Abstract

Background

High red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is associated with worse outcome in diverse scenarios, including in critical illness. The Sabadell score (SS) predicts in-hospital survival after ICU discharge. We aimed to determine RDW’s association with survival after ICU discharge and whether RDW can improve the accuracy of the SS.

Design

Retrospective cohort study. Setting: general ICU at a university hospital.

Patients

We included all patients discharged to wards from January 2010 to October 2016.

Methods

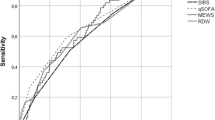

We analyzed associations between RDW and variables recorded on admission (age, comorbidities, severity score), during the ICU stay (treatments, complications, length of stay (LOS)), and at ICU discharge (SS). The primary outcome was hospital mortality. Statistical analysis included multivariable logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analyses.

Results

We discharged 3366 patients to wards; median ward LOS was 7 [4–13] days; ward mortality was 5.2%. Mean RDW at ICU discharge was 15.4 ± 2.5%. Ward mortality was higher at each quartile of RDW (0.7%, 2.9%, 7.5%, 10.3%; area under ROC 0.81). A logistic regression model with Sabadell score obtained an excellent accuracy for ward mortality (area under ROC 0.863), and the addition of RDW slightly improved accuracy (AUROC 0.890, p < 0.05). Recursive partitioning demonstrated higher mortality in patients with high RDW at each SS level (1.6% vs. 0.3% in SS0, 9.7% vs. 1.1% in SS1, 21.9% vs. 9.7% in SS2), but not in SS3.

Conclusion

High RDW is a marker of severity at ICU discharge and improves the accuracy of Sabadell score in predicting ward mortality except in the more extreme SS3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The primary mission of intensive care units (ICU) is to improve the survival of critically ill patients. The first severity scores to predict mortality in patients admitted to the ICU were based on the maximum deviations of physiological variables. These scores have been periodically refined by including new variables or by adjusting the weight of each variable. In the most recent versions, the weight of physiological variables has decreased while the weight of patients’ comorbidities and health status has increased [1].

One physiological variable with the potential to improve the accuracy of severity and prognostic scores is red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Simple and inexpensive to obtain, RDW reflects the degree of heterogeneity of erythrocyte volume (anisocytosis); RDW has traditionally been used in the differential diagnosis of anemias. An increased RDW mirrors a profound deregulation of erythrocyte homeostasis involving both impaired erythropoiesis and abnormal red blood cell survival, which may be attributed to a variety of underlying metabolic abnormalities such as shortening of telomere length, oxidative stress, inflammation, poor nutritional status, dyslipidemia, hypertension, erythrocyte fragmentation, and alteration of erythropoietin function [2]. Many clinical conditions are associated with RDW above the upper limit, commonly accepted as 14.5%. Some of these conditions are inflammatory, others are hematological, and others are comorbidities (e.g., obesity, aging, smoking) [2]. High RDW has been associated with worse outcome in various conditions, such as community-acquired pneumonia [3, 4], myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest [5], and cerebral infarction [6], and in very different scenarios (e.g., critically ill patients on admission [7,8,9], during the ICU stay [10, 11], and long-term after hospital discharge [12]). Nevertheless, adding high RDW failed to improve the accuracy of common severity scores [13], suggesting that factors associated with high RDW (e.g., fever, leukocytosis, or cancer) may already be included in severity scores.

Our group investigates outcomes of patients in the ward after ICU discharge; this research led to the Sabadell score in 2006 [14]. A multicenter validation study confirmed that the Sabadell score classifies patients into four groups with very different ward mortality [15]. A trial is underway to elucidate whether intensivist surveillance can improve ward survival in different Sabadell score groups [16]. The real value of studying this population is that ICU surveillance after discharge is a growing wave, but needs to clearly frame those patients with a higher likelihood for complications and mortality. The follow-up of the entire ICU-discharged population is not worthy and unrealistic. Outreach teams need sensitive markers to identify ward patients at risk, and biomarkers like RDW are promising candidates [17, 18].

We aimed to determine the association of RDW with ward survival after ICU discharge and whether RDW can improve the accuracy of the Sabadell score. We hypothesized that adding RDW would improve the accuracy of the Sabadell score for predicting ward mortality after ICU discharge.

Methods

We retrospectively studied all patients registered in our computerized database between January 2010 and October 2016; accordingly, informed consent was waived.

Our 16-bed mixed ICU admits patients with all kinds of medical and surgical conditions except those who have undergone cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, or transplantation and also serves as a coronary unit and stroke unit for a population of 200,000 inhabitants.

We excluded patients who died during the ICU stay and those who were not discharged to the ward, mainly due to transfer to other hospitals or nursing homes or direct discharge to their homes. Patients needing ICU readmission during the index hospitalization were not included twice; their outcomes were attributed to their first ICU admission.

On ICU admission, we recorded age, sex, diagnosis, SAPS3 score, and comorbidities. During the ICU stay, we recorded major ICU procedures (mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, vasoactive drugs, tracheostomy, and blood transfusion) and adverse events (nosocomial pneumonia, acute renal failure, and delirium). At discharge from the ICU (or step-down unit, when applicable), the attending physician classified the patient according to the Sabadell score, a subjective tool explained in detail elsewhere [14]. Briefly, it has four levels of expected prognosis based on the clinician perception taking into account the illness evolution, comorbidities, sequelae, and socio-familiar support: score 0 is for patients with good prognosis, score 1 is for patients with poor prognosis in the medium-to-long term and acceptable ICU readmission, score 2 is for patients with poor prognosis in the short-term and debatable ICU readmission, and score 3 is for patients who are expected to die before discharge from the hospital.

Routine laboratory reports of blood work ordered by attending physicians as clinically required always included RDW. Based on previous references (4, 9, 10), high RDW was defined as greater than 14.5%. For the purpose of the present study, we used the last RDW recorded before discharge to the ward.

Variables are reported as means ± standard deviations, medians [interquartile ranges], or percentages and odds ratios, as appropriate. We used t tests to compare the means of continuous normal variables, Mann-Whitney U tests to compare the medians of continuous non-normal variables, and Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables; significance was set at p < 0.5.

Variables at ICU admission, during ICU stay, and at ICU discharge were compared between patients with and without high RDW values. Variables that were significant in the univariable analyses were included in a multivariable logistic regression analysis with ward mortality as the dependent (outcome) variable. The discrimination of the multivariate model was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). Accuracy was considered to be good if the area under the curve was more than 0.75 and excellent if more than 0.85. To evaluate the contribution of high RDW to the prognostic value, we calculated the increase in the AUROC of the logistic model after including high RDW. Areas under the ROC curves (AUC) from logistic models were compared with Stata’s “roccomp” command (chi-squared test).

Results

In the 6-year study period, we admitted 4675 patients to our ICU. Of these, 621 (13.3%) died during the ICU stay, 349 (7.5%) were directly discharged home, 329 (7.0%) were transferred to other hospitals or nursing homes, 10 (0.2%) were lost, and 3366 (72.0%) were discharged to the ward. The median length of ward stay was 7 [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] days, and 177 (5.3%) patients died in the wards.

Table 1 compares the recorded variables in patients with high RDW versus patients without high RDW. All the variables recorded at ICU admission (age, cancer, hepatic cirrhosis, and SAPS3 mortality risk), during ICU stay (blood transfusion, delirium, vasoactive drugs, mechanical ventilation, and acute renal failure), and at ICU discharge (ICU length of stay and Sabadell score) were worse in patients with high RDW, suggesting a profile of sicker patients.

After ICU discharge, patients with high RDW had longer ward stay (9 [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] vs. 6 [4–10.5] days; p < 0.001) and higher ward mortality (154 (8.4%) vs. 22 (1.4%); p < 0.001), as depicted in Fig. 1. For ward mortality, high RDW showed a sensitivity of 0.87 (0.81–0.92), specificity of 0.471 (0.468–0.474), positive predictive value of 0.084 (0.078–0.088), and negative predictive value 0.986 (0.979–0.991). A closer look at RDW and ward mortality demonstrated a stepwise correlation between RDW and ward mortality (Table 2). Partitioning the total population in quartiles of RDW, ward mortality ranged from 0.7% for RDW < 13.8% to 10.3% for RDW > 16.1%. The SAPS3 score was progressively worse at each quartile, and the standardized mortality ratio was also worse at higher quartiles of RDW (Table 2).

Variables associated with ward mortality in the univariable analysis were age, cancer, SAPS3, delirium, acute renal failure, blood transfusion, vasoactive drugs, mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, Sabadell score, and high RDW (Table 3).

Sabadell score for prediction of ward mortality showed an AUROC of 0.863, and the inclusion of high RDW improved the AUROC to 0.890 (p < 0.05).

The best multivariable logistic regression model, which included age, SAPS3, and Sabadell score, yielded an AUROC of 0.901, with good calibration (Lemeshow goodness-of-fit = 0.118). Moreover, the addition of RDW slightly improved the accuracy of the model only marginally (AUROC 0.908; p = 0.047).

Additionally, when patients were grouped according to Sabadell score, high RDW identified patients with significantly higher ward mortality (Fig. 2). High RDW was significantly associated with higher ward mortality in patients with Sabadell score 0 (1.6% vs. 0.3%, OR 5.0 [1.6–17.8]), Sabadell score 1 (9.7% vs. 1.1%, OR 9.3 [2.1–53.2]), and Sabadell score 2 (21.9% vs. 9.7%, OR 2.6 [1.0–7.2]), but not in Sabadell score 3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that high RDW is a marker of severity in patients discharged from the ICU to the wards. Additionally, high RDW identified patients with higher ward mortality at each level of prognosis depicted by the Sabadell score, except the most extreme SS3.

Our results in a wide sample of critically ill patients are in line with previous reports demonstrating high RDW as a marker of severity. Sadaka et al. [7] retrospectively studied 279 patients with septic shock and demonstrated that each quintile of RDW increase was associated with higher ICU mortality. Meynaar et al. [8] retrospectively studied 2915 patients in a mixed ICU and found that high RDW on admission was associated with hospital mortality; in multivariate analysis, RDW remained an independent risk factor for mortality after correction for APACHE II score, age, admission type, and mechanical ventilation (odds ratio 1.04 for each femtoliter of RDW). Bazick et al. [9] retrospectively studied a wide population of ICU patients and found that each quintile of RDW increase was associated with increased mortality and with an increased risk of acquiring a bloodstream infection. Zhang et al. [11] retrospectively studied 1539 ICU patients and found that high RDW on admission was associated with mortality, but its predictive performance was suboptimal (AUROC 0.62). Last year, Otero et al. [19] studied 500 critically ill surgical patients; 47% had high RDW on admission, and high RDW was associated with a twofold increase in mortality. In our study, ward mortality increased with RDW at ICU discharge. Beyond what would be expected considering the association between high RDW and severity of illness as defined by the SAPS3 score, the standardized mortality ratio was worse at higher RDW levels (Table 2).

The dynamic nature of RDW precludes firmly establishing the best time for RDW determination. Kim et al. [10] prospectively studied 329 septic patients and found that an increase in RDW > 0.2% from baseline during the first 72 h after hospitalization was significantly associated with higher mortality, even after adjusting for SOFA score and other covariates. Nevertheless, other investigators found no differences attributable to the evolution of RDW during the ICU stay [11]. We analyzed RDW at ICU discharge rather than at ICU admission, with the aim of attaining a better picture of the at-risk population just before discharge to the ward. To our knowledge, no other studies have focused on RDW at ICU discharge, although Purtle et al. [12] concluded that high RDW at hospital discharge is a robust predictor of subsequent all-cause patient mortality in critical care patients that survive hospitalization.

Another issue is whether high RDW can improve current mortality prediction models. In specific subgroups, some investigators [7, 20] found that adding high RDW resulted in statistically significant improvements in the predictive performance of severity scores, but that these increases were of little practical usefulness. In septic patients, Sadaka et al. [7] found that adding high RDW increased the AUROC from 0.69 to 0.77 in APACHE II. In patients treated with continuous renal replacement, Oh et al. [21] found that adding high RDW to SOFA increased the AUROC from 0.69 to 0.75. However, other investigators found that adding high RDW brought about only marginal improvement in APACHE II [8] and APACHE III [13]. In our study, adding high RDW improved the predictive performance of SAPS3 risk of death only marginally (AUC 0.778 vs. 0.798, data not shown).

Ward survival after ICU discharge remains an unresolved issue. In some scenarios, it appears to be a quality indicator, with higher mortality suggesting suboptimal treatment in the ward or premature ICU discharge. Nevertheless, some patients who survive the ICU stay have severe derangements that preclude significant recovery, and ward physicians and outreach teams would benefit from better classification of patients at ICU discharge [17, 18, 22]. A decade ago, Fernandez et al. [14, 15] devised a subjective score that classifies patients at ICU discharge into four groups with very different mortality in the ward, the Sabadell score. In the present study, adding high RDW to the Sabadell score improved the prediction of outcome in patients discharged to the ward. In each Sabadell score group except the worst (patients with null expected survival in the ward), patients with high RDW had substantially higher mortality than those with normal RDW.

Whether or not outreach teams should target patients with high RDW will depend on further investigations about the feasibility of treating the underlying conditions responsible for high RDW (inflammation, underperfusion states, or occult cancer).

Limitations of the study

Our analysis of outcome at hospital discharge did not include patients transferred from the ward to other community hospitals or nursing homes. Nevertheless, in our public system, these transfers account for a minority of patients.

The lack of impact of high RDW in the more extreme SS3 patients may be related either to a small sample size or to the fact that mortality in this specific condition in mostly related to other variables (severe brain damage, refractory heart failure, and decisions to withhold/withdraw life support treatments).

We conclude that high RDW is a marker of severity in patients discharged from the ICU and improves the accuracy of the Sabadell score in predicting ward mortality except in the more extreme SS3. Whether outreach teams should target high patients with RDW remains to be determined.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute physiologic and chronic health evaluation

- AUROC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RDW:

-

Red blood cell distribution width

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operator characteristic

- SAPS3:

-

Severity Acute Physiologic Score

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- SS:

-

Sabadell score

References

Metnitz PG, Moreno RP, Almeida E, et al. SAPS 3--from evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 1: objectives, methods and cohort description. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1336–44.

Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, et al. Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52:86–105.

Lee SM, Lee JH, Kim K, et al. The clinical significance of changes in red blood cell distribution width in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2016;3:139–47.

Ku NS, Kim HW, Oh HJ, et al. Red blood cell distribution width is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with gram-negative bacteremia. Shock. 2012;38:123–7.

Kim J, Kim K, Lee JH, et al. Red blood cell distribution width as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1248–52.

Kim J, Kim YD, Song TJ, et al. Red blood cell distribution width is associated with poor clinical outcome in acute cerebral infarction. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:349–56.

Sadaka F, O'Brien J, Prakash S. Red cell distribution width and outcome in patients with septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28:307–13.

Meynaar IA, Knook AH, Coolen S, et al. Red cell distribution width as predictor for mortality in critically ill patients. Neth J Med. 2013;71:488–93.

Bazick HS, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, et al. Red cell distribution width and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1913–21.

Kim CH, Park JT, Kim EJ, et al. An increase in red blood cell distribution width from baseline predicts mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care. 2013;17:R282.

Zhang Z, Xu X, Ni H, et al. Red cell distribution width is associated with hospital mortality in unselected critically ill patients. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:730–6.

Purtle SW, Moromizato T, McKane CK, et al. The association of red cell distribution width at hospital discharge and out-of-hospital mortality following critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:918–29.

Loveday S, Sinclair L, Badrick T. Does the addition of RDW improve current ICU scoring systems? Clin Biochem. 2015;48:569–74.

Fernandez R, Baigorri F, Navarro G, et al. A modified McCabe score for stratification of patients after intensive care unit discharge: the Sabadell score. Crit Care. 2006;10:R179.

Fernandez R, Serrano JM, Umaran I, et al. Ward mortality after ICU discharge: a multicenter validation of the Sabadell score. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1196–201.

Cano S. To survive after ICU discharge. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02599636. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02599636 (Accessed 24 Apr 2017).

Ranzani OT, Prada LF, Zampieri FG, et al. Failure to reduce C-reactive protein levels more than 25% in the last 24 hours before intensive care unit discharge predicts higher in-hospital mortality: a cohort study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:525.e9–15.

Matsumura Y, Nakada TA, Abe R, et al. Serum procalcitonin level and SOFA score at discharge from the intensive care unit predict post-intensive care unit mortality: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114007.

Otero TM, Canales C, Yeh DD, et al. Elevated red cell distribution width at initiation of critical care is associated with mortality in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2016;34:7–11.

Hunziker S, Celi LA, Lee J, et al. Red cell distribution width improves the simplified acute physiology score for risk prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2012;16:R89.

Oh HJ, Park JT, Kim JK, et al. Red blood cell distribution width is an independent predictor of mortality in acute kidney injury patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:589–94.

Lee H, Lim CW, Hong HP, et al. Efficacy of the APACHE II score at ICU discharge in predicting post-ICU mortality and ICU readmission in critically ill surgical patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43:175–86.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF was responsible for the conception of the study. SC, IC, OR, CS, JM, GR, LV, CM, and JMA were responsible for the acquisition of data. RF and LW were responsible for the analysis of data. RF was responsible for the interpretation of data and for drafting the manuscript. RF, SC, IC, OR, CS, JM, GR, LV, CM, and JMA were responsible for revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Unió Catalana d’Hospitals, and informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandez, R., Cano, S., Catalan, I. et al. High red blood cell distribution width as a marker of hospital mortality after ICU discharge: a cohort study. j intensive care 6, 74 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0343-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0343-3