Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization recommends initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of delivery. Early initiation is beneficial for both mother and baby. Previous Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Surveys (ZDHS) have shown reduction in early initiation of breast feeding from 68% (2005/06) to 58% (2015). This study sought to investigate factors associated with early initiation of breast feeding among women aged 15–49 years in Zimbabwe.

Methodology

Secondary analysis of ZDHS 2015 data was done to investigate the association between early initiation of breast feeding and maternal, provider and neonatal factors using multivariate logistic regression (n = 2192).

Results

The majority of the study sample (78%) reported having practised early initiation of breastfeeding during their most recent delivery (preceding 24 months).Children who were put on skin to skin contact (AOR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.13–2.02) and those delivered by skilled attendants (AOR = 4.36, 95% CI 1.07–17.77) had greater odds of early initiation compared to those who were not. Other factors associated with early initiation were multiparity (AOR 1.82 95% CI 1.33–2.49) and rural residence (AOR 2.10 95% 1.12–3.93). However, having an abnormal birth weight, i.e. low birth weight (AOR 0.60 95% CI 0.36–0.99) and macrosomia (AOR = 0.42, CI 0.22–0.79) as well as delivery by caesarean section (AOR 0.1195% CI 0.06–0.19) were associated with reduced odds of early initiation.

Conclusion

Early initiation of breast feeding in Zimbabwe is mainly associated with residing in the rural areas and multiparity. The 78% rate of early initiation of breastfeeding was contrary to the 58% reported in the ZDHS findings. Interventions targeting an improvement in early initiation of breastfeeding must aim at women who deliver by caesarean section, women with babies of abnormal birth weight, primi-parous women and women residing in rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends initiation of breastfeeding within an hour of delivery [1]. This practice is termed ‘early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF). Early initiation is beneficial for both the mother and the baby. Benefits of this practice include exposing the newborn to colostrum, otherwise known as ‘first milk’, which is rich in protective factors [1, 2].EIBF has also been credited with facilitating bonding between mother and baby, stimulating breast milk production, reducing the incidence of post-partum haemorrhage and establishing successful and longer breastfeeding duration [3, 4]. Delaying initiation of breastfeeding is associated with a high risk of death within the first month of life [2, 5, 6].

According to UNICEF, Low to Middle Income Countries (LMICs) are disproportionately affected by suboptimal breastfeeding [7]. An analysis of DHS (Demographic Health Survey) data from 57 LMICs published in 2018 revealed that only 39% of children were breastfed within an hour of delivery (range by region of 31–60%) [8]. The 2010 Global burden of disease study revealed suboptimal breastfeeding practices to be within the top three leading contributors to disease in most countries in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) [9].

Factors which have been shown to be associated with EIBF include maternal education, residence, household income, maternal occupation, place of birth, cultural beliefs and the availability of health facility counselling services with marked variation of influence by region [10].

Literature suggests that policy makersprioritize exclusive breastfeeding without building as much emphasis on the uptake of EIBF [11]. It has also been advanced that there has been more focus on health facility based promotion for EIBF with little effort at strategiestargeting communities [11]. In line with its National Child Survival Strategy, Zimbabwe has adopted the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) as well as Infant & Young Child Feeding (IYCF) programmes aimed at promoting early initiation of breast feeding. If these initiatives are implementedproperly, they should cover health facility as well as community based interventions. However, review of serial Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Surveys (ZDHS) has revealed substantial reduction in EIBF from 68% (2005/06) to 58% (2015) [12].

Given this negative trend, it is important to explore the factors associated with uptake of the recommended practice of EIBF to inform and target programming efforts.This study sought to investigate the predictors of early initiation of breast feeding among women aged 15–49 years in Zimbabwe using ZDHS 2015 survey data. Specifically, the investigators set out to determine the maternal, newborn and provider factors associated with EIBF. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework that guided the setting up of the research questions and methodology.

Methods

Data

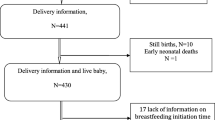

Data derived from the 2015 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (ZDHS) were used for secondary analysis in this study in order to determine the predictors of early initiation of breastfeeding among Zimbabwean women. The ZDHS was conducted by the Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency on a nationally representative sample of men and women in their reproductive age. The 2015 ZDHS samples were selected using a stratified two-stage cluster design with census enumeration areas as sampling units for the 1st stage and households for the 2nd stage. All women age 15–49 who were either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors who stayed in the households the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. The sample size for the number of women of reproductive age in the 2015 ZDHS dataset was 9955. In this study, further selection processes were conducted as illustrated in Fig. 2 according to the following eligibility criteria:

-

History of live birth over the preceding 24 month period

-

History of breastfeeding

-

Outcome variable data available for participant record

-

Consented to HIV testing for the survey

Following these exclusions, most of the original sample of 9955 was trimmed down to the final analysis sample of n = 2192. This was because 75% of the sample had given birth more than 24 months prior to data collection and we sought to avoid the influence of recall bias.

Measurement of outcome variable

The outcome variable of interest was ‘early breastfeeding initiation’, which was defined as, ‘initiation of breastfeeding within one hour after birth’.

Independent variables

The independent variables used in this study were derived from the conceptual framework (Fig. 1) depending on availability of the information in the ZDHS dataset. They were categorized into three groups: maternal, newborn and health care provider related factors.

Maternal factors included sociodemographic indicators such as Age in years (15–19, 20–34, 35+); Residence (Rural, Urban); Religion (None, Christian, Apostolic sect, Other); Wealth quintile (Lowest, Second, Middle, Fourth, Highest); Educational level (no formal education, primary, secondary or higher education); Employment status (currently employed, not currently employed); and Parity (1, 2–4, 5 & above). The health seeking behaviour variable, Number of ANC visits was also analysed. The variable HIV status was also included in the analysis (positive, negative).

The Newborn factor included in this analysis which was available in the ZDHS dataset was Birth Weight (low birth weight, normal weight, macrosomia).

Health care provider related factors were measured using the following variables: Place of delivery (public, private);Exposure to skilled provider at delivery (Yes, No);Exposure to skin-skin contact (Yes, No), andMode of delivery (Vaginal delivery, Caesarean section).

In addition, the analysis also controlled for determinants for maternal health seeking behavior whose data was available in the DHS dataset. This included exposure to various media modalities (radio, TV, newspapers and internet) and male partner’s education level (None, Primary, Secondary, Tertiary).

Statistical analysis

Analyses included descriptive data analyses for frequencies and proportions, chi2 testing for simple associations between selection of independent variables and outcome variable as well as modelling for simple and multivariate regression analyses. Prevalence and odds ratio at (95% CI: Confidence Intervals) were calculated using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Description of the study sample

A sample of 2192 women aged 15 to 49 underwent analysis in this study. The majority of the study sample (78%) reported having practised early initiation of breastfeeding during their most recent delivery (preceding 24 months) compared to 22% of the study population who did not practice EIBF. Table 1 shows the distribution of the study population by age, level of education and place of residence. The study sample was predominantly rural (67%), with a high literacy level (99%) which is fairly representative of these demographic features within the Zimbabwean population.

Logistic regression

The results of the adjusted OR, p-value and 95% CI for the independent variables that emerged significant following multiple logistic regression modelling are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

This study aimed at investigating the predictors of early initiation of breast feeding among women aged 15–49 years in Zimbabwe using secondary data from the ZDHS 2015 survey. The majority of the study sample (78%) reported having practised EIBF during their most recent delivery (preceding 24 months) and this EIBF rate was higher than original findings from the ZDHS 2015 survey. The sample used for this analysis was confined to the preceding 24 month period in order to cater for the possibility of recall bias. The discrepancy may be explained by the increased thrust from the Ministry of Health & Child Care on improving Quality of Care during the delivery process in more recent times thus improving the practice and uptake of early initiation of breastfeeding in the period under study compared to the whole DHS sample. The findings in this sample also show a higher EIBF rate than other studiesin Chipinge, Zimbabwe (52%) and, rural Tanzania (51%) and South East Asia (25%) [13,14,15].

Having health workers who are skilled before, during and after the baby is delivered is vital in ensuring successful EIBF and in our study, a number of health care provider related factors emerged as determinants for the practice of early initiation of breastfeeding.

Attendance by skilled health personnel at delivery was shown to be a strong predictor for achieving EIBF among Zimbabwean women. This aligns with literature from other settings where delivery through traditional birth attendants or other non-skilled cadres was associated with delayed breastfeeding initiation [8, 13]. A qualitative study carried out in Ghana also revealed the perception from communities that health facility delivery would facilitate EIBF because the staff encouraged the practice [11].This demonstrates that most skilled health providers were trained in both teaching and skill for successful EIBF and were effectively passing it on to the mothers. However, this factor had a wider 95% Confidence Interval range which lowered its statistical significance.

We found thatwomen who delivered by caesarean section were less likely to practice EIBF compared to those who had a vaginal delivery. A secondary analysis paper of the WHO Global survey published in 2017 also showedEIBF to be significantly lower among women with complications during pregnancy and caesarean section delivery [15]. Similar findings have also been reported in other settings [14,15,16]. Caesarean section birth has been found to be significantly associated with higher rates of pre-lacteal feeding which militates against EIBF [15, 17]. This finding can be attributed to lengthy postoperative care which delays mother-baby contact.

The convenient and natural intervention of skin to skin contact is vital to survival of the newborns yet it is still unpopular due to separation of the mother-baby pair for routine post-delivery procedures [18].This study revealed that women who reported having been subjected to skin to skin contact with their babies immediately post-delivery had higher odds of having practiced EIBF. This finding is in line with evidence which shows that immediate post-partum skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn facilitates EIBF and has other advantages [1, 18]. Early mother-baby contact soon after delivery enhances EIBF as well as improving the mother-baby relationship [19].

Birth weights outside of the normal ranges of 2500 to 4000 g were also found to be associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding in this study. Mothers who delivered low birth weight babies were also shown to be less likely to initiate breastfeeding early in other studies in similar settings [13].In most settings, abnormal weight babies tend to be separated from their mothers for longer periods post-delivery as they may suffer from other morbidities requiring intervention. However, this separation then also exacerbates the situation as the babies fail to access the advantages of EIBF.

Multiparity was also found to be significantly associated with increased rates of EIBF and this is consistent with previous studies in which mothers who had three or more children had nearly twice higher odds of EIBF within one hour of birth compared to first time mothers [10, 16]. We postulated that first pregnancies tend to have a higher incidence of delivery complications which may result in separation of the mother-baby pair. However, it may also be reflective of the lack of knowledge on the importance of EIBF and therefore low demand, which then improves with serial pregnancies.

Contrary to the findings by the Tanzanian DHS which showed that urban mothers have a higher uptake of EIBF than rural mothers (62 and 45% respectively) [20], we found out that mothers residing in rural areas were more likely to practise EIBF in the Zimbabwean setting.

The ZDHS data that was used for this analysis is nationally representative and results from application of strict standardised data collection protocols administered by trained study personnel using validated questionnaires, thus rendering a strong basis for generalization and translation of findings to inform policy and practice.

However some limitations arose because of the secondary nature of the methodology. For example because secondary data was used, information on other important factors highlighted in the literature review and the conceptual framework e.g. pre-lacteal feeding, could not be made available. The DHS data did not have comprehensive information on babies who were born at home and their weight was unknown. It was also not possible to establish causality due to the cross-sectional methodology employed in this population based survey.

Conclusions

Early initiation of breast feeding in Zimbabwe is mainly associated with residing in the rural areas and multiparity. Therefore, there is need to invest in programs to improve the practice among women living in urban settings and there is also need to strengthen support for nulliparous women on breastfeeding education during ANC, delivery and immediately post-partum e.g. pregnancy and lactation support groups. Additional focus must be given toearlier breastfeeding initiation for stable caesarean section and abnormal birth weight deliveries.

Abbreviations

- BFHI:

-

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative

- DHS:

-

Demographic & Health survey

- EIBF:

-

Early Initiation of Breastfeeding

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IYCF:

-

Infant & Young Child Feeding

- LMICs:

-

Low to Middle Income Countries

- SSA:

-

Sub Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ZDHS:

-

Zimbabwe Demographic & Health Survey

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2017. Available from: (http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/breastfeeding-facilities-maternity-newborn/en/). [cited 2018 Aug 14]

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

Brandtzaeg P. Mucosal immunity: integration between mother and the breast-fed infant. Vaccine. 2003;21(24):3382–8.

Goldman AS. Modulation of the gastrointestinal tract of infants by human milk. Interfaces and interactions. An evolutionary perspective. J Nutr. 2000;130(2S Suppl):426S–31S.

Debes AK, Kohli A, Walker N, Edmond K, Mullany LC. Time to initiation of breastfeeding and neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 Suppl 3:S19.

NEOVITA Study Group. Timing of initiation, patterns of breastfeeding, and infant survival: prospective analysis of pooled data from three randomised trials. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(4):e266–75.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The state of the world’s children 2016: A fair chance for every child. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2016.

Oakley L, Benova L, Macleod D, Lynch CA, Campbell OMR. Early breastfeeding practices: Descriptive analysis of recent Demographic and Health Surveys. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(2) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5900960/. [cited 2018 Aug 15].

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study, 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60.

Ekubay M, Berhe A, Yisma E. Initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth among mothers with infants younger than or equal to 6 months of age attending public health institutions in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13(1):4.

Tawiah-Agyemang C, Kirkwood BR, Edmond K, Bazzano A, Hill Z. Early initiation of breast-feeding in Ghana: barriers and facilitators. J Perinatol Off J Calif Perinat Assoc. 2008;28(Suppl 2):S46–52.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency and ICF International. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2015: Final Report. Rockville: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and ICF International; 2016.

Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, Karkee R, Binns CW. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding in Western Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9562–74.

Exavery A, Kanté AM, Hingora A, Phillips JF. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in rural Tanzania. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4582933/. [cited 2018 Aug 16].

Takahashi K, Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Vogel JP, Souza JP, Laopaiboon M, et al. Prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey. Sci Rep. 2017;7 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5359598/. [cited 2018 Aug 15].

Patil CL, Turab A, Ambikapathi R, Nesamvuni C, Chandyo RK, Bose A, et al. Early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding: results from the eight-country MAL-ED study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;34:10.

Patel A, Banerjee A, Kaletwad A. Factors associated with Prelacteal feeding and timely initiation of breastfeeding in hospital-delivered infants in India. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(4):572–8.

Moore ER, et al. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22592691. [cited 2018 Aug 15]

Nakao Y, Moji K, Honda S, Oishi K. Initiation of breastfeeding within 120 minutes after birth is associated with breastfeeding at four months among Japanese women: a self-administered questionnaire survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2008;3(1):1.

Tanzania - Demographic and Health Survey 2010 [Internet]. Available from: http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1510. [cited 2018 Aug 17]

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants from the 2015 ZDHS survey and the data collection team. In addition, we acknowledge Measure DHS for the permission to use the data for the study. We are also thankful for the technical support provided by the DHS Program and in particular the analytical support provided by Kerry MacQuarrie, Adrienne Cox, Ann Mwangi and Anthony Chikutsa during an Extended Analysis Workshop in Zimbabwe in June 2017. Additional thanks go to Mandla Tirivavi for her administrative support to facilitate manuscript writing.

Funding

This paper was developed as an expected outcome for three of the authors who were participants of a DHS Extended Analysis retreat facilitated by MEASURE DHS. The activity was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the MEASURE DHS-III project at ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the governments of the United States or Zimbabwe.

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study comes from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Detailed information on the survey design and characteristics are provided on the DHS homepage, https://dhsprogram.com/Data/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FMM, RGM and HG conceived the study and performed the statistical analysis. PM carried out literature review. FMM and PM drafted the manuscript. FMM, RGM,PM and HG critically revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors were granted approval from the Demographic and Health survey (DHS) Review Board to obtain and use the collected data for analysis. All data were anonymized prior to the authors receiving the data.This study was based on secondary data from the ZDHS 2015 report, it did not involve physical risk on participants and the dataset used did not contain identities of the participants. No humans were interviewed hence there was no physical risk or harm involved.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F., Gunguwo, H., Mandigo, R.G. et al. Predictors of early initiation of breastfeeding among Zimbabwean women: secondary analysis of ZDHS 2015. matern health, neonatol and perinatol 5, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-018-0097-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-018-0097-x