Abstract

Background

Vascular endothelial dysfunction induced by hyperglycemia and elevated insulin resistance is a potent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and likely contributes to multiple chronic disease complications associated with aging. The aim of this study was to systematically review and quantify the effects of exercise on endothelial function (EF) in type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

Five electronic databases were searched (until June 2017) for studies that met the following criteria: (i) randomized controlled trials; (ii) T2D aged ≥ 18 years; (iii) measured EF by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD); (iv) structured and supervised exercise intervention for ≥ 8 weeks.

Results

Thirteen cohorts, selected from eight studies (306 patients, average age 59 years), met the inclusion criteria. Exercise training significantly increased FMD (mean ES = 0.41, 95% CI 0.21–0.62, P < 0.001). Low to moderate intensity subgroups and aerobic exercise (AE) subgroups significantly increased FMD more than moderate to high intensity subgroups and combined AE and resistance exercise subgroups respectively (P < 0.01, P < 0.05). The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) assessments reported that quality of evidence for all outcomes was moderate except shear rate showing low. Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias for all outcomes.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that in patients with T2D, lower intensity exercise has physiological meaningful effects on EF, in support of the emerging concept that the lower efforts of exercise are not necessarily less cardioprotective than higher intensity training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. According to American Heart Association, CVD in older adults with T2D accounts for 84% of the deaths [2]. Vascular endothelial dysfunction is related to elevated blood glucose level and insulin resistance and is a major cause in the pathological progression towards CVD [3, 4]. Endothelial dysfunction is considered a precursor of atherosclerosis and CVD [5] because the vascular endothelium plays an important physiological role in vascular homeostasis [6]. In most clinical and physiological settings, the direct physiological or biochemical effects signaling within the endothelium are more associated with endothelial dysfunction than smooth muscle dysfunction per se [7]. Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells release and respond to the internally generated substances including nitric oxide (NO) to regulate the vascular relaxation and tone [8].

Regular physical activity has been recommended as an effective treatment together with medications and dietary control to improve vascular endothelial function (EF) in T2D. Skeletal muscle contraction during physical activity increases local blood flow and cardiac output, which results in increased shear stress on vascular endothelium and increased NO production [9]. From a review of six previous studies, Way et al. [10] concluded that exercise training did not result in a significant effect on EF in T2D , whereas Montero et al. [11] observed that exercise training in four studies improved EF in T2D. There were mixed results, potentially in part, because of the small number of participants in which EF was evaluated by brachial artery FMD, the gold standard measure of EF [12].

Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of exercise training on EF measured by brachial artery FMD in adults with T2D by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis. In doing this, we carefully examined the specifics of the exercise training regimens (such as intensity, modality, duration, and frequency of exercise) and the reported body mass index (BMI) in order to provide more evidence for designing exercise programs for T2D patients at risk of CVD.

Methods

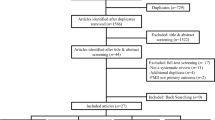

This current systematic review followed the strategy of The PRISMA Statement [13].

Data sources

Five electronic databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed, SportDiscus, and Web of Science) were searched for eligible studies published in English from the earliest date available to June 2017. The following keywords were used for searches: ‘exercise or training or physical activity’, ‘flow mediated dilation’, and ‘type 2 diabetes’. Manual searches of reference lists were conducted to ensure all relevant studies were captured. Two reviewers (Lee JH and Lee RD) independently searched all of the articles and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts searched. Disagreements about the inclusion and exclusion were resolved by another reviewer (MH, Hwang). When the information was not clear, the full text papers of the studies were obtained for review. Corresponding authors of potentially eligible studies were contacted if studies reported data for which it was impossible to discriminate.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria for eligible studies were as follows: (i) randomized controlled trials; (ii) adult humans aged ≥ 18 years who have T2D which was defined by the World Health Organization and the American Diabetes Association’s criterion of fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l or 126 mg/dl; (iii) studies that measured EF by brachial artery FMD; (iv) structured and supervised exercise intervention for ≥ 8 weeks. Studies were excluded if T2D patients have a neurological complication, diabetic neuropathy. Duplicate studies or sub-studies of included trials were also excluded from the analysis. Trials including dietary supplements or caloric restriction were excluded to focus on the effects of exercise alone.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (Lee JH and Lee RD) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the PRISMA recommendations [13]. The quality assessment consisted of six items: (i) appropriate generation of random allocation sequence; (ii) concealment of the allocation sequence; (iii) blinding of the assessment and collection outcomes; (iv) proportion of participants lost to follow-up; (v) complete outcome data; (vi) the intention-to-treat principle [13]. Where reviewers disagreed, specific criteria were discussed with a third reviewer (Hwang MH) until consensus was reached. In addition, the overall quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [14]. Based on this assessment, the intervention was graded accordingly: ‘high quality’—we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; ‘moderate quality’—we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different; ‘low quality’—our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; ‘very low quality’—we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect [15].

Data extraction

Data were extracted from all selected studies by two independent reviewers to record the detailed information in terms of subject characteristics, study methods, interventions, outcomes, and adverse events. We used means and standard deviation (SD), but where standard errors or 95% confidence interval (CI) were provided, they were converted to SD. Corresponding authors were contacted for detailed information where required.

In terms of population characteristics, age, gender, BMI, number of participants, complications, and duration of T2D of participants were recorded to compare the similarity of participants between trials. The primary outcomes were FMD including shear rate and baseline diameter, and secondary outcome was BMI. Brachial artery was only selected instead of femoral or popliteal artery for the measurement of FMD because it was more possible to compare across multiple studies from the brachial arm measurements and the assessment of brachial EF plays a role in predicting CVD and atherosclerosis [16]. Regarding intervention, we recorded total duration, frequency (days per week), intensity, session duration, type and order of exercise, names of exercise machine or tool, supervisors, and places of intervention to compare the similarity of training methods between trials. The median values were used for calculation if the studies reported a range of data (e.g. 16, 15–17 of repetitions). Detailed interventions about control groups (CON) and any additional supplements were recorded. Measurement technique and region were also extracted.

Data analysis

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochran Q statistic [17] and the I2 test [18]. I2 ranges from 0 to 100%: a value < 25% indicates low risk of heterogeneity, 25–75% indicates moderate risk of heterogeneity, and > 75% indicates high risk of heterogeneity. In each study, the effect size (ES) for the intervention was calculated by the difference between the means of the post-measurement and pre-measurement at the end of the intervention using Hedges g. Separate meta-analyses of trials with FMD, shear rate, baseline diameter, and BMI were performed to generate the mean ES and 95% CI. ESs were classified according to Cohen’s definition (1988), where 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large [19]. We used a fixed-effects model when homogeneity was verified or a random-effects model when heterogeneity was shown by the Q statistic [18]. Where multiple intervention groups were included in one study, we split the shared group into two or more groups with smaller sample size [20]. Publication bias was assessed using the Egger’s regression test [21]. To evaluate whether an individual cohort had undue influence on the overall meta-analysis result, we performed sensitivity analyses in all four outcomes by omitting one of the trials at a time and determining whether statistical conclusion remained the same. All calculations were conducted with SPSS version 20, Microsoft Excel 2016, and STATA version 14.2.

Subgroup analyses were performed where sufficient numbers of trials existed in subgroups to identify potential factors influencing the effect of exercise on outcomes and accounting for the heterogeneity between studies: (i) age < 60 versus age ≥ 60; (ii) low baseline BMI levels (< 30 kg/m2) versus high baseline BMI levels (≥ 30 kg/m2); (iii) low baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (6.5–7.5%) versus high baseline HbA1c levels (> 7.5%); (iv) low baseline FMD levels (≤ 4.8%) versus high baseline FMD levels (> 4.8%); (v) AE versus combined AE and RE; (vi) low to moderate intensity versus moderate to high intensity; (vii) 8 weeks versus 12 weeks or more; (viii) less than 60-min versus 60-min or more. Random effects meta-analysis regression was conducted to compare the effect estimates (effect size) in different subgroups by considering the meta-analysis results from each subgroup separately. To interpret the results of subgroup analyses, P value (P < 0.05) between study variation was considered for the statistical difference between subgroups.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The search resulted in 7870 potential studies (Fig. 1). From the titles and abstracts, 7842 studies were excluded based on the criteria, and then 27 full text studies were reviewed. Of these, 19 articles were excluded; two articles were duplicate [22, 23], one measured FMD of popliteal artery [24], two had patients with different kinds of diseases as well as T2D in the groups [25, 26], three had T2D patients with peripheral arterial disease or diabetic peripheral neuropathy [27,28,29], two did not provide precise data [30, 31], two additionally treated dietary control for weight loss [32, 33], three involved unstructured or unsupervised exercise intervention [34,35,36], and four were just abstracts with incomplete data [37,38,39,40]. Four exercise groups (EX) with additional interventions were included after discussing because there was no difference in the effect of interventions on FMD, our major outcome, between the CON and experimental groups: (i) exercise in the hypoxic environment (16.5% O2, 2000 m) [41]; (ii) endothelin (ET) receptor blockade or a placebo [42]; (iii) walking meditation [43]. One AE trial which recorded the time, frequency, and intensity of exercise by a multi-record accelerometer were also included because the subjects visited the laboratory every 1 or 2 weeks [44]. Moreover, two CON including AE on treadmill [43] and combined AE and RE in the normoxic environment [41] were included in the EX. Eventually, we selected thirteen exercise trials in eight studies by consensus.

Participants

Table 1 shows the characteristics of all of the studies included. Articles were published from January 2010 [45] to June 2016 [43]. The sample size was 316. Of these, 10 healthy participants in the CON [46] were excluded for our analysis. 306 participants completed their intervention (EX: 196, CON: 110, female%: 45%) ranging from 18 [42] to 112 [47] participants. The average age of the participants was 59 years (EX: 59 ± 7.2, CON: 58 ± 6.4). Other results from baseline measures were as follows: (i) BMI: 30.3 (EX: 30.0 ± 4.4, CON: 30.7 ± 3.6); (ii) HbA1c: 7.2% (EX: 7.4 ± 1.4, CON: 7.1 ± 1.2%); (iii) FMD: 5.5% (EX: 5.1 ± 3.5, CON: 5.9 ± 4.0).

Interventions

All interventions, except for one AE group [44] using a multi-record accelerometer, were supervised in research centers by a fitness coach, researchers, or physiotherapists. The mean training period was 12 weeks (minimum–maximum: 8 [41, 42, 46] to 26 [47] weeks). Mean session duration was 57-min (minimum–maximum: 30 [48] to 80 [41, 47] min). In most studies, training frequency was 3 days per week (with the exception of [45] and [44] where 3–5 and 5 days per week were completed respectively). Of thirteen trials, five conducted AE [43, 44, 48], seven conducted a combination of AE and RE [41, 42, 45,46,47], and one conducted RE [44].

AE trials expressed intensity as a percent of maximum heart rate (HRmax), hear rate reserve (HRR), peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) or metabolic equivalents (METs). Intensities ranged from low to moderate (50–70% of HRmax [43, 45], 60–65% of VO2peak [48], and 3.6–6.0 METs [44]) to moderate to high (60–90% of HRmax [47], 70–75% of HRR [41, 42, 46]). One interval training (INT) group of [48] performed at 80–85% of VO2peak for 1-min with 50–60% VO2peak for 4-min, which was included in the subgroup of moderate to high intensity. AE trials of [42, 46, 48] increased their intensity over the duration of the intervention, but [41] maintained their intensity and [44,45,46,47] were not known.

RE trials established their intensity by a percent of one-repetition maximum (1-RM) or 12-RM (a level which enables the participant to complete 12 repetitions). Intensities ranged from low (40–50% of 1-RM [44, 47]) to moderate (12-RM [42, 46]). Of these, four trials increased their intensity over the duration of the intervention [42, 44, 46] except for [47]. All RE trials were performed both on upper and lower body by using 6 [42, 46], 7 [47], or 10–15 [44] exercises. In [41, 45], we could not get detailed information about training, although we contacted two of the corresponding authors. Of seven combination of AE and RE, [41, 45, 47] conducted AE and RE separately and [42, 46] combined them as a circuit training. In the current study, the CON consisted of non-exercise [44, 45, 47, 48], exercise with a placebo [42], AE on treadmill [43], combined AE and RE in the normoxic environment [41], and exercise of healthy adults [46]. Of these, one healthy group [46] were excluded for our study and three remaining exercise trials [41,42,43] were included in the EX.

Measurements

All thirteen trials of eight studies measured FMD to assess brachial artery EF [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Five trials measured shear rate the area under the curve (AUC) [41, 42, 46], and [47] measured peak shear rate and [48] did shear rate at rest, which were excluded for our meta-analysis. Eleven trials measured baseline diameter [41,42,43, 45,46,47,48]. All trials measured FMD, shear rate, and baseline diameter of the brachial artery [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. There were quite differences of the inflation pressure for measuring FMD between studies: 50 mmHg above systolic blood pressure [43, 48], 200 mmHg [47], 220 mmHg [42, 45, 46], 250 mmHg [44], not known [41]. All duration of cuffing was 5-min. All trials measured BMI [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] but [44] was excluded for our meta-analysis because the study only provided the data at baseline.

Effect of exercise training

Flow mediated dilation

Exercise training in thirteen trials significantly increased brachial artery FMD (mean ES = 0.41, 95% CI 0.21–0.62, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The absolute increase of FMD was 1.7%. Univariate meta-regression did not show heterogeneity between studies (Q = 13.57, df = 12, P = 0.33, I2 = 11.6%). In subgroup analysis, subgroups with low to moderate intensity significantly increased FMD more than subgroups with moderate to high intensity after training (P < 0.01). AE subgroups significantly increased FMD more than combined AE and RE subgroups (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in effect between training for 8 weeks and ≥ 12 weeks (P = 0.25). Subgroups with low baseline BMI levels significantly increased FMD more than subgroups with high baseline BMI levels after training (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in effect between subgroups with age < 60 and ≥ 60 (P = 0.28), low baseline HbA1c levels and high levels (P = 0.25), and low baseline FMD levels and high levels (P = 0.68). We excluded frequency, session duration, and other variables for the multivariate analysis because equal classifying into subgroups was impossible.

Shear rate and baseline diameter

Exercise training in five trials did not result in a significant effect on shear rate AUC (mean ES = − 0.05, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.34, P = 0.82) (Fig. 3). Exercise training in eleven trials did not result in a significant effect on baseline diameter (mean ES = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.25 to 0.17, P = 0.72) (Fig. 4). Univariate meta-regression did not show heterogeneity between studies (shear rate, Q = 4.61, df = 4, P = 0.33, I2 = 13.1%) and (baseline diameter, Q = 1.69, df = 10, P = 0.998, I2 = 0%). Thus, we did not perform multivariate analysis with other variables.

Body mass index

Exercise training in eleven trials did not result in a significant effect on BMI (mean ES = − 0.13, 95% CI − 0.34 to 0.08, P = 0.22) (Fig. 5). Univariate meta-regression did not show heterogeneity between studies (Q = 3.15, df = 10, P = 0.98, I2 = 0%). Thus, we did not perform multivariate analysis with other variables.

Quality assessment and potential bias

In the quality assessment, 88% reported appropriate generation of a random allocation sequence (7 of 8), 13% presented concealment of the allocation sequence (1 of 8), 13% described blinding of the assessment and collection outcomes (1 of 8), 100% explained proportion of participants lost to follow-up (8 of 8), 100% exhibited complete outcome data (8 of 8), and 25% reported that the intention-to-treat principle was used for statistical analyses (2 of 8). The GRADE assessments are presented in Table 2, and quality of evidence for all outcomes was moderate except shear rate AUC showing low. Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias for FMD, shear rate, baseline diameter, and BMI (P = 0.21, P = 0.58, P = 0.86, and P = 0.55, respectively) (Fig. 6).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis reported that by excluding any of all cohorts from the meta-analysis the estimated effects will still be within the 95% CI of the mean ES in all four outcomes, suggesting the results of the meta-analysis will not significantly change after the removal of any one cohort. In terms of FMD, we conducted further sensitivity analysis by excluding two cohorts together, CON of [43] and AE group of [44] and the result did not yield a significantly different conclusion from the overall meta-analysis result (mean ES = 0.31, 95% CI 0.09–0.52, P < 0.01).

Adverse events

The presence or absence of adverse events was recorded in two of the nine studies. Two reported there were no adverse events [42, 45].

Discussion

The primary results of this meta-analysis study are that exercise training significantly increased brachial artery FMD by 1.7% in T2D patients with an average age of 59, but there was no change in shear rate AUC, baseline diameter, and BMI.

Regular exercise-induced improvement in vascular EF measured by FMD can be attributed in large part to the increase in endothelium-derived NO production and bioavailability [49]. NO is a major vasodilator, and plays an additional role in inhibiting atherosclerotic inflammatory process, oxidative stress [49], and smooth muscle cell proliferation [50]. In the current study, however, shear rate AUC remains unchanged after training, suggesting that medium- to long-term exercise training does not necessarily require altering only this physical stimulation for triggering FMD. Exercise also enhances antioxidant capacity by increased expression of the antioxidant enzymes and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase activity [51], resulting in the increase in NO bioavailability [52]. In addition to enhanced endothelial function, the improvement in vascular smooth muscle sensitivity to NO might play a partial role in increasing FMD through promoting vasodilation. T2D patients compared to healthy population may have lowered sensitivity to NO in vascular smooth muscle, and so pathways for vasodilation were degraded [53] because elevated blood glucose can decrease a response of smooth muscle cells by increasing oxidative stress [54]. However, previous human studies generally reported that exercise training does not result in effects on vascular smooth muscle sensitivity to NO [55,56,57], and these results may be due to that almost all human studies used a single dose of vasodilator nitroglycerine for assessing vascular smooth muscle function without considering the effects of dose–response changes [58] and that smooth muscle adaptation to exercise training might not be observed in vivo research [59]. Further studies using the elaborate assessment of smooth muscle function in humans is required.

Subgroups with low to moderate intensity training increased FMD more than moderate to high intensity subgroups in our study. Since shear stress is a potent factor for NO release, one might expect that moderate to high intensity training would have caused greater change in FMD than low to moderate intensity due to a greater rise in cardiac output and peripheral blood flow. This unexpected result may also suggest that increased NO production and availability in T2D patients do not solely depend on an increase in flow and/or shear stress. On the other hand, shear rate is determined by diameter because shear rate is calculated as blood flow velocity divided by diameter according to Pyke and Tschakovsky [60]. In our study, baseline brachial artery diameter remained unchanged after intervention, which may explain the reason why the amount of shear rate AUC change was insignificant even though blood flow velocity increased by exercise training. Therefore, there might have been a negligible difference in shear stress between low to moderate and moderate to high intensity training because variations of shear rate might be abated by unchanged diameter although high intensity training increased more blood flow velocity than low intensity training.

However, there is certainly a growing appreciation that the optimal exercise training program for many outcomes does not necessarily follow a dose–response relationship around the relative effort, and sometimes “more is not better” as once thought. There are also other factors to consider in the present set of studies measuring FMD in patients with diabetes. Firstly, the results we found may be due to that most subgroups with low to moderate intensity performed AE whereas most subgroups with moderate to high intensity did combination of AE and RE. Although there are few studies investigating effects of RE on EF comparing with AE in T2D patients, AE is more likely to improve EF than RE or combination AE and RE. Kwon et al. reported that AE significantly increased FMD in T2D patients but RE group also showed a tendency increasing FMD [44]. In the meta-analysis study by Ashor et al., FMD in adults was increased more by AE than RE or combination of AE and RE, but the two latter groups also increased FMD significantly [61]. RE has been considered increasing vascular stiffness because RE can induce endothelin-1 [62], a potent vasoconstrictor. Also, frequently elevated blood pressure during RE may alter the arterial structure or arterial load-bearing properties [63], which can attenuate the improvement in FMD by AE. However, Miyachi [63] reported, in his meta-analysis study, that high-intensity RE results in a significant increase in arterial stiffness, but combined AE and RE can prevent arteries from stiffening by high-intensity RE. Secondly, another possible description for more favorable effects of low to moderate intensity training subgroups on EF than moderate to high intensity training subgroups is that most subgroups with moderate to high intensity conducted both AE and traditional RE using a few specific skeletal muscles at once, resulting in an increase in local blood flow, in contrast to AE promoting blood circulation in whole body. However, in the current study, P value of the difference in effects between training with low to moderate intensity and moderate to high (P = 0.007) is greater than the one between AE and combination of AE and RE (P = 0.028), suggesting that training intensity may be more influential factor for improving vascular EF than training modality. Moreover, combination of AE and RE in our study mostly devotes more time on AE than RE. In particular, the combined exercise training subgroups have no high intensity RE (low: 40–50% of 1-RM [44, 47] to moderate: 12-RM [42, 46]) and moderate to high intensity AE (60% of HRmax [45], 60–90% of HRmax [47], 70–75% of HRR [41, 42, 46]). Thus, we can speculate that the reason why moderate to high intensity subgroups mostly conducting combination of AE and RE showed less increase in FMD is not just due to inclusion of RE to AE. Our results could provide opposing views against the previous studies placing more weight on the high intensity of AE in order to improve EF, and ultimately can suggest the possibility of low to moderate training as a new alternative therapeutic strategy for T2D patients.

However, in order to determine whether low to moderate intensity training can be an alternative treatment for T2D patients, further studies are required. Because original studies had a small sample size and this current study evaluated some even smaller subgroups of the original studies. Of 7870 potential studies, only eight studies were included for our meta-analysis by narrowing inclusion criteria, which could increase a risk of both bias and extrapolation of the results. On the other hand, heterogeneity between studies decreased due to the small number of well conducted studies in this field. Thus, one of the main positive aspects of this study was to uncover poor evidence on this field and assume a critical position.

Meanwhile, our results show that there was no significant difference in the effect of training duration on FMD between eight and twelve or more weeks, which indicates that vascular EF in T2D patients could be improved by exercise training for a relatively short period of time. Also, we can speculate that overweight or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) T2D patients need to have different exercise prescription from normal weight patients (< 30 kg/m2) because improvement of FMD in subgroups with low BMI levels (< 30 kg/m2) was higher compared to in subgroups with high BMI levels (≥ 30 kg/m2). Though each 10 kg decrease in body weight was correlated with 1.1% increase in fasting FMD [64], our results suggest that FMD can be increased by exercise training without weight loss. In regard to training frequency, almost all trials performed 3 days per week so that we cannot further analysis.

Although AE may be currently the most effective exercise modality for improving EF, focusing largely on AE cannot be a recommended treatment for most T2D patients who have the risk of CVD. Recent studies reported that low skeletal muscle mass is associated with increase in arterial stiffness [65, 66]. Ohara et al. [67] also reported that thigh muscle cross-sectional area in 1470 older adults significantly and independently correlated with arterial stiffness measured by brachial pulse wave velocity. In particular, T2D patients should take into account that glucose uptake and glycogen storage predominantly occurred in skeletal muscle [68]. Furthermore, considering two facts, (1) those aged 65 and older account for the largest proportion of total T2D patients [69]; (2) muscle weakness starts at age 50 [70] and more aggravates by age 65 [71], it is certainly necessary for T2D patients, especially elderly to improve vascular function and increase muscular strength and mass together in order to not only reduce the risk of CVD but also improve glycemic control, their fundamental problems. Therefore, we believe that combination of AE and RE should be considered as more optimized strategy for most T2D patients rather than unitary exercise modality. Further studies need to be warranted to devise new modality of combined exercise, such as circuit training being consist of AE and RE or low intensity-high repetition RE with short rest times or active recovery to enhance oxygen utilization and muscle protein synthesis at the same time.

There are some limitations in our study. First, in the EX, those who have other intervention, such as ET receptor blockade, meditation, and hypoxic environment were included. Although these supplementary interventions did not make significant effects on FMD, it could cause bias. Second, the methods measuring FMD are somewhat different between research groups, which might influence on the results. Third, only one study [42] was blinded for outcomes, diminishing the quality of studies. Fourth, there is the possibility of the Hawthorne effect influencing the results. However, there is not any control group in included studies which reported significant change in all outcomes although the control groups participated in a study but did not perform exercise training. Moreover, one of the inclusion criteria for eligible studies was training for at least 8 weeks, averagely 12 weeks which may be sufficient to induce certain physiological responses to exercise. Thus, we speculate that the Hawthorne effect might be trivial. Lastly, the number of studies included in our study may not be adequate, which could augment a risk of bias, however significant publication bias was not found in all variables.

We first investigated effects of exercise training on both vascular EF as well as shear rate AUC, baseline diameter, and BMI in T2D patients. The study design is valuable because on the basis of the finding, we can suggest low to moderate intensity training can be an alternative strategy for improving EF. Second, we performed meta-analysis based on studies targeting only T2D patients where EF is assessed by only brachial artery FMD, the major predictor for CVD and atherosclerosis, which importantly provides the validity of the results. Thus, we believe that this study extends our knowledge to provide an optimized therapeutic strategy to reduce the risk of CVD in T2D patients.

Conclusion

This systemic review and meta-analysis found that exercise training significantly increased brachial artery FMD in T2D patients without adverse events, but there was no change in shear rate AUC, baseline diameter, and BMI. Subgroups with low to moderate intensity increased FMD more than moderate to high intensity subgroups, suggesting that increase in NO production and bioavailability does not solely depend on an increase in shear stress, and the possibility of low to moderate training as a new alternative therapeutic strategy for T2D patients. There is an impressive small number of well conducted studies in this field. Further studies are needed to establish more optimized exercise prescription guideline for T2D patients.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

aerobic exercise

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CON:

-

control group

- CONT:

-

continuous training

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- EF:

-

endothelial function

- eNOS:

-

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ES:

-

effect size

- ET:

-

endothelin

- EX:

-

exercise group

- EXP:

-

experimental group

- FMD:

-

flow-mediated dilation

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HbA1c:

-

glycated hemoglobin

- HRmax:

-

maximum heart rate

- HRR:

-

hear rate reserve

- INT:

-

interval training

- METs:

-

metabolic equivalents

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- RE:

-

resistance exercise

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- T2D:

-

type 2 diabetes

- VO2peak :

-

peak oxygen consumption

- 1-RM:

-

one-repetition maximum

References

Fox CS, et al. Increasing cardiovascular disease burden due to diabetes mellitus: the framingham heart study. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1544–50.

American Heart Association. Statistics about American heart disease. 2015. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/Diabetes/WhyDiabetesMatters/Cardiovascular-Disease-Diabetes_UCM_313865_Article.jsp. Accessed Aug 2015.

Hadi HA, Suwaidi JA. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3(6):853–76.

Muniyappa R, Iantorno M, Quon MJ. An integrated view of insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):685–711.

Thijssen DH, et al. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300(1):H2–12.

Vita JA, Keaney JF. Endothelial function. Am Heart Assoc. 2002;106:640–2.

Corretti MC, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):257–65.

Vane JR, Änggård EE, Botting RM. Regulatory functions of the vascular endothelium. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(1):27–36.

Ando J, Yamamoto K. Effects of shear stress and stretch on endothelial function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(5):1389–403.

Larisa Way K, et al. The effect of exercise on vascular function and stiffness in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12(4):369–83.

Montero D, et al. Effects of exercise training on arterial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sports Med. 2013;43(11):1191–9.

Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115(10):1285–95.

Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Guyatt GH, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clin Res ed.). 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Andrews J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–25.

Inaba Y, Chen JA, Bergmann SR. Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by flow-mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26(6):631–40.

Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics. 1954;10(4):417–51.

Higgin J, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Hillsdale: NJ; 1988. p. 20–6.

Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochranehandbook.org.

Egger M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Green DJ, et al. Exercise-induced improvement in endothelial dysfunction is not mediated by changes in CV risk factors: pooled analysis of diverse patient populations. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(6):H2679–87.

Green DJ, et al. Comparison of resistance and conduit vessel nitric oxide-mediated vascular function in vivo: effects of exercise training. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97(2):749–55.

Madsen SM, et al. Functional and structural vascular adaptations following 8 weeks of low volume high intensity interval training in lower leg of type 2 diabetes patients and individuals at high risk of metabolic syndrome. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2015;121(5):178–86.

da Silva CA, et al. High-intensity aerobic training improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95(2):237–45.

Silva CAD, et al. Effect of high-intensity exercise on endothelial function in patients with T2DM. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 2016;22(2):126–30.

Allen JD, et al. Diabetes status differentiates endothelial function and plasma nitrite response to exercise stress in peripheral arterial disease following supervised training. J Diabetes Complicat. 2014;28(2):219–25.

Kluding PM, et al. Safety of aerobic exercise in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: single-group clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2015;95(2):223.

Billinger SA, et al. Aerobic exercise improves measures of vascular health in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(1):80–5.

Maiorana A, et al. The effect of combined aerobic and resistance exercise training on vascular function in type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(3):860–6.

Choi KM, et al. Effects of exercise on sRAGE levels and cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):3751–8.

Wycherley TP, et al. Effect of caloric restriction with and without exercise training on oxidative stress and endothelial function in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10(11):1062–73.

Wycherley TP, et al. Long-term effects of weight loss with a very-low carbohydrate, low saturated fat diet on flow mediated dilatation in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Atherosclerosis. 2016;252:28–31.

Schreuder TH, et al. Life-long physical activity restores metabolic and cardiovascular function in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(3):619–27.

Xinghai L. Effect of Qigong Baduanjin on endothelium-dependent arterial dilation of type 2 diabetes. J Shenyang Sport Univ. 2009;1:013.

Rittig K, et al. Reducing visceral adipose tissue mass is essential for improving endothelial function in type 2 diabetes prone individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(2):575–9.

Han KA, et al. Effects of moderate versus vigorous intensity exercise training on inflammatory markers, endothelial function, and insulin resistance in the patients with type 2 diabetes: longitudinal study in diabetes. Alexandria: Amer Diabetes Assoc; 2009.

Dhungana R, et al. Exercise effects on a novel marker of local shear stress and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(13):E1746.

Suntraluck S, Tanaka H, Suksom D. The relative efficacy of land-based and water-based exercise training on macro-and micro-vascular functions in older patients with type 2 diabetes. J Aging Phys Act. 2017;25(3):446–52.

Francois ME, Durrer C, Little J. High-intensity interval training with or without post-exercise milk consumption improves cardiovascular function in patients with type 2 diabetes. FASEB J. 2017;31(1 Supplement):1035.2.

Schreuder TH, et al. Impact of hypoxic versus normoxic training on physical fitness and vasculature in diabetes. High Alt Med Biol. 2014;15(3):349–55.

Schreuder TH, et al. Randomized controlled trial using bosentan to enhance the impact of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Physiol. 2014;99(11):1538–47.

Gainey A, et al. Effects of Buddhist walking meditation on glycemic control and vascular function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:92–7.

Kwon HR. Effects of aerobic exercise vs resistance training on endothelial function in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35(4):364–73.

Okada S, et al. Effect of exercise intervention on endothelial function and incidence of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(8):828–33.

Schreuder TH, et al. Time-course of vascular adaptations during 8 weeks of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and middle-aged controls. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(1):187–96.

Barone Gibbs B, et al. A randomized trial of exercise for blood pressure reduction in type 2 diabetes: effect on flow-mediated dilation and circulating biomarkers of endothelial function. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224(2):446–53.

Mitranun W, et al. Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro- and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):e69–76.

Ignarro L. Nitric oxide as a unique signaling molecule in the vascular system: a historical overview. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;53(4):503–14.

Tousoulis D, et al. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10(1):4–18.

Di Francescomarino S, et al. The effect of physical exercise on endothelial function. Sports Med. 2009;39(10):797.

Higashi Y, Yoshizumi M. Exercise and endothelial function: role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and oxidative stress in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;102(1):87–96.

Hwang M-H, Kim S. Type 2 diabetes: endothelial dysfunction and exercise. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2014;18(3):239.

Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Sci. 2005;109(2):143–59.

Thijssen DH, et al. Impact of inactivity and exercise on the vasculature in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):845–75.

Green DJ, et al. Effect of exercise training on endothelium-derived nitric oxide function in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561(1):1–25.

Tinken TM, et al. Shear stress mediates endothelial adaptations to exercise training in humans. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):312–8.

Thijssen D, et al. Exercise training modulates the pattern of diameter change of the flow-mediated dilation in healthy young men. Acta Physiol. 2011;201:427–34.

Newcomer SC, Thijssen DH, Green DJ. Effects of exercise on endothelium and endothelium/smooth muscle cross talk: role of exercise-induced hemodynamics. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(1):311–20.

Pyke KE, Tschakovsky ME. The relationship between shear stress and flow-mediated dilatation: implications for the assessment of endothelial function. J Physiol. 2005;568(2):357–69.

Alzheimer’s A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2013;9(2):1–71.

Yoshizawa M, et al. Effect of 12 weeks of moderate—intensity resistance training on arterial stiffness: a randomised controlled trial in women aged 32–59 years. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(8):615–8.

Miyachi M. Effects of resistance training on arterial stiffness: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(6):393–6.

Joris PJ, Zeegers MP, Mensink RP. Weight loss improves fasting flow-mediated vasodilation in adults: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239(1):21–30.

Sampaio RAC, et al. Arterial stiffness is associated with low skeletal muscle mass in Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(S1):109–14.

Kim TN, et al. Skeletal muscle mass to visceral fat area ratio is associated with metabolic syndrome and arterial stiffness: the Korean sarcopenic obesity study (KSOS). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(2):285–91.

Ohara M, et al. Sarcopenic obesity and arterial stiffness, pressure wave reflection and central pulse pressure: the J-SHIPP study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(1):214–7.

Miller W, Sherman W, Ivy J. Effect of strength training on glucose tolerance and post-glucose insulin response. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16(6):539–43.

American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes. 2017. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed 5 Apr 2017.

Lindle RS, et al. Age and gender comparisons of muscle strength in 654 women and men aged 20–93 year. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83(5):1581–7.

Baumgartner RN, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(8):755–63.

Authors’ contributions

JH, MH, MT and YJ drafted the manuscript. JH, MH and YJ participated in study design. JH and MH participated in statistical analysis and interpretation of results. JH and RD participated in literature review and data extraction. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank authors in cited studies who provided additional information.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no received funding for this study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, JH., Lee, R., Hwang, MH. et al. The effects of exercise on vascular endothelial function in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr 10, 15 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0316-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0316-7