Abstract

The question of how best to classify Modern Standard Chinese loanwords is rather a fraught one. Various principles of categorization have been proposed in the literature; however, previous classification systems have generally covered only a relatively small proportion of all loanwords currently in use. Even attempts to provide an exhaustive catalog of lexical borrowing strategies have often been characterized by non-transparent structure, internal inconsistency or even incompleteness. This has hindered meaningful cross-linguistic comparisons of language change in Modern Standard Chinese vis-à-vis other languages. The aim of this paper is to present a new and clearly structured, comprehensive inventory of the different types of lexical borrowing that have occurred in Modern Standard Chinese over the past 30 to 40 years. Systematic cross-linguistic comparisons reveal that examples of almost all of the categories of lexical borrowing noted in the literature on English language change can likewise be provided in relation to Modern Standard Chinese. In addition, Chinese offers several options for borrowing lexical items not available to speakers of English. Overall, this paper presents a picture of Modern Standard Chinese speakers as cultivating a flexible, creative, playful approach to their use of language. The explicit recognition of the fact that many so-called “alphabetic words” are established loanwords is found to have implications for the typological classification of Chinese script, as well as for other fields such as second language teaching. A secondary finding not anticipated in the research question is that Chinese orthography shows tentative early signs of potentially developing from a morpho-logographic to a phonetic writing system.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Research into contact-induced language change in Chinese

Contact-induced language change has been a popular topic of scholarly inquiry in Chinese linguistics at least since the great linguist Wang Li published a number of works in the 1940s, in which he discussed the “Europeanization” of Chinese grammar (Wang 王力 1984, 1985).Footnote 1 Early treatments of the topic tended to focus on contact-induced changes in word order and syntactic structures. Since the introduction of the open-door policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s and the widespread adoption of increasing numbers of loanwords in Modern Standard Chinese,Footnote 2 however, interest in language change within the field of Chinese linguistics has expanded to include contact-induced lexical change.

It is interesting to note that the important role language and dialect contact have played in recent Chinese language change is a common theme running through the Chinese-language literature (Jing-Schmidt and Hsieh 2019). It is generally agreed that a significant proportion of linguistic developments (lexical as well as grammatical) in Modern Standard Chinese in recent decades fall under the heading of contact-induced change; within this body of research, contact both with other Sinitic dialects and with non-Sinitic languages features prominently. In the literature on lexical change specifically, a favorite focus has been the dramatic increase in the popularity of “alphabetic words,” also known as “lettered words” (defined in the literature as expressions whose written form makes use of at least one Latin letter), with many historical linguists entering into lively debate on the desirability or otherwise of the use of these novel expressions in Chinese writing. Other classes of loanwords (loan translations and transliterations) have not excited nearly as much controversy. Nevertheless, it is probably fair to say that in the Chinese-language literature in general, there is a very close link between language change and language planning. Few authors confine themselves solely to observations of language change without feeling entitled or perhaps—one sometimes suspects—obliged to pass judgment on the merits and drawbacks of these changes and to point out implications for language planning, some even going so far as to suggest amendments to current language planning policies.

1.2 Shortcomings of previous classification systems

There is certainly no dearth of publications on Chinese lexical change; nevertheless, these are not always as useful or as insightful as one might hope. Much of the existing literature comprises shallow and unsystematic treatments, consisting largely of ad hoc observations with disappointingly few genuine attempts to provide a comprehensive analysis of the findings, to tie them in with previous research, or to elucidate how they contribute to the overall picture. Of the classification systems previously proposed in the literature on Chinese lexical change, the majority are incomplete, some are internally inconsistent, a few contain classification criteria that are irrelevant for their intended purposes, many are poorly structured, and few are applicable to other linguistic contexts. Concrete examples of these flaws will be provided at appropriate points during the discussion of the analysis and findings (see Section 3.1 Proposed system of classification).

1.3 Purpose of this paper

The purpose of this study is twofold. The first objective is to introduce a new classification system for the different types of lexical borrowings that have entered written and spoken Modern Standard Chinese over the past three decades or so. With a view to broadening the relevance of this research, it is hoped that the classification system thus devised can with appropriate modifications likewise be applied to other languages and linguistic situations and in the process help provide some basis for a universalist approach to loanword classification. The second goal is to demonstrate, with the help of the new classification system developed here, that Modern Standard Chinese currently makes use of a greater arsenal of strategies for borrowing words than does English.

2 Data and methodology

2.1 Data

The primary data required for this research were examples of loanwords in Modern Standard Chinese. These were drawn in the first instance from the academic literature on Chinese language change; other supplementary data were also collected from publicly available lists of neologisms (including loanwords) compiled by lay people with an interest in recent lexical developments. Recent real-life examples of the use of such loanwords were generally obtained by conducting internet searches. For the comparative section of this paper, examples of loanwords in English were also required. These were similarly sourced from the academic literature on lexical change in English.

Of course, not all neologisms are loanwords. Speakers of any language are perfectly capable of expanding the lexicon of their mother tongue without necessarily having recourse to linguistic elements adopted from other languages. In the case of Modern Standard Chinese, it has been observed that even new words containing Latin letters (so-called “lettered” or “alphabetic words”) should not necessarily be analyzed as loanwords since they are sometimes novel creations on the part of Chinese speakers (Cook 2014; Ding et al. 2017; Huang and Liu 黄居仁,刘洪超 2017). Cook (2014) isolates three types of Modern Standard Chinese neologisms using Latin letters that are nevertheless deemed to be examples of lexical coinages rather than lexical borrowing; according to the classification system proposed in that study these include novel English expressions (e.g., love hotel), initialisms of Chinese (e.g., RMB; LKK) and Chinese initialisms of English (e.g., GF 'girlfriend'; BF 'boyfriend').Footnote 3

It should be highlighted that not all novel lexical items having their origin in another language were deemed to fall within the scope of this research. A borrowed word, for example, may be used once by a single speaker in a single communicative context and never appear again. (This is known as a nonce loan, or ad hoc loan—refer to discussion on clarifying terminology in Section 3.1.1 below.) Such lexical innovations, while they may be of linguistic interest for a variety of reasons, are not dealt with in this paper.

For the purposes of delimiting the range of data under consideration, it was assumed that all examples of lexical change appearing in Chinese academic publications would have attained a sufficient degree of popularity, frequency of use, demographic spread, and genre coverage to qualify as established neologisms, as opposed to merely being isolated examples of ad hoc usage. In the case of novel expressions gleaned from lists assembled by non-linguists, the author’s own intuitive sense of what were established neologisms was substantiated by the corroborative opinions of native speaker consultants, as well as by Google searches confirming their widespread use, at least in online texts.

2.2 Methodology

The strategy adopted in this paper is to try, as far as possible, to apply a mechanical approach to the analysis of different types of neologisms. That is to say, different categories are defined largely in terms of the processes undergone in borrowing and (where relevant) forming the new words in question, as well as the internal structure of these words and, in some cases, their orthographic representation and spoken realization.

Of course, it would, in theory, be perfectly possible to adopt a number of quite different strategies. These could include assigning new loans to different subclasses based on their language of origin; classification of loanwords according to semantic field; categorization of lexical borrowing fundamentally in terms of internal vs. external change; investigation of the semantic, structural, or other impact of new developments; or even an analysis of the different types based on the perceived reason for their existence and the factors contributing to their attractiveness and/or usefulness to users of the language.

However, the mechanical approach was chosen for a number of different reasons. Firstly, it was felt that a system of classification purporting to facilitate cross-linguistic comparisons should, as far as possible, be equally easy to apply to all languages. Secondly, it was hoped that distinctions of a purely mechanical nature would be more likely to be reasonably straightforward and less likely to be controversial. Thirdly, it was suspected that since some of the mechanical procedures used to arrive at certain Chinese neologisms are quite complex and fascinating, they might also prove to be relatively unusual. Thus, it was anticipated that a detailed analysis of these would not only promote deeper insights into some of the sociolinguistic conditions prevailing in Chinese-speaking communities but might also reveal rather interesting cross-linguistic comparisons.

3 Research findings

This section is divided into two main subsections. The first illustrates various different types of lexical borrowing in Modern Standard Chinese by means of a number of real-life language examples and follows this up with the author’s proposal for a logical and structured system of classification capable of facilitating both fine-grained monolingual analysis and multilingual cross-linguistic comparisons. In the second subsection, the proposed system of classification is applied to loanwords in English, thereby enabling a comparison between Modern Standard and English with respect to the different methods of borrowing lexical items employed in those two languages.

3.1 Proposed system of classification

3.1.1 Clarification of terminology

Before presenting to the reader the proposed classification system, it is worth making a short digression to discuss the distinction between code-switching (or code-mixing) and borrowing on the one hand and between ad hoc use and established use on the other. What are here termed “borrowed words” are often classified (either explicitly or by implication) as “code-switching” in the Chinese-language literature (Chen W. 陈万会 2005; Guo 郭文静 2005; Li 李楚成 2003; Qi 祁伟 2002); however, that particular use of the term code-switching is clearly at odds with the way it is understood in the Western literature on contact linguistics. In the following paragraphs, some common terms, their definitions in the Western literature, and their application in the context of English are all outlined before discussing how best to apply the terminology to language change phenomena in Modern Standard Chinese.

In the Western literature on contact linguistics, particularly literature dealing with the use of L2 expressions in L1 sentences, distinctions are generally made on two levels: between code-switching and borrowing on the one hand and between ad hoc use and established use on the other (Clyne 2003; Myers-Scotton 2002; Poplack 2018; Poplack and Dion 2012; Thomason 2003). These two dichotomies combine to produce four different categories in total: ad hoc code-switching, established code-switching, ad hoc loans (also known as nonce borrowings), and established loans.Footnote 4 As with so many models, these categories are easier to define in theory than in practice, and it is not uncommon in everyday language use to find many examples of expressions which are borderline cases or which appear to be in the process of developing from one category to another. Nevertheless, for the purposes of linguistic analysis, it can be helpful to use these categories as a starting point for discussion.

It is generally accepted in the Western literature that a borrowed word is treated grammatically as an integral part of L1, whereas an L2 expression whose internal structure remains true to the morpho-syntax of the source language and which resists grammatical integration into the L1 context in which it is found is considered to be an example of code-switching (Poplack 2018). There is a less obvious correlation with phonology, inasmuch as a borrowed word is more likely to undergo phonological assimilation to L1, while expressions used in code-switching are less likely to; however, the level of fluency attained in L2 by the individual speaker will probably play a significant role here as well. Another way of summarizing these observations is that borrowed expressions are adopted or adapted, whereas L2 expressions used in code-switching remain essentially “foreign” and are normally regarded by the speakers who use them as such, even when they pass into established use.

As regards the distinction between nonce, or ad hoc loans and established loans, the former are typically used in a single communicative (written or spoken) context by a single speaker, while the latter are used repeatedly by various speakers. Ad hoc use of L2 expressions, whether code-switching or borrowing, presupposes fairly extensive knowledge of L2 and is therefore most likely to occur in communication between bilinguals. It is also much more likely to occur in the spoken than the written language; if it does appear in the written language, it is generally highlighted by means of stylistic conventions such as italicization. Ideally, of course, to qualify as an established loan, an expression should be used by a significant proportion of the speech community and across a range of genres. Of course, a nonce borrowing that “catches on” may progress to the status of an established loan; in fact, it is probably fair to say that many, if not most expressions classified as established loans today started life as nonce loans (Heath 1989; Myers-Scotton 1992, 2002; Romaine 1989; Thomason 2003). As with neologisms in European languages, which tend to appear in italics until they gain widespread usage and acquire nativized status, Chinese neologisms often spend the initial phase of their life cloaked in inverted commas before being considered established enough to be allowed to appear in Chinese-language texts without the highlighting effect.

If we apply the aforementioned definitions to a hypothetical situation in which, say, English is L1 and French L2, then the various distinctions outlined above can be illustrated by means of concrete examples. Thus, ad hoc code-switching might occur in a conversation between bilinguals, in which one speaker, searching for the right English expression, inserts the aside comment dit-on en anglais in the middle of an English sentence. Established code-switching, on the other hand, might include such readily comprehensible sentences as “She has a certain je ne sais quoi.” The internal structure of both these French phrases conforms to French morpho-syntactic conventions; however, the first is considered an isolated occurrence (notwithstanding the fact that it has probably been used on many an occasion by native French speakers trying to communicate in English), whereas the second is an expression in reasonably common use in English and—crucially—is used even by people who otherwise speak very little French at all. In the Western literature, code-switching is a term that tends to be applied to phrases or sentences, rather than single words. This is hardly surprising when one remembers that part of the definition of code-switching is that linguistic material from L2 retains the grammatical features of the source language and is not morphologically or syntactically integrated into L1.

Ad hoc borrowing, like ad hoc code-switching, is most likely to occur in a conversation between bilingual speakers and might include the isolated use of specialist terminology. For example, a conversation in Sinhala between two Sri Lankan engineers working for an international company might be peppered with English expressions such as measuring device, binary switch, component, etc. Established loans, by contrast, include words that are familiar to the majority of monolingual English native speakers, such as café and naïve. These are so well integrated into English that they are subject to the same rules of inflexional and derivational morphology as autochthonous words, producing such variants as cafés and naivety.

It is worth observing at this juncture that French loanwords such as café, déjà vu, naïve, and tête-à-tête, which are now firmly ensconced in the English lexicon, nevertheless typically appear in written English with diacritics that are not considered part of the standard English writing system. That is, the use of non-autochthonous orthographic conventions is not necessarily a barrier to classification as an established loanword.

If we now consider a different linguistic context, namely, one in which L1 is Modern Standard Chinese and L2 is English, then we can likewise find concrete examples to illustrate the four different categories under discussion. Ad hoc code-switching is likely, again, to occur in a conversation between bilinguals. An example of this might be an international student from China inserting the English name of a university subject or degree course (e.g., Chinese-English business translation) into a Chinese sentence in conversation with a fellow student. Established code-switching includes the use of expressions like say hello in the middle of Modern Standard Chinese utterances. In making this distinction, the principle is the same as for other linguistic situations. The internal structure of both expressions conforms to English grammatical conventions; however, the former expression is an isolated occurrence in communication between two bilinguals, whereas the latter is used repeatedly even by essentially monolingual speakers. Ad hoc borrowing, which, like ad hoc code-switching, will typically occur in bilingual communication settings, may include the one-off use of an expression such as solvent, devaluation, hypothermia, and other work-related technical jargon. Established loans include such commonly occurring and grammatically well integrated words as case, fans, happy, pass, size, and sorry. These distinctions, if they are made at all in the Chinese-language literature, are often not made explicitly, nor are they generally in line with the understanding of these terms in the Western literature.

One can speculate as to possible reasons for the widespread misclassification of borrowed words in the Chinese-language literature. Some Chinese linguists may be slow to recognize the possibility that Modern Standard Chinese could be written in any form other than characters. It has been claimed that the introduction of Latin letters into the Chinese writing system is the most significant innovation in Chinese orthography since the abolition of seal script some 2000 years ago, and it is possible that this momentous realization has not yet penetrated into all corners of Chinese linguistics. Another, related possibility is that the historically and culturally determined precedence of written over spoken norms has hindered the recognition of foreign-looking elements as an integral part of the modern language. Of course, one should also mention the more conservative approach to language use prevailing in Chinese society generally and apparently also affecting Chinese linguistics. In particular, there seems to be a strong desire to uphold notions like “language purity” and “correct usage” or at least “judicious use,” as demonstrated in many researchers’ comments and suggestions on language planning issues (Chen C. 陈彩珍 2005; Guo and Zhou 郭鸿杰,周国强 2003; Jin 金其斌 2005; Li 李宝贵 2001; Qi 祁伟 2002; Wang 王崇义 2002; Wang and Li 王玉华,李宝席 2003; Wen and Liu 温珍琴,刘善权 2004). Another factor worth commenting on is the term used for code-switching or code-mixing in Chinese: 语码转换 yǔ-mǎ zhuǎn-huàn code-switching. Although this is a perfectly reasonable rendering of the English term, the use of the character 码 mǎ “symbol; code” may well reinforce the view which for numerous historical and cultural reasons is probably already reasonably prevalent amongst Chinese linguists, namely, that it is the written form of the language that provides the basis for decisions as to what is a valid component of the language and what is not.

Despite the reasonably widespread consensus in the Chinese-language literature on language change regarding the use and application of the term语码转换 yǔ-mǎ zhuǎn-huàn ‘code-switching’, a conscious decision was made to follow the Western rather than the Chinese understanding of code-switching. It was felt to be important for the purposes of this study to employ the contrasts between code-switching and borrowing on the one hand and between ad hoc and established use on the other as they are employed in the Western literature on contact linguistics. For all the reasons outlined in this section, it was decided to analyze the appearance of many so-called “lettered words” or “alphabetic words” in Chinese sentences not—as is generally the approach in the Chinese-language literature—as examples of code-switching or nonce borrowing, but rather as examples of established loanwords, that is, as words that now belong to the lexicon of Modern Standard Chinese. For the purposes of this classification system, only expressions deemed to satisfy the criteria for established loans are considered for analysis.

3.1.2 Classification of various types of loans

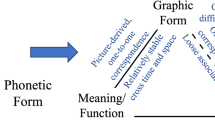

It is proposed that neologisms that have been adopted into Modern Standard Chinese from another language be classified according to which elements of the model word or expression in the donor language are borrowed. In theory, it is possible to borrow three elements of a word either separately or in combination with one another: the meaning (M), the (written) form (F), and the pronunciation (P). In practice, these elements are not all equally likely to be borrowed, with the meaning being the component that lends itself most readily to borrowing.

To illustrate this principle, we can think of the English word “bikini” as being made up of three components, as follows:

-

Pronunciation (P): /bǝki:ni/

-

Written form (F): “bikini”

-

Meaning (M): two-piece bathing suit for women, usually designed to reveal as much leg, midriff and cleavage as decently possible.

When borrowed into Chinese, this expression has essentially retained both the meaning and the pronunciation—although with some modification to conform to the phonological rules of the borrowing language (as discussed below), being realized in Modern Standard Chinese as /pi ʨ ini/. Note that the written form has not been borrowed along with the other two components; rather, this particular loanword is written using autochthonous Chinese script. This principle can be applied equally well to loans from other languages; for instance, the French word 'champagne' was borrowed into Chinese as 香槟 xiāngbīn, while the Korean word 'oppa' has been adapted to 欧巴 ōubā (both clearly modeled on but showing some phonological divergence from their respective source languages). This type of borrowing is known as a transliteration; other types of loanwords borrow other combinations of the three elements defined above.

It is an interesting feature of loans generally in language contact situations around the world that they frequently undergo some modification to the meaning and/or pronunciation during the borrowing process, and Modern Standard Chinese is no exception to this (cf. Ding et al. 2017). Since loans are often (but by no means always) adopted from L2 to fill a perceived “gap” in the lexical resources of L1, the semantic designation of the borrowed expression may shift slightly to fit around or between existing semantic designations in L1. A relatively well-known example of this is the loan word angst, which in its donor language German is used in a very general sense to refer to fear of any kind but which is used in English in a much narrower sense to refer to psychological fears or hang-ups. To take an example in the opposite direction, the English word job has been borrowed into German to refer primarily to paid work of a temporary or casual nature, while the autochthonous German word Arbeit is used more generally for any kind of work.

Similarly, it is not uncommon for the pronunciation of the loanword to be modified, usually in such a way that it conforms to—or at least deviates less from—the phonological rules of the borrowing language L1. As intimated in Section 3.1.1 above, there is often more than one acceptable or standard pronunciation for a borrowed expression, with the pronunciation that is closer to the donor language generally being favored by those speakers of L1 who are also fluent in L2, while the pronunciation that conforms more closely to the phonological rules of the borrowing language tends to be used by monolingual L1 speakers. For example, the Japanese loan tsunami can be pronounced in English with the word-initial affricate /ts/ or the fricative /s/, this language variation essentially being a matter of individual speaker choice.

Likewise, loanwords adopted by Chinese speakers also often undergo some change to the meaning and/or pronunciation, resulting in minor but noticeable semantic and/or phonetic divergences from the donor language. This does not detract from the fact that both these elements of an expression (i.e., both the meaning and the pronunciation) can be borrowed, either separately or in combination—even if they are borrowed “imperfectly,” as it were.

Detailed analysis of the data from Modern Standard Chinese reveals quite a large number of different categories of lexical borrowing. Firstly, it is possible to borrow the meaning alone. These borrowed expressions are referred to in the English-language literature as calques or loan translations. It is equally possible to borrow the meaning in combination either with the form or with the pronunciation: the former type is classified in the Chinese-language literature as Japanese loans and in the present study as “symbolic loans,” while the latter type is known in both the English-language literature and the Chinese-language literature as transliterations. In Modern Standard Chinese, somewhat surprisingly perhaps, it seems also to be possible to borrow the form and pronunciation without the meaning. In the classification system proposed here, this type of neologism is termed a “graphic loan.” Then, of course, it is possible to borrow the three elements of meaning, form, and pronunciation simultaneously. Such neologisms are referred to under the current classification system as “wholesale loans.” Finally, in Modern Standard Chinese, there are a number of new expressions which make use of two or more different borrowing strategies within a single word or expression. These are referred to as “hybrids.” To summarize, neologisms entering Modern Standard Chinese primarily by means of borrowing (as opposed to creating, Cook 2014) can be divided into calques, symbolic loans, transliterations, graphic loans, wholesale loans, and hybrids. These will be discussed in turn in the following.

We first consider an example of a calqued expression.

-

(1)

其实,当我事业遇到瓶颈的时候,我也很烦恼……Footnote 5

Qíshí,__dāng__wǒ__shìyè__yùdào__píng-jǐng__de__shíhou,__wǒ__yě__hěn__fánnǎo …Actually,__when__1SG__career__encounter__bottle-neck__ATT__time,__1SG__also__very__worried ….Footnote 6

Actually, I was worried too when my career wasn’t going anywhere …

Clearly, this is an example of a loanword that has borrowed only the meaning from the source language; the written form and pronunciation are essentially “Chinese.” This particular example is an example of what is sometimes referred to in the Chinese-language literature as a “partial calque”: in other words, each individual morpheme (or sometimes word) in the model expression has been translated into an equivalent morpheme (or word) in the borrowing language.Footnote 7 Further examples of partial calques include白领 bái-lǐng 'white-collar', 代沟 dài-gǒu 'generation gap', 峰会 fēng-huì ‘summit meeting’, 连锁店 liánsuǒ-diàn ‘chain store’, 软饮料 ruǎn-yǐnliào ‘soft drink’ and 热狗 rè-gǒu “hotdog’.

By contrast, it is also possible to borrow the meaning of an expression not by providing a morpheme-by-morpheme translation of individual components, but by translating the meaning of the expression as a whole: these are often referred to in the Chinese-language literature as ‘holistic calques’. Examples of holistic calques include 电话 diàn-huà electric-speech ‘telephone’, 电脑 diàn-nǎo electric-brain ‘computer’, 电影 diàn-yǐng electric-shadow ‘movie’, 双赢 shuāng-yíng double-win ‘win-win’, 自助餐 zì-zhù-cān self-help-meal ‘buffet’ and 盗版 dào-bǎn steal-publish ‘to pirate’. It is worth observing that an explicit distinction between “holistic” and “partial” calques is rarely made in the Western literature. Analyzing the examples of different classes of neologisms cited in the Western literature, it seems that as a general rule only so-called “partial calques” are treated as calques in the Western literature, while what are classified here as “holistic calques” tend to be considered as examples of compounding (i.e., not classified as borrowing at all).Footnote 8

Next, we look at an example of the type of borrowing that in the Chinese-language literature is generally referred to as a “Japanese loan” but for which this paper uses the more widely applicable term “symbolic loan.” As explained above, symbolic loans borrow a form-meaning combination without the associated pronunciation. To illustrate the principle, less recent examples of symbolic loans in Chinese are the Arabic numerals. These were first adopted during the Yuan Dynasty and have largely replaced the autochthonous Chinese numeric representation system in a wide range of contexts, although the original characters are still available for use and remain optional or even preferred in a number of settings. The class of symbolic loans is, incidentally, the category to which Arabic numerals likewise belonged when they were first adopted into common use in European languages. An example of a more recent symbolic loan in Modern Standard Chinese is provided in (2).

-

(2)

医生の话,孩子总是很信の(就像他们很信任警察叔叔一样)。Footnote 9

Yīsheng__de__huà,__háizi__zǒng__shì__hěn__xìn__de__(jiù__xiàng__tāmen__xìnrèn __jǐngchá__shūshu__yíyàng).

Doctor__ATT__speech,__child__always__COP__very__believe__NOM__(just__like__3PL__trust__police__uncle__same).

Children always believe what doctors say (the same as they trust police).

This written form has been adopted in a number of genres, notably internet websites and popular magazines, as a substitute for the autochthonous written form 的 de, a grammatical particle with many uses including marking possessives, attributes, and nominalized forms. The borrowed form seems to appear in all three grammatical functions in Modern Standard Chinese, even though the range of functions performed by の no in Japanese is more limited. One can hypothesize that the popularity of this symbolic loan is due in part to the fact that it is easier and quicker to write (that is, it is possible that it crept in first through hand-written communication) and in part to a number of sociolinguistic and cultural factors including the general popularity of all things Japanese. Another factor favoring its widespread acceptance, at least in Taiwan, is that since there is no Mandarin Chinese cognate for the Southern Min attributive or possessive morpheme, ê, there is no obvious choice of Modern Standard Chinese character to represent this grammatical morpheme when writing Southern Min.Footnote 10 This, coupled with the pervasive influence of Japanese culture in Taiwan from the period of colonization through to the present, may well have been a sufficient consideration to ensure the linguistic success of の de/ê in Taiwan, from whence it seems to be spreading to other Chinese speaking regions.

Symbolic loans borrowed from Japanese are probably less common today than they were a century ago, when significant numbers of technical, political, and cultural terms were adopted from Japanese into Chinese in the wake of the May Fourth Movement. Examples still in common use today include 革命 gémìng ‘revolution’, 文化 wénhuà ‘culture’, 社会 shèhuì ‘society’, 科学 kēxué ‘science’ and 系统 xìtǒng ‘system’ (Gunn 1991; Masini 1993; Norman 1988).Footnote 11

What is particularly interesting about this class of loans from a historical perspective is that most of the ones borrowed around the time of the May Fourth Revolution can in fact be viewed as originating in the Classical Chinese of many centuries or even millennia ago. With a number of these compounds, their first attested use in that particular combination in fact occurs in Chinese (not Japanese) texts; however, the Classical Chinese usage generally did not carry the same connotations or even denotations as the modern term, nor would the (in most cases disyllabic) expression necessarily have been considered a single word in Classical Chinese—it may have been a noun-noun phrase, an adjective-noun phrase, or a verb-object phrase. With other expressions, their use as a disyllabic compound or phrase is not attested but merely suggested by extant Classical Chinese texts.

The key point is that these expressions were sourced from Classical Chinese by Japanese scholars, politicians, and scientists looking for ways of expressing essential “new” concepts during the era of rapid modernization that took place in Japan in the nineteenth century and popularized in Modern Japanese. In so doing, the Japanese not only borrowed Chinese lexical and orthographic resources, but also pieced the elements together in ways that generally conformed to the word-internal morpho-syntactic rules of Chinese. When China underwent a similar process of drastic transformation several decades later and likewise discovered the need to express certain concepts indispensable to modernization, many of these predominantly disyllabic kanji expressions were “borrowed” back into Chinese to fill a perceived gap, often without the borrowers even necessarily realizing that the terms were in fact in some cases obsolete autochthonous expressions.Footnote 12 Understandably, the fact that the terms had been coined using Chinese lexical and morphological elements rendered them more palatable to the general populace than some of the rival transliterations in vogue at the time, such as 德谟克拉西 démókèlāxī ‘democracy’ (Gunn 1991). In view of the somewhat checkered history of some of these terms, it is debatable whether they should in fact be assigned to a separate class of their own. However, it was decided for the sake of simplicity to keep them within the class of “symbolic loans,” bearing in mind that this paper explained at the outset that loans would be categorized according to the mechanical processes of borrowing at the point of entry into L1.

Note that the use of the Japanese hiragana の no in the sense of Chinese 的 de naturally feels more “exotic” than the use of polysyllabic Japanese compounds because hiragana script is not autochthonous to Chinese—unlike the characters in use in Japanese, which were originally borrowed from Chinese. Nevertheless, the underlying principle is essentially the same. Although the individual component characters of the expressions given above had all existed in Chinese for centuries, if not millennia, the disyllabic Japanese compounds borrowed into Chinese about a century ago did not exist previously in that particular combination in Modern Standard Chinese. Nor (owing to the frequent discrepancy in meaning of a given character as it is used in Chinese and Japanese) would the compounds in question necessarily have been understood to have those particular semantic designations without the model provided by Japanese. It is on these grounds that we can say that they represent the borrowing of a form-meaning combination.

In the Chinese-language literature, it is common to list a number of single characters as examples of Japanese loans as well (e.g., Jiang 1999). Two of the best known monosyllabic “Japanese loans” are 风 fēng and 族 zú, whose semantic designations have bifurcated in recent years under linguistic pressure through contact with Japanese from the original Chinese meaning of ‘wind; style’ to ‘fashion; trend; craze’ and from ‘nation’ to ‘group; collective; clan’ respectively. Popular expressions availing themselves of these new meanings include 奥林匹克风 Àolínpǐkè-fēng ‘Olympics craze’, 中国风 Zhōngguó-fēng ‘China craze’, 工薪族 gōngxīn-zú wage-clan ‘wage earners’, 绿卡族 lǜ-kǎ-zú green-card-clan ‘green card holders’ and 隐婚族 yǐn-hūn-zú conceal-marriage-clan ‘people who conceal their married status and claim to be single’. However, it seems as though the processes—or at least the effects—of the two types of linguistic influence emanating from Japan are different inasmuch as monosyllabic Japanese character loans result in the reassignment of a new meaning to individual Chinese characters, whereas polysyllabic Japanese compounds do not.Footnote 13 It therefore makes more sense to classify monosyllabic “Japanese loans” not as loanwords but as examples of contact-induced semantic change (bifurcation).Footnote 14 That being the case, strictly speaking they do not fall under the scope of the present system of classification.

There is a sense in which the process for borrowing Japanese compounds into Modern Standard Chinese is in fact little different from that involved in intra-Chinese loans (new compounds borrowed from other Sinitic languages and dialects). As with symbolic loans borrowed from Japanese, intra-Chinese loans are polysyllabic compounds whose written form and meaning are simultaneously borrowed into Modern Standard Chinese, while the pronunciation is not. With both Japanese symbolic loans and intra-Chinese loans, the pronunciation of the individual syllables in the source language (or dialect) may be quite different from the pronunciation in the borrowing language (or dialect). The main difference is that with Japanese loans the meaning of the individual components may diverge considerably from the meaning understood in Modern Standard Chinese, so that the meaning of the whole may be less easily derived from the meaning of the compositional elements.

Next, we consider a couple of examples of transliterations, remembering that these are loanwords that borrow a sound-meaning combination from the donor language without borrowing the written form.

-

(3)

呵呵,有什么问题发伊妹儿给我啦!Footnote 15

Hēhē,__yǒu__shénme__wèntí__fā__yī-mèi-ér__gěi__wǒ__la!

Haha,__have__any__question__send__3SG-little:sister-son__BEN__1SG__MP!

Haha, if you've got any questions just flick me an email !

As can be seen from the interlinear gloss, the component characters that make up this transliteration mean something like ‘s/he’, ‘little sister’ and ‘son’. These clearly have nothing whatsoever to do with the meaning of “email” and have been chosen purely for their phonetic reading to produce a transliteration whose Modern Standard Chinese pronunciation is as close as possible to the original English word. As such, example (3) is what is known as a “pure transliteration.” Likewise, the characters chosen for the following transliterations do not bear any relation to the overall meaning of the word either 比基尼 bǐ-jī-ní compare-foundation-Buddhist:nun ‘bikini’, 麦克风 mài-kè-fēng wheat-gram-wind ‘microphone’ and 三明治 sān-míng-zhì three-bright-govern ‘sandwich’.

For comparison, let us now consider in sentence (4) an example of a slightly different type of transliteration.

-

(4)

现在托福好不好考?Footnote 16

Xiànzài__tuō-fú__ hǎo-bù-hǎo-kǎo?

Now__rely:on-luck__good-NEG-good-sit:a:test?

Is it easy to do well on the TOEFL test now?

This time we see that the meanings of the individual characters chosen to form this transliteration translate as ‘rely on’ and ‘luck’. Obviously, the characters have been selected not only for their phonetic value, to produce a disyllabic Modern Standard Chinese word that bears a strong phonological resemblance to its English model, but also for their semantic value.Footnote 17 The differences between these two subclasses of transliterations have sometimes been overlooked in the Chinese-language literature on lexical change (e.g., Tang 汤志祥 2003). However, examples of the latter type have been referred to in the English-language literature as phono-semantic matches (Zuckermann 2003, 2004).

Many brand names, place names, and even product names fall into this category. Examples include 奔驶 bēn-shǐ speed-drive ‘Benz’.Footnote 18 美国 Měi-guó beautiful-country ‘America’ and 可口可乐 kě-kǒu-kě-lè appeal:to-mouth-make-happy ‘Coca-cola’. In fact, it is probably fair to say that no foreign enterprise trying to break into the Chinese market can expect to succeed without a convincingly auspicious phono-semantic rendering of its name. Examples of everyday lexical items include 基因 jī-yīn basic-cause ‘gene’, 脱口秀 tuō-kǒu-xiù blurt-mouth-show ‘talk show’ and 维他命 wéi-tā-mìng preserve-3SG-life ‘vitamin’, with the phono-semantic match 黑客 hei-ke black-guest ‘hacker’ being perhaps the most oft-cited example.

Within the class of transliterations there is another subclass referred to in this classification system as “combination transliterations.” Although not all Chinese linguists distinguish between these and phono-semantic matches (e.g., Wang 王崇义 2002), they are in fact constructed according to quite different principles. As the name suggests, combination transliterations are expressions consisting of a transliterated component in combination with another component, which may be either an explanation or a translation. In the case of the “transliteration + explanation” subclass, the entire original expression from the donor language is transliterated and then attached to an autochthonous component that expresses some element of the meaning of the entire expression. Examples of this type include 艾(爱)滋病 ái(ài)zī-bìng AIDS[tr.]-disease 'AIDS', 保龄球 bǎolíng-qiú bowling[tr.]-ball ‘bowling’, 丁克家庭 dīngkè-jiātíng DINK[tr.]-family ‘DINK’ and 桑拿浴 sāngná-yù sauna[tr.]-shower ‘sauna’. In the case of the “transliteration + translation” subclass, only part of the original expression from the donor language is transliterated, while the remainder is translated. Examples of this type include 蹦极跳 bèngjí-tiào bungee[tr.]-jump ‘bungee jumping’,Footnote 19 迷你裙 mínǐ-qún mini[tr.]-skirt ‘miniskirt’, 摩托车 mótuō-chē motor[tr.]-vehicle ‘motorcycle’ and 因特网 yīntè-wǎng inter[tr.]-net ‘internet’). An example from French that has been borrowed along similar principles is 古龙水 gǔlóng-shuǐ cologne[tr.]-water ‘eau de cologne’. While some might cavil at the distinction between various subtypes of combination transliterations as unnecessarily pedantic, in fact in the context of Modern Standard Chinese it is a useful one to make; unfortunately, this distinction has not always been made clear in the Chinese-language literature (Guo 郭鸿杰 2002a, 2002b; Tang 2003; Wang et al. 王辉等 2004; Zhang 张静 2005).

Now let us consider three examples of what in this classification system are termed “graphic loans.” As explained above, graphic loans borrow both the (written) form and the pronunciation of a word from another language but, interestingly, not the associated meaning. Let us see how this works in practice by considering examples (5) to (7) below.

-

(5)

國民黨A了多少錢?Footnote 20

Guómín-dǎng__A-le__duōshao__qián?

National-party__misappropriate-PFV__how:much__money?

How much money have the Nationalists misappropriated ?

This type of loan is known as a “phonetic representation” in the present classification system. In this particular case, the use of a Latin letter to represent the phonetic value of a Taiwan Southern Min word that has no cognate in Modern Standard Chinese has been eagerly adopted by Mandarin speakers in Taiwan. A similar example, also used to represent a Southern Min expression, is given in (6).

-

(6)

重庆毛血旺里有一种很透明吃起来很Q的包子……Footnote 21

Chóngqìng__Máoxuèwáng__lǐ__yǒu__yī__zhǒng__hěn__tòumíng__chī-qilai__hěn__Q__de__bāozi ...

Chongqing__Maoxuewang__in__EXST__one__type__very__transparent__eat-INCH__very__elastic:and:chewingful__ATT__dumpling …

Chongqing’s local cuisine has a type of dumpling that’s transparent and very elastic and chewingful …. Footnote 22

Note that the two preceding examples represent Taiwanese usage. In mainland China, the graphic loan in (6) is likewise quite common in both written and spoken Modern Standard Chinese. However, the pronunciation differs slightly in that it is pronounced in the first tone in Taiwan and the fourth tone in mainland China. The semantic designation is also different, as it is used in mainland China in the sense of “cute,” to which it bears a strong phonological resemblance, particularly for speakers of a language lacking syllable-final stops.

The next example, like the two preceding examples, is classified as a graphic loan because it borrows the form and pronunciation of an English word without the meaning. However, this time the English expression has a meaning of its own, such that the meaning in the donor language and the meaning signified by the expression when used in the borrowing language form a stark and surprising contrast. Indeed, this shock effect is part of the attraction of using such expressions. For their amusement value, they are referred to in this classification system as “graphic puns.”

-

(7)

她沒跟我們來唱歌真是taxi啦。Footnote 23

Tā__méi__gēn__wǒmen__lái__chàng__gē__zhēnshi__taxi__[≡ tài__kěxī]__la.

3SG__NEG__COM__1PL__come__sing__song__really__taxi__[≡ too__shame]__MP.

It’s such a pity she did not come and sing with us.

In this example, the English written form taxi has been assigned a different semantic value based on its phonological resemblance to a common Modern Standard Chinese expression, 太可惜 tài kěxī ‘what a pity’. The graphic loan morning call operates on the same principle, with the phonologically similar Modern Standard Chinese expression this time being 模拟考 mónǐ-kǎo ‘practice exam’. The explanation for the graphic loan FBI, a favorite in Taiwan, is somewhat more complicated. FBI is an abbreviation of the pinyin representation fěn bēi’āi of the three characters 粉悲哀, literally ‘powder tragic’, which of course is meaningless. In order to decipher this code, one must bear in mind that owing to L1 interference from Taiwan Southern Min, L2 speakers of Mandarin in Taiwan often realize syllable-initial /h−/ as /f−/. Thus, the syllable fěn is here understood to be a peculiarly Taiwanese rendering of hěn, which in this context would be represented by the character 很 hěn ‘very’, making the entire expression 很悲哀 hěn bēi’āi ‘oh, how tragic; woe is me’.

We now come to that most thorough class of loanwords, the ones which borrow a sound-form-meaning combination from the source language. In the present classification system they are referred to as “wholesale loans.”

Wholesale loans are almost invariably discussed in the Chinese-language literature under the umbrella term 字母词 zìmǔcí ‘lettered words’ or ‘alphabetic words’. This term basically includes any expression whose written form in Chinese texts contains at least one Latin letter and unfortunately masks some quite important differences between the various types of words that make up this large and heterogeneous group, differences pertaining to etymology, internal structure and pronunciation. Lettered or alphabetic words have been the subject of research by numerous linguists; indeed, there has been a veritable spate of literature commenting on this language change phenomenon. The term “lettered words” or “alphabetic words” covers a multitude of sins in the literature and thus is clearly in need of careful and structured analysis. As mentioned above, previous research (Cook 2014; Ding et al. 2017; Huang and Liu 黄居仁,刘洪超 2017) has demonstrated that one fundamental distinction that needs to be made is between alphabetic words that are borrowed directly from a European language and those that are coined by native speakers of Modern Standard Chinese. Within each of these two major groups, further subcategorization is also necessary.

Recent years have seen a significant increase in the number of so-called “lettered words”—here used in the general sense to mean not only the class of graphic loans defined above, but also initialisms, acronyms, and letter-character or letter-numeral combinations as well as fully spelt out loanwords. Although such loanwords were initially more common in Hong Kong, their use has now spread to Mainland China, where they have even appeared in relatively well-known and reputable newspapers, including Renmin Ribao (Guo 郭鸿杰 2002b: 3). While the general attitude amongst linguists towards this particular style of lexical borrowing remains ambivalent, with some commentators welcoming their use and others spurning them, it seems that they are here to stay. In fact, more than a decade ago, the 2002 edition of the Xiandai Hanyu Cidian (Dictionary of Modern Chinese) already included 140 lettered words and abbreviations (cf. He 何烨 2004: 129). Now, that figure is many times higher.

Having ascertained that we are dealing here with borrowed words rather than code-switching and with established loans rather than nonce loans (refer to discussion in Section 3.1.1 above), let us now look at some examples in more detail. Wholesale borrowed initialisms like ATM, CD, IT, MBA, and VIP have been in common use for some years now and were, in a sense, the thin end of the wedge. It is certainly possible, if not probable, that their widespread acceptance throughout the speech community was facilitated by their visual and phonological resemblance to Chinese characters. Upper-case Latin letters are, in the right font setting, not dissimilar in size and shape to “square” Chinese characters. Moreover, like Chinese characters, they are (with only one exception) monosyllabic. In fact, one could go even further than that and state that the letters in initialisms, like Chinese characters, often demonstrate a one-to-one correspondence between syllabic, morphological, and lexical boundaries. The next logical step, perhaps, was the adoption of wholesale borrowed acronyms like SARS, whose written form is very similar to initialisms, even if the rules governing pronunciation are different. Finally, wholesale borrowed words like enjoy, fashion, high, pose, and share started to enter common usage in significant numbers.Footnote 24 Let us consider now a wholesale loan whose adoption into Modern Standard Chinese will surprise no one.

-

(8)

請幫我看這樣的行程和住宿O不OK。Footnote 25

Qǐng__bāng__wǒ__kàn__zhè__yàng__de__xíngchéng__hé__zhùsù__O-bù-OK.

Please__help__1SG__see__DEM__kind__ATT__itinerary__ and__accommodation__O-NEG-OK.

Please have a look if this itinerary and accommodation are OK .

It is hardly a source of wonderment that OK, which has been described as the single most successful English word, has possibly achieved the highest degree of nativization of all wholesale loans in Modern Standard Chinese; nevertheless, the degree of grammatical integration demonstrated in this particular example is fascinating. For those not conversant with Modern Standard Chinese sentence structures, this example may require some elucidation. One method of forming yes-no questions in Chinese is to use the structure [Adj-NEG-Adj] or [V-NEG-V]. Thus, for example, we find 大不大 dà-bù-dà big-NEG-big ‘is it big?’ and 贵不贵 guì-bù-guì expensive-NEG-expensive ‘is it expensive?’. For monosyllabic adjectives and verbs, the structure is very straightforward; however, for some disyllabic adjectives and verbs there is an optional variation on the theme whereby only the first syllable is repeated, producing, for example, questions like 漂不漂亮 piào-bù-piàoliang pret-NEG-pretty ‘is it pretty?’ and 可不可以 kě-bù-kěyǐ al-NEG-alright ‘is it alright?’. From the embedded question in (8), it is clear that the loanword OK has been so thoroughly nativized that is it now treated as a separable disyllabic adjective on the model of such autochthonous adjectives.

Another example of the interesting grammatical integration of a wholesale loan appears in (9). This loanword has a nominal function and is marked for number.

-

(9)

作为年轻人心中的偶像,李云迪对待FANS们的态度很友善……Footnote 26

Zuòwéi__niánqīng-rén__xīnzhōng__de__ǒuxiàng,__Lǐ Yúndí__duìdài__fans-men__de__tàidu__hěn__yǒushàn …

As__young-people__in:the:heart__ATT__idol,__Yundi Li__treat__fans-PL__ATT__attitude__very__friendly …

As an idol of young people, Yundi Li has a very friendly attitude towards his fans …

The morphological integration of fans demonstrated here is intriguing as it appears with the Modern Standard Chinese plural suffix, even though the English plural suffix is already attached.Footnote 27 This seems analogous to the case of the English loanword kars, borrowed into Norwegian with the singular denotation of ‘car’ (McMahon 1994: 206). There is a sense in which it can also be compared with madigadi, borrowed into Swahili on the model of the English word with the plural denotation of ‘mudguards’, owing to the fact that for a certain class of nouns plural number is marked grammatically in Swahili by means of the prefix ma-. In other words, madigadi has been reanalyzed as the plural form, while digadi denotes the singular (McMahon 1994: 207). Clearly, reanalysis is not unheard of with wholesale loans.

Sentence (10) provides yet another example of the kind of grammatical integration that can occur with wholesale loans. This time the English loanword, functioning as a verb, has not only had a resultative complement attached to it but has also been passivized.

-

(10)

这种人早就应该被fire掉了。Footnote 28

Zhè__zhǒng__rén__zǎo__jiù__yīnggāi__bèi__fire-diào__le.

DEM__kind__person__early__just__should__PASS__fire-RES__PFV.

That kind of person should have been fired long ago.

Note that sentences (8) to (10), which demonstrate the grammatical integration of three English loanwords functioning as a noun, a verb, and an adjective, are not isolated examples. Google searches conducted in June 2018 returned more than 17,000 instances of bèi fire-diào ‘be fired’, over 50,000 hits for O-bù-OK ‘okay or not’ and more than 300,000 occurrences of fans-men ‘fans’. To misclassify these expressions either as code-switching or as ad hoc usage would be to display a blithe disregard both for sometimes quite startling levels of morpho-syntactic integration and for widespread patterns of language use. The grammatical integration exemplified in (8) to (10), as well as the frequency of use within the speech community prove that these neologisms are not merely code-switching or nonce borrowing but established loanwords (cf. French examples in English, as discussed above in Section 3.1.1). That is, despite their non-Chinese origins, these words are now part of the lexicon of Modern Standard Chinese.

The final subclass under the heading of lexical borrowings is the heterogeneous group referred to here as “hybrids.” These are not only mostly Chinese creations using Latin letters, but also include a small number of borrowed expressions containing a combination of letters and numerals. A rather amusing example is shown in (11).

-

(11)

我叫你不用客气。你3Q所以我就NO Q啦。Footnote 29

Wǒ__jiào__nǐ__bù__yòng__kèqi.__Nǐ__sān__Q__suǒyǐ__wǒ__jiù__no__Q__la.

1SG__tell__2SG__NEG__need__polite.__2SG__three__Q [≡ thank you]__so__1SG__just__no__Q__MP.

I was saying you're welcome. You were, like, thanks , and I was, like, no worries .

This example may be difficult to appreciate without explaining the context in more detail. In an online chat forum, A asked for advice, and B offered some. A then expressed gratitude by writing 3Q, to which B responded with No Q. When A, who was clearly bemused, asked for clarification, B’s explanation was as given in (11). While 3Q is obviously a transliteration of the English thank you following the established convention of reading Arabic numerals in Modern Standard Chinese and Latin letters in English (cf. Cook’s (2014) discussion of numerical substitutions, as well as initialisms and phonetic representations) and perhaps containing a sly dig at many Chinese speakers’ non-native pronunciation of English, the etymology of No Q is harder to explain. It seems that the expression 3Q, having attained a certain level of popularity, has been reanalyzed from a transliteration to a phrase meaning something along the lines of “I offer you three Qs,” to which the culturally appropriate Chinese response is “No, I do not need your Qs.”Footnote 30

In the Chinese-language literature, a distinction tends to be made between hybrids consisting of a mixture of Latin letters and Chinese characters and those consisting of a mixture of Latin letters and Arabic numerals. This distinction has been adopted here—although it is not entirely satisfactory. Some examples of the first subclass include T恤 T-xù T-shirt[tr.] ‘T-shirt’ and BB机 B-B-jī beep-beep-device ‘pager’. The former consists of a direct borrowing of the letter T from the first element of the English expression, combined with a transliteration of the second element. The latter consists of what appears to be an onomatopoeic rendering of the sound produced by the device, written using Latin letters, combined with a single-character explanation of the class of object referred to. Some examples of the second subclass include 3Q (discussed above) and MP3 M-P-sān ‘MP3’, which just misses out on qualifying as a wholesale loan owing to the Modern Standard Chinese pronunciation of the numeral. From this brief list of examples of hybrids, it is obvious that the two-way subdivision of the class is somewhat superficial, as there seem to be several different processes going on here. It is left to future studies to undertake more detailed analysis of the class of hybrid loans in Modern Standard Chinese.

A brief aside on an oft-discussed example is perhaps in order. At first glance, 卡拉OK kǎlā-OK (‘karaoke’) seems also to pose a classification problem; however, it is probably best classified as a straightforward transliteration that demonstrates creative use of writing resources and incidentally supports the thesis that Latin letters are already an integral part of the Chinese orthographical (but not, obviously, morphological) system. The etymology of this term given in Xīn Cíyǔ Dà Cídiǎn, according to which the word as a whole is a transliteration of the Japanese karaoke but the component OK is an abbreviation of the English word orchestra, strikes one as a fanciful piece of fiction. Surely a much simpler explanation is that by the time the word karaoke was adopted into Chinese, the English wholesale loan OK was so widespread and immediately recognizable, both aurally and visually, that it was easier—and possibly cooler, trendier, etc.—to use that combination of Latin letters than to try to find a representation using Chinese characters, especially since the autochthonous phonology of Modern Standard Chinese does not include the syllable kei. It has been pointed out that intense borrowing, especially adoption, can lead to structural change affecting the phonology, morphology, and syntax (McMahon 1994: 209). From a structuralist point of view, and bearing in mind that, according to Aitchison (2001), grammars are most likely to change at the point of least resistance, the addition of this particular syllable is hardly surprising. Modern Standard Chinese syllables tend to occur in minimal pairs contrasted according to the voicing of the syllable-initial consonant. Sets of pairs involving the stops thus consist of /p−/ and /b−/, /t−/ and /d−/, /k−/ and /g−/. In this particular instance, it is possible to find examples of Chinese characters with the following phonetic realizations in Modern Standard Chinese: pēi (e.g., 胚), bēi (e.g., 杯), tēi (e.g., 忒), dēi (e.g., 嘚), and gěi (e.g., 给) but not kei. The addition of OK to the Modern Standard Chinese lexicon thus supplies a gap in the phonological system of the language, as viewed from a structuralist perspective, in much the same way that large numbers of borrowings from French in the sixteenth century supplied a gap in the structure of the English phonological system by providing a partner for the fricative /f/, which had previously lacked such a voiced equivalent in English, even though other fricatives appeared in unvoiced-voiced pairs (i.e., /θ/-/δ/ and /s/-/z/).

In summary, the various subclasses of the large group of Modern Standard Chinese neologisms referred to here as “borrowings” are illustrated in Fig. 1. Note that the boxes in dotted lines are classes which theoretically could or should exist but for which no examples have been found in Modern Standard Chinese. These are loans for which only the written form is borrowed and those for which only the pronunciation is borrowed; the terminology suggested here is “emblematic loans” for the former and “phonetic loans” for the latter. Even though no examples of such loans have been found to date in the literature on lexical change in Modern Standard Chinese, these categories are included in the diagrammatic representation for two reasons. The first reason is for completeness, as it is apparent from the range of possible combinations of the three components of pronunciation (P), written form (F), and meaning (M) that these two types of loan could theoretically exist and may therefore occur in Chinese at some stage in the future. The second consideration is that these two types of loans possibly already exist in other languages.Footnote 31 The shaded boxes indicate the smallest subclass in each branch that has been analyzed in any detail.

3.2 Comparison of borrowing strategies in Modern Standard Chinese and English

In order to facilitate a detailed comparison between Modern Standard Chinese and English of the various strategies employed by speakers to expand the lexicon of the two languages to borrow lexical items, a table has been prepared. This provides an overview of all the smallest subclasses described in the previous section (Section 3.1 Proposed system of classification) and gives examples, where appropriate.

Two differences between Modern Standard Chinese and English neologisms are quite striking. Firstly, the use of non-standard script elements in lexical innovations in Modern Standard Chinese is conspicuous. There does not seem to be any equivalent in twenty-first century English for the various types of so-called “lettered words” in Chinese. It is possible that in scholarly English in centuries past the use of certain ancient Greek words adopted with the Greek written form may have been widespread enough in that particular genre to qualify as established loanwords (as opposed to nonce borrowing). In that case, they were most likely all examples of the subcategory I have termed “wholesale borrowed words” and would in some ways have been comparable to the established use of an ever-increasing number of wholesale loans that we see today in Modern Standard Chinese. However, the language change literature relating to lexical innovations in Modern English does not (to the author’s knowledge) cite any examples of established loanwords whose accepted written form makes use of any script other than the standard English alphabet. For instance, English contains no Japanese loanwords written in hiragana, Chinese loanwords appearing in characters or Russian loanwords written in Cyrillic. Similarly, borrowings from Hindi, Arabic and Greek all appear in their Romanized equivalents. Moreover, even if we accept the proposition that in previous centuries borrowed lexical items whose written form required the use of non-autochthonous script may have been in (relatively) common use in certain genres of written English, it seems in the highest degree unlikely that there were ever any equivalents for the many classes of lexical innovations in Modern Standard Chinese that have not been borrowed wholesale, but nevertheless make use of non-standard script elements. Such classes include symbolic loans, graphic loans (both phonetic representations and graphic puns) and hybrids.

Secondly, there seem to be more possibilities overall for acquiring new words in Modern Standard Chinese than in English, and specifically for borrowing them. Table 1 reveals that several categories of lexical borrowing occurring in Modern Standard Chinese over the last three decades are not represented in developments in English in recent years. These include symbolic loans using non-autochthonous script, some combination transliterations, graphic loans, wholesale borrowed initialisms and acronyms, and hybrids. These will be discussed in turn.

Some types of lexical change are, by their very definition, much more unlikely in a language with an alphabetic writing system. Symbolic loans are loanwords in which both the written form and the meaning are borrowed without the pronunciation. This category of lexical development is much harder to imagine in languages with an alphabet than in those with a logographic script. Nevertheless, one—admittedly not very recent—example of such a loan in English is the German loan BMW (= Bayerische Motorenwerke). The written form and semantic designation are the same in the borrowing as in the donor language; however, the letters are given their native pronunciation in English, rather than imitating the quite different German pronunciation.

Likewise, phono-semantic matches are considerably more likely to be formed either in languages with phono-logographic scripts or in “reinvented” languages (Zuckermann 2004). On the other hand, a similar process to that used in the construction of phono-semantic matches—although arguably a more unconscious, or perhaps subconscious one—seems to take place in so-called “folk etymology.” An example in English is the expression chaise lounge, a kind of nativized variation on the French borrowing chaise longue, which has the advantage of presenting the native English speaker with a reasonably transparent link between the written form and the object in question—albeit one without any historical validity. Another, less common and considerably more radical example is the substitution of Old Timers’ Disease for Alzheimer’s Disease, which again offers a plausible native etymology, as well as having the added advantage from the point of view of many native English speakers of avoiding the complex consonant cluster in the middle of the non-autochthonous word and thus being easier to pronounce. Although folk etymology and phono-semantic matches are portrayed rather differently in the literature, the former being generally assumed to arise from ignorance while the latter is more often depicted as being a product of lexical creativity, in fact objective analysis of the mechanical processes involved in the two types reveals that they are very similar (pace Zuckermann, who claimed that phono-semantic matches were only possible in reinvented languages and languages with a phono-logographic script).Footnote 32 Another way of formulating this similarity is to say that with both types, words are given a kind of autochthonous morphological justification that they do not inherently possess. Whether the expressions thus formed are a product of ignorance or of wit, humor and creativity can be difficult to determine. For these reasons, it was decided for the purposes of comparison to subsume the two types under a single heading.

Although combination transliterations are theoretically possible in English, they seem to occur comparatively infrequently. One exception is the relatively recent neologism tsunami wave. The loanword tsunami is the Romanized rendering of the Japanese 津波 tsunami (harbor-wave ‘tsunami; tidal wave’). Thus, while the loanword tsunami is an example of a pure transliteration, the expression tsunami wave could be classified as a transliteration plus explanation, or a combination transliteration. No examples in English of combination transliterations of the form transliteration + translation have as yet come to light in the literature reviewed thus far.

Graphic loans, in which a form-pronunciation combination is borrowed without the associated meaning, do not seem to occur in everyday English language use. In specialized fields such as mathematics, physics and chemistry, however, it is possible to find loans of this type. The constant π is a case in point. The ancient Greek letter has been borrowed together with an approximation of its original pronunciation, but it has been given a new semantic designation, namely the value of the mathematical constant (approximately 3.14159). Although the use of such loans in English seems to be limited to certain fields, it is interesting to note that, at least in principle, this type of borrowing is possible in English.

The wholesale borrowing of initialisms and acronyms from other languages does not seem to be a popular strategy amongst English speakers. In fact, no examples of these types in English have come to light in the literature reviewed.

The construction of hybrids seems to be a peculiarly Chinese phenomenon. Without subjecting this class of neologisms to more fine-grained analysis, it is difficult to state with any degree of certainty what type of language might be likely to exhibit this kind of borrowing and under what conditions. What is clear, however, is that the existence of this class of neologisms in Modern Standard Chinese is yet another proof of the fact that the Chinese writing system is no longer restricted to the “standard” elements of characters only.

From this brief comparison, it can be seen that although English is generally considered to be flexible, adaptable, and open to language change generally and the influences of language contact more specifically, Modern Standard Chinese is apparently even more so. It might be interesting to consider why this should be the case and what factors (linguistic, social, historic, political, cultural, etc.) might have contributed to this situation.

One reason for the prevalence of calques and phono-semantic matches might be that, as they are written with Chinese characters and tend to obey the same grammatical principles of compounding as autochthonous compounds, they are hard to recognize as loans and may thus be more readily accepted and adopted by native speakers. Another factor that has undoubtedly played a role in recent language change is the fact (mentioned above) that Chinese citizens who commenced school after the mid-1970s have had to learn the pinyin Romanization system from a very early age and are thus all familiar with the Latin alphabet and the names of the letters, which has probably facilitated the adoption of so-called “lettered words,” especially phonetic representations, initialisms, and some hybrids. The popularity of wholesale borrowed words and their widespread use throughout the speech community is harder to explain. This phenomenon can be partly explained as a logical progression under conditions of increasingly extensive and intensive language contact after borrowing relatively large numbers of initialisms and acronyms (refer also to the discussion on the progressive borrowing of wholesale loans in 3.1.2 above). On the other hand, the popularity of such expressions is undoubtedly assisted by sociolinguistic factors such as the use of technical jargon, social prestige, pressures of globalization, etc. (Cook 2014; Guo and Zhou 郭鸿杰,周国强 2003; Jin 金其斌 2005; Wang et al. 王辉等 2004). Such factors are particularly obvious in the case of wholesale borrowed words with an existing and perfectly adequate autochthonous equivalent in common usage (e.g., fire ≡ 开除 kāichú).

It was pointed out early in the discussion of language examples that Modern Standard Chinese speakers are keen on puns and wordplays. This is demonstrated in a number of strategies for borrowing words, including phono-semantic matches and graphic puns, as well as in some strategies for coining new words, for example, the category of so-called “humorous homophones” (Cook 2014). Of course, one reason native speakers of Modern Standard Chinese make such widespread use of puns is that with a closed syllabary of only 400-odd distinct syllables (ignoring tonal differences), there are quite simply many more homophones than in a language like, say, English, with its more than 8000 distinct syllables. In fact, the use of wordplays is deeply embedded in Chinese culture, with many celebrations and superstitions revolving around homophonous expressions; indeed, even political protests have been known to make use of puns.Footnote 33

4 Discussion and conclusions

Based on the findings and analysis presented in the previous section, a number of conclusions can be reached. The ensuing discussion will focus on three different areas, commenting first on issues relating to the taxonomy of language change, then on matters relating to language and dialect contact, before drawing all these observations together to make some remarks on orthographic trends and even venture a few tentative predictions regarding the possible implications of these.

4.1 Taxonomy of borrowing

By undertaking a detailed, fine-grained analysis of the various processes by which neologisms come into being and by suggesting appropriate terminology for classes of borrowing not previously defined (or not defined clearly), this study has shown that Modern Standard Chinese speakers employ a wide range of strategies to expand the lexicon of their language. This fact had previously been overlooked owing to the lack of a detailed break-down of different types of lexical borrowing. In particular, the use of the superficial term zimuci “lettered words” or “alphabetic words” has for decades muddied the waters by obscuring the range of borrowing and coining strategies used within the large and heterogeneous group to which it refers, comprising as it does a number of different classes of neologisms, encompassing both borrowed words and coinages. A remarkable common aspect of many strategies studied in this investigation was the widespread use of and/or reference to homophones, often to comic effect, revealing Chinese speakers’ love of puns and wordplays. Less common but equally fascinating was their demonstrated propensity to ridicule their own (or perhaps other speakers’) non-standard pronunciation of both Modern Standard Chinese and English, as demonstrated in the graphic pun FBI and the hybrid 3Q, respectively.

The comparative analysis of lexical change in Modern Standard Chinese and English undertaken in the present paper yielded some interesting insights. As regards the strategies for borrowing, Chinese speakers demonstrated much greater flexibility and creativity than English speakers both in the number of classes of neologisms and, one suspects, in the overall number of words borrowed in recent decades. With respect to the number of words borrowed, it is perhaps not surprising that Chinese outshines English, as it is well-known that numerous languages around the globe currently find themselves in a developmental stage characterized by copious lexical borrowing from more prestigious language varieties, in particular English. Moreover, it is surely true to say that no nation exerts such significant social and cultural influence over the major English-speaking countries as the Anglo-American and Japanese cultures do in China today. And it is, of course, English and Japanese which have provided the models for the overwhelming majority of words borrowed into Chinese over the last three decades. Nevertheless, it is perhaps surprising that English, which has enjoyed a long and distinguished career as an enthusiastic borrowing language, has apparently not managed to take advantage of nearly the same range of borrowing strategies as Modern Standard Chinese. Overall, this research highlights the flexibility and creativity of Modern Standard Chinese speakers and their playful approach to language use.

4.2 Contact-induced change

Contact-induced lexical change has been the subject of much discussion in the Chinese-language literature. Numerous publications mention the influence of Gang-Tai (‘Hong Kong and Taiwan’) language use on language use in mainland China, while another large cohort engages in heated debate regarding the desirability or otherwise of absorbing increasing numbers of English loanwords into the lexicon of Modern Standard Chinese.