Abstract

Encrustation and element content (Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P) of charophytes was studied along plant thalli to investigate the dependency of thallus age and site-specificity. Charophytes were collected from five sampling sites (Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche, Bruchwiesen, Krüselinsee and Lützlower See) which were distinct with respect to water chemistry. Furthermore, photosynthesis was measured to identify the physiological state of plants in habitat waters and with the addition of different ion concentrations (Ca2+, K+, Mg2+ and Na+). Age pattern on encrustation of charophytes was site-specific: carbonate content increased from the youngest to the oldest part (Angersdorfer Teiche), younger parts were less encrusted than older parts in Asche, Bruchwiesen and Krüselinsee, whereas encrustation in Lützlower See was the same along plants thallus. Charophytes showed species-specific encrustation in investigated sites. Encrustation of C. hispida in Angersdorfer Teiche was also as high as of individuals from hard-water lakes irrespective of 10.15 mS cm−1 (salinity of 6.3). For species growing in Angersdorfer Teiche, K/Na content and photosynthesis was lowest when compared to other sites. Photosynthesis of charophytes was enhanced after the addition of KCl and adversely affected by CaCl2, MgCl2 and NaCl. In summary, it was shown that encrustation of charophytes in water sites with strong ion anomalies could be as high as in hard-water lakes. It is assumed that ion composition, rather than ion concentration of Na+, Mg2+ and SO42−, impact on the encrustation of charophytes. The age pattern on encrustation in this study showed a strong site-specificity, whereas encrustation of charophytes was species-specific. Ion concentrations, either of habitats or actively added in laboratory measurements, impact on encrustation, element content and photosynthesis of charophytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Charophytes are macrophytes of the order Charales Lindley 1836 belonging to the streptophyta (Jeffrey 1967; Stewart and Mattox 1975). This lineage also includes the embryophyta, thus charophytes are closely related to land plants (Jeffrey 1967; McCourt 1995; Nishiyama et al. 2018). Charophytes can form dense meadows which provide habitats and shelter for epiphytes, invertebrates and fish, indicating their important ecological function in the ecosystem (Kairesalo et al. 1987; Kingsford and Porter 1994; Kuczyńska-Kippen 2007). The presence or absence of charophytes seems to depend on abiotic lake characteristics; water chemistry especially plays an important role (van den Berg et al. 1998a; Blindow et al. 2014). They often occur in waters with low nutrient concentrations. Therefore, some charophytes can serve as bioindicators for nutrient-poor conditions (Krause 1981; Doege et al. 2016). In clear-water ecosystems charophytes are more competitive than other macrophytes but are outcompeted under eutrophic conditions (Ozimek and Kowalczewski 1984; Pieczyńska et al. 1988; Blindow 1992). However, charophytes are not limited to oligotrophic waters, also inhabiting eutrophic waters when niches are available (van den Berg et al. 1998b; Schubert et al. 2018). In hard-water lakes, charophytes encrust on the plant surface (Wahlstedt 1875; Sand-Jensen et al. 2018). Calcium carbonate content can thereby account for up to 80% of plant dry weight (Pukacz et al. 2016a). In the case of heavy encrustation of charophytes, it has been described that supersaturation with calcium carbonate of the water was not required (Nõges et al. 2003; Kufel et al. 2016). Several authors pointed out the importance of site-specificity, and the influence that depth, temperature, pH, and water chemistry parameters have on the encrustation of charophytes (Kufel et al. 2013, 2016; Pukacz et al. 2016a, b). So far age dependent encrustation was analyzed by Kawahata et al. (2013); younger internodes of C. globularis Thuill. 1799 were less encrusted than older ones. In situ studies on encrustation regarding age and site-specificity have never been done. Therefore, encrustation was analyzed in parts of corticated thallus for C. canescens Loisel. 1810, C. hispida L. 1753, C. subspinosa Rupr. 1846 and C. tomentosa L. 1753 from five areas of water in Germany. We investigated whether carbonate and element (Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P) contents of plant dry weight (DW) are dependent on thallus age and sites sampled. Furthermore, photosynthesis was measured to identify the physiological state of plants in habitat waters and with the addition of different ion concentrations (Ca2+, K+, Mg2+ and Na+).

Materials and methods

Sampling sites

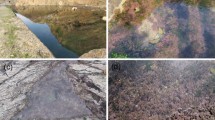

In July 2016 five areas of water were investigated in the northeast and eastern part of Germany (Fig. 1). These included two residual mining holes: Angersdorfer Teiche, a clay pit filled with rain and groundwater, and Asche in Teutschenthal, which is located close to a potassium mining heap, in the lake area Mansfelder region. Bruchwiesen, a natural spring, in Bad Tennstedt was also sampled, as well as two hard-water lakes, Krüselinsee in Mecklenburg Lake District and Lützlower See in Uckermark.

Sampling processing

Plant material was collected at a depth of 0.5–1.5 m from the shore, or by snorkeling. Undamaged plants of C. canescens, C. hispida, C. subspinosa, and C. tomentosa were picked. In the laboratory, epibionts were removed gently with a brush. For further analyses, plants were analyzed in parts of thalli. First to third, forth to sixth, seventh to ninth whorls and internodes were used for analysis (Fig. 2). Side branches and other parts of thalli were removed.

Comparison of carbonate content based on DW (%) of C. canescens (can), C. hispida (his), C. subspinosa (sub), and C. tomentosa (tom) from sampling sites (Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche, Bruchwiesen, Krüselinsee, and Lützlower See). Plants were analyzed in first to third (white), forth to sixth (light grey), seventh to ninth (dark grey boxplots) whorls and internodes. Box plots include whiskers (5–95% of variability) and outliers (points). Different letters indicate significant difference within the same sampling site (Tukey HSD post hoc test, p < 0.05)

Carbonate proportion of plant dry weight was determined by the loss of ignition (LOI) method as described by Heiri et al. 2001. Sample size was n = 7 for the LOI analysis. The samples were dried at 60 °C (UM 400, Memmert) overnight. Plant DW was weighed and combusted in crucibles in a two-step process, at 550 °C (DW550) and 925 °C (DW925) for two hours, respectively (LE 6/11/B 150, Nabertherm). Carbonate content of DW (%) was calculated of the carbonate bounded CO2 loss multiplied by 1.36 (fraction of CO2 in CO32−) after Pełechaty et al. 2013 (Eq. 1).

Element contents of Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P were measured with inductively coupled plasma-optic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Plant DW was ground and 0.1 g was weighted for the digestion. Samples were extracted in duplicate with 5 ml HNO3 (65%) and 3 ml H2O2 (30%) for 1.5 h in CEM MARS 6 microwave. After extraction, samples were filled up to 25 ml with ultrapure water and were filtered (601P, Rotilabo). Samples were analyzed spectrometrically for Ca (317.9 nm), Fe (238.2 nm), K (766.5 nm), Mg (285.2 nm) and P (214.9 nm) with Optima 8300 (Perkin Elmer, Singapore).

Photosynthesis of C. canescens, C. hispida from Angersdorfer Teiche, C. hispida from Asche, and C. tomentosa from Bruchwiesen was measured by means of O2 evolution with a Clark-type electrode (Microelectrodes, USA). Within a day after sampling, plants were dark adapted at least for 30 min and were set in a temperature-controlled 2.5 ml cuvette (15 °C). The cuvette was filled with habitat medium which was stirred during measurement. Photon flux densities were applied by a light dispenser system (MK2, Illuminova, Sweden) described by Wolfstein and Hartig (1998). Dark respiration was measured for 10 min, followed by increasing irradiation levels of 14, 18, 31, 102, 494, 912, 1462, 1811, 2120 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Each irradiation level was set for 3.3 min; measurement took 40 min in total.

Photosynthesis of C. tomentosa from Asche was measured with the addition of CaCl2, KCl, MgCl2 and NaCl. Plants were cultivated in habitat water and at a constant temperature (15 °C) and light (50–80 µmol photons m−2 s−1 on a 12 h/12 h light–dark cycle) to allow consistent conditions for measurements. Light saturation irradiance (Is) of cultivated C. tomentosa was calculated in preliminary measurements (Is = 120 µmol m−2 s−1). For 20 min measurements, 1.5 × Is (1.5Is = 180 µmol m−2 s−1) was used to gain light saturation. After a dark period of 3 min, constant irradiance level of 180 µmol m−2 s−1 was set. Concentration of 1.2 mmol L−1 of chloride salt was added at minutes 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, and 17 of measurement. The end concentration was 8.4 mmol L−1 added chloride salt in the cuvette. Control measurements were conducted without addition of chloride salt.

Photosynthesis/irradiance (P/I) curve was calculated using the model of Walsby (1997) to determine photosynthesis (P), maximum photosynthesis (Pm), dark respiration (Rd), α (slope of P/I curve at limiting irradiance), light compensation point (Ic = Rd/α), and light saturation irradiance (Is = Pm/α). Photosynthetic parameters were based on chlorophyll a (chl a). Pigment content of first to third whorls and internodes were extracted with 3 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide. Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Extinction at 470, 630, 647, 664, and 750 nm was measured using a Lambda 2 spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Germany). Chl a content was calculated after Wellburn (1994).

Water samples were taken in 50 ml tubes above plant meadows, closely beneath the water surface. pH value and conductivity were measured directly at sampling sites with HACH HQ40d (Hach-Lange, Germany). The water samples were analyzed at Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ)—Central Laboratory for Water Analytics and Chemometrics. The concentrations of Ca2+, Cl−, K+, Mg2+, Na+, and SO42− were measured with an ion chromatograph (Dionex ICS 3000, Thermo Fisher, USA). Total inorganic carbon (TIC) was determined with a Dimatoc 2000 (DIMATEC, Germany). Water samples were measured in accordance with EN ISO 14911:1999 and EN ISO 10304:2009-1.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed for normality and homogeneity. In cases of normal and homogeneous distribution, data were analyzed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Tukey HSD test. For no normal distributed data, a non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis test and Fisher Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test) with Bonferroni correction for p-values adjustment was performed (de Mendiburu 2016). A principal component analysis (PCA) based on standardized data of element contents of Ca, Fe, K, Mg and TP of plant DW was conducted (Oksanen et al. 2017). Significance levels were set to a p-value ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R Core Team 2017).

Results

Water chemistry

Water chemistry data of investigated sites are listed in Table 1. The sampling sites were distinct with respect to water chemistry, exhibiting enhanced ion concentrations in Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche, and Bruchwiesen. The highest ion concentrations of Ca2+, Cl−, K+, Na+ and SO42− were found in the gips pit Angersdorfer Teiche. Mg2+ was an exception and the highest concentration was obtained in Asche. Bruchwiesen had high Ca2+ and SO42− concentrations compared to Krüselinsee and Lützlower See. Both hard-water lakes had the lowest conductivity of investigated waters. Total inorganic carbon (TIC) concentration was highest in Bruchwiesen and lowest in Angersdorfer Teiche. pH was around 9 in Angersdorfer Teiche, Krüselinsee and Lützlower See, 7.9 in Asche, and lowest in Bruchwiesen with 7.4.

Encrustation

Encrustation was analyzed in parts of plant thalli (Fig. 2). A pattern of lowest carbonate content in the first to third, middle in the forth to sixth, and highest in the seventh to ninth whorls and internodes was found for both species (C. canescens and C. hispida) from Angersdorfer Teiche (Fisher LSD post hoc test, p < 0.01). In Asche, Bruchwiesen, and Krüselinsee, the younger parts of C. hispida, C. subspinosa, and C. tomentosa were less encrusted than the middle and older parts of the plant thalli (Fisher LSD post hoc test, p < 0.001). In Lützlower See, C. subspinosa and C. tomentosa exhibited no significant differences in encrustation between their respective parts of the thalli.

Furthermore, encrustation was species-specific for species in Angersdorfer Teiche. C. hispida encrusted higher than C. canescens. Site-specific encrustation was found for C. hispida growing in Angersdorfer Teiche and Bruchwiesen with a lower carbonate proportion of C. hispida in Bruchwiesen (Fisher LSD post hoc test, p < 0.01). Also C. tomentosa encrustation was site-specific in Asche compared to individuals from Krüselinsee and Lützlower See. Encrustation of C. tomentosa was lower in Asche than in Krüselinsee and Lützlower See (Fisher LSD post hoc test, p < 0.001).

Element composition

Element content based on plant dry weight was analyzed for species from habitats with high ion concentrations (Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche, and Bruchwiesen) to investigate the impact thereof (Fig. 3 and Table 2). In the PCA plot, C. hispida from Bruchwiesen was separated from the species of Angersdorfer Teiche and Asche. Habitat differences were pronounced by means of lowest contents of Mg and Na in C. hispida from Bruchwiesen (Table 2). Further, parts of the thallus were ordered along the axis 1 which was characterized most by Ca, P, and Na contents.

Regarding the element content, Ca was lowest in C. canescens and highest in C. hispida, both from Angersdorfer Teiche. K content was significantly higher in C. canescens compared to C. hispida (Angersdorfer Teiche) and C. tomentosa (Asche). Na content was different for all species investigated; highest in C. canescens (Angersdorfer Teiche) and lowest in C. hispida (Bruchwiesen). The ratio of K/Na was low (< 1) for both species from Angersdorfer Teiche and highest in C. hispida from Bruchwiesen. P content was significantly higher in C. canescens compared to C. hispida (Angersdorfer Teiche) and C. tomentosa (Asche).

Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis was measured in plants from Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche and Bruchwiesen (Table 3). Pm of C. canescens (33.8 ± 9.6 1 mmol O2 h−1g chl a−1) and C. hispida (42.1 ± 6.1 mmol O2 h−1 g chl a−1) from Angerdorfer Teiche were not significantly different to C. tomentosa from Asche (64.3 ± 20.2 mmol O2 h−1 g chl a−1) and C. hispida from Bruchwiesen (64.7 ± 18.8 mmol O2 h−1 g chl a−1). α, Rd and Is were also similar for species measured. Significant difference was found for the light compensation point; C. canescens from Angersdorfer Teiche had significantly lower Ic than C. hispida from Bruchwiesen.

Photosynthesis of C. tomentosa from Asche was measured with the addition of CaCl2, KCl, MgCl2, NaCl and without any addition, as a control (Table 4). Differences in O2 evolution was found with addition of CaCl2, KCl and MgCl2, NaCl at concentrations of 2.4, 3.6, 4.8 and 6.0 mmol L−1. O2 evolution of C. tomentosa was higher with the addition of KCl and CaCl2 compared to MgCl2 and NaCl. At 8.4 mmol L−1 O2 evolution of C. tomentosa was lowest with the addition of NaCl.

Discussion

Encrustation was studied in brackish waters with strong ion anomalies. Increased ion concentrations were found in Angersdorfer Teiche, Asche and Bruchwiesen. For comparison, samples were also taken in two hard-waters lakes; Krüselinsee and Lützlower See. Carbonate precipitation was highest for charophytes in hard-water lakes and of C. hispida in Angersdorfer Teiche. This was not expected for C. hispida growing in Angersdorfer Teiche at a salinity of 6.3. Herbst et al. (2018) quantified encrustation of charophytes from freshwater and brackish water sites. Freshwater specimens had higher carbonate content of DW compared to brackish water specimens (Herbst et al. 2018). Thus, ion composition rather than ion concentration, is decisive for encrustation of charophytes. It could further explain the low carbonate precipitation of C. tomentosa in Asche, where Mg2+ exceeded Ca2+ concentrations, and consequently inhibits the encrustation as described by other authors (Siong and Asaeda 2009; Gomes and Asaeda 2010; Asaeda et al. 2014). Additionally, high SO42− concentrations in Asche and Bruchwiesen could reduce the encrustation of charophytes as Akin and Lagerwerff (1965) reported increased solubility of calcium carbonate at high SO42− concentrations.

The results emphasize the importance of water ion composition on carbonate precipitation of charophytes, which was strengthened regarding the site-specific pattern on encrustation along the age gradient of the plants. Here ‘age’ referred to the cell age along the plant thallus at a certain state. Site-specific patterns of encrustation were found: all parts of plant thalli (youngest, middle, and oldest) were different; the youngest differed from the other parts, and encrustation was similar for all parts of the thalli. Kawahata et al. (2013) confirmed age dependent encrustation along internodes of C. globularis. Younger internodes were less encrusted than older ones (Kawahata et al. 2013). Carbonate formations were also detected between the cortex and cell wall which indicated that encrustation was enclosed during forming of the cortex (Kawahata et al. 2013). Three levels of carbonate formation can therefore be distinguished; external precipitation, which can occur outside as well as intra-thallose and internal calcification of oospores which are termed gyrogonites (Raven et al. 1986; Leitch 1991; Kawahata et al. 2013).

The age pattern on encrustation in this study showed a strong site-specificity which probably arise by combination of the plant growth rate and carbonate formation rate. In both hard-water lakes, Lützlower See and Krüselinsee, age pattern on encrustation differed. The youngest parts of C. subspinosa and C. tomentosa showed less encrustation than other parts in Krüselinsee compared to individuals from Lützlower See. In Lützlower See, encrustation was similar along plant thalli. Slow growth rate and fast encrustation rate, due to higher Ca2+ concentration in Lützlower See, are likely to produce uniform encrustation of the whole plant.

However, in Bruchwiesen and Asche the youngest parts of plant thalli were also less encrusted than other parts, even under extreme high Ca2+ concentrations. Both study sites were also influenced by high concentrations of Mg2+ and SO42−, which could adversely affect the carbonate formation rate. Furthermore, in the spring Bruchwiesen, temperatures did not exceed 12 °C in summer when sampling took place. Temperature, as another influencing factor, was shown to influence the precipitation of calcium carbonate (Ogata et al. 2010). Further investigations about habitat influence on encrustation of charophytes are needed to elucidate the interaction of various factors.

In Angersdorfer Teiche, the most pronounced difference in encrustation between species (C. hispida and C. canescens) and cell age (youngest, middle, and oldest part) was detected. The strong difference in species-specific encrustation could be explained by its low K/Na contents, which was 0.8 for C. canescens and 0.6 for C. hispida (Table 2). Winter and Kirst (1990) reported reduced vitality of charophytes at a ratio of K+/Na+ < 1, but found also ratios of 0.8–0.9 in Tolypella glomerata Leonh. 1863 and T. nidifica Braun 1856 (Winter et al. 1996) when exposed to a salinity of 12. Both C. hispida, as well as C. canescens, were probably growing close to their physiological limits in Angersdorfer Teiche. Photosynthesis, as a measure of the physiological state, confirmed lower Pm in plants (C. canescens and C. hispida) from Angersdorfer Teiche compared to those from Asche (C. tomentosa) and Bruchwiesen (C. hispida).

It is known that CO2 uptake for photosynthesis is connected to encrustation of charophytes (McConnaughey and Falk 1991; Raven and Beardall 2016). H+ pumping acidified the plant surface and increases CO2 concentration in the surrounding water which permeates into the cells (Beilby and Bisson 2012). The import of CO2 into the chloroplast generates OH− which is excreted by the cell through OH− channels (Beilby and Bisson 2012; Absolonova et al. 2018). Alkaline zones are formed on the plant surface where carbonate is precipitated. Beside lower photosynthesis of plants from Angersdorfer Teiche, concentration of total inorganic carbon was also lowest of investigated sites. The results imply that carbonate uptake for photosynthesis is not the only mechanism responsible for encrustation of charophytes. H+ is also generated by active ion transport which is linked to nutrient uptake and ion regulation (McConnaughey and Whelan 1997; Beilby and Casanova 2014). Consequently, ion regulation and osmoregulation capabilities will interfere with photosynthetic CO2 recruitment and it can be argued, that the low encrustation values exhibited by C. canescens, the only brackish water species in this study, are caused by its different osmoregulation mechanism (Winter and Kirst 1991).

Photosynthesis was affected by the addition of CaCl2, KCl, MgCl2 and NaCl. Addition of CaCl2, MgCl2 and NaCl inhibited photosynthesis; NaCl had the most adverse effect. Na+ toxicity is well-known; an exception is cyanobacteria which require Na+ for the activity of nitrogenase (Thomas and Apte 1984). Furthermore, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ could not balance the effect of Cl−, whereas K+ compensated it. Addition of KCl enhanced photosynthesis when compared to the control measurements. It reflects the importance of ions concentration in habitats for charophyte growth.

Conclusion

In summary, it was shown that encrustation of charophytes in water sites with strong ion anomalies could be as high as in hard-water lakes. It is assumed that ion composition, rather than ion concentration of Na+, Mg2+ and SO42−, impact on the encrustation of charophytes. The age pattern on encrustation in this study showed a strong site-specificity, whereas encrustation of charophytes was species-specific. Encrustation, element composition and photosynthesis of charophytes were influenced by ion concentrations.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- can:

-

C. canescens

- DW:

-

dry weight

- his:

-

C. hispida

- I:

-

irradiance

- Ic :

-

light compensation point

- Is :

-

light saturation irradiance

- LOI:

-

loss of ignition

- P:

-

photosynthesis

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- Pm :

-

maximum photosynthesis

- Rd :

-

dark respiration

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- sub:

-

C. subspinosa

- TIC:

-

total inorganic carbon

- tom:

-

C. tomentosa

References

Absolonova M, Beilby MJ, Sommer A, Hoepflinger MC, Foissner I (2018) Surface pH changes suggest a role for H+/OH− channels in salinity response of Chara australis. Protoplasma 255:851–862

Akin GW, Lagerwerff JV (1965) Calcium carbonate equilibria in aqueous solutions open to the air. I. The solubility of calcite in relation to ionic strength. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 29:343–352

Asaeda T, Senavirathna MDHJ, Kaneko Y, Rashid MH (2014) Effect of calcium and magnesium on the growth and calcite encrustation of Chara fibrosa. Aquat Bot 113:100–106

Beilby MJ, Bisson MA (2012) pH banding in charophyte algae. In: Volkov A (ed) Plant electrophysiology, methods and cell electrophysiology. Springer, Berlin, pp 247–271

Beilby MJ, Casanova MT (2014) The physiology of characean cells. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–205

Blindow I (1992) Decline of charophytes during eutrophication: comparison with angiosperms. Freshw Biol 28:9–14

Blindow I, Hargeby A, Hilt S (2014) Facilitation of clear-water conditions in shallow lakes by macrophytes: differences between charophyte and angiosperm dominance. Hydrobiologia 737:99–110

de Mendiburu F (2016) Agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R package version 1.2-4

Doege A, van de Weyer K, Becker R, Schubert H (2016) Bioindikation mit Characeen. In: Characeen AG (ed) Armleuchteralgen—Die Characeen Deutschlands. Springer, Berlin, pp 79–138

Gomes PIA, Asaeda T (2010) Impact of calcium and magnesium on growth and morphological acclimations of Nitella: implications for calcification and nutrient dynamics. Chem Ecol 26:479–491

Heiri O, Lotter AF, Lemcke G (2001) Loss on ignition as a method for estimating organic and carbonate content in sediments: reproducibility and comparability of results. J Paleolimnol 25:101–110

Herbst A, Henningsen L, Schubert H, Blindow I (2018) Encrustations and element composition of charophytes from fresh or brackish water sites—habitat- or species-specific differences? Aquat Bot 148:29–34

Jeffrey C (1967) The origin and differentiation of the archegoniate land plants: a second contribution. Kew Bull 21:335–349

Kairesalo T, Gunnarsson K, St Jónsson G, Jónasson PM (1987) The occurrence and photosynthetic activity of epiphytes on the tips of Nitella opaca Ag. (Charophyceae). Aquat Bot 28:333–340

Kawahata C, Yamamuro M, Shiraiwa Y (2013) Changes in alkaline band formation and calcification of corticated charophyte Chara globularis. SpringerPlus 2:1–6

Kingsford RT, Porter JL (1994) Waterbirds on an adjacent freshwater lake and salt lake in arid Australia. Biol Conserv 69:219–228

Krause W (1981) Characeen als Bioindikatoren für den Gewässerzustand. Limnologica 13:399–418

Kuczyńska-Kippen N (2007) Habitat choice in rotifera communities of three shallow lakes: impact of macrophyte substratum and season. Hydrobiologia 593:27–37

Kufel L, Biardzka E, Strzałek M (2013) Calcium carbonate incrustation and phosphorus fractions in five charophyte species. Aquat Bot 109:54–57

Kufel L, Strzałek M, Biardzka E (2016) Site- and species-specific contribution of charophytes to calcium and phosphorus cycling in lakes. Hydrobiologia 767:185–195

Leitch AR (1991) Calcification of the charophyte oosporangium. In: Riding R (ed) Calcareous algae and stromatolites. Springer, Berlin, pp 204–216

McConnaughey TA, Falk RH (1991) Calcium-proton exchange during algal calcification. Biol Bull 180:185–195

McConnaughey TA, Whelan JF (1997) Calcification generates protons for nutrient and bicarbonate uptake. Earth Sci Rev 42:95–117

McCourt RM (1995) Green algal phylogeny. Trends Ecol Evol 10:159–163

Nishiyama T, Sakayama H, de Vries J et al (2018) The Chara genome: secondary complexity and implications for plant terrestrialization. Cell 174:448–464

Nõges P, Tuvikene L, Feldmann T, Tõnno I, Künnap H, Luup H, Salujõe J, Nõges T (2003) The role of charophytes in increasing water transparency: a case study of two shallow lakes in Estonia. Hydrobiologia 506–509:567–573

Ogata S, Kawasaki S, Hiroyoshi N, Tsunekawa M, Kaneko K (2010) Temperature dependence of calcium carbonate precipitation for biogrout. In: Vrkljan I (ed) Rock Engineering in difficult ground conditions. Taylor & Francis Group, London, pp 339–344

Oksanen J, Guillaume Blanchet F, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H (2017) Vegan: community ecology package. R Pack Ver 2:4

Ozimek T, Kowalczewski A (1984) Long-term changes of the submersed macrophytes in eutrophic Lake Mikołajskie (North Poland). Aqua Bot 19:1–11

Pełechaty M, Pukacz A, Apolinarska K, Pełechata A, Siepak M (2013) The significance of Chara vegetation in the precipitation of lacustrine calcium carbonate. Sedimentology 60:1017–1035

Pieczyńska E, Ozimek T, Rybak JI (1988) Long-term changes in littoral habitats and communities in Lake Mikołajskie (Poland). Int Rev Ges Hydrobiol 73:361–378

Pukacz A, Pełechaty M, Frankowski M (2016a) Depth-dependence and monthly variability of charophyte biomass production: consequences for the precipitation of calcium carbonate in a shallow Chara-lake. Environ Sci Pollut Res 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7420-8

Pukacz A, Pełechaty M, Frankowski M, Pronin E (2016b) Dry weight and calcium carbonate encrustation of two morphologically different Chara species: a comparative study from different lakes. Oceanol Hydrobiol Stud 45:377–387

Raven JA, Beardall J (2016) The ins and outs of CO2. J Exp Bot 67:1–13

Raven JA, Smith FA, Walker NA (1986) Biomineralization in the Charophyceae sensu lato. In: Leadbeater BSC, Riding R (eds) Biomineralization in lower plants and animals. The systematics association. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 125–139

Sand-Jensen K, Jensen RS, Gomes M, Kristensen E, Martinsen KT, Kragh T, Baastrup-Spohr L, Borum J (2018) Photosynthesis and calcification of charophytes. Aquat Bot 149:46–51

Schubert H, Blindow I, Bueno NC, Casanova MT, Pełechaty M, Pukacz A (2018) Ecology of charophytes—permanent pioneers and ecosystem engineers. PiP 5:61–74

Siong K, Asaeda T (2009) Effect of magnesium on charophytes calcification: implications for phosphorus speciation stored in biomass and sediment in Myall Lake (Australia). Hydrobiologia 632:247–259

Stewart KD, Mattox KR (1975) Comparative cytology, evolution and classification of the green algae with some consideration on the origin of other organisms with chlorophylls a and b. Bot Rev 41:104–135

R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org/

Thomas J, Apte SK (1984) Sodium requirement and metabolism in nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. J Biosci 6:771–794

Van den Berg MS, Coops H, Meijer M-L, Scheffer M, Simons J (1998a) Clearwater associated with a dense Chara vegetation in the shallow and turbid Lake Veluwemeer, the Netherlands. In: Jeppesen E, Søndergaard M, Søndergaard M, Kristoffersen K (eds) The structuring role of submerged macrophytes in lakes. Springer, New York, pp 339–352

Van den Berg MS, Scheffer M, Coops H, Simons J (1998b) The role of characean algae in the management of eutrophic shallow lakes. J Phycol 34:750–756

Wahlstedt LJ (1875) Monografi öfver Sveriges och Norges characeer. Boktryckeri-Aktie-Bolaget, Christianstad, Sweden, p 37

Walsby AE (1997) Numerical integration of phytoplankton photosynthesis through time and depth in a water column. New Phytol 136:189–209

Wellburn AR (1994) The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol 144:307–313

Winter U, Kirst GO (1990) Salinity response of a freshwater charophyte, Chara vulgaris. Plant Cell Environ 13:123–134

Winter U, Kirst GO (1991) Partial turgor pressure regulation in Chara canescens and its implications for a generalized hypothesis of salinity response in charophytes. Bot Acta 104:37–46

Winter U, Soulié-Märsche I, Kirst GO (1996) Effects of salinity on turgor pressure and fertility in Tolypella (Characeae). Plant Cell Environ 19:869–879

Wolfstein K, Hartig P (1998) The photosynthetic light dispensation system: application to microphytobenthic primary production measurements. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 166:63–71

Authors’ contributions

AH was involved in the design of this work, the data acquisition, the analysis and the interpretation of data and drafting the article. HS was responsible for the conception, the design and the interpretation of data. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank P. Nowak for assistance in the field, W. von Tümpling (Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research) for the water analysis, B. Balz and E. Heilmann (AUF, University of Rostock) for providing technical support for the biomass analysis and C. Porsche (MNF, University of Rostock) for advice on the statistical treatment of the data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

One of the authors (AH) was supported by “Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt” and “Professorinnenprogramm II of the University of Rostock”, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Herbst, A., Schubert, H. Age and site-specific pattern on encrustation of charophytes. Bot Stud 59, 31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-018-0247-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-018-0247-5