Abstract

Vitreous hemorrhages are important clinical manifestations of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Non-cleared vitreous hemorrhages could lead to hemosiderosis bulbi and glaucoma. Here, we describe the case of a type 2 diabetic patient presenting anterior segment and vitreous hemorrhages that resolved three days after treatment with a single intravitreal injection of dobesilate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vitreous hemorrhages are an important clinical manifestation of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. A vitreous hemorrhage may spontaneously get re-absorbed over time in some cases. However, sometimes it requires a pars plana vitrectomy to remove the hemorrhage because otherwise it may lead to retinal tears, retinal detachment, hemosiderosis bulbi and glaucoma, causing a further reduction in vision [1, 2]. Here, we report the early efficacy of a single intravitreal dobesilate injection in reducing vitreous hemorrhages caused by proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Case presentation

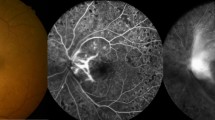

A 68-year-old Caucasian male with type 2 diabetes presented with one-month history of intense vision loss in his right eye. The patient did not seem had suffered any recent traumatic eye accident in the affected eye. The ophthalmic microscopic examination showed a pseudophakic right eye with both non-recent and recent hemorrhages in the anterior segment (Fig. 1a). A fundoscopic study revealed a massive vitreous hemorrhage (Fig. 1c). The intraocular pressure was 50 mmHg, which reduced to 14 mmHg after a paracentesis procedure.

Efficacy of an intravitreal dobesilate injection to clear a vitreous hemorrhage in a diabetic patient. Photographs A and C were taken at presentation, and B and D were taken after 3 days of treatment. The non-recent and recent hemorrhages viewed at the presentation in the anterior segment (a) resolved after the treatment (b). At the presentation (c) the fundoscopy showed a blurred view of the retina caused by bleeding at the vitreous. After treatment (d), a clear view to the retina with residual blood was depicted. Note in B the abnormal appearance of the pupil due to luxation of the lens. The arrow indicates the paracentesis site

Treatment

After approval by the Institutional Review Board, the patient signed an informed consent form, which included a comprehensive description of the off-label use of dobesilate and the proposed procedure. The patient received an intravitreal solution of dobesilate (150 μl) under sterile conditions in his right eye according to the international guidelines for intravitreal injections [3]. Prophylactic topical antibiotics were given for 2 days postinjection. Dobesilate was administered as a 12.5 % solution of diethylammonium 2.5-dihydroxybencenesulfonate (etamsylate, Dicynone® Sanofi-Aventis. Paris. France). No ocular side effects were observed upon the administration of dobesilate or during the following days. Three days after the treatment, the hemorrhage in the anterior segment (Fig. 1b) had completely cleared. An obvious improvement was also appreciated in that of the vitreous cavity (Fig. 1d). Vision improvement was also observed. While the vision of the right eye was completely lost before the treatment was administered, the visual acuity determined by the Snellen chart became 0.4 three days after the treatment. The intraocular pressure remained normal.

Discussion

A vitreous hemorrhage is a common disease that accompanies a wide variety of ophthalmological pathologies. The most common causes include proliferative diabetic retinopathy, vitreous detachment with or without retinal breaks, and trauma. Less common causes include vascular occlusive disease, retinal arterial aneurysms, hemoglobinopathies, neovascular age-related macular degeneration, and intraocular tumors. Hemorrhage into the vitreous gel results in rapid clot formation and is followed by a slow clearance of approximately 1 % per day [3]. The complications of persistant vitreous hemorrhages are hemosiderosis bulbi and glaucoma. The treatment option for non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage is a pars plana vitrectomy.

Dobesilate has been used for many years for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Its mechanism of action has not been established, but several possibilities have been proposed, including anti-inflammatory effects and inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [4, 5]. Although we cannot rule out the participation of these mechanisms, dobesilate clinical benefits for treatment of vitreous hemorrhage, probably should be largely attributed to its ability to inhibit the activity of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) that has been recently demonstrated [6]. FGF was the first inductor of vasculogenesis, proliferation of endothelial cells, and vascular permeability that was described [7]. Later, it was shown to be a broad-spectrum mitogen [8]. Recent data show that it should be better considered an inflammation-triggering and inflammation-sustaining protein, the mitogenic and permeability-inducing activities being manifestations of its inflammatory activity [9, 10]. The substantial increase in the permeability of the newly generated vessels has been attributed to FGF, which accumulates at high levels during diabetic retinopathy. In the case of hemorrhages, extravasated blood cells, such as monocyte-derived macrophages, also synthesize FGF [11]. FGF can also induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and phospholipase A2, as well as the ensuing production of prostaglandins in endothelial cells, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that favors chronic bleeding and inflammation in a vicious cycle [12–16]. It has been reported that high levels of FGF induce structural changes in intestinal vessels, resulting in the development of lethal intestinal hemorrhages [17], and in FGF-induced corneal neovascularization, resulting in hyphemas [18]. We have previously shown that neovascular growth with its subsequent bleeding can be suppressed by inhibiting FGF [19]. Forty-four years ago, orally administered dobesilate was used to treat vitreous hemorrhage in diabetic patients with unclear efficacy [20]. This is likely due to the route of administration that does not allow dobesilate to reach adequate concentrations in the eye, as previously discussed [21]. Furthermore, we have recently reported that an intravitreal injection of dobesilate displayed clinical efficacy in a patient with a submacular hemorrhage secondary to age-related macular degeneration [22]. Here, we describe the dramatic clearance of a vitreous hemorrhage in a diabetic patient after a single intravitreal injection of dobesilate, which is a representative case of five patients who show similar therapeutic outcomes. Our study seems to be in full agreement with the use of etamsylate for the treatment of periventricular hemorrhages in infants with very low birth weight. Prophylactic treatment has also been shown to reduce intraventricular bleeding in babies of less than 34-weeks of gestation [23].

The data shown in this report seems support that direct application of dobesilate (a drug with a long history of clinical safety that was recently re-discovered as an FGF inhibitor) could serve as a promising new clinical application to temper the most important pathological effects of vitreous hemorrhages in proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Conclusion

An intravitreal injection of dobesilate for the treatment of vitreous hemorrhages related to proliferative diabetic retinopathy is associated with prompt morphologic and visual improvement and may offer benefits over the natural course of the disease.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and images was obtained from the patient.

Abbreviations

- FGF:

-

Fibroblast growth factor

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase-2

References

Goff MJ, McDonald HR, Johnson RN, Ai E, Jumper JM, Fu AD. Causes and treatment of vitreous hemorrhage. Compr Ophthalmol Update. 2006;7:97–111.

Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Vitreous Hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;42:3–39.

Aiello LP, Brucker AJ, Chang S, Cunningham Jr ET, D’Amico DJ, Flynn Jr HW, et al. Evolving guidelines for intravitreous injections. Retina. 2004;24:S3–19.

Leal EC, Martins J, Voabil P, Liberal J, Chiavaroli C, Bauer J, et al. Calcium dobesilate inhibits the alterations in tight junction proteins and leukocyte adhesion to retinal endothelial cells induced by diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59:2637–45.

Lameynardie S, Chiavaroli C, Travo P, Garay RP, Parés-Herbuté N. Inhibition of choroidal angiogenesis by calcium dobesilate in normal Wistar and diabetic GK rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;510:149–56.

Fernández IS, Cuevas P, Angulo J, López-Navajas P, Canales-Mayordomo A, González-Corrochano R, et al. Gentisic acid, a compound associated with plant defense and a metabolite of aspirin, heads a new class of in vivo fibroblast growth factor inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11714–29.

Thomas KA, Rios-Candelore M, Giménez-Gallego G, DiSalvo J, Bennett C, Rodkey J, et al. Pure brain-derived acidic fibroblast growth factor is a potent angiogenic vascular endothelial cell mitogen with sequence homology to interleukin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:6409–13.

Thomas KA, Giménez-Gallego G. Fibroblast growth factors: broad spectrum mitogens with potent angiogenic activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1986;11:81–4.

Presta M, Andrés G, Leali D, Dell’Era P, Ronca R. Inflammatory cells and chemokines sustain FGF2-induced angiogenesis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2009;20:39–50.

Andrés G, Leali D, Mitola S, Coltrini D, Camozzi M, Corsini M, et al. A pro-inflammatory signature mediates FGF2-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2083–108.

Yum HY, Cho JY, Miller M, Broide DH. Allergen-induced coexpression of bFGF and TGF-β1 by macrophages in a mouse model of airway remodeling: bFGF induces macrophage TGF-β1 expression in vitro. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:12–22.

Fredj-Reygrobellet D, Baudouin C, Nègre F, Caruelle JP, Gastaud P, Lapalus P. Acidic FGF and other growth factors in preretinal membranes from patients with diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 1991;23:154–61.

Simó R, Carrasco E, García-Ramírez M, Hernández C. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2:71–98.

McDonnell K, Bowden ET, Cabal-Manzano R, Hoxter B, Riegel AT, Wellstein A. Vascular leakage in chick embryos after expression of a secreted binding protein for fibroblast growth factors. Lab Invest. 2005;85:747–55.

Ribatti D, Gualandris A, Belleri M, Massardi L, Nico B, Rusnati M, et al. Alterations of blood vessel development by endothelial cells overexpressing fibroblast growth factor-2. J Pathol. 1999;189:590–9.

Cha YI, DuBois RN. NSAIDs and cancer prevention: targets downstream of COX-2. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:239–52.

Jerebtsova M, Wong E, Przygodzki R, Tang P, Ray PE. A novel role of fibroblast growth factor-2 and pentosan polysulfate in the pathogenesis of intestinal bleeding in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H743–50.

Adini I, Ghosh K, Adini A, Chi ZL, Yoshimura T, Benny O, et al. Melanocyte-secreted fibromodulin promotes an angiogenic microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:425–36.

Cuevas P, Carceller F, Reimers D, Cuevas B, Lozano RM, Giménez-Gallego G. Inhibition of intra-tumoral angiogenesis and glioma growth by the fibroblast growth factor inhibitor 1,3,6-naphthalenetrisulfonate. Neurol Res. 1999;21:481–7.

Favre M. Treatment of diabetic retinopathy and recurrent hemorrhages into the vitreous with calcium dobesilate. Ophthalmologica. 1970;161:389–93.

Cuevas P, Outeiriño LA, Azanza C, Giménez-Gallego G. Intravitreal dobesilate in the treatment of choroidal neovascularization associated with age-related macular degeneration. Report of two cases. BMJ Case Rep. 2012; doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006619.

Cuevas P, Outeiriño LA, Azanza C, Angulo J, Giménez-Gallego G. Case report: resolution of submacular haemorrhage secondary to exudative age-related macular degeneration after a single intravitreal dobesilate injection. F1000 Res. 2013;2:271.

Hunt RW. Etamsylate for prevention of periventricular haemorrhage. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F3–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CP and GGG wrote the paper. OLA and AC were the physicians responsible for the patient in this case report. All authors participated in the concept, design/analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and they have given final approval for the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuevas, P., Outeiriño, L.A., Azanza, C. et al. Dramatic resolution of vitreous hemorrhage after an intravitreal injection of dobesilate. Military Med Res 2, 23 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-015-0050-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-015-0050-5