Abstract

Background

Despite the known associations between zinc levels and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia and related cognitive impairment, the underlying neuropathological links remain poorly understood. We tested the hypothesis that serum zinc level is associated with cerebral beta-amyloid protein (Aβ) deposition. Additionally, we explored associations between serum zinc levels and other AD pathologies [i.e., tau deposition and AD-signature cerebral glucose metabolism (AD-CM)] and white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), which are measures of cerebrovascular injury.

Methods

A total of 241 cognitively normal older adults between 55 and 90 years of age were enrolled. All the participants underwent comprehensive clinical assessments, serum zinc level measurement, and multimodal brain imaging, including Pittsburgh compound B-positron emission tomography (PET), AV-1451 PET, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, and magnetic resonance imaging. Zinc levels were stratified into three categories: < 80 μg/dL (low), 80 to 90 μg/dL (medium), and > 90 μg/dL (high).

Results

A low serum zinc level was significantly associated with increased Aβ retention. In addition, apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (APOE4) status moderated the association: the relationship between low zinc level and Aβ retention was significant only in APOE4 carriers. Although a low zinc level appeared to reduce AD-CM, the relationship became insignificant on sensitivity analysis including only individuals with no nutritional deficiency. The serum zinc level was associated with neither tau deposition nor the WMH volume.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that decreased serum zinc levels are associated with elevation of brain amyloid deposition. In terms of AD prevention, more attention needs to be paid to the role of zinc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Zinc is the most abundant trace metal in the brain [1]. Disruption of zinc homeostasis may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1,2,3]. Preclinical studies using an AD mouse model revealed that brain zinc bound to beta-amyloid protein (Aβ) plaques and that the levels remained high therein [4] and that zinc treatment increased amyloid precursor protein (APP) expression, enhanced amyloidogenic APP cleavage and Aβ deposition, and impaired spatial learning and memory [5]. A postmortem human brain study revealed that brain zinc accumulation was a prominent feature of AD, linked to brain Aβ accumulation and dementia severity [3]. Serum zinc concentrations from 12 sisters who died in the Nun Study, determined approximately 1 year before death, also showed inverse correlations with senile plaque counts in the brain [6]. Additionally, many human studies have found that serum zinc levels were decreased in AD dementia compared to healthy controls [7,8,9,10,11]. Low serum zinc levels were also associated with rapid progression of AD dementia [2] and poorer cognitive performance [12].

Despite the associations between serum zinc and clinical AD dementia as well as the associations between zinc and Aβ deposition observed in preclinical and postmortem studies, as of yet, no study has investigated the relationship between serum zinc levels and Aβ deposition or other AD-related brain pathologies in the living human brain.

Thus, we aimed to test the hypothesis that serum zinc level is associated with brain Aβ deposition in cognitively normal (CN) older adults. Additionally, we explored the associations between serum zinc level and other AD pathologies (i.e., tau deposition and AD-signature neurodegeneration) and white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), which are measures of cerebrovascular injury.

Methods

Participants

This study was part of the Korean Brain Aging Study for Early Diagnosis and Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease (KBASE), which is an ongoing prospective cohort study [13]. As of February 2017, a total of 241 CN older adults between 55 and 90 years of age were enrolled. The CN group consisted of participants with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [14] score of 0 and no diagnosis of mild cognitive disorder or dementia. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a major psychiatric illness, (2) a significant neurological (e.g., cerebrovascular) disease or any medical condition that could affect mental function. (3) contra-indications for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (e.g., a pacemaker or claustrophobia), (4) illiteracy, (5) the presence of significant visual/hearing difficulties and/or severe communication or behavioral problems that would render clinical examinations or brain scans difficult, and (6) use of an investigational drug. Exclusion criteria were sought by research clinicians who examined laboratory data, MRI results, clinical data collected by trained nurses during systematic interviews of participants, and reliable informants to whom we spoke during screening. More detailed information on recruitment was presented in our previous report [13].

Clinical assessments

All participants underwent comprehensive clinical and neuropsychological assessments administered by trained psychiatrists and neuropsychologists based on the KBASE assessment protocol [13]. This incorporates the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) neuropsychological battery [15,16,17]. Vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, transient ischemic attack, and stroke) were assessed based on data collected by trained nurses during systematic interviews of participants and their family members. A vascular risk score (VRS) was calculated based on the number of vascular risk factors present and reported as a percentage [18]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms [19, 20]. Annual income was evaluated and categorized into three groups [below the minimum cost of living (MCL), more than the MCL but below twice the MCL, and twice the MCL or more] (http://www.law.go.kr). The MCL was determined according to the administrative data published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, in November 2012. The MCL was 572,168 Korean Won (KRW) [equivalent to 507.9 US dollars (USD)] per month for single-person households with an additional 286,840 KRW (equivalent to 254.6 USD) per month for each additional housemate. To ensure that the information was accurate, reliable informants were also interviewed.

Measurement of serum zinc levels and other blood biomarkers

After an overnight fasting, blood samples were obtained via venipuncture in the morning (8–9 a.m.). We measured serum zinc and copper levels using an inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer (model 820-MS; Bruker, Australia). We also measured serum copper, calcium, iron, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin levels because they could confound the relationship between zinc levels and brain changes [21]. We measured blood hemoglobin, albumin, and total cholesterol levels to evaluate anemia and nutritional deficiency. Calcium, iron, albumin, and total cholesterol levels were measured using a colorimetric method (ADVIA 1800 Auto analyzer, Siemens, USA). Transferrin and ceruloplasmin were measured employing immunoturbidimetric assays (Cobas Integra 800, Roche Diagnostics). Albumin levels were automatically determined (Advia 1800; Siemens, USA). Hemoglobin levels were determined by flow cytometry (Advia 2120i; Siemens, USA). Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood and apolipoprotein E (apoE) genotyping performed as previously described [22]. ApoE ε4 allele (APOE4) positivity was defined as the presence of at least one ε4 allele.

Measurement of cerebral Aβ deposition

All participants underwent contemporaneous three-dimensional (3D) [11C] Pittsburgh compound B (PiB)-positron emission tomography (PET) and 3D T1-weighted MRI scanning using a 3.0-T Biograph mMR (PET-MR) platform (Siemens, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. The PiB-PET imaging acquisition and preprocessing details were described previously [23]. An automatic anatomical labeling algorithm and a region-combining method [24] were applied to determine regions of interest (ROIs) for characterization of PiB retention levels in the frontal, lateral parietal, posterior cingulate-precuneus, and lateral temporal regions. Standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) values for each ROI were calculated by dividing the mean value for all voxels within each ROI by the mean cerebellar uptake value in the same image. A global cortical ROI consisting of the four ROIs was defined, and a global Aβ retention value was generated by dividing the mean value for all voxels of the global cortical ROI by the mean cerebellar uptake value in the same image [24, 25].

Measurement of cerebral tau deposition

A subset of subjects (n = 58) underwent [18F] AV-1451 PET scans using a Biograph True Point 40 PET/CT platform (Siemens, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Although all the other neuroimaging scans were performed during the baseline visit, AV-1451 PET imaging was performed at an average of 2.55 (standard deviation = 0.26) years after that visit. The details of AV-1451 PET imaging acquisition and preprocessing have been described previously [23]. To estimate cerebral tau deposition, we quantified the AV-1541 SUVR of an a priori ROI of the “AD-signature region” of tau accumulation, which was a size-weighted average of the partial volume-corrected uptakes by the entorhinal, amygdala, parahippocampal, fusiform, inferior temporal, and middle temporal ROIs, in line with a published method [26]. The AV-1451 SUVR of this ROI served as the outcome variable for cerebral tau deposition.

Measurement of AD-signature neurodegeneration

All participants underwent [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET imaging using the above-described PET-MR platform; the details of FDG-PET image acquisition and preprocessing have been described previously [23]. AD-signature FDG ROIs that are sensitive to the changes associated with AD, such as the angular gyri, posterior cingulate cortex, and inferior temporal gyri [27], were determined. AD-signature cerebral glucose metabolism (AD-CM) was defined as the voxel-weighted mean SUVR extracted from the AD-signature FDG ROIs.

Measurement of WMH

All participants underwent MRI including T1-weighted images and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging using the abovementioned 3.0-T PET-MR platform. WMH volume was measured using a validated automatic procedure that has been previously reported [28]. Briefly, the procedure consists of 11 steps: spatial co-registration of T1 and FLAIR images, fusion of T1 and FLAIR images, segmentation of T1 images, acquisition of transformation parameters, deformation and acquisition of the white matter mask, acquisition of FLAIR within the white matter mask, intensity normalization of the masked FLAIR, nomination of candidate WMH with a designated threshold, creation of a junction map, and elimination of the junction. There were two modifications in the current processing procedure relative to that used in the original study: (a) an optimal threshold of 70 was applied, as it was more suitable for our data than the threshold of 65 that was used in the original study; and, (b) given that individuals with acute cerebral infarcts were not enrolled in our sample, we did not use diffusion-weighted imaging in the current automated procedure. Using the final WMH candidate image, WMH volume was extracted in the native space in each subject.

Statistical analysis

To examine the relationships between the serum zinc level and neuroimaging biomarkers, multiple linear regression analyses were performed as appropriate. The zinc level, which was an independent variable in each analysis, was entered as a stratified categorical variable (three categories: low < 80 μg/dL, medium 80 to 90 μg/dL, and high > 90 μg/dL) by reference to the criteria for zinc deficiency (deficient < 60 μg/dL, marginal deficiency ≥60 to < 80 μg/dL, and normal ≥80 μg/dL) [29]. On statistical analysis, deficiency and marginal deficiency were combined into the low category, because only one participant exhibited a deficiency. Within the normal zinc range, the median value (i.e., 90 μg/dL) served as the cutoff between the low-normal (medium) and high-normal (high) levels. To analyze the associations between serum zinc levels and neuroimaging biomarkers, two models were used for stepwise control of potential confounders. The first model did not include any covariate and the second model included all potential covariates (i.e., age, sex, educational level, APOE4 positivity status, the VRS, the BMI, the GDS score, annual income status, and albumin, copper, calcium, iron, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin levels) that might confound the relationship between the zinc level and brain change [21]. On multiple linear regression analyses, global Aβ retention and WMH values were subjected to natural log-transformations to achieve normal distributions. In all analyses, a high zinc level served as the reference (i.e., high zinc vs. medium zinc, or high zinc vs. low zinc). Sensitivity analyses were performed for the participants with no nutritional deficiencies (i.e., serum albumin < 3.5 g/dL and total cholesterol < 150 mg/dL) [30, 31] to reduce the influence of a general nutritional deficiency on the association between serum zinc level and brain changes. To explore the influence of age, sex, APOE4 positivity, VRS, and the copper, calcium, and iron levels on the associations between serum zinc levels and the biomarkers that were significant in the analyses described above, the regression analyses were repeated but now including two-way interaction terms between serum zinc levels and the biomarkers as additional independent variables. All statistical analyses were performed with the aid of IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

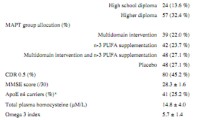

The demographic and clinical characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1. Of the total of 241 participants, 70 had low zinc levels, 80 had medium zinc levels, and 91 had high zinc levels.

Association of serum zinc level with cerebral Aβ deposition

Low serum zinc was associated with significantly increased global Aβ retention compared to the high serum zinc (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Additional analyses for the association between serum zinc and regional Aβ retention showed similar results (Table 3), indicating no regional specificity of the association. Sensitivity analysis of participants with no nutritional deficiencies yielded similar results (Table 4).

Box plots displaying stratified serum zinc levels and global Aβ retentions in cognitively normal older participants. A Overall and B, C by subgroup [B APOE4-negative and C APOE4-positive]. Footnotes: Error bars indicate standard errors. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed after adjusting for all confounding factors

Association of the zinc level with other brain pathologies

No differences in terms of tau deposition or WMH were observed between the serum zinc categories (Tables 2 and 4). A reduced AD-CM was related to a low serum zinc level (Table 2), but the relationship became insignificant on sensitivity analysis of only individuals with no nutritional deficiency (Table 4).

Moderation of the association between the serum zinc level and cerebral Aβ deposition

The serum zinc × APOE4 positivity interaction was significant in terms of Aβ retention, indicating that APOE4 positivity moderates the association between the serum zinc level and cerebral Aβ deposition (Table 5). Further subgroup analyses showed that low serum zinc was significantly associated with higher Aβ deposition in the APOE4-positive but not APOE4-negative subgroup (Table 6 and Fig. 1). The interactions between the serum zinc level and other variables, including sex, the VRS, and copper, calcium, and iron levels, were not significant (Table 5).

Discussion

In older individuals lacking cognitive impairment, low serum zinc was associated with increased in vivo global Aβ retention, supporting the hypothesis that low serum zinc is associated with high brain amyloid deposition, in line with the inverse correlation between serum zinc levels determined about 1 year before death and the postmortem senile plaque counts in 12 individuals of the Nun Study [6]. Many clinical studies have also reported associations between low serum zinc levels and clinical AD dementia or poor cognitive performance.

Regarding the mechanism underlying the relationship between lower serum zinc and higher brain Aβ deposition, lower serum zinc may reflect sequestration of zinc in the brain due to its binding to Aβ and depletion in other body compartments such as blood [6, 32]. Zinc was bound to Aβ plaques and remained high in such plaques in an AD mouse model [4], and senile plaques were markedly enriched with zinc in the human brain [33, 34]. A preclinical study also demonstrated that human Aβ peptide specifically bound zinc [35]. Although the consequence of zinc sequestration by Aβ peptides and its impact on AD pathogenesis is not clearly understood yet, recent evidences suggest that decreased zinc levels in the synaptic cleft can alter glutamatergic excitotoxic neurotransmission and promote synaptic failure and neuronal death [32, 35,36,37]. Alternatively, lower serum zinc level caused by dietary zinc deficiency might result in more Aβ deposition, as has been demonstrated in an animal model study [38]. However, this possibility seems not so high given that the sensitivity analysis for individuals with no nutritional deficiency revealed similar results.

We also found that APOE4 status moderated the relationship between the serum zinc level and amyloid deposition. We found a significant negative association between the zinc level and Aβ deposition in participants with APOE4, but not those without APOE4. This may reflect associative interactions between zinc, the apoE4 isoform, and Aβ deposition [39]. ApoE4 binds to Aβ and facilitates Aβ fibrillation more easily than do the apoE2 and apoE3 isoforms [40, 41]. Additionally, as the sulfhydryl groups of cysteine residues are responsible for zinc binding [42, 43], the arginine substitutions in apoE4 restrict its ability to control zinc homeostasis and zinc-dependent molecular changes in the AD brain [44].

We additionally found a significant association between a low serum zinc level and decreased AD-CM. In contrast, we found no association between the serum zinc level and either tau deposition or WMH, indicating that zinc-related hypometabolism is possibly not mediated by brain tau deposition or cerebrovascular injury. The interaction of zinc with Aβ within Aβ plaques in the AD brain may trigger a neuronal zinc imbalance at the glutamatergic synapse level, further exacerbating synaptic dysfunction and the associated cerebral hypometabolism [1, 11, 45, 46]. Another possible explanation for the association between a low serum zinc level and brain hypometabolism is that the association may be cofounded by nutritional status; a nutritional deficiency is associated with both low serum zinc levels and reduced brain metabolism [47]. Sensitivity analysis of only participants lacking nutritional deficiencies revealed that the association between the serum zinc level and AD-CM was no longer significant, supporting the above explanation.

Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show an association between the serum zinc level and brain Aβ accumulation in living humans. Even after controlling for all potential confounders, the findings did not change. The results were confirmed by sensitivity analysis performed after excluding participants with nutritional deficiencies. However, our study had a couple of limitations. First, as this was a cross-sectional work, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Long-term prospective studies are needed. Second, tau PET was performed at an average of 2.55 years (standard deviation 0.26 years) after the baseline visit; the other neuroimaging scans were performed at baseline. This temporal gap may have influenced the association between zinc and tau. When we controlled for the temporal gap as an additional covariate, however, the results did not change. In addition, only a subset of participants (n = 58) underwent tau PET, whereas all participants underwent all other imaging modalities. The lower tau PET sample size may have decreased the statistical power and thus contributed to the null result for the relationship between zinc level and tau deposition. A study with a larger sample size is required.

Conclusion

The present findings suggest that a decreased serum zinc level is associated with elevation of brain amyloid deposition, particularly in APOE4 carriers. In terms of AD prevention, more attention needs to be paid to the role of zinc.

Availability of data and materials

The data of the current study are not freely accessible because the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital prohibits public data-sharing for privacy reasons. However, the data may be available from the independent data-sharing committee of the KBASE research group on reasonable request, after approval by the IRB. Requests for data access can be submitted to the administrative coordinator of the KBASE group by e-mail (kbasecohort@gmail.com); the coordinator is independent of the authors.

Change history

16 February 2022

Figure 1 in the article has been updated with a high image resolution.

References

Watt NT, Whitehouse IJ, Hooper NM. The role of zinc in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2011:971021.

Dong J, Robertson JD, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Serum zinc in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:443–50.

Religa D, Strozyk D, Cherny RA, Volitakis I, Haroutunian V, Winblad B, et al. Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:69–75.

James SA, Churches QI, de Jonge MD, Birchall IE, Streltsov V, McColl G, et al. Iron, copper, and zinc concentration in Abeta plaques in the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease correlates with metal levels in the surrounding neuropil. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:629–37.

Wang CY, Wang T, Zheng W, Zhao BL, Danscher G, Chen YH, et al. Zinc overload enhances APP cleavage and Abeta deposition in the Alzheimer mouse brain. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15349.

Tully CL, Snowdon DA, Markesbery WR. Serum zinc, senile plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles: findings from the Nun study. Neuroreport. 1995;6:2105–8.

Brewer GJ, Kanzer SH, Zimmerman EA, Molho ES, Celmins DF, Heckman SM, et al. Subclinical zinc deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2010;25:572–5.

Baum L, Chan IH, Cheung SK, Goggins WB, Mok V, Lam L, et al. Serum zinc is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease and serum arsenic correlates positively with cognitive ability. Biometals. 2010;23:173–9.

Li DD, Zhang W, Wang ZY, Zhao P. Serum copper, zinc, and iron levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:300.

Wang ZX, Tan L, Wang HF, Ma J, Liu J, Tan MS, et al. Serum iron, zinc, and copper levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a replication study and meta-analyses. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:565–81.

Ventriglia M, Brewer GJ, Simonelli I, Mariani S, Siotto M, Bucossi S, et al. Zinc in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:75–87.

Markiewicz-Zukowska R, Gutowska A, Borawska MH. Serum zinc concentrations correlate with mental and physical status of nursing home residents. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117257.

Byun MS, Yi D, Lee JH, Choe YM, Sohn BK, Lee JY, et al. Korean brain aging study for the early diagnosis and prediction of Alzheimer’s disease: methodology and baseline sample characteristics. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14:851–63.

Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4.

Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part I. clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–65.

Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean version of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease assessment packet (CERAD-K): clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P47–53.

Lee DY, Lee KU, Lee JH, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim SY, et al. A normative study of the CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery in the Korean elderly. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:72–81.

DeCarli C, Mungas D, Harvey D, Reed B, Weiner M, Chui H, et al. Memory impairment, but not cerebrovascular disease, predicts progression of MCI to dementia. Neurology. 2004;63:220–7.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49.

Kim JY, Park JH, Lee JJ, Huh Y, Lee SB, Han SK, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of the geriatric depression scale: reliability, validity, and factor structure. Psychiatry Investig. 2008;5:232–8.

Armstrong C, Leong W, Lees GJ. Comparative effects of metal chelating agents on the neuronal cytotoxicity induced by copper (cu+2), iron (Fe+3) and zinc in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2001;892:51–62.

Wenham PR, Price WH, Blandell G. Apolipoprotein E genotyping by one-stage PCR. Lancet. 1991;337:1158–9.

Park JC, Han SH, Yi D, Byun MS, Lee JH, Jang S, et al. Plasma tau/amyloid-beta1-42 ratio predicts brain tau deposition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2019;142:771–86.

Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Yu M, Lee W, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6820–5.

Choe YM, Sohn BK, Choi HJ, Byun MS, Seo EH, Han JY, et al. Association of homocysteine with hippocampal volume independent of cerebral amyloid and vascular burden. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1519–25.

Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:205–16.

Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Rocca WA, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Age-specific population frequencies of cerebral beta-amyloidosis and neurodegeneration among people with normal cognitive function aged 50-89 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:997–1005.

Tsai JZ, Peng SJ, Chen YW, Wang KW, Li CH, Wang JY, et al. Automated segmentation and quantification of white matter hyperintensities in acute ischemic stroke patients with cerebral infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104011.

Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, Saita M, Miyagami T, Takahashi Y, Hisaoka T, et al. Serum zinc concentrations and characteristics of zinc deficiency/marginal deficiency among Japanese subjects. J Gen Fam Med. 2020;21:248–55.

Kuzuya M, Kanda S, Koike T, Suzuki Y, Satake S, Iguchi A. Evaluation of Mini-nutritional assessment for Japanese frail elderly. Nutrition. 2005;21:498–503.

Omran ML, Morley JE. Assessment of protein energy malnutrition in older persons, part II: laboratory evaluation. Nutrition. 2000;16:131–40.

Sensi SL, Granzotto A, Siotto M, Squitti R. Copper and zinc dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39:1049–63.

Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:47–52.

Cherny RA, Legg JT, McLean CA, Fairlie DP, Huang X, Atwood CS, et al. Aqueous dissolution of Alzheimer’s disease Abeta amyloid deposits by biometal depletion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23223–8.

Bush AI, Pettingell WH. Multhaup G, d Paradis M, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Tanzi RE: rapid induction of Alzheimer a beta amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265:1464–7.

Bush AI, Tanzi RE. Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease based on the metal hypothesis. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:421–32.

Sensi SL, Paoletti P, Bush AI, Sekler I. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:780–91.

Stoltenberg M, Bush AI, Bach G, Smidt K, Larsen A, Rungby J, et al. Amyloid plaques arise from zinc-enriched cortical layers in APP/PS1 transgenic mice and are paradoxically enlarged with dietary zinc deficiency. Neuroscience. 2007;150:357–69.

Oh SB, Kim JA, Park S, Lee JY. Associative interactions among zinc, apolipoprotein E, and amyloid-beta in the amyloid pathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21.

Wisniewski T, Castano EM, Golabek A, Vogel T, Frangione B. Acceleration of Alzheimer’s fibril formation by apolipoprotein E in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1030–5.

Sanan DA, Weisgraber KH, Russell SJ, Mahley RW, Huang D, Saunders A, et al. Apolipoprotein E associates with beta amyloid peptide of Alzheimer’s disease to form novel monofibrils. Isoform apoE4 associates more efficiently than apoE3. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:860–9.

Borden KL. RING fingers and B-boxes: zinc-binding protein-protein interaction domains. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:351–8.

Klug A, Schwabe JW. Protein motifs 5. Zinc fingers FASEB J. 1995;9:597–604.

Moir RD, Atwood CS, Romano DM, Laurans MH, Huang X, Bush AI, et al. Differential effects of apolipoprotein E isoforms on metal-induced aggregation of a beta using physiological concentrations. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4595–603.

Capasso M, Jeng JM, Malavolta M, Mocchegiani E, Sensi SL. Zinc dyshomeostasis: a key modulator of neuronal injury. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:93–108 discussion 209-115.

Kato T, Inui Y, Nakamura A, Ito K. Brain fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET in dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;30:73–84.

Delvenne V, Lotstra F, Goldman S, Biver F, De Maertelaer V, Appelboom-Fondu J, et al. Brain hypometabolism of glucose in anorexia nervosa: a PET scan study. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:161–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the KBASE Research Group for their contribution. Members of the KBASE Research Group are listed elsewhere (http://kbase.kr). We sincerely thank the subjects for their participation in this study. The precursor of [18F] AV-1451 was provided by AVID Radiopharmaceuticals.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (grant No: NRF-2014M3C7A1046042 & NRF-2020R1G1A1099652), a grant from the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI18C0630 & HI19C0149), a grant from the Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea (No. 3020200030) and a grant from the National Institute of Aging, United States of America (U01AG072177). The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JWK and DYL conceived and designed the study. MSB, DY, JHL, MJK, GJ, J-YL, KMK, C-HS, Y-SL, YKK, and DYL were involved in the acquisition or analysis and interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. JWK, MSB, DY, JHL, and DYL were major contributors in writing the manuscript and critically revising the manuscript for intellectual content. DYL served as the principal investigator and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) (C-1401-027-547) and Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University (SMG-SNU) Boramae Medical Center (26–2015-60), Seoul, South Korea, and was conducted in accordance with the recommendations in the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The subjects or their legal representatives gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Supplementary material including authors list for the KBASE group.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.W., Byun, M.S., Yi, D. et al. Serum zinc levels and in vivo beta-amyloid deposition in the human brain. Alz Res Therapy 13, 190 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00931-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00931-3