brachythyrina, Buxtonia, Choristites, Echinoconchus, and Marginifera; these genera were also important for identifying the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Realm (Table 4).

The Southern North America–Northern South America Province of the West Tethys Region (Wang 1994) included the characteristic genera Choristitella, Cryptacanthia, Derbyoides, Desmoinesia, Dictyoclostus, Eolissochonetes, Leptalosia, Lindstroemella, Lissomarginifera, Poikilosakos, Septospirifer, and Wellerella. Moreover, Anthracospirifer and Crania, although also occurring in Spain, occurred at higher frequencies in North America faunas. No characteristic or common genera (e.g., Brachythyrina, Choristites, Pugnax, and Uncinunellina) of the Palaeo-Tethys Region were present in the Southern North America–Northern South America Province (Table 4). The brachiopod material of northern South America is of poor quality. Thus, additional studies are required to determine if this area should be considered as an independent province.

2.2.3 Gondwana Realm

The Gondwana Realm can be divided into the West Argentina Province of the West Gondwana Region and the Bowen–Sydney Palaeobiogeographic Province (herein “Bowen–Sydney Province”) of the East Gondwana Region.

The characteristic genera of the Bowen–Sydney Province included Auriculispina, Booralia, Licharewia, Liriplica, Lissella, Marginirugus, Marinurnula, Permasyrinx, Spinuliplica, and Yagonia, as well as two genera with a bipolar distribution, Attenuatella, and Trigonotreta. These genera were also characteristic of the East Gondwana Region (Table 4).

Costuloplica, Gonzalezius, Maemia, Torynifer, and Tuberculatella, as well as Lanipustula (a bipolar distribution genera), are characteristic genera of the West Gondwana Region and of the West Argentina Province (Table 4).

The characteristic genera of both the Bowen–Sydney Province and the West Argentina Province, and the common genera in these two provinces (Alispirifer, Levipustula, Syringothyris etc.) made up the characteristic genera of the Gondwana Realm (Table 4).

3 Coevolution of palaeobiogeography and Pangaea

The most important tectonopalaeogeographic event during the Carboniferous was the formation and evolution of Pangaea. Therefore, the coevolution of palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography during this period is mainly represented by the coevolution of palaeobiogeography and Pangaea.

3.1 Coevolution of the Boreal Realm and Pangaea

In the Devonian, the main plates and blocks of the northern continents were still located at middle–low latitudes and the Boreal Realm had not yet formed.

In the Mississippian, the Kolyma–Chukchi Block, the Siberia Plate, the northern margin of the Kazakhstan Plate, and the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block were located at middle latitudes (Scotese and McKerrow 1990; Boucot et al. 2013), and the main plates and blocks of the northern continents were drifting northwards. These plates and blocks were located in cool temperate environments that supported brachiopod faunas adapted to cool water, constituting the formation of the Boreal Realm.

The Siberia Plate acted as a continental barrier, dividing the Boreal Realm into eastern and western parts. The western part developed into the Barents Region while the eastern part developed into the Central Asia Region. The semi-closed Mongolia–Okhotsk Ocean tectonic domain formed in the northeast part of the Boreal Realm. At the southern margin of the Mongolia–Okhotsk Ocean (i.e., at the eastern margin of the Siberia Plate, the northeastern margin of the Kazakhstan Plate, and the northern margin of the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block), the Mongolia–Okhotsk cool-water brachiopod fauna developed and the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province was formed. The Barents Ocean tectonic domain formed in the northwestern part of the Boreal Realm. At the northern margin of the Barents Ocean (i.e., the Kolyma–Chukchi Block and the southwestern margin of the Siberia Plate), the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr brachiopod fauna developed and the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province was formed.

By the Pennsylvanian, the main plates and blocks of the northern continent had continued to shift northwards, the Siberia Plate was in a middle–high latitude zone, and the Yukon in northwestern North America and the Timan–Pechora in the northeast of the Eastern European Plate had entered a mid-latitude zone (Scotese and McKerrow 1990; Boucot et al. 2013). Thus, in addition to the northeastern margin of the Barents Ocean, the southern margin of this ocean also provided conditions conducive to the development of cool-water brachiopod faunas; these faunas became the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province and the Yukon–Pechora Province. During the Pennsylvanian, the Kazakhstan Plate had probably collided with the Siberia Plate, thus strengthening the continental barrier posed by the Siberia Plate.

3.2 Coevolution of the Tethys Realm and Pangaea

One of the most striking features of the Tethys Realm was the differentiation of the Tethys warm-water brachiopod fauna into eastern and western parts. This differentiation is primarily reflected in differences in the brachiopod faunas of North America and Europe–Central Asia. The tectonopalaeogeographic conditions leading to this differentiation started at the end of the Early Paleozoic with the closure of the Iapetus Ocean, which formed the Caledonian Orogenic Belt during amalgamation with North America (Laurentia) and Europe to form Laurussia. The Caledonian Orogenic Belt of Laurussia undoubtedly exerted strong controls on Mississippian marine sediments, which is an important tectonopalaeogeographic basis for the differentiation of brachiopod faunas on the western margin of Laurussia (including the epicontinental sea of central North America) and the eastern margin of Laurussia (including the epicontinental sea of Russia).

During the end of the Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, closure of the Rheic seaway and collision between Gondwana and Laurussia formed the Variscan Orogenic Belt (Golonka and Ford 2000; Vai 2003), which led to the collision of North America of Laurussia and the northern part of South America and Africa of Gondwana, and the formation of the embryonic Pangaea. The “continental barrier” created by North America–South America and the African continents, through the Tethys Realm from north to south, was strong, and the differentiation between eastern and western parts of the Tethys Realm became more clearly demarcated. As a result, the West Tethys Region and the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region (also called the “East Tethys Region”) were formed, respectively.

The Palaeo-Tethys Ocean tectonic domain began to form in the Pennsylvanian. The East European Plate, most of the Kazakhstan Plate, and the southern margin of the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block formed the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean tectonic domain. This domain was located at middle and low latitudes, and was the site of development of the brachiopod fauna on the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean, thus forming the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province. A series of microcontinents along the southern margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean resulted in the development of a warm-water brachiopod fauna, thus forming the Southern Margin of the Tethys Ocean Province. South China and Southeast Asia, which were the locations of the South China brachiopod fauna, were always dissociated from the major continental blocks and were located near the palaeoequator, forming the South China Province. Thus, the vast Palaeo-Tethys Ocean was a significant “ocean barrier” that segmented the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region into different provinces.

3.3 Coevolution of the Gondwana Realm and Pangaea

A coevolutionary relationship developed between the Gondwana Realm and Gondwana. Gondwana formed at the end of the Neoproterozoic, and the main blocks of Gondwana were distributed in Antarctic regions (Crowell 1999). Thus, the Gondwana Realm formed in a cool temperate environment, which prompted the development of a cool-water brachiopod fauna. During the Carboniferous, Gondwana rotated clockwise, with West Gondwana (including South America and Africa) shifting northwards and East Gondwana (India and Australia) shifting southwards relative to one another (Scotese and McKerrow 1990; Boucot et al. 2013). During this rotation, Australia shifted from middle south latitudes to high south latitudes. As a result, the brachiopod fauna of Australia evolved to a cool-water type, and the palaeobiogeographic realm of the area shifted from that of the Tethys Realm to that of the Gondwana Realm.

During the Carboniferous, the main parts of Gondwana, including central and southern Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and East Antarctica, were located at the center of Antarctica, thus playing an important role as a “continental barrier” by dividing the Gondwana Realm into eastern and western regions. The West Argentina cool-water brachiopod fauna developed in the western region and formed the West Argentina Province. In the eastern region, the Himalaya cool-water brachiopod fauna developed during the Mississippian and the Bowen–Sydney cool-water brachiopod fauna developed during the Pennsylvanian; these formed the Himalaya Province and the Bowen–Sydney Province, respectively.

4 Discussion

We choose Mississippian and Pennsylvanian as time bins, rather than stages, because it is sufficient to illustrate the coevolutionary relationship of palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography. If it is analyzed at the stage level, the analysis would be very long and based on selective data. Because it is difficult to ascertain the exact age of each brachiopod fauna, the accuracy of analysis result will be difficult to guarantee after much selections. Anyhow, improving the temporal resolution and discussing coevolutionary relationship at the stage level is the direction of our next study.

The palaeobiogeographic realms, regions and provinces in this paper are based on the appearance of characteristic genera or combination of characteristic genera. It is proved that the method of characteristic genera analysis is simple and practicable, especially in dividing realms. For example, the distribution ranges of different cool-water genera are different in the Boreal Realm. Some cool-water genera, distributed over the Boreal Realm, can be used as a sign to define the realm; some only distributed in one of regions and can be used as a sign to divide regions; and some possibly distributed in one of provinces and can be used as a sign to divide provinces (details see 2.1.1 and 2.2.1). Then, they respectively constitute the characteristic genera of each realm, region and province.

Based on the above comparative analysis of Carboniferous brachiopod palaeobiogeography and the formation and evolution of Pangaea, we found a close relationship between palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeographic patterns. In a sense, the tectonopalaeogeographic environment determined the brachiopod fauna and the corresponding palaeobiogeographic units. We refer to this relationship as a coevolutionary relationship (Wang et al. 2013, 2014, 2015; Li and Wang 2015). Like that, the formation of cool environment of the Boreal Realm, a distributed area of cool-water brachiopods, is controlled by the latitudes. However, the necessary condition for the development of the cool-water brachiopod fauna in the Boreal Realm is the formation of Pangea, in which a variety of plates (Laurussia, Siberia, etc.) were continuously drifting northwards; some plates/blocks entered middle- and high-latitudinal regions and were located in cool climatic environments (Wang et al. 2014).

Through the recent research about the controlling factors of Late Paleozoic brachiopod palaeobiogeography, the authors concluded that: the primary unit (realm) of the brachiopod palaeobiogeography during Carboniferous–Permian could be divided into the Boreal Realm, the Tethys Realm, and the Gondwana Realm, showing a close correspondence with the palaeolatitudes; the secondary unit (region) is mainly controlled by the tectonopalaeogeography, among which the most important factor is the “continental barrier” of Pangea, as a “central axis” continent, during the Carboniferous–Permian; the tertiary unit (province) is often more closely related to the oceanic and continental configuration (tectonopalaeogeographic environment) of a certain region. It is similar with that in the Permian (Wang et al. 2015).

5 Conclusions

-

1)

The brachiopod palaeobiogeography of the Mississippian can be divided into the Boreal Realm, the Tethys Realm, and the Gondwana Realm. The Boreal Realm included the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province of the Barents Region and the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province of the Central Asia Region. The Tethys Realm included the North America Province of the West Tethys Region, and the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province, the South China Province, and the Australia Province of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region. The Gondwana Realm comprised the West Argentina Province of the West Gondwana Region and the Himalaya Province of the East Gondwana Region. During the Pennsylvanian, the Boreal Realm was divided into the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province and the Yukon–Pechora Province of the Barents Region, and the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province of the Central Asia Region. The Tethys Realm developed into the Southern North America–Northern South America Province of the West Tethys Region, thus forming the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean, South China, and Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean provinces of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Region. The Gondwana Realm included the West Argentina Province of the West Gondwana Region and the Bowen–Sydney Province of the East Gondwana Region.

-

2)

During the Mississippian, the Kolyma–Chukchi Block, the Siberia Plate, the Kazakhstan Plate, and the northern margin of the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block entered mid–high latitudes, and were thus located in a cool temperate environment; a cool-water brachiopod fauna developed and the Boreal Realm formed. During the Pennsylvanian, East Gondwana shifted southwards and Australia shifted from middle south latitudes to high south latitudes. The brachiopod faunas in these areas changed from warm-water to cool-water types, and the palaeobiogeography shifted from the Tethys Realm to the Gondwana Realm.

-

3)

The Siberia, Gondwana, and Laurussia continents were distributed along a latitudinal gradient from north to south, from which the Boreal, Tethys, and Gondwana realms developed, respectively, thus forming a clear “continental barrier”, with the effect of geographically isolating the three realms into east and west regions (i.e., forming the six regions in the Carboniferous). During the end of the Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, closure of the Rheic seaway and collision of North America (from Laurussia) and South America and northern Africa (from Gondwana) meant that the “continental barrier” was strengthened and the differentiation between the eastern and western parts of the Tethys Realm became more distinct.

-

4)

In the Barents Ocean tectonic domain, the Verkhoyansk–Taymyr Province formed on the northern margin of the Barents Ocean, and, starting in the Pennsylvanian, the Yukon–Pechora Province formed on the southern margin of the Barents Ocean. In the Mongolia–Okhotsk Ocean tectonic domain, the eastern margin of the Siberia Plate, the northeastern margin of the Kazakhstan Plate, and the northern margin of the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block formed the Mongolia–Okhotsk Province. In the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean tectonic domain, a brachiopod fauna developed on the East Europe Plate, the Kazakhstan Plate, and the southern margin of the Jiamusi–Mongolia Block of the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean, thus forming the Northern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province. On the southern margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean, the Southern Margin of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean Province was composed of brachiopods of a series of micro-blocks. South China and Southeast Asia were dissociated from the major continental blocks, and the South China Province formed in this area.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abramov, B.S., and A.D. Grigoryeva. 1983. Biostratigraphy and brachiopods of the middle and late carboniferous of Verchoyan. Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Paleontologicheskii Institut, Trudy 200: 168 pp. (in Russian).

Abramov, B.S., and A.D. Grigoryeva. 1986. Biostratigraphy and brachiopods of the lower carboniferous of Verchoyan, 192 pp. Moscow: Nauka (in Russian).

Atif, K.F.T., and M. Legrand-Blain. 2011. Appearance of Choristitinae (spiriferide brachiopods) during the early Bashkirian of the Bechar Basin, northwestern Algerian Sahara. Comptes Rendus Palevol 10 (4): 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2011.01.008.

Bamber, E.W., and J.B. Waterhouse. 1971. Carboniferous and Permian stratigraphy and paleontology, northern Yukon territory, Canada. Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology 19 (1): 29–250.

Bassett, M.G., and C. Bryant. 2006. A Tournaisian brachiopod fauna from south-east Wales. Palaeontology 49 (3): 485–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00551.x.

Beus, S.S., and N.G. Lane. 1969. Middle Pennsylvanian fossils from Indian Springs, Nevada. Journal of Paleontology 43: 986–1000.

Bottjer, D.J. 2005. Geobiology and the fossil record: Eukaryotes, microbes, and their interactions. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 219 (1–2): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.011.

Boucot, A.J., X. Chen, C.R. Scotese, and R.J. Morley. 2013. Phanerozoic paleoclimate: An atlas of lithologic indicators of climate. In SEPM concepts in sedimentology and paleontology, no. 11, 484 pp. https://doi.org/10.2110/sepmcsp.11.

Bozkurt, E., M.F. Pereira, R. Strachan, and C. Quesada. 2008. Evolution of the Rheic Ocean. Tectonophysics 461 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2008.08.015.

Brew, D.C., and S.S. Beus. 1976. A middle Pennsylvanian fauna from Naco Formation near Kohl Ranch, central Arizona. Journal of Paleontology 50: 888–906.

Brunton, C.H.C. 1966. Silicified Productoids from the Visean of County Fermanagh. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology 12: 175–243, pls. 1–19.

Brunton, C.H.C. 1968. Silicified productoids from the Visean of County Fermanagh (II). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology 16: 1–70, pls. 1–9.

Campbell, K.S.W. 1956. Some carboniferous productid brachiopods from New South Wales. Journal of Paleontology 30: 463–480.

Campbell, K.S.W. 1957. A lower carboniferous brachiopod–coral fauna from New South Wales. Journal of Paleontology 31 (1): 34–98, pls. 11–17.

Campbell, K.S.W. 1961. Carboniferous fossils from the Kuttung rocks of New South Wales. Palaeontology 4: 428–474, pls. 53–63.

Campbell, K.S.W., and J. Roberts. 1964. Two species of Delepinea from New South Wales. Palaeontology 7: 514–524, pls. 80–82.

Carter, J.L. 1967. Mississippian brachiopods from the Chappel limestone of central Texas. Bulletin of American Paleontology 53 (238): 253–488, pls. 13–45.

Carter, J.L. 1968. New genera and species of early Mississippian brachiopods from the Burlington limestone. Journal of Paleontology 42 (5): 1140–1152.

Carter, J.L. 1972. Early Mississippian branchiopods from the Gilmore city limestone of Iowa. Journal of Paleontology 46 (4): 473–491.

Carter, J.L. 1987. Lower Carboniferous brachiopods from the Banff formation of western Alberta. Geological Survey of Canada, Bulletin 378: 1–183.

Carter, J.L. 1988. Early Mississippian brachiopods from the Glen Park Formation of Illinois and Missouri. Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 27: 1–82.

Chen, Z.Q., and N.W. Archbold. 2000. Tournaisian–Visean brachiopods from the Gancaohu area of southern Tienshan Mountains, Xinjiang, NW China. Geobios 33 (2): 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(00)80015-7.

Chen, Z.Q., and G.R. Shi. 2000. Bashkirian to Moscovian (late Carboniferous) brachiopod faunas from the western Kunlun Mountains, Northwest China. Geobios 33 (5): 543–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(00)80027-3.

Chen, Z.Q., J.I. Tazawa, G.R. Shi, and N.S. Matsuda. 2005. Uppermost Mississippian brachiopods from the basal Itaituba formation of the Amazon Basin, Brazil. Journal of Paleontology 79 (5): 907–926. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[0907:UMBFTB]2.0.CO;2.

Cisterna, G.A., and A.F. Sterren. 2016. Late Carboniferous postglacial brachiopod faunas in the southwestern Gondwana margin. Palaeoworld 25 (4): 569–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palwor.2016.07.005.

Crowell, J.C. 1999. Pre-Mesozoic ice ages: their bearing on understanding the climate system. GSA Memoir 192: 1–106.

Cvancara, A.M. 1958. Invertebrate fossils from the lower Carboniferous of New South Wales. Journal of Paleontology 32 (5): 846–888.

Ding, P.Z. 1985. The reidentifications of early Carboniferous Syringothyridids fossils from Ejin Qi of Inner Mongol Autonomous Region and its significance. Bulletin of Xi’an Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences 11: 75–84, pls. 1–3 (in Chinese).

Dunbar, C.O., and G.E. Condra. 1932. Brachiopoda of the Pennsylvanian system in Nebraska. Bulletin of the Nebraska Geological Survey, Ser. 2 5: 1–377, pls. 1–44.

Gaetani, M., A. Zanchi, L. Angiolini, G. Olivini, D. Sciunnach, H. Brunton, A. Nicora, and R. Mawson. 2004. The Carboniferous of the western Karakoram (Pakistan). Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 23 (2): 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1367-9120(03)00137-8.

Galitzkaja, A.Y. 1977. Early and middle Carboniferous Productida of northern Kirghizia, 298 pp. Frunze: Akademiia Nauk Kirgizkoi SSSR (in Russian).

Golonka, J., and D. Ford. 2000. Pangean (late Carboniferous–middle Jurassic) paleoenvironment and lithofacies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 161 (1–2): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00115-2.

Grechishnikova, I.A., and E.S. Levitskii. 2011. The Famennian–Lower Carboniferous reference section Geran-Kalasi (Nakhichevan Autonomous Region, Azerbaijan). Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 19 (1): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0869593811010035.

Gretchishnikova, I.A. 1966. Stratigraphy and Brachiopods of the Lower Carboniferous of the Rudny Altai, 184 pp. Moscow: Publishing Office Science (in Russian).

He, X.L., M.L. Zhu, B.H. Fan, S.Q. Zhuang, H. Ding, and Q.Y. Xue. 1995. The late paleozoic stratigraphic classification, correlation and biota from Eastern Hill of Taiyuan City, Shanxi Province. Changchun: Jilin University Press (in Chinese with English Summary).

Hoare, R.D. 1960. New Pennsylvanian Brachiopoda from Southwest Missouri. Journal of Paleontology 34 (2): 217–232.

Hoare, R.D., and J.D. Burgess. 1960. Fauna from the Tensleep sandstone in Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 34 (4): 711–716.

Isaacson, P.E., and J.T. Dutro. 1999. Lower Carboniferous brachiopods from Sierra de Almeida, northern Chile. Journal of Paleontology 73 (4): 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000032443.

Ivanova, E.A., M.N. Solovieva, and E.M. Shik. 1979. The Moscovian Stage in the USSR and throughout the world. In The Carboniferous of the USSR, ed. R.H. Wagner, A.C. Higgins, and S.V. Meyen. Yorkshire Geological Society Occasional Publication, vol. 4, pp. 117–146.

Jastrzębski, M., A. Żelaźniewicz, J. Majka, M. Murtezi, J. Bazarnik, and I. Kapitonov. 2013. Constraints on the Devonian–Carboniferous closure of the Rheic Ocean from a multi-method geochronology study of the Staré Město Belt in the Sudetes (Poland and the Czech Republic). Lithos 170–171: 54–72.

Jin, Y.G., and D.L. Sun. 1981. Paleozoic brachiopods from Xizang. In Palaeontology of Xizang, Book 3, ed. Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Chinese Academy of Sciences, pp. 127–176. Beijing: Science Press (in Chinese).

Kalashnikov, N.V. 1980. Brachiopods of the Upper Palaeozoic from European part of USSR. Leningrad: Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Komi Filial Institut Geologii (in Russian).

Kora, M. 1995. Carboniferous macrofauna from Sinai, Egypt: Biostratigraphy and palaeogeography. Journal of African Earth Sciences 20 (1): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-5362(95)00043-S.

Kotlyar, G.V. 2002. Brachiopods. In Paleontology Atlas of Zabaykal’ye, ed. A.V. Kurilenko, G.V. Kotlyar, and N.P. Kulkov, pp. 220–249, 298–310. New Siberian: Science Press (in Russian).

Lane, N.G. 1963. A silicified Morrowan brachiopod faunule from the Bird Spring Formation, southern Nevada. Journal of Paleontology 37 (2): 379–392.

Lee, L., and F. Gu. 1980. The brachiopod (Carboniferous–Permian Part). In Paleontological Atlas of Northeast China (Palaeozoic volume), ed. Shenyang Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, pp. 327–428. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Legrand-Blain, M. 1985. North Africa Brachiopod. In The Carboniferous of the World: II. Australia, Indian Subcontinent, South Africa, South America and North Africa, ed. H.W. Robert, pp. 372–374. IUGS Publication 20.

Li, N., and C.W. Wang. 2015. Coevolution between brachiopod paleobiogeography of central Jilin and environment during the Late Paleozoic. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 54 (2): 250–260 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liao, Z.T., and R.J. Zhang. 2006. Early Carboniferous brachiopods from Jinbo of Baisha county, Hainan Island. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 45 (2): 153–174 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Lieberman, B.S. 2005. Geobiology and paleobiogeography: Tracking the coevolution of the earth and its biota. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 219 (1–2): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.012.

Litvinovich, N.V. 1962. Carboniferous and Permian deposits of the Western region of Central Kazakhstan. Moscow: Mosk Gos Univ (in Russian).

Liu, F. 1987. The discovery of brachiopod fossils from lower part of Benxi Formation (mid-Carboniferous), Liaoning province and its significance. Journal of Changchun College of Geology 17 (2): 121–130, 154 pls. 1–2 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, F. 1988. Tournaisian brachiopod fossils from central Jilin province. Journal of Changchun University of Earth Science 18 (4): 361–370, 440 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, Z.H., Z.X. Tan, and Y.L. Ding. 1982. Brachiopoda. In The Palaeontological Atlas of Hunan, ed. Geological Bureau of Hunan, pp. 125–159, 172–216. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Martínez Chacón, M.L., and C.F. Winkler Prins. 1977. A Namurian brachiopod fauna from Meré (province of Oviedo, Spain). Scripta Geologica 39: 1–67.

Martínez Chacón, M.L., and C.F. Winkler Prins. 1979. The brachiopod fauna of the San Emiliano Formation (Cantabrian Mountain, NW Spain) and its connection with other areas. In Neuvième Congrès International de Stratigraphie et de Géologie du Carbonifère, Washington and Champaign-Urbana, Compte Rendu, ed. J.T. Dutro and H.W. Pfefferkorn, vol. 5, pp. 233–244. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Martínez Chacón, M.L., and C.F. Winkler Prins. 2005. Rugosochonetidae (Brachiopoda, Chonetidina) from the Carboniferous of the Cantabrian Mountains (N Spain). Geobios 38 (5): 637–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2004.03.004.

Martínez Chacón, M.L., and C.F. Winkler Prins. 2015. Late Bashkirian–early Moscovian (Pennsylvanian) Productidae (Brachiopoda) from the Cantabrian Mountains (NW Spain). Geobios 48 (6): 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2015.07.007.

Maxwell, W.G.H. 1960. Tournaisian Brachiopods from Baywulla, Queensland. Papers (University of Queensland. Department of Geology) 5 (8): 3–11.

Maxwell, W.G.H. 1961. Lower Carboniferous brachiopod faunas from Old Cannindah, Queensland. Journal of Paleontology 35 (1): 82–103.

McGugan, A., and R. May. 1965. Biometry of Anthracospirifer curvilateralis (Easton) from the Carboniferous of Southeast British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Paleontology 39 (1): 31–40.

Mergl, M., D. Massa, and B. Plauchut. 2001. Devonian and Carboniferous brachiopods and bivalves of the Djado sub-basin (North Niger, SW Libya). Journal of the Czech Geological Society 46 (3–4): 169–188.

Mironova, M.G. 1967. Late Carboniferous brachiopods from Bashkiria. Leningrad: Leningrad University Publishing House (in Russian).

Muir-Wood, H.M. 1948. Malayan lower Carboniferous fossils and their bearing on the Visean Palaeogeography of Asia. London: British Museum (Natural History).

Nalivkin, D.V. 1979. Brachiopods of the Tournaisian of the Urals. Leningrad: Nauka (in Russian).

Nance, R.D. 2010. The Rheic Ocean: Palaeozoic evolution from Gondwana and Laurussia to Pangaea — Introduction. Gondwana Research 17 (2–3): 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2009.12.001.

Navarro-Santillán, D., F. Sour-Tovar, and E. Centeno-García. 2002. Lower Mississippian (Osagean) brachiopods from the Santiago Formation, Oaxaca, Mexico: stratigraphic and tectonic implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 15 (3): 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-9811(02)00047-0.

Nelzina, Р.E. 1965. Middle and Upper Carboniferous Brachiopods and Pelecypods from Onega. Leningrad: Nedra Publishing House (in Russian).

Newell, N.D., J. Chronic, and T.G. Roberts. 1953. Upper Paleozoic of Peeru. Geological Society of America Memoir 58: 1–276. https://doi.org/10.1130/MEM58-p1.

Noffke, N. 2005. Geobiology–a holistic scientific discipline. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 219 (1–2): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.010.

Paeckelmann, W. 1931. Die Brachiopoden des durschen Unterkarbons, Teil 2: Die Productina und Productus-ähnlichen Chonetinae. Abhandlungen Preussische Geologichen Landesanstalt, Neue Folge Heft 136: 1–440, pls. 1–41.

Pérez-Huerta, A. 2006. Pennsylvanian brachiopods of the Great Basin (USA). Palaeontographica Abteilung A 275 (4–6): 97–169.

Prokofev, V.A. 1975. Late Carboniferous Brachiopods from Samara. Moskva: Nedra Publishing House (in Russian).

Qiao, L., M. Falahatgar, and S.Z. Shen. 2017. A lower Viséan (Carboniferous) brachiopod fauna from the eastern Alborz Mountains, northern Iran, and its palaeobiogeographical implications. Geological Journal 52 (2): 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.2759.

Qiao, L., and S.Z. Shen. 2014. Global paleobiogeography of brachiopods during the Mississippian — Response to the global tectonic reconfiguration, ocean circulation, and climate changes. Gondwana Research 26 (3–4): 1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2013.09.013.

Reed, F.R.C. 1925. Upper Carboniferous fossils from Chitral and the Pamirs. Palaeontologia Indica, new series, Memoir 4 (6): 1–134.

Reed, F.R.C. 1931. Upper Carboniferous fossils from Afghanistan. Palaeontologia Indica, new series, Memoir 19: 1–39.

Roberts, J. 1964. Lower Carboniferous brachiopods from Greenhills, New South Wales. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia 11 (2): 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167616408728570.

Roberts, J. 1971. Devonian and Carboniferous brachiopods from the Bonaparte Gulf Basin, northwestern Australia. Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics 122: 1–319.

Roberts, J., J.W. Hunt, and D.M. Thompson. 1976. Late Carboniferous marine invertebrate zones of eastern Australia. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 1 (2): 197–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/03115517608619071.

Rocha Campos, A.C. 1985. Archangelsky South America. In The Carboniferous of the World: II. Australia, Indian subcontinent, South Africa, South America and North Africa, ed. H.W. Robert, pp. 175–298. IUGS Publication 20.

Rodriguez, J., and R.C. Gutschick. 1968. Productina, Cyrtina, and Dielasma (Brachiopoda) from the Lodgepole Limestone (Mississippian) of southwestern Montana. Journal of Paleontology 42 (4): 1027–1032.

Rodriguez, J., and R.C. Gutschick. 1969. Silicified brachiopods from the lower Lodgepole Limestone (Kinderhookian), southwestern Montana. Journal of Paleontology 43 (4): 952–960.

Sarytcheva, T.G. 1968. Upper Palaeozoic brachiopods from west Kazakhstan. Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Paleontologicheskii Institut, Trudy 121: 1–154 (in Russian).

Sarytcheva, T.G., and A.N. Solkolskaya. 1952. A description of the Palaeozoic Brachiopoda of the Moscow Basin. Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Paleontologicheskii Institut, Trudy 38: 1–306 (in Russian).

Sarytcheva, T.G., A.N. Solkolskaya, G.A. Besnosova, and S.V. Maximova. 1963. Carboniferous Brachiopods and Palaeogeography of the Kuznetsk Basin. Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Paleontologicheskii Institut, Trudy 95: 1–547 (in Russian).

Scotese, C.R., and W.S. McKerrow. 1990. Revised world maps and introduction. In Palaeozoic Palaeogeography and Biogeography, ed. W.S. McKerrow and C.R. Scotese, pp. 1–21. Geological Society of London, Memoir 12.

Sour-Tovar, F., F. Álvarez, and L.M.C. María. 2005. Lower Mississippian (Osagean) spire-bearing brachiopods from Cañón De La Peregrina, north of Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, northeastern México. Journal of Paleontology 79 (3): 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079<0469:LMOSBF>2.0.CO;2.

Su, Y.Z., and F. Gu. 1987. Early Carboniferous brachiopods of Beixing Formation in Mishan area, eastern Heilongjiang Province, China. Bulletin of the Shenyang Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences 15: 145–155 (in Chinese).

Sutherland, P.K., and F.H. Harlow. 1967. Late Pennsylvanian brachiopods from north-central New Mexico. Journal of Paleontology 41 (5): 1065–1089.

Taboada, A.C. 2010. Mississippian–early Permian brachiopods from western Argentina: tools for middle- to high-latitude correlation, paleobiogeographic and paleoclimatic reconstruction. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 298 (1–2): 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.07.008.

Thomas, G.A. 1971. Carboniferous and early Permian brachiopoda from Western and North Australia. Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, Bulletin 56: 1–26.

Tong, Z.X., J.R. Chen, Y.Z. Qian, Y. Shi, and Y.T. Pan. 1990. Carboniferous and early early Permian stratigraphy and Palaeontology of Waluo district, Yanbian County, Sichuan province, China. Chongqing: Chongqing Publishing House (in Chinese).

Torres-Martínez, M.A., F. Sour-Tovar, S. González-Mora, and R. Barragán. 2018. Carboniferous brachiopods (Productida and Orthotetida) from Santiago Ixtaltepec, Oaxaca, southern Mexico. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 21 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.4072/rbp.2018.1.01.

Ustritsky, V.I. 1960. Stratigraphy and faunas of Carboniferous–Permian from the western Kunlun Mountains. Professional Papers of Institute of Geology, Geology and Mineral Resources Minister, China, Series B 5 (1): 1–132, pls. 1–25 (in Chinese).

Ustritsky, V.I., and G.E. Chernyak. 1963. Biostratigraphy and brachiopods of the upper Palaeozoic of Taimyr. Nauchno-Issledovatel’skogo Institut Geologii Arktiki, Trudy 134: 1–139 (in Russian).

Vai, G.B. 2003. Development of the palaeogeography of Pangaea from late Carboniferous to early Permian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 196 (1–2): 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00316-X.

Wang, C.W. 1994. Late Carboniferous brachiopod palaeobiogeographical realm. Jilin Geology 13 (1): 14–23 (in Chinese).

Wang, C.W., N. Li, P. Zong, and Y.Q. Mao. 2014. Coevolution of brachiopod Boreal Realm and Pangea. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 412: 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.07.035.

Wang, C.W., Y.Q. Mao, N. Li, and P. Zong. 2015. Coevolution of brachiopod paleobiogeography and tectonopaleogeography during the early–middle Permian. Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition 89 (6): 1797–1812.

Wang, C.W., and S.P. Yang. 1998. Brachiopods and biostratigraphy of late Carboniferous – early Permian in the middle Xinjiang. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Wang, C.W., G.W. Zhao, N. Li, and P. Zong. 2013. Coevolution of brachiopod paleobiogeography and tectonopaleogeography during the late Paleozoic in Central Asia. Science China Earth Sciences 56 (12): 2094–2106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-013-4670-x.

Wang, S.M. 1984. Brachiopoda. In The Palaeontological Atlas of Hubei province, ed. Regional Geological Surveying Team of Hubei, pp. 128–236, pls. 62–95. Wuhan: Hubei Science and Technology Press (in Chinese).

Waterhouse, J.B. 1966. Lower Carboniferous and upper Permian brachiopods from Nepal. Geologische Bundesanstalt, Jahrbuch 12: 5–99.

Waterhouse, J.B. 1987. Late Palaeozoic Brachiopoda (Athyrida, Spiriferida and Terebratulida) from the southeast Bowen Basin, East Australia. Palaeontographica Abteilung A A196 (1–3): 1–56.

Watkins, R. 1974. Carboniferous brachiopods from northern California. Journal of Paleontology 48 (2): 304–325.

Weller, S. 1905. The northern and southern Kinderhook faunas. The Journal of Geology 13 (7): 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1086/621260.

Weller, S. 1914. The Mississippian Brachiopoda of the Mississippi Valley basin plates. Illinois State Geological Survey, Monograph 1.

Winkler Prins, C.F. 1971. Connections of the Carboniferous brachiopod faunas of the Cantabrian Mountains (Spain). In The Carboniferous of Northwest Spain, part II, ed. R.H. Wagner, pp. 687–694. Trabajos de Geologia, Universidad de Oviedo 4.

Winkler Prins, C.F. 2007. The role of Spain in the development of the reef brachiopod faunas during the Carboniferous. In Biogeography, time, and palace: distributions, barriers, and islands, ed. W. Renema, pp. 217–246. Topics in Geobiology 29.

Yang, F.Q. 1988. Carboniferous. In Palaeobiogeography of China, ed. H.F. Yin, pp. 151–175. Wuhan: China University of Geosciences Press (in Chinese).

Yang, S.P. 1964a. The lower and middle Carboniferous brachiopods from the Northern slope of the mountain Borohoro, Xinjiang. Beijing: Science Press (in Chinese).

Yang, S.P. 1964b. The Tournaisian brachiopods from the southern Guizhou. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 12 (1): 82–110 (in Chinese and in Russian).

Yang, S.P. 1978. Lower Carboniferous brachiopods of Guizhou province and their stratigraphic significance. In Professional papers of stratigraphy and palaeontology (Beijing) 5, pp. 78–142. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Yang, S.P. 1983. Brachiopod biogeographic divisions of the early Carboniferous in China. In Palaeobiogeographic Flora in China, ed. The Editorial Committee of a Series of Books for Paleontologic Basic Theories, pp. 64–73. Beijing: Science Press (in Chinese).

Yang, S.P. 1990. On the biogeographical provinces of early Carboniferous Brachiopoda in China and its adjacent regions. In Tectonopalaeogeography and palaeobiogeography of China and adjacent regions, ed. H.Z. Wang, S.N. Yang, and B.P. Liu, pp. 317–335. Wuhan: China University of Geosciences Press (in Chinese with English Abstract).

Yang, S.P., and Y.N. Fan. 1982. Carboniferous strata and fauna in Shenzha district, northern Xizang (Tibet). In Contribution to the Geology of the Qinghai–Xizang (Tibet) Plateau 10, pp. 46–69. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang, S.P., and Y.N. Fan. 1983. Carboniferous branchiopods from Xizang (Tibet) and their faunal provinces. In Contribution to the geology of the Qinghai–Xizang (Tibet) Plateau 11, pp. 265–285. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Yang, Z.Y., P.C. Ding, H.F. Yin, S.X. Zhang, and J.S. Fan. 1962. The brachiopod fauna of Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic in the Chilianshan region. In Monograph of the Geology of the Chilianshan Mountain 4. Beijing: Science Press (in Chinese).

Zhan, L.P., J.X. Yao, Z.S. Ji, and G.C. Wu. 2007. Late Carboniferous–early Permian brachiopod fauna of Gondwanic affinity in Xainza County, northern Tibet, China: revisited. Geological Bulletin of China 26 (1): 54–72 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, C., F.M. Zhang, Z.X. Zhang, and Z. Wang. 1983. Brachiopods. In Palaeontological Atlas of Northwestern China (Xinjiang Part), Paleozoic Part 2, ed. Regional Geological Survey Team of Xinjiang, Institute of Geosciences of Xinjiang, Geological Survey Group of Petroleum Bureau of Xinjiang, pp. 262–385, pls. 86–145. Beijing: Geological Publishing House (in Chinese).

Zhang, S.X., and Y.G. Jin. 1976. Late Paleozoic brachiopods from the Mount Jolmo Lungma region. In A report of scientific expedition in the Mount Jolmo Lungma region (1966–1968), Palaeobios 2, ed. The Team of Scientific Expedition to Tibet, Chinese Academy of Sciences, pp. 159–271. Beijing: Science Press (in Chinese with English summary).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments that significantly improved the text.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41702011 and Grant No. 41372019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. CWW conceived the idea of the study and directed the analysis. PZ interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. YQM analyzed data and drew the illustrations. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table.

Brachiopods genera of each location during Mississippian and Pennsylvanian.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Wang, CW., Zong, P. et al. Coevolution of global brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography during the Carboniferous. J. Palaeogeogr. 10, 18 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00095-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00095-z