Abstract

In this article, we propose a novel fractional generalization of the three-dimensional differential transform method, namely the ternary-fractional differential transform method, that extends its applicability to encompass initial value problems in the fractal 3D space. Several illustrative applications, including the Schrödinger, wave, Klein–Gordon, telegraph, and Burgers’ models that are fully embedded in the fractal 3D space, are considered to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method compared with other generalized methods in the literature. The obtained solution is expressed in a form of an α̅-fractional power series, with easily computed coefficients, that converges rapidly to its closed-form solution. Moreover, the projection of the solutions into the integer 3D space corresponds with the solutions of the classical copies for these models. This reveals that the suggested technique is effective and accurate for handling many other linear and nonlinear models in the fractal 3D space. Thus, research on this trend is worth tracking.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Over recent years, it has been demonstrated that many physical phenomena can be successfully reformulated by means of non-integer order differential equations due to the inefficiency of the integer-order differential equations in modeling certain issues. For instance, when modeling chaotic thermodynamic systems, it is indispensable to use a non-integer model because the separation of time-scales of classical physics does not work adequately [1]. The non-integer order derivatives are commonly called fractional order derivatives or simply fractional derivatives. To mention a few of the phenomena that can be modeled by fractional derivatives: the electromagnetic transient phenomenon in transmission lines is governed by the fractional diffusion model [2], the damping properties of the viscoelastic material are related to the fractional Kelvin–Voigt model [3], and the interaction of solitons in a collisionless plasma is simulated by the fractional Klein–Gordon model [4].

The fractional derivatives are in nonlocal nature, unlike the integer-order derivatives. Consequently, it is often stated that the physical interpretation of the fractional derivative order α is hard to pin down or does not exist at all. However, many researchers have attempted to attribute physical meanings to fractional derivatives, see, for example, [5, 6]. It has been demonstrated in certain circumstances that the nonlocality feature of the fractional derivatives makes them appropriate for describing the memory and hereditary features of various materials. Thus, the fractional derivative order α can be physically described as an index of memory [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Differential transform method (DTM) is a powerful transformation technique that can be easily applied to (non)linear problems to achieve much more accurate analytical or numerical solutions than the existing ones in the literature. One of the distinguishing features of this method is its capability to reduce the size of computational work. The concept of the one-dimension DTM was introduced for the first time by Zhou [14] in 1986 to solve problems related to engineering models in electric circuit analysis. Posteriorly, Chen and Ho [15] developed this method to solve two-dimensional PDEs. Later, the three-dimensional DTM was introduced by Ayaz [16].

Over the past few years, the DTM has been successfully implemented in the area of partial differential equations of fractional order. Arikoglu and Ozkol [17] proposed an analytical technique, called the fractional differential transform method (FDTM), for solving (non)linear differential equations endowed with one memory index α. Very recently, Jaradat et al. [18, 19] developed this method to address (non)linear differential equations endowed with two memory indices \(\alpha _{1}\) and \(\alpha _{2}\). It is worth mentioning here that some recent advancements in analytical methods can be also found in [20,21,22,23,24]. In this article, we present a novel fractional generalization of the three-dimensional DTM to extend the application of the DTM to (non)linear differential equations endowed with three memory indices \(\alpha _{1}\), \(\alpha _{2}\), and \(\alpha _{3}\). Comparing with the complexity of these equations, the suggested generalization is efficacious and easily applicable. Several examples were carried out to demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed technique.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. We amalgamate the DTM with a new ternary-fractional power series in Sect. 2 to handle physical differential equations in the fractal 3D space. Then, in Sect. 3, we employ the new formulation of DTM to provide a full fractional solution of several well-known physical models in the fractal 3D space. In Sect. 4, we offer a potential interpretation for the fractional derivative order. Finally, we present concluding remarks in Sect. 5.

2 Ternary-fractional differential transform schema

In this section, we introduce and investigate a developed analytical scheme, derived from a novel fractional version of the Taylor series expansion, to handle various (non)linear differential equations in the fractal 3D space. This new technique generalizes the classical three-dimensional differential transform ideas in the fractal 3D space and provides new insights for analytically studying the combined effects of three distinct memory indices. The ternary-fractional power series is defined as follows.

Definition 2.1

([25])

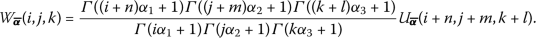

An α̅-fractional power series (α̅-FPS) around \((0,0,0)\) is a fractional power series in the following Cauchy form:

where \(\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}=(\alpha _{1}, \alpha _{2}, \alpha _{3}) \in (0,1)^{3}\), x, y, t are nonnegative variables of indeterminate, and \(a_{i,j,k}\)’s are real constant coefficients.

It is readily verified that expansion (2.1) can be expressed as

Definition 2.2

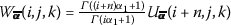

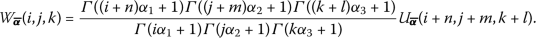

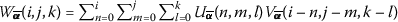

The ternary-fractional differential transform (ternary-FDT) of a function \(w(x,y,t)\) is

for \((i,j,k)\in \mathbb{N}_{*}^{3} \).

Remark 1

We should point out here that the fractional derivative adopted in this work is the Caputo sense, although our work requires only the fractional derivative of the power function which almost all the existing fractional derivative definitions agree with. The fractional derivative of the power function is given by

It is worth mentioning here that different representations of fractional derivatives have recently been proposed based on the exponential law [26] and on the Mittag—Leffler function [27]. Some remarkable works in these trends can be found in [28,29,30].

Remark 2

In case of \({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\), then ternary-FDT (2.3) reduces to the classical three-dimensional differential transform [16].

Definition 2.3

The ternary-fractional differential inverse transform of  is defined as

is defined as

Remark 3

Definition 2.3 evinces that the concept of ternary-FDT is derived from the α̅-FPS.

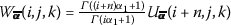

With the aid of equations (2.3) and (2.5), some fundamental properties for ternary-FDT are shown in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.4

Let

, and

, and

be the ternary-FDT of

\(w(x,y,t)\), \(u(x,y,t)\), and

\(v(x,y,t)\)

respectively, and

c

be an arbitrary constant. Then the following properties hold true.

be the ternary-FDT of

\(w(x,y,t)\), \(u(x,y,t)\), and

\(v(x,y,t)\)

respectively, and

c

be an arbitrary constant. Then the following properties hold true.

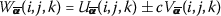

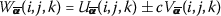

- (i):

-

If \(w(x,y,t)=u(x,y,t)\pm c v(x,y,t)\), then

.

. - (ii):

-

If \(w(x,y,t)=u(x,y,t)\cdot v(x,y,t)\), then

.

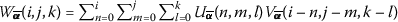

. - (iii):

-

If \(w(x,y,t)= {\frac{\partial ^{n\alpha _{1}} [u(x,y,t) ]}{\partial t^{n\alpha _{1}}}}\), then

.

. - (iv):

-

If \(w(x,y,t)= {\frac{\partial ^{n\alpha _{1}+m\alpha _{2}} [u(x,y,t) ]}{\partial t^{n\alpha _{1}}\partial x^{m\alpha _{2}}}}\), then

.

. - (v):

-

If \(w(x,y,t)= {\frac{\partial ^{n\alpha _{1}+m\alpha _{2}+l\alpha _{3}} [u(x,y,t) ]}{\partial t^{n\alpha _{1}}\partial x^{m\alpha _{2}}\partial y^{l \alpha _{3}}}}\), then

Proof

(i) Follows immediately from Definition 2.2 and the linearity of the fractional derivatives.

(ii)

as desired.

(iii)

(iv) and (v) The proof can be concluded by using the same manner of proof as for (iii). □

Some ternary-FDT for some basic functions around the origin are listed in Table 1.

3 The application side of the suggested method

In this section, we show the worthiness of the suggested technique by solving various well-known partial differential equations that are viewed in the fractal 3D space. The resulting solutions generalized the existing solutions when these equations were projected into the integer 3D space. In all examples, the fractional derivative parameters are assumed to be in \((0,1)\) and \(t, x, y\geq 0\).

Example 1

Consider the following Schrödinger model embedded in the fractal 3D space:

contingent on the initial condition

By implementing the ternary-FDT and harnessing Theorem 2.4, we attain the following transformed recurrence equation of (3.1):

with initial transform coefficients

By recursively solving equation (3.3) with utilizing the initial transform coefficients (3.4), we acquire the following generic transform coefficients:

Therefore, the α̅-memory exact solution of the Schrödinger model (3.1)–(3.2) has the form

We remark here that for \({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\), we attain the closed-form solution \(w(x,y,t)=e^{\mathbf{i}t} (\sin (x)+\sin (y) )\) for the integer copy of the Schrödinger model (3.1)–(3.2).

Example 2

Consider the following wave model embedded in the fractal 3D space:

contingent on the initial conditions

By implementing the ternary-FDT and harnessing Theorem 2.4, we attain the following transformed recurrence equation of (3.7):

with initial transform coefficients

and

By recursively solving equation (3.9) with utilizing the initial transform coefficients (3.10)–(3.11), we acquire the following generic transform coefficients:

Therefore, the α̅-memory exact solution of the wave model (3.7)–(3.8) has the form

We remark here that for \({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\), we attain the closed-form solution \(w(x,y,t)=\cos (2t)\sin (x)\sin (y)\) for the integer copy of the wave model (3.7)–(3.8).

Example 3

Consider the following nonhomogeneous Klein–Gordon model embedded in the fractal 3D space:

contingent on the initial conditions

By implementing the ternary-FDT and harnessing Theorem 2.4, we attain the following transformed recurrence equation of (3.14):

with initial transform coefficients

and

By recursively solving equation (3.16) with utilizing the initial transform coefficients (3.17)–(3.18), we acquire, besides the initial transforms, the following generic transform coefficients:

Therefore, the α̅-memory exact solution of the Klein–Gordon model (3.14)–(3.15) has the form

We remark here that for \({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\), we attain the closed-form solution \(w(x,y,t)=x^{2}+y^{2}+ty^{2}+t^{2}+ \frac{1}{3}t^{3}\) for the integer copy of the Klein–Gordon model (3.14)–(3.15).

Example 4

Consider the following homogeneous linear telegraph model embedded in the fractal 3D space:

contingent on the initial conditions

By implementing the ternary-FDT and harnessing Theorem 2.4, we attain the following transformed recurrence equation of (3.21):

with initial transform coefficients

By recursively solving equation (3.23) with utilizing the initial transform coefficients (3.24), we acquire the following generic transform coefficients:

Therefore, the α̅-memory exact solution of the telegraph model (3.21)–(3.22) has the form

We remark here that for \({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\), we attain the closed-form solution \(w(x,y,t)=e^{x+y-3t}\) for the integer copy of the telegraph model (3.21)–(3.22).

Example 5

Consider the following nonlinear Burgers’ model embedded in the fractal 3D space:

contingent on the initial condition

By implementing the ternary-FDT and harnessing Theorem 2.4, we attain the following transformed recurrence equation of (3.27):

with initial transform coefficients

By recursively solving equation (3.29) with utilizing the initial transform coefficients (3.30), we acquire the following relation among the transform coefficients:

where  is given recursively by

is given recursively by

and for \(i\geq 2\)

Therefore, the α̅-memory solution of Burgers’ model (3.27)–(3.28) is

We should point out here that  as \({\overline{ \pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\). Thus, the closed-form solution for the integer copy of (3.27)–(3.28) is

as \({\overline{ \pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\). Thus, the closed-form solution for the integer copy of (3.27)–(3.28) is

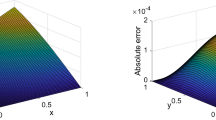

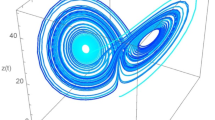

4 Graphical analysis and discussions

In the present part, we choose Burgers’ model (3.27)–(3.28) to illustrate and comprehend the impact of the Caputo fractional derivative. Figure 1 shows a sample of the cross-sections attitude for the 8th series solution of (3.34) for diverse values of the fractional parameters in particular domains. In all situations, we have continuous successive behavior as long as the fractional parameters get closer to the integer derivative order. Therefore, the role of order-variation of the fractional derivative is to preserve a homotopy mapping from the present value of the solution “\({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (0,0,0)\)” to its instantaneous rate of change “\({\overline{\pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\)”. This interpretation is made by the phenomena of a sequential-asymptotic propagation of the solution as the fractional parameters vary from 0 to 1 as depicted in Fig. 1. Further, the cross-sections of the integer derivative order reconcile with their associates when \({\overline{ \pmb{\alpha }}}\rightarrow (1,1,1)\). This shows the generality of α̅-Burgers’ model.

5 Conclusions

In this work, we have viewed several well-known partial differential equations in the fractal 3D space and provided their solutions analytically in terms of an α̅-FPS. An adaptation of the fractional differential transform method by means of a new α̅-FPS representation is developed and used to obtain a complete fractional solution form of these new models. The projections of these solutions into the integer 3D space reconcile with the solutions of the classical copies of these models. Moreover, the proposed method has been autonomously constructed without the need to convert the equation into solvable and perturbation or linearization terms. In summary, we have successfully provided a comprehensive analytic study of partial differential equations that are fully embedded in the fractal 3D space.

References

West, B., Bologna, M., Grigolini, P.: Physics of Fractal Operators. Springer, Berlin (2012)

Gomez-Aguilar, J.F., Miranda-Hernandez, M., Lopez-Lopez, M.G., Alvarado-Martínez, V.M., Baleanu, D.: Modeling and simulation of the fractional space–time diffusion equation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 30(1–3), 115–127 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2015.06.014

Zhang, W., Simizu, N.: Damping properties of the viscoelastic material described by fractional Kelvin–Voigt model. JSME Int. J. Ser. C 42(1), 1–9 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1299/jsmec.42.1

Zabusky, N.J., Kruskal, M.D., Baleanu, D.: Interaction of “solitons” in a collisionless plasma and the recurrence of initial states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15(6), 240–243 (1965). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.15.240

Heymans, N., Podlubny, I.: Physical interpretation of initial conditions for fractional differential equations with Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives. Rheol. Acta 45(5), 765–771 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00397-005-0043-5

Tavassoli, M.H., Tavassoli, A., Ostad Rahimi, M.R.: The geometric and physical interpretation of fractional order derivatives of polynomial functions. Differ. Geom. Dyn. Syst. 15, 93–104 (2013)

Du, M., Wang, Z., Hu, H.: Measuring memory with the order of fractional derivative. Sci. Rep. 3, 3431 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03431

Jaradat, I., Al-Dolat, M., Al-Zoubi, K., Alquran, M.: Theory and applications of a more general form for fractional power series expansion. Chaos Solitons Fractals 108, 107–110 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2018.01.039

Alquran, M., Jaradat, I.: A novel scheme for solving Caputo time-fractional nonlinear equations: theory and application. Nonlinear Dyn. 91, 2389–2395 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-4019-7

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Al-Khaled, K.: An analytical study of physical models with inherited temporal and spatial memory. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, 162 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-12007-1

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Abdel-Muhsen, R.: An analytical framework of 2D diffusion, wave-like, telegraph, and Burgers’ models with twofold Caputo derivatives ordering. Nonlinear Dyn. 93, 1911–1922 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4297-8

Alquran, M., Jaradat, I., Abdel-Muhsen, R.: Embedding \((3 + 1)\)-dimensional diffusion, telegraph, and Burgers’ equations into fractal 2D and 3D spaces: an analytical study. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. (2018, in press)

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Al-Dolat, M.: Analytic solution of homogeneous time-invariant fractional IVP. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1601-3

Zhou, J.K.: Differential Transformation and Its Applications for Electrical Circuits, pp. 1279–1289. Huazhong University Press, Wuhan (1986) (in Chinese)

Chen, C.K., Ho, S.H.: Solving partial differential equations by two dimensional differential transform. Appl. Math. Comput. 106(2–3), 171–179 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0096-3003(98)10115-73

Ayaz, F.: Solutions of the system of differential equations by differential transform method. Appl. Math. Comput. 147(2), 547–567 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0096-3003(02)00794-4

Arikoglu, A., Ozkol, I.: Solution of fractional differential equations by using differential transform method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 34(5), 1473–1481 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.09.004

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Yousef, F., Momani, S., Baleanu, D.: An avant-garde handling of temporal-spatial fractional physical models. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. (2019, accepted)

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Yousef, F., Momani, S., Baleanu, D.: On \((2 + 1)\)-physical models endowed with decoupled spatial and temporal memory indices. Eur. Phys. J. Plus (2019, accepted)

Singh, J., Kumar, D., Baleanu, D., Sushila, R.: On the local fractional wave equation in fractal strings. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 42(5), 1588–1595 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.5458

Singh, J., Secer, A., Swroop, R., Kumar, D.: A reliable analytical approach for a fractional model of advection-dispersion equation. Nonlinear Eng. 8(1), 107–116 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1515/nleng-2018-0027

Singh, J., Kumar, D., Baleanu, D., Sushila, R.: An efficient numerical algorithm for the fractional Drinfeld–Sokolov–Wilson equation. Nonlinear Eng. 335, 12–24 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2018.04.025

Alquran, M., Jaradat, I., Sivasundaram, S.: Elegant scheme for solving Caputo-time-fractional integro-differential equations. Nonlinear Stud. 25(2), 385–393 (2018)

Ali, M., Alquran, M., Jaradat, I.: Asymptotic-sequentially solution style for the generalized Caputo time-fractional Newell–Whitehead–Segel system. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019, 70 (2019)

Alquran, M., Jaradat, I., Baleanu, D., Abdel-Muhsen, R.: An analytical study of \((2 + 1)\)-dimensional physical models embedded entirely in fractal space. Rom. J. Phys. 64, 103 (2019)

Caputo, M., Fabrizio, M.: A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 73–85 (2015)

Atangana, A., Baleanu, D.: New fractional derivatives with non-local and nonsingular kernel: theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 20(2), 763–769 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI160111018A

Kumar, D., Singh, J., Baleanu, D., Sushila, R.: Analysis of regularized long-wave equation associated with a new fractional operator with Mittag-Leffler type kernel. Physica A 492, 155–167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2017.10.002

Kumar, D., Singh, J., Baleanu, D.: A new analysis of Fornberg–Whitham equation pertaining to a fractional derivative with Mittag-Leffler type kernel. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133(2), 70 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-11934-y

Singh, J., Kumar, D., Baleanu, D.: On the analysis of fractional diabetes model with exponential law. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 231 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1680-1

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions, which substantially improved the quality of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The work of the first, third, and fourth authors was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that this study was accomplished in collaboration with the same responsibility. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousef, F., Alquran, M., Jaradat, I. et al. Ternary-fractional differential transform schema: theory and application. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 197 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2137-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2137-x

.

. .

. .

. .

.