Abstract

Olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) is the major species developed for aquaculture in South Korea. Over the long history of olive flounder aquaculture, complex and diverse diseases have been a major problem, negatively impacting industrial production. Vibriosis is a prolific disease which continuously damages olive flounder aquaculture. A bacterial disease survey was performed from January to June 2017 on 20 olive flounder farms on Jeju Island. A total of 1710 fish were sampled, and bacteria from the external and internal organs of 560 fish were collected. Bacterial strains were identified using 16 s rRNA sequencing. Twenty-seven species and 184 strains of Vibrio were isolated during this survey, and phylogenetic analysis was performed. Bacterial isolates were investigated for the distribution of pathogenic and non-pathogenic species, as well as bacterial presence in tested organs was characterized. V. gigantis and V. scophthalmi were the dominant non-pathogenic and pathogenic strains isolated during this survey, respectively. This study provides data on specific Vibrio spp. isolated from cultured olive flounder in an effort to provide direction for future research and inform aquaculture management practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) is an important aquaculture species in South Korea. In 2016, annual production reached 40,000 tons and constituted 51.9% of the total aquaculture production on Jeju Island alone (Kim 2017). After the establishment of brood stock management in the 1980s, the development and improvement of breeding skills have led to a sharp increase in aquaculture production. However, as a result of enlarged aquaculture industry, recessive seed production, and disease emergence, diverse disease patterns have been observed in cultured olive flounder. In the past, olive flounder disease was affected by high water temperature and singular infection by either bacteria, viruses, or parasites (Kim et al. 2006). Recently, disease patterns have shown co-infection by bacteria, viruses, and parasites, which have led to mass mortality and caused difficulty in disease diagnosis (Cho et al. 2008).

Edwardsiellosis, streptococcosis, and vibriosis are the main bacterial diseases occurring in cultured olive flounder (Cho et al. 2008). Vibriosis is caused by the genus Vibrio, a facultatively anaerobic, oxidase-positive, gram-negative bacilli. Many species in this genus require salt for growth. More than 100 Vibrio spp. have been reported and are predominantly associated with a variety of marine, estuarine, or other aquatic habitats (Janda et al. 2015). Although Vibrio spp. are known to cause disease in humans, animals, and marine organisms, it is understood that only limited Vibrio species, such as V. anguillarum, V. harveyi, and V. ordali, are responsible for causing infection (Janda et al. 2015). The well-known clinical signs of vibriosis are hemorrhagic septicemia, lethargy, weight loss, and dark skin lesions. Previous studies have reported that olive flounder mortality caused by bacterial disease was 6.75%. In 6.75% cases of infection, vibriosis-related mortality was reported in 24.2% (Jee et al. 2014). In olive flounder, Vibrio spp. were the most dominant bacteria isolated from the samples collected between 2007 and 2011 (Cho et al. 2008; Jung et al. 2012). Given the long history of olive flounder aquaculture, many epidemiological surveys have been conducted for the purpose of monitoring disease outbreak (Choi et al. 2010; Jung et al. 2006; Kim 2002; Oh et al. 1998; Park et al. 2016, 2009).

Bacterial identification previously relied on sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (Frans et al. 2011; Bjelland et al. 2012; Jensen et al. 2003; Terceti et al. 2016; Wiik et al. 1995). However, species identification relying on 16S rRNA gene sequencing may not guarantee accuracy, thereby leading to the necessity of utilizing software such as EzBioCloud (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/). EzBioCloud search tools support genomic data with taxonomic identification at genus, species, or subspecies levels (Yoon et al. 2017).

In this study, we investigated bacterial diseases in cultured olive flounder and identified Vibrio spp. using EzBioCloud. We hypothesize the variety of Vibrio sp. collected and consistent colonization patterns in organ tissues of olive flounder. Also, few characteristics of isolated Vibrio species are provided in the results of this paper.

Materials and methods

Fish samples

The bacterial disease survey was conducted from January 2017 to June 2017. Investigations were performed at the olive flounder farms in Seongsan, Pyoseon/Namwon, Daejeong/Hangyeong, and Gujwa/Jocheon (Fig. 1). A total of 1710 olive flounder samples were obtained from 20 fish farms, and fish samples included fry (total length 8–16 cm), juveniles (total length 22–37 cm), and adults (total length over 50 cm). Five hundred seventy fish were randomly selected for bacterial isolation.

Bacterial isolation

Bacteria were isolated from gill, intestine, kidney, and liver tissues and incubated on a brain-heart infusion agar plate (BHIA) supplemented with 1% NaCl at 25 °C for 48 h. Secondary culture was performed for specific bacterial isolation. Isolated bacteria were stored at − 50 °C using BHIA broth supplemented with 1% NaCl and containing a total concentration of 20% glycerol for future use.

Isolation of Vibrio spp. and 16S rRNA analysis

Bacterial stocks were cultured in BHIA agar supplemented with 1% NaCl for 48 h. Cultured plates were sent to Macrogen for 16S rRNA sequencing (Seoul, South Korea). The 16S rRNA sequences were merged using Unipro UGENE software version 1.29, and bacterial strains were identified using EzBioCloud (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/) (Yoon et al. 2017). We selected Vibrio spp. from among the identified bacteria using the sequencing results and further divided the Vibrio spp. into pathogenic and non-pathogenic species based on the previous literature. The distribution of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Vibrio spp. was investigated by monthly period and isolated by the organ they were collected from. In addition, the distribution of dominant Vibrio spp. was investigated. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using Molecular Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 7.0 (Kumar et al. 2016), by neighbor-joining method to determine the differences between other bacterial species present and the relationships within Vibrio spp. Bootstrap value was calculated from 1000 replicates.

Results

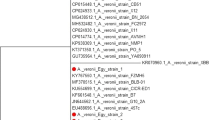

We identified Vibrio spp. among the bacteria isolated from cultured olive flounder in Jeju Island, South Korea (Fig. 1). A total of 26 Vibrio spp. and 184 strains were identified by 16S rRNA sequencing and utilizing the EzBioCloud search tool. Fifteen non-pathogenic and 11 pathogenic Vibrio spp. were isolated from gill, intestine, kidney, and liver tissues. Non-pathogenic species were mostly isolated from gill and skin tissue; pathogenic species isolated from the intestine were present in high numbers (Tables 1 and 2). V. gigantis was the dominant isolate among non-pathogenic species, detected in high levels in gill tissues. V. scophthalmi was the dominant isolate among the pathogenic species; thirty-six isolates from the intestine and 29 isolates from the gill were collected (Fig. 2). Non-pathogenic species showed the highest number of isolates in March. On the other hand, pathogenic species showed an increasing number of isolates throughout the period, except in April, which showed a small number of isolates (Fig. 3). V. gigantis (30 strains) and V. scophthalmi (88 strains) were the dominant species of all Vibrio sampled. V. scophthalmi showed a continuous increase in isolate numbers during this study (Fig. 4). The phylogenetic tree showed a distinct difference between the other bacterial genera present (Fig. 5); certain species were grouped with a specific clade or with the same species, whereas V. maritimus, V. variabilis, V. vulnificus, V. jasicida, V. alginolyticus, and V. sagamiensis showed uncertain grouping.

Discussion

Isolated Vibrio strains were divided into two groups, non-pathogenic and pathogenic species. Most non-pathogenic species were isolated from gill (37 strains) and skin (14 strains) tissue. Within the isolated species, V. gigantis was dominant. V. gigantis was originally isolated from oyster species; Faury et al. (2004) reported it was isolated from Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) hemolymph. Currently, the pathogenicity of V. gigantis is either unreported or unknown. Previous studies have mentioned that is related to bioluminescent features. However, not all strains of V. gigantis possess this feature, suggesting that it may differ based on strain isolation location and relationship with NaCl concentration in the environment (Omeroglu and Karaboz 2012). Other non-pathogenic species were mainly isolated from external organs. Although pathogenicity was uncertain, Vibrio sp. is considered a bacterial flora. As our results have shown numerous isolates in external organs such as gills and skin, these Vibrio spp. are thought to exist ubiquitously in the marine environment and further investigation is needed to specify pathogenicity and biological characteristics.

Within pathogenic species, isolated organ distribution has shown primary isolation from gill (78 strains) and intestinal (44 strains) tissue. The dominant pathogenic species, V. scophthalmi, was first isolated from the intestine of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) in Spain (Cerda Cuellar et al. 1997). It was also isolated from reared clams, olive flounder, summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus), and common dentex (Dentex dentex) (Beaz Hidalgo et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2013; Qiao et al. 2013). Pathogenicity of V. scophthalmi in turbot has been associated with ascites disease, including liver and splenic hemorrhage (Qiao et al. 2013). V. scophthalmi pathogenicity in olive flounder was described as an opportunistic pathogen, showing clinical signs under certain conditions such as stress (Qiao et al. 2012). V. scophthalmi was also reported to occur in relation to V. ichthyoenteri, a causative agent of intestinal necrosis and bacterial enteritis in olive flounder (Ishimaru et al. 1996; Kim 2002). Our results have shown that V. scophthalmi has a high specificity for colonizing intestinal tissue due to the number of strains isolated from that area. In this study, the number of V. scophthalmi was elevated compared to other Vibrio spp., possibly indicating that V. scophthalmi may display a physiological relationship with olive flounder. As Vibrio spp. are ubiquitously found in cultured olive flounder, this topic requires further research.

Vibrio harveyi is a significant pathogen against marine vertebrates and invertebrates and also has a relationship in quorum-sensing (Austin and Zhang 2006; Lago et al. 2009; Li et al. 2011). It has been isolated from many species and identified as a cause of disease or mass mortality in its host. Our results showed the isolation of six strains of V. harveyi distributed throughout the gills, intestines, and kidneys. Although it is considered a main cause of mass mortality and vibriosis in olive flounder on Jeju Island, the number of isolates was comparatively low.

V. tapetis subsp. tapetis is known as the causative agent of epizootic Brown Ring Disease (BRD) infection in adult clams and exhibits shell deformation, growth reduction, and an organic brown deposit on the shell inner surface (Borrego et al. 1996). Jensen et al. (2003) suggested that this species may affect mortality rates in marine vertebrates by showing pathogenicity against corkwing wrasse (Symphodus melops), which could indicate the potential for displaying disease symptoms in olive flounder. Previous studies have shown that V. tapetis subsp. tapetis was closely associated with hemolymph, which functions to transport oxygen in bivalves and crustaceans. Our results have shown that V. tapetis subsp. tapetis was primarily detected in kidney samples. However, our isolated strains were rather small; specific studies are required to consider the influence and the effect may cause against olive flounder.

Other pathogenic species, V. alginolyticus, V. atypicus, V. cortegadensis, V. crassostreae, V. harveyi, V. kanaloe, V. lentus, V. pomeroyi, and V. tapetis subsp. tapetis, have been reported to show pathogenicity in marine organisms; however, there are no conclusive findings regarding their interaction with olive flounder (Borrego et al. 1996; Declercq et al. 2015; Farto et al. 2003; Faury et al. 2004; Lago et al. 2009; Macia et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2010).

Our results showed that gill, intestine, and skin tissues provided the highest levels of isolates within Vibrio spp. Gill and skin tissue supported the highest levels of non-pathogenic species, while pathogenic species were primarily supported by gill and intestinal tissue. Pathogenic species have also shown typical isolation on kidney and liver tissue. Clinical signs observed in olive flounder show a relationship between the loss of body fluid and ascites, which is caused by liver and kidney dysfunction (Mchutchison 1997). We suggest that for the purpose of diagnosing or isolating strains from a sample, organ selection needs to be considered. In order to screen out entire species from the culture environment, external organs such as gills and skin need to be included in the sampling. To target a specific strain which is assumed to have either pathogenic characteristics or to act against resulting pathogenic symptoms, research must focus on the organ targeted by that bacteria, ensuring inclusion of kidney and liver tissues in testing. As many Vibrio spp. have been isolated from cultured olive flounder, multiple past studies have focused on bacterial genus distribution (Cho et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2010, 2006).

Comparison of isolate numbers by month showed that non-pathogenic species had the highest isolate levels in March (17 strains), while other months showed a relatively even number of isolates. With the exception of April (14 strains), the number of isolated pathogenic species increased from month to month. The increase of total numbers of pathogenic isolates may indicate a relationship with water temperature. This is supported by our findings, which showed the highest number of isolates in May and June, indicating that as the water temperature rose, Vibrio spp. distribution in the water also increased and that increased water temperature may act as a causative agent for the spread of disease.

The Vibrio phylogenetic tree showed a distinct difference from other bacterial genera. V. scophthalmi, V. harveyi, V. cortegadensis, V. tapetis subsp. tapetis, V. atlanticus, V. lentus, V. gigantis, V. crassostreae, V. pomeroyi, and V. gallaecicus showed a relationship within strains; however, V. maritimus, V. variabilis, V. vulnificus, V. jasicida, V. alginolyticus, and V. sagamiensis did not show any relationship within the isolates. Previous studies have shown relationships within species, such as Harvey clade or Splendidus clade, which our results have supported (Lasa et al. 2014). 16S rRNA sequences were used to identify specific species and the evolutionary relationship within genus or species (Wiik et al. 1995). However, according to our results, there is difficulty in identifying specific divisions in the same Vibrio sp. using only 16S rRNA sequencing. In previous studies, with a help of other target genes, such as atpA, fstZ, gapA, pyrH, recA, rpoA, rpoD, and topA, few species of Vibrio have shown a consistent group within same species (Balboa and Romalde 2013). For more analysis in Vibrio spp., it is considered that with the help of 16S rRNA genes, other housekeeping genes of Vibrio spp. is required.

Conclusion

A total of 27 species and 184 strains of Vibrio were isolated in this survey. Bacterial isolation patterns differed depending on the organs targeted for sampling. External and internal organs enabled the observation of multiple species. By targeting internal organs, such as the intestine, kidney, and liver, species with pathogenic characteristics were observed. V. gigantis was the dominant isolate among the non-pathogenic species, which was detected at high levels in gill tissues, and V. scophthalmi was the dominant isolate among the pathogenic species, which was found most abundantly in internal organs. Many species identified were not relevant to disease in olive flounder; however, these strains have exhibited pathogenicity in other marine organisms. Although many studies have tried to characterize new Vibrio sp. and bacterial isolates by genus, they lacked species-specific identification. The present study identified specific isolates from Vibrio species for future epidemiological surveys and development of improved disease prevention methods. This study confirmed that a wide variety of Vibrio species are found in cultured olive flounder and indicated that a wider survey range is necessary to mitigate negative impacts on future populations.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the authors for data requests.

Abbreviations

- BHIA:

-

Brain-heart infusion agar

References

Austin B, Zhang XH. Vibrio harveyi: a significant pathogen of marine vertebrates and invertebrates. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43:119–24 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01989.x.

Balboa S, Romalde JL. Multilocus sequence analysis of Vibrio tapetis, the causative agent of Brown Ring Disease: description of Vibrio tapetis subsp. britannicus subsp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:183–7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2012.12.004.

Beaz Hidalgo R, Cleenwerck I, Balboa S, De Wachter M, Thompson FL, Swings J, De Vos P, Romalde JL. Diversity of Vibrios associated with reared clams in Galicia (NW Spain). Syst Appl Microbiol. 2008;31:215–22 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2008.04.001.

Bjelland AM, Johansen R, Brudal E, Hansen H, Winther-Larsen HC, Sørum H. Vibrio salmonicida pathogenesis analyzed by experimental challenge of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Microb Pathog. 2012;52:77–84 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2011.10.007.

Borrego JJ, Castro D, Luque A, Paillard C, Maes P, Garcia MT, Ventosa A. Vibrio tapetis sp. nov., the causative agent of the brown ring disease affecting cultured clams. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:480–4 https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-2-480.

Cerda Cuellar M, Rossello Mora R, Lalucat J, Jofre J, Blanch A. Vibrio scophthalmi sp. nov., a new species from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Int J Syst Bacteriol Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:58–61.

Cho MY, Kim MS, Choi HS, Park GH, Kim JW, Park MS, Park MA. A statistical study on infectious diseases of cultured olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) in Korea. J Fish Pathol. 2008;21:271–8.

Choi HS, Jee B, Cho MY, Park M. Monitoring of pathogens on the cultured Korean rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli) in the marine cages farms of south sea area from 2006 to 2008. J Fish Pathol. 2010;23:27–35.

Declercq AM, Chiers K, Soetaert M, Lasa A, Romalde JL, Polet H, Haesebrouck F, Decostere A. Vibrio tapetis isolated from vesicular skin lesions in Dover sole (Solea solea). Dis Aquat Organ. 2015;115:81–6 https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02880.

Farto R, Armada SP, Montes M, Guisande JA, Pérez MJ, Nieto TP. Vibrio lentus associated with diseased wild octopus (Octopus vulgaris). J Invertebr Pathol. 2003;83:149–56 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2011(03)00067-3.

Faury N, Saulnier D, Thompson FL, Gay M, Swings J, Le Roux F. Vibrio crassostreae sp. nov., isolated from the haemolymph of oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:2137–40 https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.63232-0.

Frans I, Michiels CW, Bossier P, Willems KA, Lievens B, Rediers H. Vibrio anguillarum as a fish pathogen: virulence factors, diagnosis and prevention. J Fish Dis. 2011;34:643–61 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01279.x.

Ishimaru K, Akagawa-Matsushita M, Muroga K. Vibrio ichthyoenteri sp. nov., a pathogen of Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) larvae. Int J Syst Bacteriol Int Union Microbiol Soc. 1996;46:155–9 https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-1-155.

Janda JM, Newton AE, Bopp CA. Vibriosis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35:273–88 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2015.02.007.

Jee BY, Shin KW, Lee DW, Kim YJ, Lee MK. Monitoring of the mortalities and medications in the inland farms of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) in South Korea. J Fish Pathol. 2014;27:77–83.

Jensen S, Samuelsen OB, Andersen K, Torkildsen L, Lambert C, Choquet G, Paillard C, Bergh Ø. Characterization of strains of Vibrio splendidus and V. tapetis isolated from corkwing wrasse (Symphodus melops) suffering vibriosis. Dis Aquat Organ. 2003;53:25–31 https://doi.org/10.3354/dao053025.

Jung SH, Choi H-S, Do J-W, Kim MS, Kwon M-G, Seo JS, Hwang JY, Kim S-R, Cho Y-R, Do Kim J, Park MA, Jee BY, Cho MY, Kim JW. Monitoring of bacteria and parasites in cultured olive flounder, black rockfish, red sea bream and shrimp during summer period in Korea from 2007 to 2011. J Fish Pathol. 2012;25:231–41 https://doi.org/10.7847/jfp.2012.25.3.231.

Jung UW, Kang C, Kim M, Heo M, Oh D, Kang B. Characterization of streptococcosis occurrence and molecular identification of the pathogens of cultured flounder in Jeju Island. Korean J Microbiol. 2006;42:199–204.

Kim D. Pathogenicity of Vibrio ichthyoenteri to olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) larvae. Pukyong Natl Univ. 2002:1–46 http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T8514028.

Kim J. Results of fish culture trends in 2016 (provisional). Stat Korea. 2017. http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1EZ0012&vw_cd=MT_ZTITLE&list_id=F38&seqNo=&lang_mode=ko&language=kor&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=MT_ZTITLE.

Kim JW, Cho MY, Park GH, Won KM, Choi HS, Kim MS, Park MA. Statistical data on infectious diseases of cultured olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) from 2005 to 2007. J Fish Pathol. 2010;23:369–77.

Kim JW, Jung SH, Park MA, Do J, Choi D, Jee B, Cho MY, Kim MS, Choi H, Kim YC, Park M, Lee JS, Lee C, Bang JD, Seo JS. Monitoring of pathogens in cultured fish of Korea for the summer period from 2000 to 2006. J Fish Pathol. 2006;3:207–14.

Kim SH, Woo SH, Lee SJ, Park SI. The infection characteristics of Vibrio scophthalmi isolated from olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). J Fish Pathol. 2013;26:207–17.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4 https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054.

Lago EP, Nieto TP, Seguín RF. Fast detection of Vibrio species potentially pathogenic for mollusc. Vet Microbiol. 2009;139:339–46 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.035.

Lasa A, Diéguez AL, Romalde JL. Vibrio cortegadensis sp. nov., isolated from clams. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105(2):335-41.

Li MF, Wang CL, Sun L. A pathogenic Vibrio harveyi lineage causes recurrent disease outbreaks in cultured Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and induces apoptosis in host cells. Aquaculture. 2011;319:30–6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.06.034.

Macia MC, Ludwig W, Aznar R, Grimont PAD, Schleifer K, Garay E, Pujalte M. Vibrio lentus sp . nov ., isolated from mediterranean oysters. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:1449–56.

Mchutchison JG. Differential diagnosis of ascites. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17:191–202.

Oh S, Kim D, Lee J, Lee C. Bacterial disease outbreak of cultured flounder in Jeju Island(1991 to 1997). J Fish Pathol. 1998;11:23–7.

Omeroglu EE, Karaboz I. Characterization and genotyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of the first bioluminescent Vibrio gigantis strains. African J Microbiol Res. 2012;6:7111–22 https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR12.1775.

Park HK, Jun LJ, Kim SM, Park MA, Cho MY, Don S, Park SH, Do Jeong H, Jeong JB. Monitoring of VHS and RSIVD in cultured Paralichthys olivaceus of Jeju in 2015. Korean J Fish Aquat Sci. 2016;49:176–83.

Park MA, Kim HY, Choi HJ, Jee BY, Cho MY, Lee DC. Survey of Trichodina infection in wild populations of marine fish caught from Namhae region, southen coast of Korea. J Fish Pathol. 2009;22:163–6.

Qiao G, Jang IK, Won KM, Woo SH, Xu DH, Park SI. Pathogenicity comparison of high- and low-virulence strains of Vibrio scophthalmi in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish Sci. 2013;79:99–109 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12562-012-0567-4.

Qiao G, Lee DC, Woo SH, Li H, Xu DH, Park SI. Microbiological characteristics of Vibrio scophthalmi isolates from diseased olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish Sci. 2012;78:853–63 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12562-012-0502-8.

Terceti MS, Ogut H, Osorio CR. Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, an emerging fish pathogen in the Black Sea: evidence of a multiclonal origin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:3736–45 https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00781-16.

Wang Y, Zhang XH, Yu M, Wang H, Austin B. Vibrio atypicus sp. nov., isolated from the digestive tract of the Chinese prawn (Penaeus chinensis O’sbeck). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2517–23 https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.016915-0.

Wiik R, Stackebrandt E, Valle O, Daae FL, Rødseth OM, Andersen K. Classification of fish-pathogenic vibrios based on comparative 16S rRNA analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:421–8 https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-45-3-421.

Yoon SH, Ha SM, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, Chun J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–7 https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001755.

Acknowledgements

This research was a part of the project titled “Fish Vaccine Research Center,” funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HCS obtained the bacterial strains, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. JEK and CNJ conducted the sampling of the fish and diagnosis. JHL supervised the experiment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sohn, H., Kim, J., Jin, C. et al. Identification of Vibrio species isolated from cultured olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) in Jeju Island, South Korea. Fish Aquatic Sci 22, 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-019-0129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-019-0129-0