Abstract

Background

Several studies have highlighted the substantial role of the athlete’s redox and inflammation status during the training process. However, many factors such as differences in testing protocols, assays, sample sizes, and fitness levels of the population are affecting findings and the understanding regarding how exercise affects related biomarkers in adolescent athletes.

Objectives

To search redox homeostasis variables’ and inflammatory mediators’ responses in juvenile athletes following short- or long-term training periods and examine the effect size of those variations to training paradigms.

Methods

A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted. The entire content of PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, and Science Direct were systematically searched until December 2019. Studies with outcomes including (1) a group of adolescent athletes from any individual or team sport, (2) the assessment of redox and/or inflammatory markers after a short- (training session or performance testing) or longer training period, and (3) variables measured in blood were retained. The literature search initially identified 346 potentially relevant records, of which 36 studies met the inclusion criteria for the qualitative synthesis. From those articles, 27 were included in the quantitative analysis (meta-analysis) as their results could be converted into common units.

Results

Following a short training session or performance test, an extremely large increase in protein carbonyls (PC) (ES 4.164; 95% CI 1.716 to 6.613; Z = 3.333, p = 0.001), a large increase in thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) (ES 1.317; 95% CI 0.522 to 2.112; Z = 3.247, p = 0.001), a large decrease in glutathione (GSH) (ES − 1.701; 95% CI − 2.698 to − 0.705; Z = − 3.347, p = 0.001), and a moderate increase of total antioxidant capacity (TAC) level (ES 1.057; 95% CI − 0.044 to 2.158; Z = 1.882, p = 0.060) were observed. Following more extended training periods, GSH showed moderate increases (ES 1.131; 95% CI 0.350 to 1.913; Z = 2.839, p = 0.005) while TBARS displayed a small decrease (ES 0.568; 95% CI − 0.062 to 1.197; Z = 1.768, p = 0.077). Regarding cytokines, a very large and large increase were observed in IL-6 (ES 2.291; 95% CI 1.082 to 3.501; Z = 3.713, p = 0.000) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (ra) (ES 1.599; 95% CI 0.347 to 2.851; Z = 2.503, p = 0.012), respectively, following short-duration training modalities in juvenile athletes.

Conclusions

The results showed significant alterations in oxidative stress and cytokine levels after acute exercise, ranging from moderate to extremely large. In contrast, the variations after chronic exercise ranged from trivial to moderate. However, the observed publication bias and high heterogeneity in specific meta-analysis advocate the need for further exploration and consistency when we deal with the assessed variables to ascertain the implications of structured training regimes on measured variables in order to develop guidelines for training, nutritional advice, and wellbeing in young athletes.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO CRD42020152105

Similar content being viewed by others

Key Points

-

Significant alterations in oxidative stress and cytokines levels are noted after acute exercise, while the variations after chronic exercise ranged from trivial to moderate.

-

The knowledge of the magnitude of those changes could lead to remedies to monitor training, recovery process, nutrition, and athlete’s wellbeing.

-

More randomised control studies (RCTs) and improved study design are primarily recommended to strengthen the quality assessment of relevant investigations and reduce the risk of publication bias and high heterogeneity.

Introduction

Redox homeostasis occurs when a balance between the body’s oxidants and antioxidants exists. On the contrary, an oxidative stress state can indicate a considerable increment of oxidative products or deterioration of various antioxidants to counter the induced stress [1,2,3].

Sports training can lead to significant alterations in variables related to the athlete’s redox and inflammation status [4, 5]. Through sports practice, athletes are regularly exposed to different types of stress to achieve the desired adaptations, which in turn contribute to performance enhancements. Recently, our knowledge about the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) on exercise has expanded. It is now well accepted that training adaptations might also be linked to improvements in metabolic changes influenced by exercise-induced oxidative stress [6,7,8]. Moreover, exercise-induced oxidative stress might display the necessary signalling to determine adaptations to endurance training [6]. Also, initial levels of specific enzymatic antioxidant, like superoxide dismutase (SOD), could be used to predict the capacity of the antioxidant defence system and differentiate between well-trained subjects and controls [9]. It seems that acute alterations which take place during exercise are possibly part of the body’s adaptations mechanism while increases in the level of reactive species or oxidant biomarkers following a more extended period of training may suggest the need for remedies in training plans and nutrition [5].

Well-structured training programmes, which are characterised by a distinct sequence of exercises, interrupt the redox equilibrium, provoking adaptations so that the body can deal with equal loads of RONS in the ensuing practices [10]. Accordingly, our insight of exercise-induced oxidative stress could likewise be relevant for exercise prescription. Hence, when coaches and sports experts aim to enhance the athletes’ performance and recovery processes, variables associated with oxidative stress should be taken into their consideration in order to optimise training load patterns and nutritional interventions, to maximise adaptations and as a result performance, especially in endurance events.

Training activities involving endurance, sprint, or resistance training are likely to induce metabolic stress as well as patterns of muscle damage. Furthermore, exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD) is linked with oxidative stress through the activity of neutrophils and macrophages [8, 11]. After an injury or muscle impairment, these specific leukocyte subsets infiltrate a damaged tissue for healing by releasing reactive and nitrogen oxygen species (RONS) and by synthesising pro-inflammatory cytokines. During this action, neutrophils can further increase oxidative stress through the “respiratory burst” [8] while nitric oxide (NO) can provoke highly reactive species [8, 10]. Besides, cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1b, and IL-1 receptor antagonists (ra) play a fundamental role in the regulation of inflammation as they contribute to the clearing of antigens and the restoration of tissue [12].

Training can have positive or negative effects on oxidative stress and inflammation variables depending on the training load, the exercises prescribed, the specificity, the athlete’s age, and their training experience [13]. Although distinct types of exercise may provoke different levels of oxidative stress in a specific pattern and lead to inflammatory responses in adolescent athletes, aggregated data related to those responses are elusive. This limitation occurs because different biomarkers, types of specimen, methodologies, sampling times, and testing protocols have been implemented to monitor the induced alterations [5]. Routinely in sports populations, redox homeostasis variations are determined by analysing several biomarkers, mainly in the blood by means of venepuncture sample collections. Such biomarkers can denote a specific type of harm on lipids, proteins, and DNA or the accumulation of certain antioxidants and reactive species. Still, for any distinct impairment that can be caused by a direct attack of reactive species during oxidative stress, varied biomarkers can be used. For example, for the monitoring of lipid peroxidation, several biomarkers (i.e. malondialdehyde (MDA), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs), conjugated dienes, F2-isoprostanes) can be utilised [13, 14]. However, all battery of assays representing a type of damage, including lipid peroxidation, have limitations as a wide range of products are formed in variable amounts, so attention is needed for the choice of the appropriate biomarker and the interpretation of results [2].

With more young athletes engaged in supervised training sessions, it is essential to define the most relevant variables to quantify their training adaptations and responses to different exercise regimes. Thus, this work aimed to (1) systematically search data reporting variations in variables related to redox and inflammation status in adolescent athletes, following short- or prolonged training periods in order for individuals that have an interest in the field gain a better understanding linked to each variable, and (2) examine the effect size of acute and chronic responses to training and identify the most sensitive variables to display those changes.

Methods

The present systematic review (SR) and meta-analysis (MA) was registered with the PROSPERO database of reviews (registration number: CRD42020152105) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines [15]. The PRISMA checklist is presented in Additional file 1: Appendix 1, indicating the page numbers where items of information are present in the current manuscript. Also, 20 authors whose papers included in MA (resulting in 27 articles) were contacted by email, of which ten replied and were able to provide data. Seven other articles included full data, and for three studies, results were estimated by using the above-mentioned software.

Screening—Eligibility

The inclusion criteria were based on the Cochrane guidelines for conducting systematic reviews [16]. The criteria for inclusion and exclusion were set and agreed by all three authors. Following the initial selection process of studies, three authors (EV, SP, and DT) independently completed the eligibility assessment in a blinded standardised way by screening the titles and abstracts. To be considered eligible, the manuscript had to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Language—published in English in a peer-reviewed journal.

-

2.

Population—healthy adolescent participants with a mean age ranging from 12 to 18 years of age.

-

3.

Training period—short-term training (i.e. a single training session or performance testing session) or long-term training periods (i.e. a more extensive period of training involving a micro-, meso-, and macro-cycle ranging from 45 days to 1 year).

-

4.

Biomarkers—biomarkers associated with redox status and inflammation measured in blood (see the “Study Selection—Key Redox Status and Inflammation Mediator Variables” section).

-

5.

Design—non-randomized control trials (NRCTs) and case-control study designs.

Literature Search Strategy and Information Sources

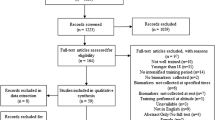

A computerised English-language literature search of electronic databases: PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, and ScienceDirect was conducted (December 2019). A search for relevant content related to fluctuations in biomarkers associated to oxidative stress and inflammation mediators in young athletic populations using the following search syntax was performed: (“oxidative stress” OR “oxidative damage” OR “redox alterations” OR “redox status”) AND (“adolescent athletes” OR “young athletes”) AND (“post-training” OR “post-exercise”) or (“proinflammatory cytokines” OR “inflammation” OR “IL-6” OR “IL-1ra”) AND (“adolescent athletes” OR “young athletes”) AND (“post-training” OR “post-exercise”). The initial search was conducted by one author (EV). The search syntax was combined with Boolean operators, and the quotation marks were used for phrase searching (i.e. combinations of two or more words). The search was limited to papers published in the English language, which included the monitoring of the studied parameters following a short- or a long-term period of training. In addition, the reference lists of articles retrieved were screened manually for additional relevant papers, as part of the secondary search to uncover any additional articles that met the inclusion criteria. Two authors (SP and DT) independently carried out the searches for study selection to minimise potential selection bias. Disagreements were discussed between three authors (EV, SP, and DT) and resolved by consensus. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart showing the flow of papers through the study selection process.

Study Selection—Key Redox Status and Inflammation Mediator Variables

The current systematic review focused on exploring (i) endogenous antioxidant variables: superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and catalase (CAT); (ii) oxidative stress markers: thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), malondialdehyde (MDA), reduced glutathione (GSH), protein carbonyls (PC), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC); and (iii) inflammatory mediators: interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-10 (IL-10). In instances where the title and abstract did not contain enough detail to indicate whether an article was relevant to the review, the complete article was obtained and read. This decision enabled the authors to determine whether the paper met the primary inclusion criteria. In instances where the primary purpose of the article was not an investigation exploring alterations in biomarkers associated with oxidative stress and inflammation due to applied training programs, the papers were excluded from the review. Specifically, studies involving supplementation interventions, exercise protocols in hypoxia or heat, and specific medical conditions (e.g. asthma) were excluded a priori, as they could have affected outcomes in those studies. Letters to the editor and conference abstracts were also excluded as these studies were not found to be methodologically quality assessable and/or critically appraisable.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by one author (EV) independently and a data check performed by a second author (SP), finding a 100% data check agreement. The following data were extracted from the included studies: (1) the study authors and date, (2) the number of participants and their characteristics (e.g. sample size, sex, sport, athletes’ features), (3) the explored redox status and inflammation variables, (4) the sampling time and description of activity/performance test used (e.g. training phase, pre- vs post-exercise, time of sampling), and (5) effects of applied testing protocols or training modalities on examined biomarkers.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Methodological quality assessment was conducted on each included article using a modified Downs and Black scale [17], which is appropriate for non-randomized control trials (NRCTs) and case-control study designs [18]. The Methodological Quality Checklist for each study includes twenty-seven items. For this review, twenty-six questions were scored totalling up to 27 possible points, as has previously been done [18]. The questions were categorised under 4 sections: reporting (10 items; items 1–10), external validity (3 items; items 11–13), internal validity—study bias (7 items; items 14–20), and internal validity—confounding selection bias (6 items; items 21–26). The quality assessment of the articles was conducted by two reviewers (SP and EV). The observed differences were resolved by a third reviewer (DT), and details for overall study scores are provided in Additional file 1: Appendix 2.

Statistical Analysis

Assessment of Effect Size

Statistical analyses were performed using “The Comprehensive Meta-analysis software” (version 3.0, Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). In cases of missing data, authors were contacted via email and asked to provide the necessary information. If no response was received, possible means and SDs were estimated from figures using computer software (ImageJ, Bethesda, MD, USA; Imagej.net). All analyses were conducted using a random-effects model to account for measurement variability and heterogeneity among the studies. For the completion of meta-analysis for each examined variable, a minimum of five studies was agreed. Further, the effect size (ES) was calculated according to Hedges’ g [19], which is similar to Cohen’s d, but it includes an adjustment for small sample size. The magnitude of the effects sizes was interpreted as changes using the following criteria: trivial (< 0.20), small (0.21–0.60), moderate (0.61–1.20), large (1.21–2.00), very large (2.01–4.00), and extremely large (> 4.00) [20]. The mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the included studies.

Assessment of Heterogeneity

The chi-square Cochran’s Q test (χ2) is meant to test the null hypothesis that there is no dispersion across effect sizes. As we wish also to quantify this dispersion, the measure of I-squared (I2) and tau-squared (t2) were implemented. Therefore, the I2 statistic was used for the evaluation of statistical heterogeneity among studies while values of 25, 50, and 75% represent low, moderate, and high statistical heterogeneity, respectively [21]. Furthermore, the tau-squared (t2) estimates the “between studies” variance [13, 21].

Publication Bias

The publication bias was assessed by examining the asymmetry of the funnel plots using Egger’s test, and significant publication bias was considered when p > 0.10 [22]. Whether publication bias was recorded, then, Duval and Tweedie’s “Trim and Fill” method was further considered which not only indicates the significance of publication bias but also provides bias-adjusted results [23].

Results

Literature Search Results

The literature search ended in September 2019, and the primary database search revealed 346 potentially relevant journal articles. Figure 1 presents the number of articles found in each electronic database and a detailed PRISMA flow chart of the literature search, including all the steps performed. Once duplicates and non-relevant papers were removed, 123 titles and abstracts remained in the reference manager (EndNote V.X.8). Following the examination of titles, abstracts, and keywords of all these manuscripts, 81 academic studies were deemed eligible and retained for full-text analysis. After additional full-text analysis, 36 studies were deemed eligible and included in the systematic review. A total of 27 studies were used to conduct the meta-analysis. Concerning the meta-analyses related to redox homeostasis variables, studies with male adolescents and with results collected immediately post-training or performance testing that could be converted in similar units were considered. The reason for focusing on male adolescents is that many physical and physiological changes occur between 12 and 14 years of age, especially in girls, which could have an impact on the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis. From the included studies, 5 have a mean age for young athletes below 14 years [16, 24,25,26,27]. Moreover, twenty-two out of the 27 included studies are characterised as uncontrolled trials (UCTs) [9, 16, 24, 25, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] and five studies as control trials (CTs) [26, 27, 46,47,48].

Data Extraction

A summary of the studies included in the systematic review is presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3. In total, 856 adolescents including 569 males, 174 females, and 113 male controls were included ranging from various sports (e.g. athletics, basketball, cross-country, handball, judo, multi-sport, rowing, soccer, swimming, volleyball, water polo, tennis, and wrestling). Table 1 displays the twenty-one studies where the effect of a short-term training period, event, or performance testing on redox status variables was examined. In Table 2, the 8 studies with an extended period of training are shown, of which 3 studies include short and long protocols [26, 45, 53]. In Table 3, the ten studies which discussed results relevant to cytokines are presented. For the redox status meta-analyses, a total of 459 young male athletes were included from 9 different sports (athletics, basketball, handball, multi-sport, rowing, soccer, swimming, volleyball, and wrestling).

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality scores of the included studies ranged from 16 to 23. Twelve of the included studies [26,27,28,29, 37,38,39, 41, 46,47,48, 55] were of strong quality (rating above 75%), while the rest of the investigations were deemed moderate (rating 50 to 75%) (Additional file 1: Appendix 2).

Meta-analysis Findings

In total, ten meta-analyses were conducted, and the significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all analyses. Seven out of the 10 performed meta-analyses showed a significant effect size. In particular, the random pooled ES of eight studies included in the meta-analysis showed a large acute increase of TBARS levels (ES 1.317; 95% CI 0.522 to 2.112; Z = 3.247, p = 0.001) after performing a maximal test by young athletes in several sports (Fig. 2a). The high heterogeneity (χ2 = 83.3, p = 0.000, I2 = 91.59, t2 = 1.153) illustrates that 91.59% of the variance reflects differences in the true ES while the other percentage reflects sampling error. On the contrary, the estimated random pooled ES for chronic response of TBARS is small and the statistical heterogeneity low (ES 0.568; 95% CI − 0.061 to 1.197; Z = 1.768, p = 0.077; χ2 = 25.7, p = 0.000, I2 = 80.59, t2 = 0.487) (Fig. 2b). As publication bias was recorded for chronic TBARS responses, the Duval and Tweedie’s “Trim and Fill” method was applied. Consequently, one study trimmed, and the new ES was even lower but still small (i.e. ES 0.334; 95% CI − 0.334 to 1.003).

The random pooled ES of eight studies showed a large decrease of GSH level (ES − 1.701; 95% CI − 2.698 to − 0.705; Z = − 3.347, p = 0.001) immediately after a short duration of training but a moderate increase following an extended period of training in young athletes (ES 1.131; 95% CI 0.350 to 1.913; Z = 2.839, p = 0.005) (Fig. 3a, b). The statistical heterogeneity was high for both GSH conditions (χ2 = 83.8, p = 0.000, I2 = 91.65, t2 = 1.757) and (χ2 = 41.8, p = 0.000, I2 = 88.05, t2 = 0.836), respectively. As publication bias was also recorded for chronic GSH responses, the “Trim and Fill” method was applied. However, the ES did not change.

Regarding protein carbonyls (PC), an extremely large increase (ES 4.164; 95% CI 1.716 to 6.613; Z = 3.333, p = 0.001) was observed following an acute period of training (Fig. 4a) with the heterogeneity to be high (χ2 = 151.9, p = 0.000, I2 = 96.70, t2 = 8.718). From endogenous enzymes, the random pooled ES of seven studies showed a small increase of SOD level (Fig. 4b) following chronic training (ES 0.513; 95% CI 0.062 to 0.963; Z = 2.230, p = 0.026). The statistical heterogeneity was high as well (χ2 = 10.5, p = 0.033, I2 = 61.9, t2 = 0.163). Despite the recorded publication bias in chronic SOD concentrations, the imputed point estimate did not change after using Trim and Fill adjustment.

Further, the random pooled ES of six studies showed a moderate acute increase of TAC level (ES 1.057; 95% CI − 0.044 to 2.158; Z = 1.882, p = 0.060) and a trivial ES (Fig. 5a, b), after a longer period (ES − 0.055; 95% CI − 0.404 to 0.293; Z = − 0.310, p = 0.756). The statistical heterogeneity was high for both conditions (χ2 = 54.2, p = 0.001, I2 = 91.13, t2 = 1.390) and (χ2 = 10.2, p = 0.068, I2 = 51.24, t2 = 1.252), respectively. In relation to cytokines (Fig. 6a, b), the random pooled ES of eight and six studies showed a very large and large increase in IL-6 and IL-1ra (ES 2.291; 95% CI 1.082 to 3.501; Z = 3.713, p = 0.000 and ES 1.599; 95% CI 0.347 to 2.851; Z = 2.503, p = 0.012) and high heterogeneity following acute exercise modality, correspondingly (χ2 = 78.2, p = 0.000, I2 = 91.04, t2 = 2.621 and χ2 = 45.8, p = 0.000, I2 = 91.27, t2 = 2.107).

For the examination of publication bias, Egger’s test [22] was performed for each group of studies to provide statistical evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (Table 4). The results indicated publication bias for changes in TBARS, GSH, and SOD after chronic exercise (i.e. p > 0.10). For these specific analyses, the “Trim and Fill” method was further performed to provide bias-adjusted results [23].

Discussion

Sports scientists and coaches are increasingly realising the value of redox homeostasis changes in athletes’ training adaptations. However, we have not yet been able to implement all these measurements efficiently and routinely within an applied sports science setting. There are many biomarkers, conditions, and protocols that make this implementation challenging for the majority of sports science “support” staff. Therefore, we aimed through this paper to use the following paragraphs (par. 4.1 to 4.6) to make it clearer to individuals that have an interest in the field and further understand results related to each variable. Additionally, we performed the meta-analysis to identify which markers are more sensitive and display significant variations and could, therefore, be useful to practitioners.

Based on the meta-analysis outcomes, significant alterations in oxidative stress and cytokines levels are noted after acute exercise, ranging from moderate to extremely large. In contrast, the variations after chronic exercise ranged from trivial to moderate (Table 5). However, we should be cautious with how those results are interpreted and whether supplementation can be provided, as recent studies suggest that some alterations may display the necessary signalling for performance adaptations [9, 39]. The results from the Downs and Black checklist of studies emphasised many areas in need of improvement to increase the quality of research in this field. Specifically, improvement is required mainly for internal validity—study bias, internal validity confounding—selection bias, and reporting of probability and important adverse outcomes. The high heterogeneity in specific meta-analysis advocates the need for further exploration and requiring consistency when we deal with the assessed variables. Many reasons can increase heterogeneity such as the study design, duration of follow-up of protocols, or the accuracy of results. Besides, the observed publication bias for specific variables (TBARS, GSH, and SOD) following long-term periods of training further supports those findings. In the next sections, analytical findings from a broad range of relevant studies in adolescent athletes are presented.

Lipid Peroxidation

Meta-analysis outcomes confirmed that the ES of observed modifications in TBARS following a short period of training or performance testing is indeed large (ES 1.317; 95% CI 0.522 to 2.112). After a short duration event, TBARS tend to increase, provoking lipid peroxidation in adolescent athletes significantly. As the heterogeneity was high, the “between studies” variance in ES was estimated at t2 = 1.153. However, the use of TBARS for the monitoring of long-term changes needs further investigation as the effect size was small (ES 0.568; 95% CI − 0.061 to 1.197) and publication bias (PB) was noted. Many reasons could have contributed to PB, such as the use of different duration protocols and the small samples in the included researches.

Acute Exercise

In most published investigations, greater levels of lipid peroxidation have been mentioned after a short period of exercise or shortly after a performance assessment. However, a few studies found no noticeable changes [18, 34, 42, 47,48,49], and a diminished level of lipid peroxidation was reported in two studies [45, 52]. Increased TBARS or MDA concentrations have been revealed in young soccer players after a sequence of repeated sprints or a Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test [30, 49], in long-distance runners after culmination of a maximal test [26, 46], in rowers following a maximal simulated test [35], in swimming after performing different sets (i.e. interval or continuous) [33, 43, 58], and in handball players following a graded exercise test (GXT) [9]. In contradiction, in research where endurance athletes run the distance of a half marathon (21 km) twice throughout a training period (i.e. at the beginning and after 1 year of training; e.g. pre- and post-assessment), TBARS decreased immediately post-run in both efforts [45]. Further, TBARS decreased after a continuous aerobic exercise session in basketball but not after a high-intensity training session of the same extent [52]. Nonetheless, these markers remained unaltered in five studies where young basketball, handball, or healthy athletes were incorporated [42, 47,48,49, 51, 53].

Chronic Exercise

Based on the impact of prolonged training period on lipid peroxidation, heightened levels of TBARS were detected in junior athletes after 6 months of soccer practice [27] and in swimmers after the culmination of 13 weeks but not after 23 weeks of preparation [25]. Likewise, young track and field athletes had greater levels of TBARS after the execution of a maximal run test after 6 and 11 months of training, respectively. Those high rates remained elevated up to 1 h after the completed trial [26]. However, TBARS and MDA decreased in endurance runners when a 21-km race was repeated after 1 year of training, both pre- and post-evaluation [45], after 45 days of soccer training [53], and after 12 weeks of endurance exercise in soccer [54]. No deviations were noted after 23 weeks of swimming training [16].

GSH Status

Based on the meta-analyses’ reports, the variations reported in swimming, rowing, handball, and athletics [9, 24, 35, 54] were considerable as they verified a large ES (ES − 1.701; 95% CI − 2.698 to − 0.705) suggesting the influence of those modalities on juvenile athletes. Also, the heterogeneity was high, and the “between studies” variance in ES was determined at t2 = 1.757. The effect size of those changes after a lengthier period was moderate and the publication bias significant.

Acute Exercise

The GSH level raised in 26 swimmers after interval or continuous swimming [33, 51]. In endurance runners, GSH levels only increased 4 h post-race, but no change was monitored at 2 h or 24 h post-test [44]. However, in a group of half-marathon runners, GSH decreased after a 21-km run during pre-season [45]. Similarly, GSH levels dropped in reply to a maximal test in trained adolescent handball players [9], after the completion of two distinctive swim tests (i.e. 100 m and 800 m) [32], after 12 sessions of 50 m intermittent swimming [24], and following a soccer practice [53]. Moreover, no variations were viewed in GSH levels in handball, where the competitors had to carry out a maximal test [47], and in rowing [35].

Chronic Exercise

An increased GSH level was detected in adolescent swimmers after 23 [16] or 13 weeks of exercising [25] and in junior soccer players during a 45-day training time [53]. A decreased GSH level was observed in an athletic population after a maximal test performed after 11 months of training [26] and after 6 months of regular soccer practice [27]. The overall ES of increment was moderate (ES 1.131; 95% CI 0.350 to 1.913). No shifts in GSH levels were discovered in athletics where long-distance runners completed a half-marathon run post-season [45]. However, long-term variations documented in swimming following short- or long-term periods of practice [25, 32] were more profound compared to other studies. It seems that athletes adapt to their antioxidant adaptations after longer periods of training.

Endogenous Enzymatic Antioxidants

Meta-analysis was implemented for variations in SOD accumulation after a prolonged period of training since a minimum of five investigations (i.e. consisting of results feasibly to convert in common units) could be collected only for this condition. The ES of alterations in SOD was small (ES 0.581; 95% CI − 0.259 to 1.420) following long-term periods of work out and the publication bias significant. Besides, the between studies variation was found at t2 = 0.163.

Acute Exercise

Following short-term exercise, the levels of SOD reduced in three studies. SOD decreased in handball, where a maximal test and an ordinary exercise session were included, and in athletics [9, 45]. However, no difference was demonstrated after a GXT [9] or a 21-km half marathon race at the start of the period [45]. No fluctuations in SOD concentrations were reported after a treadmill test in athletics [46], handball [9], or endurance runners [44]. Yet, SOD was higher following a run consisting of ten sets of 2 × 200 m sprints in soccer players [30]. GPx was similarly high after a treadmill assessment completed by an athletic population [46] and after the execution of two different swimming trials (100 and 800 m) in juveniles [32]. CAT levels increased in a group of elite Greek rowers [35], in a team of female basketball players after their continuous aerobic exercise [52], and in adolescent track and field athletes shortly after the exercise period in response to a GXT (at the onset of the season) and soon after the testing [26]. However, such enzymes remained unaffected after a 21-km run at pre-evaluation trial [45]. Only one investigation presented a reduction in CAT levels [9].

Chronic Exercise

Both enzymes, SOD and CAT, were elevated after 6 months of soccer training [27] and 16 weeks of swimming training [25]. Moreover, in the swimming study, GPx substantially reduced [25]. However, CAT rose after 1 year of exercise and completion of a 21-km half marathon run [9], and immediately after a maximum trial performed at the end of an 11-month training season [26]. Besides, it persisted unchanged after 23 weeks of preparation in swimming [16]. Besides, SOD and GPx were unaltered during the practice season in soccer [36] but dropped after 1 month of training in soccer and in a group of endurance athletes who completed a 21-km run after 1 year of training [45, 54].

Protein Modification

Likewise, only one meta-analysis was conducted for differences in PC concentration after a short period of training, since we could not gather more studies evaluating long-term modifications in juvenile athletes. The overall ES for alterations regarding PC were extremely large (ES 4.164; 95% CI 1.716 to 6.613) and the variance between the studies high (t2 = 8.718). Therefore, more consistency is recommended when the evaluation of PC is incorporated in studies.

Acute Exercise

PC increased after a sprint exercise in soccer, 2000 m maximal testing on a rowing ergometer [30, 35], and a short period of interval swimming [24]. They were also considerably above resting values immediately post and 1 h post-exercise in all athletics groups (athletes and controls) during pre-training testing [26]. However, carbonyls remained unaffected in two surveys in swimming [33, 43] and wrestling [50].

Chronic Exercise

PC rose noticeably after 16 weeks of swimming and after 11 months of athletic preparation [25, 26]. In the research mentioned above [26], PC levels remained substantially above resting values immediately post and 1 h post-exercise in both groups of young participants (trained adolescent and controls) at mid- and post-season screenings (except 1 h post- at mid-training) [26]. No meta-analysis was performed as the number of studies was limited.

TAC Capacity

Although no publication bias was detected for studies related to the measurement of TAC in both conditions (i.e. acute and chronic), the ES of changes were moderate after a short period (ES 1.057; 95% CI − 0.044 to 2.158) but trivial following more extended periods of training. Also, the variance between the studies was low (t2 = 0.096 and 0.119, respectively).

Acute Exercise

Most studies have shown a rise in the TAC of athletes at the end of discrete types of short-term exercise. Notably, an increase in TAC was noted following a series of sprint trials or a Wingate test in soccer [30, 31], a short interval swim of 12 × 50 m at an intensity between 70 and 75% [24], 2 sets of 4 × 50 m swimming [51], and a simulated rowing ergometer test [35]. Furthermore, TAC increased immediately at the end of the exercise in all groups in track and field (young athletes and controls) conducted at baseline testing [26]. In comparison, the antioxidant capacity declined in basketball after the completion of a circuit program [34], in handball after a maximal trial on the bike [9], and after a Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test in soccer players [49]. The total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) remained stable following a 21-km race, at the beginning and end of a practice period [8], and regular soccer training [53].

Chronic Exercise

Long-term exercise was not found to result in considerable variations in TAC in most studies. These considerations had been recorded in several sports, such as after 16 and 23 weeks of swimming training [16, 25] and after 1 month of soccer practice [53]. However, no significant discrepancies were present after a repeated 21-km run at the end of the training course [45]. In contrast, increments in TAC were listed immediately after and 1 h after a maximal experiment was performed at mid- and post-season in two groups (trained adolescents and controls) in athletics [26].

Inflammatory Mediators

Almost in all considered studies, IL-6 and IL-1ra levels significantly increased after the performance of a short duration of exercise with the ES being very large (ES 2.291; 95% CI 1.082 to 3.501) and large (ES 1.599; 95% CI 0.347 to 2.851), respectively. The between studies variance was high for both cytokines, i.e. (t2 = 2.621 and 2.107, respectively). More specifically, IL-6 was raised in basketball players during the competitive period compared to the preparatory period [55]. In volleyball players, this cytokine increased either after a standard practice or after 7 weeks of training [28, 29, 58]. Likewise, excessive IL-6 levels have been confirmed in other team sports such as water polo (after 90 min of formal training) and handball (after a course of different run drills) [37, 39]. Moreover, in the cross-country, female adolescent runners demonstrated high IL-6 levels following typical endurance training [41]. The results observed in wrestling were similar either after one wrestling training session or following half of a school’s training period [38, 40].

In all the examined studies related to volleyball, IL-1ra was unaltered [28, 29, 58]. Unaffected IL-1ra concentration was also observed in handball after the performance of a series of 250 m run sprints [37]. Considering long-term wrestling training, IL-1ra also increased at the mid-year screening during a school year [40]. The long-term exercise enhanced the TNF-α level in basketball players during competition [55], in wrestling after 90 min of exercise [38], and in tennis immediately after the tournament [57]. Nonetheless, no marked variations in TNF-α were noted when wrestling practice was implemented for one training season [40] or in female water polo players after the culmination of 90 min of training [39]. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was measured in three surveys. IL-10 level was reduced in competitive basketball season [55] and reached its peak after 3 and 14 days of tennis camp [26] but continued to be stable after regular training in handball, which consisted of a set of 4 × 250 m runs on a treadmill [37]. Meta-analysis was performed for IL-6 and IL-1ra. It was found that the ES of shifts in IL-6 and IL-1ra were very large following various training modalities such as volleyball, wrestling, water polo, cross-country, and handball.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

Throughout our investigation about how specific modalities and periods of exercise can affect the redox and inflammation status of youth athletes, several issues were identified. The most remarkable was the use of various biomarkers to define the same type of oxidative stress damage or body’s antioxidant capacity, which mostly represent differing end-products. Additionally, the use of diverse analytic methods, applied testing protocols, and the expression of results in different units was among the limitations. Therefore, by employing precise criteria, we aimed to carry out the current meta-analyses and generalise results about variations on redox and inflammation status of young athletes.

Conclusions

The results of the present review demonstrated that both short- and long-term exercise are evident stressors of the athletes’ redox status leading to acute and chronic responses, respectively. Alterations in redox homeostasis biomarkers following acute exercise are more significant, while the variations after chronic exercise ranged from trivial to moderate. However, we should be cautious with how those results are interpreted. Of the inflammatory mediators, IL-6 and IL-1ra were the most sensitive cytokines to training paradigms in young athletes, whereas other cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-10’s sensitivity depended on the type of sport. In addition, the publication bias and high heterogeneity in specific meta-analyses advocate the need for further exploration and consistency when dealing with the assessed variables.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- RONS:

-

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- GPx:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- TBARS:

-

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- LOOH:

-

Lipid hydroperoxides

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione

- PC:

-

Protein carbonyls

- TAC:

-

Total antioxidant capacity

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IL-1ra:

-

Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

- TNF-α:

-

Tumour necrosis factor-α

- IL-10:

-

Interleukin-10

References

Azzi A, Davies KJ, Kelly F. Free radical biology - terminology and critical thinking. FEBS Lett. 2004;30:558(1-3):3-6.

Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 3rd ed: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Sies H, Jones DP. Oxidative stress. In Encyclopaedia of Stress (Fink G), 2nd Ed., Vol.3, Elsevier, Amsterdam. 2007;43-9.

Lewis NA, Howatson G, Morton K, Hill J, Pedlar CR. Alterations in redox homeostasis in the elite endurance athlete. Sports Med. 2015;45(3):379–409.

Nikolaidis MG, Kyparos A, Dipla K, Zafeiridis A, Sambanis M, Grivas GV, Paschalis V, Theodorou AA, Papadopoulos S, Spanou C, Vrabas IS. Exercise as a model to study redox homeostasis in blood: the effect of protocol and sampling point. Biomarkers. 2012;17(1):28–35.

Margaritelis NV, Theodorou AA, Paschalis V, Veskoukis AS, Dipla K, Zafeiridis A, Panayiotou G, Vrabas IS, Kyparos A, Nikolaidis MG. Adaptations to endurance training depend on exercise-induced oxidative stress: exploiting redox interindividual variability. Acta Physiol (Oxford). 2018;222(2):1–15.

Steinbacher P, Eckl P. Impact of oxidative stress on exercising skeletal muscle. Biomolecules. 2015;10;5(2):356-377. pmid:25866921.

Tiidus PM. Radical species in inflammation and overtraining. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;76(5):533–8.

Djordjevic DZ, Cubrilo V, Zivkovic, Barudzic N, Vuletic M, Jakovljevic V. Pre-exercise superoxide dismutase activity affects the pro/antioxidant response to acute exercise. Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2010;11(4):135–9.

Slattery K, Bentley D, Coutts AJ. The role of oxidative, inflammatory and neuroendocrinological systems during exercise stress in athletes: implications of antioxidant supplementation on physiological adaptation during intensified physical training. Sports Med. 2015;45(4):453–71.

Radak Z, Chung HY, Koltai E, Taylor AW, Goto S. Exercise, oxidative stress and hormesis. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7(1):34–42.

Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Asp S, Schjerling P, Pedersen BK. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. J Physiol. 1999;515:287–91.

He F, Li J, Liu Z, Chuang CC, Yang W, Zuo L. Redox mechanism of reactive oxygen species in exercise. Front Physiol. 2016;7(486):1–10.

Finaud J, Lac G, Filaire E. Oxidative stress: relationship with exercise and training. Sports Med. 2006;36(4):327–58.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Kabasakalis A, Kalitsis K, Nikolaidis MG, Tsalis G, Kouretas D, Loupos D, Mougios V. Redox, iron, and nutritional status of children during swimming training. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(6):691–6.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84.

Slimani M, Paravlic AH, Chaabene H, Davis P, Chamari K, Cheour F. Hormonal responses to striking combat sports competition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Sport. 2018;35(2):121–36.

Hedges L. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6:107–28.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Borenstein M, Higgins JP, Hedges LV, Rothstein HR. Basics of meta-analysis: I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1230 Epub 2017 Jan 6.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63.

Nikolaidis MG, Kyparos A, Hadziioannou M, Panou N, Samaras L, Jamurtas AZ, Kouretas D. Acute exercise markedly increases blood oxidative stress in boys and girls. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32(2):197–205.

Sahin SK. Increase oxidative stress inflammatory response in juvenile swimmers after a 16-week swimming training. European Journal of Experimental Biology. 2013;3(3):211–7.

Zalavras A, Fatouros IG, Deli CK, Draganidis D, Theodorou AA, Soulas D, Koutsioras Y, Koutedakis Y, Jamurtas AZ. Age-related responses in circulating markers of redox status in healthy adolescents and adults during the course of a training macrocycle. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2015;283921.

Zivkovic V, Lazarevic P, Djuric D, Cubrilo D, Macura M, Vuletic M, Barudzic N, Nesic M, Jakovljevic V. Alteration in basal redox state of young male soccer players after a six-month training programme. Acta Physiol Hung. 2013;100(1):64–76.

Eliakim A, Portal S, Zadik Z, Rabinowitz J, Rabinowitz J, Portal DA, Cooper DM, Zaldivar F, Nemet D. The effect of a volleyball practice on anabolic hormones and inflammatory markers in elite male and female adolescent players. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23(5):1552-5.

Eliakim A, Portal S, Zadik Z, Meckel Y, Nemet D. Training reduces catabolic and inflammatory response to a single practice in female volleyball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(11):3110–5.

Escobar M, Oliveira MWS, Behr GA, Zanotto-Filho A, Ilha L, Cunha GDS, Oliveira ARD, Moreira JCF. Oxidative stress in young football (soccer) players in intermittent high intensity exercise protocol. JEP online. 2009;12(5):1–10.

Hammouda O, Chtourou H, Chaouachi A, Chahed H, Ferchichi S, Kallel C, Chamari K, Souissi N. Effect of short-term maximal exercise on biochemical markers of muscle damage, total antioxidant status, and homocysteine levels in football players. Asian J Sports Med. 2012;3:239–46.

Inal M, Aky F, Turgut A, Mills GW. Effect of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism on free radical generation swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(4):564–7.

Kabasakalis A, Tsalis G, Zafrana E, Loupos D, Mougios V. Effects of endurance and high-intensity swimming exercise on the redox status of adolescent male and female swimmers. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(8):747–56.

Kurkcu R, Cakmak A, Zeyrek D, Atas A, Karacabey K, Yamaner F. Evaluation of oxidative status in short-term exercises of adolescent athletes. Biol Sport. 2010;27:177–80.

Kyparos A, Vrabas IS, Nikolaidis MG, Riganas CS, Kouretas D. Increased oxidative stress blood markers in well-trained rowers following two thousand-meter rowing ergometer race. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(5):1418–26.

LeMoal E, Groussard C, Paillard T, Chaory K, Le Bris R, Plantet K, Pincemail J, Zouhal H. Redox status of professional soccer players is influenced by training load throughout a season. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37:680–6.

Meckel Y, Eliakim A, Seraev M, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Sagiv M, Nemet D. The effect of a brief sprint interval exercise on growth factors and inflammatory mediators. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):225–30.

Nemet D, Oh Y, Kim HS, Hill M, Cooper DM. Effect of intense exercise on inflammatory cytokines and growth mediators in adolescent boys. Pediatrics Village. 2002;110:681–9.

Nemet D, Rose-Gottron CM, Mills PJ, Cooper DM. Effect of water polo practice on cytokines, growth mediators, and leukocytes in girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(2):356–63.

Nemet D, Pontello AM, Rose-Gottron C, Cooper DM. Cytokines and growth factors during and after a wrestling season in adolescent boys. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(5):794–800.

Nemet D, Eliakim A, Mills PJ, Meckal Y, Cooper DM. Immunological and growth mediator response to cross-country training in adolescent females. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:995–1007.

Otocka-Kmiecik A, Lewandowski M, Stolarek R, Szkudlarek U, Nowak D, Orlowska-Majdak M. Effect of single bout of maximal exercise on plasma antioxidant status and paraoxonase activity in young sportsmen. Redox Rep. 2010;15(6):275–81.

Tauler P, Ferrer MD, Romaguera D, Sureda A, Aguilo A, Tur J, Pons A. Antioxidant response and oxidative damage induced by a swimming session: influence of gender. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(12):1303–11.

Tian Y, Nie J, Tong TK, Baker JS, Thomas NE, Shi Q. Serum oxidant and antioxidant status during early and late recovery periods following an all-out 21-km run in trained adolescent runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110:971–6.

Tong TK, Kong Z, Lin H, Lippi G, Zhang H, Nie J. Serum oxidant and antioxidant status following an all-out 21-km run in adolescent runners undergoing professional training- a one year prospective trial. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(7):15167–78.

Dane S, Taysi S, Gul M, Akcay F, Gunal A. Acute exercise induced oxidative stress is prevented in erythrocytes of male long-distance athletes. Biology of Sport. 2008;25(2):115–24.

Djordjevic DZ, Cubrilo DG, Barudzic NS, Vuletic MS, Zivkovic VI, Nesic M, Radovanovic D, Djuric DM, Jakovljevic V. Comparison of blood pro/antioxidant levels before and after acute exercise in athletes and non-athletes. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2012;31:211–9.

Otocka-Kmiecik A, Lewandowski, M, Szkudlarek U, Nowak D, Orlowska-Majdak M. Aerobic training modulates the effects of exercise-induced oxidative stress on PON1 activity: a preliminary study. Sci World J 2014; 2014: 230271. pmid:25379522.

da Costa CSC, Barbosa MA, Spineti J, Pedrosa CM, Pierucci APTR. Oxidative stress biomarkers response to exercise in Brazilian junior soccer players. Food Nutr Sci. 2011;2:407–13. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2011.25057.

Hamurcu Z, Saritas N, Baskol G, Akpinar N. Effect of wrestling exercise on oxidative DNA damage, nitric oxide level and paraoxonase activity in adolescent boys. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2010;22:60–8.

Kabasakalis A, Nikolaidis ST, Tsalis G, Christoulas K, Mougios V. Effects of sprint interval exercise dose and sex on circulating irisin and redox status markers in adolescent swimmers. J Sports Sci. 2019;37:827–32.

Maric B. The influences of continuous and interval aerobic training on the oxidative status of women basketball players. Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2018:1–1.

Sopic M, Bogavac-Stanojević N, Baralić I, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Đorđević B, Stefanović A, Jelić-Ivanović Z. Effects of short- and long-term physical activity on DNA stability and oxidative stress status in young soccer players. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2014;54(3):354–61.

Vujovic A, Spasojevic-Kalimanovska V, Bogavac-Stanojevic N, Kotur-Stevuljevic J, Sopic M, Stefanovic A, Baralic I, Djordjevic B, Jelic-Ivanovic Z, Spasic S. Lymphocyte Cu/ZnSOD and MnSOD gene expression responses to intensive endurance soccer training. Biotechnol & Biotechnol Eq. 2013;27(3):3843–7.

Brunelli DT, Rodrigues A, Lopes WA, Gaspari AF, Bonganha V, Montagner PC, Borin JP, Cavaglieri CR. Monitoring of immunological parameters in adolescent basketball athletes during and after a sports season. J Sports Sci. 2014;32(11):1050–9.

Jurimae J, Vaiksaar S, Purge P. Circulating inflammatory cytokine responses to endurance exercise in female rowers. Int J Sports Med. 2018;39(14):1041–8.

Ziemann E, Zembroń-Lacny A, Kasperska A, Antosiewicz J, Grzywacz T, Garsztka T, Laskowski R. Exercise training-induced changes in inflammatory mediators and heat shock proteins in young tennis players. J Sports Sci Med. 2013;12(2):282–9.

Nemet D, Portal S, Zadik Z, Pilz-Burstein R, Adler-Portal D, Meckel Y, Eliakim A. Training increases anabolic response and reduces inflammatory response to a single practice in elite male adolescent volleyball players. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(9–10):875–80.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Evdokia Varamenti performed the database search and identified relevant articles, extracted and analysed data, conducted meta-analyses using effect size, and is the primary author of the manuscript. Samuel Pullinger identified related articles, assessed articles for methodological quality, and contributed to the writing of the paper. David Tod assisted in conducting meta-analyses, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and provided guidance and feedback on the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

Evdokia Varamenti, David Tod, and Samuel Pullinger declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest with the content of this review.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Appendix 1. PRISMA Check list. Appendix 2. The results of the methodological quality assessment using a modified 26-item Downs and Black checklist for all studies in meta-analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Varamenti, E., Tod, D. & Pullinger, S.A. Redox Homeostasis and Inflammation Responses to Training in Adolescent Athletes: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med - Open 6, 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-00262-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-00262-x