Abstract

We analyze the positive solutions to

where \(\Omega_{0}=(0,1)\) or is a bounded domain in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\), \(n =2,3\), with smooth boundary and \(|\Omega_{0}|=1\), and λ, γ are positive parameters. Such steady state equations arise in population dynamics encapsulating assumptions regarding the patch/matrix interfaces such as patch preference and movement behavior. In this paper, we will discuss the exact bifurcation diagram and stability properties for such a steady state model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Habitat fragmentation creates landscape-level spatial heterogeneity which influences the population dynamics of the resident species. Of particular interest, fragmentation often leads to declines in abundance of the species as the fragmented landscape becomes more susceptible to edge effects between the remnant habitat patches and the lower quality human-modified “matrix” surrounding these focal patches [1,2,3]. Studies of movement behavior in response to different habitat edge conditions clearly demonstrate that the composition of the matrix can influence emigration rates, patterns of movement, and within-patch distributions of a species (e.g., [4,5,6]). Movement behavior has been shown to be very species-specific [7], even in the same fragmented habitat.

Even though the task of connecting the wealth of empirical information available about individual movement and mortality in response to matrix composition to predictions about patch-level persistence is indeed formidable, the reaction–diffusion framework and its underlying random walk models have seen some success in addressing this connection [8]. The reaction–diffusion framework’s major strength is that the model’s dynamics can be analyzed mathematically, providing important patch-level predictions of population persistence, leading to its wide adoption by ecologists ([9, 10], and [11]). This framework is also ideally suited to handle fragmentation and edge-mediated effects as the partial differential equation(s) involved require explicit definition of edge behavior via boundary conditions ([10] and [2]).

In [12], the authors formalize a framework to facilitate the connection between small-scale movement and patch-level predictions of persistence through a mechanistic model based on reaction–diffusion equations. The model is capable of incorporating essential information about edge-mediated effects such as patch preference, movement behavior (e.g., emigration rates, patterns of movement, and within-patch distributions), and matrix-induced mortality at the patch/matrix interface. The authors then mathematically analyze the model’s predictions of persistence with a general logistic-type growth term. In particular, the focus of [12] is to provide bounds on demographic attributes and patch size in order for the model to predict persistence of a species in a given patch based on assumptions on the patch/matrix interface and to explore their sensitivity to demographic attributes both in the patch and the matrix, as well as patch size and geometry. The purpose of this present work is to provide an exact description of the bifurcation curve of positive steady states to their model when the growth term is logistic. In the following subsections, we will briefly summarize the modeling framework and boundary condition derivation given in [12] and present our main results. We provide the proof of these results in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, for the case \(n=1\), we provide an alternative proof of our results in the case \(\Omega=(0,1)\) via a quadrature method and discuss the evolution of the bifurcation curves as a model parameter varies. We discuss biological implications of our results in Sect. 4. Finally, in Appendix 1, we provide the derivation of the boundary condition focused on in this paper, and in Appendix 2, we provide results on certain eigenvalue problems that we employ in the proof of our main result.

1.1 Modeling framework

We consider a patch \(\Omega_{0}\) in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) when \(n = 1, 2\), or 3 with \(\vert \Omega_{0} \vert = 1\), where

We assume here that the boundary of \(\Omega_{0}\) (denoted by \(\partial \Omega_{0}\)) is smooth. Now, we define the focal patch as \(\Omega= \{ \ell x | x \in\Omega_{0} \}\) yielding

where ℓ is a positive parameter representing the patch size (see [10]). In this way, we are able to separate the combined effects of patch size (ℓ) and patch geometry (geometry of \(\Omega_{0}\)) on population persistence. In the model, \(u(t, x)\) represents the density of a theoretical population inhabiting Ω. Here, the variable t represents time and x represents spatial location within Ω. The model is then as follows:

where the parameter D is the diffusion rate inside the patch, \(D_{0}\) is the diffusion rate in the matrix surrounding Ω, r is the patch intrinsic growth rate, \(S_{0}\) is the death rate in the matrix, and κ is a parameter encapsulating assumptions regarding the patch/matrix interface such as patch preference and movement behavior. Also, \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial\eta}\) represents the outward normal derivative of u, r is the intrinsic growth rate of the population inside Ω, K is the carrying capacity, and \(u_{0}\) is the initial distribution of population density in the patch. The parameters D, \(D_{0}\), \(S_{0}\), r, K, and κ are always positive. Note that the boundary condition in (1) is derived in Appendix 1.

The interface scenarios listed in [12] correspond to certain values of the parameter κ as originally derived in [13]. Recall that in the random walk model, organisms are assumed to move the step size Δx with probability p every Δt units of time. The diffusion rate is then obtained by taking parabolic limits in such a way that

is constant (see, for example, [9, 14], and [10]). Table 1 taken directly from [12] lists each scenario along with their κ-value, name, biological interpretation, and selected references for each scenario. Note that α will denote the probability that an organism remains in the patch upon reaching the patch/matrix interface.

Now, applying the change of variables \(\tilde{t} = rt\), \(\tilde{x} = \frac{x}{\ell}\), \(v=\frac{u}{K}\), and \(\lambda= \frac{r \ell ^{2}}{D}\), (1) reduces to (after dropping the tilde):

with steady state equation

where λ is unitless and \(\vert \Omega_{0} \vert = 1\). The value of the unitless parameter γ is given in Table 2 listed by interface scenario.

1.2 Statement of the main result

In this paper, we study existence, nonexistence, uniqueness results, and stability properties for (4). The following definitions of stability and instability presented here come from Lyapunov stability, which is defined with respect to initial perturbations (see, for example, [19]). A solution \(v_{s}(x)\) of (4) is said to be stable if for every \(\epsilon> 0\) there exists \(\delta> 0\) such that \(\|v(t, \cdot ) - v_{s}\|_{\infty}< \epsilon\) for \(t > 0\) whenever \(\|v_{0} - v_{s}\|_{\infty}< \delta\), where \(v(t, x)\) is the solution of (3). If, in addition, \(\|v(t, \cdot) - v_{s}\|_{\infty}\rightarrow 0\) as \(t \rightarrow\infty\), then \(v_{s}\) is said to be asymptotically stable. In the case that this holds for all initial functions \(v(0, x)\), then \(v_{s}\) is said to be globally asymptotically stable. The steady state \(v_{s}\) is said to be unstable if it is not stable. Finally, \(v_{s}(x)\) is said to be an isolated steady state if there exists a neighborhood \(N_{v_{s}}\) of \(v_{s}\) in \(C(\overline{\Omega})\) such that \(v_{s}\) is the only steady state solution in \(N_{v_{s}}\). To precisely state our results, we first consider the eigenvalue problem

It follows that (5) has a principal eigenvalue \(\lambda _{1}(\gamma) >0\) (see Appendix 2). Taking w as an eigenfunction such that \(\|w\|_{\infty}= 1\) and w is nonnegative, we first note that by the maximum principle \(w > 0\); \(\Omega_{0}\). Now, if \(w(x_{0}) = 0\) on \(\partial\Omega_{0}\), then by Hopf’s lemma we must have \(\frac {\partial w}{\partial\eta} |_{x_{0}} < 0\) and thus \((\frac {\partial w}{\partial\eta} + \gamma\sqrt{\lambda}w ) |_{x_{0}} \neq0\). Hence, \(w>0\) in \(\overline{\Omega}_{0}\). Now, we establish the following.

Theorem 1

Given any \(\gamma> 0\):

-

(a)

If \(\lambda> \lambda_{1} (\gamma)\), then the trivial solution of (4) is unstable and there exists a unique positive solution \(v_{\lambda}\) to (4) which is globally asymptotically stable. Furthermore, \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to0^{+}\) as \(\lambda\to\lambda_{1} (\gamma)^{+}\) and \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to1\) as \(\lambda\to\infty\);

-

(b)

If \(0 < \lambda\leq\lambda_{1} (\gamma)\), then the trivial solution of (4) is globally asymptotically stable and there is no positive solution to (4).

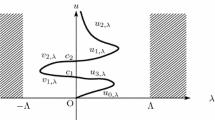

Note that \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \rightarrow0\) as \(\gamma\rightarrow 0^{+}\). Theorem 1 is illustrated in Fig. 1. We prove our results via the method of sub-super solutions and the principle of linearized stability.

2 Proof of Theorem 1

In this section, we provide a proof of our main results given in Theorem 1.

Proof

Let λ and γ be fixed, and let \(\sigma_{1}\) be the principal eigenvalue and \(\phi>0\) in \(\overline{\Omega}_{0}\) be the corresponding eigenfunction such that \(\|\phi\|_{\infty}=1\) to the eigenvalue problem:

Note that (6) is a linearization of (4) about the trivial solution. We also recall below the principle of linearized stability (see Lemma 1) given in [20, Theorem 1.1] (but also see [10, pp. 147–148] for example). Let \(\delta_{1}\) be the principal eigenvalue of

with corresponding normalized eigenfunction \(\phi(x) > 0\); \(\Omega_{0}\). See Appendix 2 for justification of the existence of the principal eigenvalues of (6) and (7).

Lemma 1

Let \(\delta_{1}\) be the principal eigenvalue of (7). Then the following hold:

-

(a)

If \(\delta_{1} \geq0\), then the trivial solution of (4) is stable.

-

(b)

If \(\delta_{1} < 0\), then the trivial solution of (4) is unstable.

Note that by Lemma 5 in Appendix 2, we have that \(\operatorname{sign}(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)) = \operatorname{sign}(\sigma_{1}(\lambda , \gamma))\). Thus, it suffices to only consider the sign of \(\sigma _{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\).

To prove (a), let \(\lambda> \lambda_{1} (\gamma)\). (By Lemma 4 in Appendix 2, we have that \(\sigma _{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\) and hence the zero solution is unstable.) Next we will show the existence of a positive solution \(v_{\lambda}\) with the property that \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to0^{+}\) as \(\lambda\to \lambda_{1} (\gamma)^{+}\). Let \(\psi:=m \phi\) for \(m >0\) to be chosen later with ϕ the principal eigenfunction of (6) corresponding to \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\). Then we have

and

Hence \(\psi= m_{1} \phi\) with any \(m_{1} \in (0, - \frac{\sigma _{1}}{\lambda} )\) is a strict subsolution of (4) (since \(\| \phi\|_{\infty}=1\)), and \(\psi=m_{2} \phi\) with

is a supersolution of (4). Clearly \(m_{2} > m_{1}\), and hence by the method of sub-super solutions (see [21]), (4) has a positive solution \(v_{\lambda}\) such that \(m_{1} \phi< v_{\lambda}\leq m_{2} \phi\) for \(\lambda> \lambda_{1} (\gamma)\). Note here that when \(\lambda\to\lambda_{1} (\gamma)^{+}\), \([-\sigma_{1}] \to 0^{+}\) while \(\min_{\overline{\Omega}_{0}} \phi\not\to0\) since it approaches the eigenfunction corresponding to the principal eigenvalue \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) of (5), which we discussed earlier. Thus, \(m_{1} \to0^{+}\) and \(m_{2} \to0^{+}\), and, in particular, \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to0^{+}\) as \(\lambda\to\lambda_{1}(\gamma)^{+}\).

Next, we show that this positive solution is, in fact, unique. To see this, we assume that (4) has two positive solutions \(v_{1}\) and \(v_{2}\). Without loss of generality, we can assume that \(v_{2}\) is the maximal positive solution (since \(w=1\) is a global supersolution, this maximal positive solution must exist when a positive solution exists), and hence \(v_{2} \ge v_{1}\) in \(\overline{\Omega}_{0}\). Supposing \(v_{1}\) and \(v_{2}\) are distinct, by integration by parts (Green’s second identity), we obtain

while

This is a contradiction, and hence \(v_{1} \equiv v_{2}\) and (4) has a unique positive solution \(v_{\lambda}\) for \(\lambda> \lambda_{1} (\gamma)\).

Also, to prove the property \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to1\) as \(\lambda \to\infty\), we note that the Dirichlet boundary value problem

has a unique positive solution \(\overline{\psi}_{\lambda}\) for \(\lambda> \lambda_{1}^{D}\) with \(\|\overline{\psi}_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}<1\) and \(\|\overline{\psi}_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to1^{-}\) as \(\lambda\to \infty\), where \(\lambda_{1}^{D}>0\) is the principal eigenvalue of

See Fig. 2 for an illustration of the structure of positive solutions of (8).

Since \(\frac{\partial\overline{\psi}}{\partial\eta} < 0\) in \(\Omega_{0}\), clearly \(\overline{\psi}_{\lambda}\) is a subsolution to (4) for \(\lambda\gg1\), and since \(w=1\) is a supersolution to (4) for \(\lambda> 0\), we must have \(v_{\lambda}\in [ \overline{\psi}_{\lambda}, 1 ]\) and hence \(\|v_{\lambda}\|_{\infty}\to1^{-}\) as \(\lambda\to\infty\).

Now, to show the stability properties of \(v_{\lambda}\), recall that we have \(\psi= m_{1} \phi\) is a strict subsolution for all \(m_{1} \in (0, -\frac{\sigma_{1}}{\lambda} )\) and \(Z \equiv M\) is a strict supersolution for all \(M > 1\). This implies that \(\phi< v_{\lambda}< Z\) and ϕ can be made arbitrarily small and Z can be made arbitrarily large. This fact combined with a result such as Theorem 6.7 of Chap. 5 in [19] immediately shows that \(v_{\lambda}\) is globally asymptotically stable, proving (a).

To prove (b), we first show the nonexistence of a positive solution of (4) when \(\lambda\leq\lambda_{1} (\gamma)\) (which by Lemma 4 in Appendix 2 implies \(\sigma_{1} \geq0\)). Assume to the contrary that v is a positive solution of (4), then by Green’s second identity, we obtain

while

Hence, we have a contradiction and therefore (4) has no positive solution when \(\lambda\leq\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\). Finally, since \(\lambda\leq\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) implies \(\sigma _{1}(\lambda, \gamma) \geq0\), the trivial solution of (4) is stable. But since there is no positive solution of (4) for \(\lambda\leq\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), the trivial solution must be globally asymptotically stable. Hence, Theorem 1 is proven. □

3 One-dimensional problem

In the case \(\Omega_{0}=(0,1)\), equation (4) reduces to the two-point boundary value problem

From Theorem 1, (10) has a unique positive solution when \(\lambda>\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) and no positive solution when \(\lambda<\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), where \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) is the principal eigenvalue of

A straightforward calculation will show that \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma )=4 (\frac{\pi}{2} - \tan^{-1} (\frac{1}{\gamma} ) )^{2}\). Note that as \(\gamma\to0^{+}\), \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \to 0\) and as \(\gamma\to\infty\), \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \to\pi^{2}=\lambda_{1}^{D}\).

We now use the quadrature method introduced by Laetsch in [22] and further extended in [23,24,25,26], and [27]. Suppose that u is a positive solution with \(u(\frac {1}{2})=\rho\) (say) and \(u(0)=q\) (say). Note that since (10) is autonomous, the solution must be symmetric about \(t=\frac {1}{2}\) and take the form shown in Fig. 3.

Multiplying the differential equation in (10) by \(u'\) and integrating yields

where \(F(z)=\int_{0}^{z} s(1-s) \,dt\). Further integration yields

and hence, setting \(t \to\frac{1}{2}\), we obtain

Now the boundary conditions require that ρ and q satisfy

Note that given \(\rho\in(0,1)\), there exists unique \(q=q(\rho)\in (0,\rho)\) satisfying (12), and we can show that

is well-defined and continuous on \((0,1)\).

Further, given \(\rho\in(0,1)\), for λ satisfying

(10) has a positive solution of the form given in Fig. 3 defined by

Hence (13) describes the bifurcation diagram for positive solutions of (10). Using Mathematica computation, we provide below this bifurcation diagram for several values of γ. In particular, we illustrate the evolution of the bifurcation diagram as \(\gamma\to0^{+}\) and \(\gamma\to\infty\) in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Note that when \(\gamma\to0^{+}\), we approach the Neumann boundary condition case, and when \(\gamma\to\infty\), we approach the Dirichlet boundary condition case.

Bifurcation curves for (10) as \(\gamma\to\infty\). The curves correspond (from left to right) to \(\gamma=1\), \(\gamma =10\), and \(\gamma=100\). Note that as \(\gamma\to\infty\), the bifurcation curves approach \(\pi ^{2}\), which is the first eigenvalue of the Dirichlet problem

Bifurcation curves for (10) as \(\gamma\to0^{+}\). The curves correspond (from left to right) to \(\gamma=0.1\), \(\gamma =0.5\), and \(\gamma=1\). Note that as \(\gamma\to0^{+}\), the bifurcation curves approach 0, which is the first eigenvalue of the Neumann problem

4 Biological implications of our results

These model results give important predictions on population persistence at the patch level based solely on demographic parameters, e.g., patch diffusion rate and intrinsic growth rate, as well as matrix diffusion rate and death rate. We note that our analysis covers all four of the interface scenarios listed in Table 1. Although the exact definition of γ depends upon the interface scenario given (see Table 2), the qualitative behavior of the persistence of the organism is the same as γ varies. Notice that the principal eigenvalue \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) of (6) plays a crucial role in determining the dynamics of the model. In fact, it represents the fastest possible growth rate for the linear growth model corresponding to (3) (see [3] or [10]).

As indicated in Theorem 1 (and the proof therein), when \(\lambda\leq\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) we have that \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) \geq0\), and the only nonnegative steady state of (3) is the trivial one, \(u \equiv0\). In this case, the model predicts extinction for any nonnegative initial population density profile. In fact, loses due to mortality in the matrix outpace the reproductive rate in the patch. Thus, the theoretical organism cannot colonize the patch, and any remnant population in the patch will become extinct. However, when \(\lambda> \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), we have that \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\) and (3) admits a unique steady state that is positive in Ω̅ such that all positive initial population density profiles will propagate to this steady state over time. In this case, the global nature of the stability of the positive steady state gives a fairly strong notion of persistence of the species. The patch is large enough in this case to shield a sufficient proportion of the population from mortality induced by the hostile matrix. This prediction leads to a formula for minimum patch size of the population given as \(\ell^{*}(\gamma) = \sqrt{\frac {D}{r} \lambda_{1}(\gamma)}\). Note that this formula can be numerically estimated and depends upon parameters in the patch (diffusion rate and intrinsic growth rate), parameters in the matrix via γ (diffusion rate and death rate), and the geometry of the patch \(\Omega_{0}\).

This notion of a minimum patch size agrees with the well-known notion of a minimum core area (in the case of \(n = 2\)) requirement. Note that \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) can be viewed as a quantification of the loss of the population due to interactions with the hostile matrix where γ encapsulates parameters regarding the hostile matrix. Also, it is easy to see that \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \to\lambda_{1}^{D}\) as \(\gamma\to\infty\), and this reveals an important model prediction of the existence of a maximum possible effect of population loss due to the hostile matrix. Patches with a lethal matrix can still guarantee a prediction of persistence as long as the patch size is larger than \(\sqrt{\frac{D}{r} \lambda_{1}^{D}}\), where the maximum effect of the lethal matrix on the population is quantified in \(\lambda_{1}^{D}\). This minimum patch size approaches infinity if either (1) the patch diffusion rate is arbitrarily large, since a large diffusion rate ensures that a very high proportion of the population will encounter loss at the patch/matrix interface, or (2) the intrinsic growth rate is arbitrarily small, which for a fixed patch diffusion rate will imply that the population is not able to recover the loss associated with interaction with hostile matrix.

References

Ries, L., Fletcher, R.J. Jr., Battin, J., Sisk, T.D.: Ecological responses to habitat edges: mechanisms, models, and variability explained. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35(1), 491–522 (2004)

Fagan, W.F., Cantrell, R.S., Cosner, C.: How habitat edges change species interactions. Am. Nat. 153(2), 165–182 (1999)

Cantrell, R.S., Cosner, C., Fagan, W.F.: Competitive reversals inside ecological reserves: the role of external habitat degradation. J. Math. Biol. 37(6), 491–533 (1998)

Tscharntke, T., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Kruess, A., Thies, C.: Contribution of small habitat fragments to conservation of insect communities of grassland–cropland landscapes. Ecol. Appl. 12(2), 354–363 (2002)

Schooley, R.L., Wiens, J.A.: Movements of cactus bugs: patch transfers, matrix resistance, and edge permeability. Landsc. Ecol. 19(7), 801–810 (2004)

Haynes, K.J., Cronin, J.T.: Interpatch movement and edge effects: the role of behavioral responses to the landscape matrix. Oikos 113(1), 43–54 (2006)

Reeve, J.D., Cronin, J.T.: Edge behaviour in a minute parasitic wasp. J. Anim. Ecol. 79(2), 483–490 (2010)

Maciel, G.A., Lutscher, F.: How individual movement response to habitat edges affects population persistence and spatial spread. Am. Nat. 182(1), 42–52 (2013)

Turchin, P.: Quantitative Analysis of Movement: Measuring and Modeling Population Redistribution in Animals and Plants. Sinauer, Sunderland (1998)

Cantrell, R.S., Cosner, C.: Spatial Ecology Via Reaction–Diffusion Equations. Mathematical and Computational Biology, p. 411. Wiley, Chichester (2003)

Holmes, E.E., Lewis, M.A., Banks, R.R.V.: Partial differential equations in ecology: spatial interactions and population dynamics. Ecology 75(1), 17–29 (1994)

Cronin, J.T., Goddard, J. II, Shivaji, R.: Effects of patch matrix and individual movement response on population persistence at the patch-level. Preprint (2017)

Maciel, G., Lutscher, F.: How individual movement response to habitat edges affects population persistence and spatial spread. Am. Nat. 182(1), 42–52 (2013)

Okubo, A.: Diffusion and Ecological Problems: Mathematical Models. Biomathematics, vol. 10. Springer, Berlin (1980)

Ludwig, D., Aronson, D.G., Weinberger, H.F.: Spatial patterning of the spruce budworm. J. Math. Biol. 8, 217–258 (1979)

Ovaskainen, O., Cornell, S.J.: Biased movement at a boundary and conditional occupancy times for diffusion processes. J. Appl. Probab. 40(3), 557–580 (2003)

Cantrell, R.S., Cosner, C.: Diffusion models for population dynamics incorporating individual behavior at boundaries: applications to refuge design. Theor. Popul. Biol. 55(2), 189–207 (1999)

Cantrell, R.S., Cosner, C.: Density dependent behavior at habitat boundaries and the Allee effect. Bull. Math. Biol. 69, 2339–2360 (2007)

Pao, C.V.: Nonlinear Parabolic and Elliptic Equations, p. 777. Plenum, New York (1992)

Goddard, J. II, Shivaji, R.: Stability analysis for positive solutions for classes of semilinear elliptic boundary-value problems with nonlinear boundary conditions. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. A 147, 1019–1040 (2017)

Inkmann, F.: Existence and multiplicity theorems for semilinear elliptic equations with nonlinear boundary conditions. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 31(2), 213–221 (1982)

Laetsch, T.: The number of solutions of a nonlinear two point boundary value problem. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 20, 1–13 (1970/71)

Anuradha, V., Maya, C., Shivaji, R.: Positive solutions for a class of nonlinear boundary value problems with Neumann–Robin boundary conditions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 236(1), 94–124 (1999)

Goddard, J. II, Lee, E.K., Shivaji, R.: Population models with nonlinear boundary conditions. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. Conf. 19, 135–149 (2010)

Goddard, J. II, Morris, Q., Son, B., Shivaji, R.: Bifurcation curves for singular and nonsingular problems with nonlinear boundary conditions. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2018, 26 (2018)

Goddard, J. II, Price, J., Shivaji, R.: Analysis of steady states for classes of reaction–diffusion equations with U-shaped density dependent dispersal on the boundary (2017, in press)

Miciano, A.R., Shivaji, R.: Multiple positive solutions for a class of semipositone Neumann two point boundary value problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 178(1), 102–115 (1993)

Rivas, M.A., Robinson, S.: Eigencurves for linear elliptic equations. European Journal ESAIM (to appear)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions greatly improved this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation via grant DMS-1516560 for the first author and grant DMS-1516519 for the last author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Derivation of the boundary condition in (1)

Here, we summarize the derivation of the boundary condition in (1) from [12]. Their approach combines the ideas from [8] and [3] under the patch/matrix interface conditions given in these respective papers. The boundary condition in (1), namely

allows modeling of the effects of movement behavior changes in response to the patch/matrix interface and hostility of the matrix surrounding the patch. To see this, [12] combines the approach of modeling the effects of a hostile matrix in [15] with the interface conditions given in [8]. Following the derivation in [15], let us consider a one-dimensional patch \(\Omega= (0, \ell)\) (\(\ell> 0\) denotes the patch size) surrounded by an infinite “sea” of hostile territory. The population density w is subject to the following growth law exterior to Ω:

where \(D_{0}\) is a positive parameter representing the diffusion rate and \(S_{0}\) is a positive parameter representing the death rate of the organism in the matrix. Continuity of flux is a natural condition that will imply all organisms leaving the patch will enter the matrix and organisms leaving the matrix will enter the patch (see [8]). Thus, no organisms are introduced or lost at the interface. However, a discontinuity is introduced in the density at the patch/matrix interface to account for changes in movement behavior. Now, let D be the diffusion rate inside Ω and follow the random walk derivation given in [8] to yield the interface conditions:

where κ is a positive, unitless parameter, η is the outward normal direction for the patch, and \(\eta_{0}\) is the inward normal direction for the matrix. The only steady state solution to (15) which is nonnegative and bounded for \(x < 0\) is of the form \(w(x) = C_{1} e^{\sqrt{\frac{S_{0}}{D_{0}}} x}\); \(x \leq0\), where \(C_{1} \geq0\) is a constant (see [15]). Hence, applying the interface conditions (16) and (17) to this solution yields

A similar argument for \(x = \ell\) also yields

or equivalently,

For domains in higher dimensions with arbitrary boundary shapes, easily extending such a derivation is not possible. In this paper, we make the assumption that (2) is a reasonable approximation of the boundary behavior of an organism, where the parameter \(S_{0}\) can be interpreted as a death rate in the matrix, \(D_{0}\) as the diffusion rate in the matrix, and κ as a measure of the discontinuous “jump” in density at the patch/matrix interface.

Appendix 2: Results for eigenvalue problems (5), (6), and (7)

First we consider the eigenvalue problem

for given \(\mu\in\mathbb{R}\). We recall the following result from [28].

Lemma 2

For each \(\mu\in\mathbb{R}\), (21) has a principal eigenvalue \(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu)\), and the eigencurve \(\bar{\lambda }_{1}(\mu) \subset\mathbb{R}^{2}\) is Lipschitz continuous, strictly decreasing, and concave. Furthermore, \(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(0) = 0\) and the eigenfunction associated with any point on \(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu )\) is strictly positive in \(\Omega_{0}\).

We now state and prove a result regarding the limiting value of \(\bar {\lambda}_{1}(\mu)\) as \(\mu\rightarrow-\infty\). Figure 6 illustrates Lemma 3.

Lemma 3

\(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu) \rightarrow\lambda_{1}^{D}\) as \(\mu\rightarrow -\infty\), where \(\lambda_{1}^{D}\) is the principal eigenvalue of (9).

Proof

We note that, for any \(\mu\in\mathbb{R}\), we may characterize \(\bar {\lambda}_{1}(\mu)\) by

Let \(\lambda_{1}^{D}\) be the principal eigenvalue of (9) with corresponding normalized eigenfunction \(\phi_{1}^{D}\) chosen such that \(\int_{\Omega_{0}} \phi_{1}^{D}=1\). Testing (22) with \(u=1\) and \(u=\phi_{1}^{D}\) shows that

and

respectively. Taking a sequence \(\mu_{n} \to- \infty\) such that the corresponding eigenfunctions \(u_{n}\), without loss of generality, satisfy \(\int _{\Omega_{0}} u_{n}^{2} \,dx =1\), we observe that

Since \(\mu_{n}<0\), we have \(0=\bar{\lambda}_{1}(0)<\bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu _{n}) < \lambda_{1}^{D}\). By Lemma 2, \(\lim_{\mu\to- \infty } \bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu)=\bar{\lambda}_{1}(-\infty)\le\lambda_{1}^{D}\) for some \(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(-\infty) \in\mathbb{R}\). Without loss of generality, we may assume \(-\mu_{n} \int_{\partial\Omega_{0}} u_{n}^{2} \,ds \to\alpha\ge0\), and thus \(\int_{\partial\Omega_{0}} u_{n}^{2} \to0\).

Since \(\{u_{n}\}\) is bounded in \(H^{1}(\Omega_{0})\), we may select a subsequence so that \(u_{n} \rightharpoonup u\) in \(H^{1}(\Omega_{0})\), \(u_{n} \to u\) in \(L^{2}(\Omega_{0})\) and in \(L^{2}(\partial\Omega_{0})\). It follows that \(\int_{\Omega_{0}} u^{2} \,dx =1\) and \(\int_{\partial\Omega_{0}} u^{2} \,ds =0\), and hence \(u \in H^{1}_{0}(\Omega_{0})\).

By the weak lower semicontinuity of \(\int_{\Omega_{0}} |\nabla u|^{2} \,dx\), we get that

But by Poincare’s inequality, we have \(\lambda_{1}^{D} \le\int_{\Omega _{0}} |\nabla u|^{2} \,dx\), and hence we must have \(\alpha=0\) and \(\bar {\lambda}_{1}(-\infty) = \lambda_{1}^{D}\). Furthermore, \(\int_{\Omega_{0}} |\nabla u|^{2} \,dx = \lambda_{1}^{D}\), and thus, without loss of generality, \(u=\phi_{1}^{D}\). Moreover, \(\lim_{n \to\infty} \int_{\Omega_{0}} |\nabla u_{n}|^{2} \,dx = \int_{\Omega_{0}} |\nabla u|^{2} \,dx\), and hence \(u_{n} \to u=\phi_{1}^{D}\) in \(H^{1}(\Omega)\). □

Next, we consider the eigenvalue problem (5), namely

for given \(\gamma> 0\). It is easy to see that the principal eigenvalue \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) of (23) is nothing but the y-coordinate of the intersection of the curves \(\bar{\lambda}_{1}(\mu )\) and \(\frac{\mu^{2}}{\gamma^{2}}\) (see Fig. 7). It is also straightforward to show that \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) is an increasing function of γ, \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \rightarrow\lambda_{1}^{D}\) as \(\gamma\rightarrow\infty\), and \(\lambda_{1}(\gamma) \rightarrow 0\) as \(\gamma\rightarrow0\) (see Fig. 8). Next, we consider the eigenvalue problem (6), namely, for given \(\lambda> 0\) and \(\gamma> 0\),

Once again, it is easy to see that the principal eigenvalue \(\sigma _{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) of (24) exists and must satisfy

(see Fig. 9). Furthermore, the following result holds.

Lemma 4

If \(\lambda< \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), then \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > 0\), and if \(\lambda= \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), then \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) = 0\). Also, if \(\lambda> \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), then \(\sigma _{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\).

Proof

Note that if \(\lambda< \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) then \(-\sqrt{\lambda }\gamma> -\sqrt{\lambda_{1}(\gamma)}\gamma\). Now, \(\frac{\mu ^{2}}{\gamma^{2}} < \overline{\lambda}_{1}(\mu)\) for \(-\sqrt{\lambda _{1}(\gamma)}\gamma< \mu< 0\) since \(\frac{\mu^{2}}{\gamma^{2}}\) is a convex function, while \(\overline{\lambda}_{1}(\mu)\) is a concave function (see Fig. 9). But \(\lambda= \frac{ ( -\sqrt{\lambda }\gamma )^{2}}{\gamma^{2}}\). Hence, taking \(\mu= -\sqrt{\lambda }\gamma\), we obtain

and by (25) we have \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > 0\). A similar argument for the case when \(\lambda> \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) gives that \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\). Note that \(\lambda= \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\) implies that we have equality in (26), and thus, \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) = 0\). □

Now, for fixed λ and γ, we consider the eigenvalue problem

Notice that letting \(\tilde{\delta} = \delta- \sqrt{\lambda}\gamma \) implies that (27) becomes

and the principal eigenvalue \(\tilde{\delta}_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) is nothing but the x-coordinate of the intersection of the curves \(\bar {\lambda}_{1}(\tilde{\delta})\) and \(\tilde{\delta} + (\lambda + \sqrt{\lambda}\gamma )\) (see Fig. 10). Hence the principal eigenvalue \(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) of (27) exists and is given by

We next establish a relationship between the signs of \(\delta _{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) and \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)\) in the following result.

Lemma 5

\(\operatorname{sign}(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma)) = \operatorname{sign}(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma))\).

Proof

Let \(\phi_{1}\) and \(\phi_{2}\) be corresponding positive eigenfunctions in (27) and (28). Then, by Green’s second identity, we have that

which implies

Now, it immediately follows that \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) = 0\) if and only if \(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) = 0\), and if \(\delta _{1}(\lambda, \gamma) \neq0\), then we have

Thus, if \(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > 0\), then we must have that \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > \delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > 0\), and if \(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\), then \(\sigma_{1}(\lambda, \gamma ) < \delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) < 0\). Hence the result. □

Finally, combining Lemmas 4 and 5, the following lemma immediately follows.

Lemma 6

If \(\lambda< \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), then \(\delta_{1}(\lambda, \gamma) > 0\). Also, if \(\lambda> \lambda_{1}(\gamma)\), then \(\delta_{1}(\lambda , \gamma) < 0\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Goddard II, J., Morris, Q.A., Robinson, S.B. et al. An exact bifurcation diagram for a reaction–diffusion equation arising in population dynamics. Bound Value Probl 2018, 170 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-1090-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-1090-z