Abstract

Background

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are used to evaluate social and psychological interventions and inform policy decisions about them. Accurate, complete, and transparent reports of social and psychological intervention RCTs are essential for understanding their design, conduct, results, and the implications of the findings. However, the reporting of RCTs of social and psychological interventions remains suboptimal. The CONSORT Statement has improved the reporting of RCTs in biomedicine. A similar high-quality guideline is needed for the behavioural and social sciences. Our objective was to develop an official extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 Statement (CONSORT 2010) for reporting RCTs of social and psychological interventions: CONSORT-SPI 2018.

Methods

We followed best practices in developing the reporting guideline extension. First, we conducted a systematic review of existing reporting guidelines. We then conducted an online Delphi process including 384 international participants. In March 2014, we held a 3-day consensus meeting of 31 experts to determine the content of a checklist specifically targeting social and psychological intervention RCTs. Experts discussed previous research and methodological issues of particular relevance to social and psychological intervention RCTs. They then voted on proposed modifications or extensions of items from CONSORT 2010.

Results

The CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist extends 9 of the 25 items from CONSORT 2010: background and objectives, trial design, participants, interventions, statistical methods, participant flow, baseline data, outcomes and estimation, and funding. In addition, participants added a new item related to stakeholder involvement, and they modified aspects of the flow diagram related to participant recruitment and retention.

Conclusions

Authors should use CONSORT-SPI 2018 to improve reporting of their social and psychological intervention RCTs. Journals should revise editorial policies and procedures to require use of reporting guidelines by authors and peer reviewers to produce manuscripts that allow readers to appraise study quality, evaluate the applicability of findings to their contexts, and replicate effective interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

When feasible and appropriate, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are used to evaluate social and psychological interventions, and to inform policy and practice decisions [1,2,3,4,5]. To use reports of RCTs, readers need information about their design, context, conduct, analysis, results, and interpretation. Like other types of research, RCTs can provide biased estimates of intervention effects if they are not conducted well, and syntheses of these RCTs may be biased if the trials are not reported completely [6, 7]. Consequently, accurate, complete, and transparent reports of RCTs are essential for maximising their value [8], allowing replication studies to build the evidence base [9], and facilitating the comparison and implementation of effective interventions in real-world contexts [10].

Recent reviews have shown that reports of RCTs of social and psychological interventions are often insufficiently accurate, comprehensive, and transparent to replicate trials, assess their quality, and understand for whom and under what circumstances an intervention should be delivered [11,12,13]. For instance, authors often do not report data on intervention implementation [14], such as the specific techniques employed by intervention providers; adaptation or tailoring of the intervention to specific groups or individuals; materials used to support intervention implementation; and participant behaviours [15]. Inadequate reporting can make it difficult for researchers to replicate trials, for intervention developers to design effective interventions, and for providers to use the interventions in practice [16]. A lack of sharing trial protocols, outcome data, and materials required to implement social and psychological interventions has been identified as a major reason for limitations in the ability of behavioural and social scientists to reproduce trial procedures, replicate trial results, and effectively synthesise evidence on these interventions [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The review of trials that we conducted in the first phase of this project (n = 239) revealed that many CONSORT items were poorly reported in the behavioural and social science literature. Such items included identification as a randomised trial in titles; information about masking, methods for sequence generation, and allocation concealment; and details about the actual delivery of the interventions. Only 11 of 40 journals we examined referenced reporting guidelines in ‘Instructions to Authors’ [11]. This inefficient use of resources for research likely contributes to the suboptimal dissemination of potentially effective interventions [8, 22], overestimations of intervention efficacy [23], and research waste of investment to the order of hundreds of billions of dollars [22]. As in other areas of research, transparent and detailed reporting of social and psychological intervention RCTs is needed to minimise reporting biases and maximise the credibility and utility of this research evidence [24, 25].

The CONSORT Statement

To address the problems in scientific manuscripts outlined above, reporting guidelines have been developed that include minimum standards for describing specific types of research [26]. Reporting guidelines do not provide recommendations for study design or conduct. Instead, they focus on reporting what was done (methods) and what was found (results). In 1996, a group of scientists and journal editors published the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statement to help authors report RCTs in biomedicine completely and transparently [27]. In light of feedback and emerging evidence, the CONSORT Group updated this reporting guideline in 2001 [28] and again in 2010 [29]. CONSORT 2010 includes a 25-item checklist and flow diagram. An extensive Explanation and Elaboration (E&E) document serves as a user manual that explains the rationale behind each checklist item, provides the methodological rationale for each checklist item, and gives examples of trial details adequately reported in accordance with each checklist item [26].

The CONSORT Statement has had an important impact in medicine. An early evaluation showed that reporting in the BMJ, Lancet, and JAMA improved after the publication of the first CONSORT Statement [30]. Systematic reviews comparing articles in medical journals endorsing CONSORT compared with journals not endorsing it found that the former are significantly more likely to describe the method of sequence generation, allocation concealment, and participant flow [31]. These effects remain even after controlling for the impact factor of the journals and study outcomes [32]. Over 600 journals and prominent editorial groups (including the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, the Council of Science Editors, and the World Association of Medical Editors) officially endorse the CONSORT Statement.

Scope of CONSORT-SPI 2018

The CONSORT 2010 Statement focuses on individually randomised two-group parallel trials [29]. To address the varying amount of additional information needed for different types of trial, the CONSORT Group has created extensions (http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions). These extensions target different types of trial designs, such as cluster randomised [33], noninferiority [34], pragmatic [35], N-of-1 [36], and feasibility [37]; different types of trial data, such as patient-reported outcomes [38], abstracts [39], and harms [40]; and different types of intervention (see next section) [41,42,43]. Intervention extensions of CONSORT are organised by techniques, such as non-pharmacologic [41], herbal medicinal products [42], and acupuncture [43].

Social and psychological interventions go beyond simply adding techniques or using different techniques compared to biomedical interventions; they often use concepts, theories, and taxonomies that are distinct from those used by the biomedical scientists targeted by the CONSORT extension for non-pharmacologic treatments [21, 44,45,46,47,48]. To delineate the scope of CONSORT for social and psychological interventions (CONSORT-SPI), we define interventions by their mechanisms of action: i.e., how these interventions function to affect desired outcomes [49, 50]. That is, social and psychological interventions are actions intended to modify processes and systems that are social and psychological in nature (such as cognitions, emotions, behaviours, norms, relationships, and salient aspects of the environment) and are hypothesised to be influences on outcomes of interest [51, 52].

Social and psychological interventions can be complex in several ways [12, 50]. For example, these interventions cover an assortment of coordinated actions—such as practices, programmes, and policies—that often involve multiple interacting components. The units targeted by these interventions may include individuals, groups, or even places, and outcomes may be measured at any of these levels. The behaviours of both providers and recipients must be understood if the intervention and its effects are to be understood [53,54,55]. Social and psychological interventions may not follow strictly standardised implementation procedures [56], and effects may depend on aspects of the hard-to-control dynamic systems in which they occur [57,58,59]. For these reasons, readers of social and psychological intervention research are interested in more than just effect estimates—they require information about how and why these interventions work, for whom, and under what conditions [60].

Methods

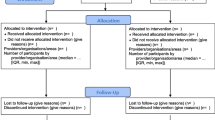

We developed an official CONSORT Extension that addresses the minimum criteria that need to be met when reporting RCTs evaluating the effects of social and psychological interventions (CONSORT-SPI 2018). We followed recommended practices for developing and disseminating reporting guidelines [26] as described in the study protocol [61]. The methods and results of the systematic review, Delphi process, and consensus meeting followed a pre-specified protocol reported in full elsewhere [11, 61]. We briefly summarise the process below (Fig. 1).

Systematic reviews

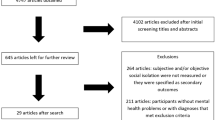

We first conducted a systematic review to assess the adherence of RCTs evaluating social and psychological interventions to existing reporting standards, and to identify potential items for the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and flow diagram [11].

Online Delphi process

We then conducted an international online Delphi process between September 2013 and February 2014 to prioritise the list of potential items for the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and flow diagram that were identified in the systematic review. To encourage widespread participation, we published commentaries in several journals publishing trial reports in the fields of addiction, criminology, education, adult and child psychology and psychiatry, public health, and social work [11, 62,63,64,65,66,67,68], directing readers to a recruitment website where they could register. We also invited members of professional bodies, funders, policymakers, journal editors, practitioners, user representatives, and other stakeholders to participate. We encouraged all identified stakeholders to invite any further colleagues to participate. We sent these participants a two-round survey to rate the importance of including proposed items in the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and to provide qualitative feedback (survey items can be accessed at the project’s ReShare site: https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-851981). We synthesised the results of the first survey and sent these to participants, who then completed the second survey, which was designed to explore areas of disagreement and to resolve questions arising during the first round.

Consensus meeting

Following the Delphi process, we held a three-day in-person consensus meeting to determine the content of the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and flow diagram, as well as the accompanying E&E document (March 2014). We used established methods [69] from previous CONSORT meetings [29, 35, 41, 70]. Participants included 31 experts from the Delphi process (see Table 6 in the Appendix), whom we selected purposively to include key stakeholders from targeted disciplines (e.g. public health, social work, education, criminology, and clinical psychology) and professional roles (e.g. trialists, funders, and journal editors) [71].

Prior to the meeting, we sent participants background literature [9, 11, 26, 39, 61, 64, 72], results from the Delphi process, and the meeting agenda. On the first day, participants discussed the background literature and its applicability to the various disciplines and professional roles represented at the meeting. During the second day, participants discussed and voted on potential checklist and flow diagram items nominated during the Delphi process using anonymous electronic ballots. On the third day, participants voted on the remaining items and discussed strategies for dissemination. Participants were asked to consider the value of each item based on the evidence presented and to vote on whether each item was essential when reporting all social and psychological intervention RCTs. When voting, participants could select ‘exclude’, ‘include’, or ‘unsure’.

In the first round of voting, only items endorsed as ‘include’ by ≥70% of participants were included in the checklist [73, 74]. We excluded all other items unless at least two participants proposed they be reconsidered. In this second round of voting, items endorsed as ‘include’ by ≥80% of participants were also incorporated in the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist. Participants suggested that several ‘excluded’ items should be discussed in the E&E document.

Post-meeting activities

After the consensus meeting, we finalised the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and flow diagram. We then drafted the Extension Statement (this manuscript), as well as an E&E document that serves as a user manual for the checklist. We distributed these documents to consensus meeting participants for feedback and revision, and we incorporated their comments in the final version of this manuscript and the accompanying E&E. We also discussed how best to optimise our strategy for disseminating and implementing these documents.

Results

Systematic review

The systematic review of reporting guidance identified 14 relevant reporting guidelines and 5 reporting assessment tools. These tools included a total of 147 potential items to consider for the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist, 89 of which were not included in the CONSORT checklist [11].

Online Delphi process

With input from the project’s International Advisory Group, we included 77 potential checklist items from the systematic review in the first round of the modified Delphi process. We recruited 384 Delphi participants from 32 countries working in over a dozen areas of social and psychological intervention, including academics, researchers, practitioners, journal editors, research funders, policymakers, and recipients of social and psychological interventions. The Delphi process yielded 58 potential items as important to consider for inclusion in the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist.

Consensus meeting

During the consensus meeting, participants voted to extend 9 of the 25 items in the CONSORT 2010 checklist: background and objectives, trial design, participants, interventions, statistical methods, participant flow, baseline data, outcomes and estimation, and funding. These extended checklist items addressed the need for reports of RCTs of social and psychological interventions to describe: the hypotheses for how the intervention might work, the eligibility criteria for settings and providers, the actual provider delivery and participant uptake of the interventions, the intervention materials, how missing data were handled, participant recruitment, socioeconomic baseline variables, availability of trial data, author declarations of interest, involvement of the intervention developer in the trial, and details of any incentives offered (Table 1). Participants also voted to add a new item about stakeholder involvement, and they recommended modifications to existing CONSORT 2010 checklist items (Table 2). The flow diagram (Fig. 2) to address the unique needs of social and psychological intervention trials was also modified—specifically, the number of participants approached during enrolment and the number of providers, organisations, and areas (as appropriate) allocated to each trial arm. To further facilitate use of CONSORT-SPI 2018, we have provided a tailored CONSORT Extension for Abstracts (Table 3) [39] and a CONSORT Extension for Cluster Randomised Trials (Tables 4 and 5) [33] for social and psychological intervention trials.

Discussion

The CONSORT-SPI 2018 Extension is designed to assist authors in writing reports of social and psychological intervention RCTs and to assist peer reviewers and editors in assessing these manuscripts. While we recommend that authors report items in the checklist in the relevant manuscript section (i.e., introduction, methods, results, or discussion), the format of an article will depend on journal style, editorial decisions, expectations within a particular research area, and author discretion. At a minimum, authors should address each checklist item somewhere in the article with the appropriate level of detail and clarity. We recommend subheadings within major sections—particularly the methods and results sections—to help ease of reading. The accompanying CONSORT-SPI 2018 E&E document is a user manual for the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist, providing a concise rationale for and description of how best to adhere to each checklist item. We recommend that authors preparing reports of social and psychological intervention RCTs consult the CONSORT-SPI 2018 E&E document when using the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist.

This guideline may prove useful to several different stakeholders [75]. Researchers can use CONSORT-SPI 2018, along with the SPIRIT Statement, during trial design to ensure they consider the essential study aspects they will have to describe in future manuscripts. Use of CONSORT-SPI 2018 throughout a trial (from design to reporting) can help improve the accuracy, completeness, and transparency of the final manuscript. Journal editors can enforce policies and procedures to ensure that CONSORT-SPI 2018 is actually used by authors, editors and peer reviewers to improve the social and psychological RCT manuscripts they publish [76]. Research funders who adopt CONSORT-SPI 2018 and other reporting guidelines may receive higher quality grant applications, as well as facilitate the commissioning of the most important and rigorous studies while helping to reduce research waste. Policymakers, practitioners, and systematic reviewers who encourage researchers to use CONSORT-SPI 2018 may find this leads to higher quality publications, which these stakeholders can then use to identify and implement effective interventions for populations and settings of interest. In addition, faculty could use reporting guidelines to train the next generation of researchers, peer reviewers, and journal editors [77].

In highlighting prospective trial registration [78], the publication of protocols [79], and increased sharing of trial data [16, 80], all of which are uncommon in social and psychological intervention research, CONSORT-SPI 2018 also complements other efforts to improve research transparency. Examples of such efforts include the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (which will replace CONSORT 2010 Item 5) [9], the Behaviour Change Technique taxonomy [21, 44], the Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences [81], the Data Access and Research Transparency Statement [82], the Center for Open Science [19], the Transparency and Openness Promotion guidelines [16], and the Human Behaviour-Change Project [83].

Strengths and limitations

We followed recommended best practices in the development of these reporting guidelines and advocate their use to future reporting guideline developers [26]. A challenge that we experienced, and which other reporting guideline developers have faced [84], was the large number of potential checklist items that participants considered to be important for a CONSORT-SPI 2018 guideline. As with the CONSORT 2010 Statement, CONSORT-SPI 2018 represents a set of minimum reporting criteria and does not preclude individual authors from addressing other issues that they deem important to ensure complete and transparent reporting. For example, for social and psychological interventions utilising mobile phones, additional details may need to be reported in trial manuscripts [85].

In addition, as in the development of previous CONSORT guidelines, other items fundamental to an RCT have not been included (such as approval by an institutional ethical review board) because journals and institutions address these issues in other ways [29]. We encourage users of this guideline to provide feedback on the appropriateness of the content in the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and its accompanying E&E document.

Endorsement

As a recognised extension of the CONSORT 2010 Statement, journals and organisations already endorsing the CONSORT guidelines can easily extend their support to CONSORT-SPI 2018. We encourage other journals and organisations that publish social and psychological intervention RCTs to endorse CONSORT-SPI 2018 and to register their official support on the CONSORT website (http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/endorsement). Journal endorsement policies that include monitoring of adherence to the checklist are essential for complete and transparent reporting [31]. To maximise the potential impact of CONSORT-SPI 2018, editors should consider requiring authors to submit a completed CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist as a separate document when reporting social and psychological intervention RCTs, and we recommend that editors should check that all items have been included before sending manuscripts for peer review. Endorsing journals should consider adding the following statement to their ‘Instructions to Authors’ [36]:

JOURNAL NAME requires a completed CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist as a condition for submitting manuscripts about randomised trials of social and psychological interventions. We recommend that your submission addresses each item in the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist. Taking the time to ensure your manuscript meets these basic reporting requirements will greatly improve your manuscript, and may potentially enhance its chances for eventual publication.

We also recommend that researchers, editors, peer reviewers, funders, and educators consult the CONSORT website (http://www.consort-statement.org) for other relevant CONSORT Extensions (e.g. the extension for cluster randomised trials) [33], as well as the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) Network for up-to-date information on other reporting guidelines (http://www.equator-network.org) that may be of relevance to their study.

Conclusion

CONSORT-SPI 2018, like other CONSORT guidelines, is an evolving tool that requires regular reappraisal and modifications as new evidence emerges and as scientific consensus changes. We invite interested stakeholders to contact us with feedback or to contribute to the guideline’s ongoing development, including individuals or groups who wish to translate the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist into other languages or those who wish to evaluate the impact of the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist on future trial reporting [31, 86]. To provide feedback and access the most recent version of the CONSORT-SPI 2018 checklist and E&E document, visit the project (https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/social-policy/departments/social-policy-sociology-criminology/research/projects/2017/Consort-SPI.aspx) and CONSORT websites (http://www.consort-statement.org).

References

Petrosino A, Boruch RF, Rounding C, McDonald S, Chalmers I. The Campbell collaboration Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Trials Register (C2-SPECTR) to facilitate the preparation and maintenance of systematic reviews of social and educational interventions. Eval Res Educ. 2000;14(3–4):206–19.

Bristow D, Carter L, Martin S. Using evidence to improve policy and practice: the UK what works Centres. Contemp Soc Sci. 2015;10(2):126–37.

Social and Behavioral Sciences Team. 2015 Annual Report. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, National Science and Technology Council; 2015.

Clark ML, Thapa S. Systematic reviews in the bulletin. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:3.

Petrosino A. Reflections on the genesis of the Campbell collaboration. Exp Criminol. 2013;8(2):9–12.

Oliver S, Bagnall AM, Thomas J, et al. Randomised controlled trials for policy interventions: a review of reviews and meta-regression. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(16):1–165.

Goodman S, Dickersin K. Metabias: a challenge for comparative effectiveness research. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):61–2.

Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: Who's listening? Lancet. 2015; Available online 27 September 2015:doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(1015)00307-00304

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou P, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Sheikh A, et al. Developing standards for reporting implementation studies of complex interventions (StaRI): a systematic review and e-Delphi. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):42.

Grant S, Mayo-Wilson E, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Montgomery P. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. J Exp Criminol. 2013;9(3):355–67.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw J, Eccles M. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci. 2009;4:40.

Mayo-Wilson E. Reporting implementation in randomized trials: proposed additions to the consolidated standards of reporting trials statement. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):630–3.

Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, Shepperd S. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1472–4.

Nosek BA, Alter G, Banks GC, et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science. 2015;348:1422–5.

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349(6251):aac4716.

McNutt M. Reproducibility. Science. 2014;343(6168):229.

Open Science Collaboration. An open, large-scale, collaborative effort to estimate the reproducibility of psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(6):657–60.

Tajika A, Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Furukawa TA. Replication and contradiction of highly cited research papers in psychiatry: 10-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2015; Available online July 2015:doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.1113.143701

Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis JJ, Hardeman W. Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(99):1–187.

Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):267–76.

Driessen E, Hollon SD, Bockting CLH, Cuijpers P, Turner EH. Does publication bias inflate the apparent efficacy of psychological treatment for major depressive disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis of us national institutes of health-funded trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137864.

Ioannidis JP, Munafo MR, Fusar-Poli P, Nosek BA, David SP. Publication and other reporting biases in cognitive sciences: detection, prevalence, and prevention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(5):235–41.

Cybulski L, Mayo-Wilson E, Grant S. Improving transparency and reproducibility: registering clinical trials of psychological interventions prospectively and completely. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(9):753–67.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217.

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–9.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D, for the CONSORT Group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1191–4.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:698–702.

Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, for the CONSORT Group. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: A comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285:1992–5.

Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:MR000030.

Devereaux PJ, Manns BJ, Ghali WA, Quan H, Guyatt GH. The reporting of methodological factors in randomized controlled trials and the association with a journal policy to promote adherence to the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) checklist. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23:380–8.

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661.

Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2594–604.

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390.

Vohra S, Shamseer L, Sampson M, et al. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015 statement. BMJ. 2015;350:h1738.

Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239.

Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814–22.

Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, et al. CONSORT for reporting randomised trials in journal and conference abstracts. Lancet. 2008;371:281–3.

Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781–8.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz K, Ravaud P, for the CONSORT group. Methods and processes of the CONSORT group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):W60–6.

Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, Moher D, Barnes J, Bombardier C. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:364–7.

MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. Revised STandards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000261.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A guide to designing interventions. UK: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Michie S, West R, Campbell R, Brown J, Gainforth H. ABC of Behaviour Change Theories: An essential resource for researchers, policy makers and practitioners. UK: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Davis RE, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):323–44.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309.

Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ, Richman JM, Day SH. Intervention research: developing social programs. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. London: Medical Research Council; 2008. www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance

Grant S. Development of a CONSORT Extension for Social and Psychological Interventions. Oxford: Social Policy & Intervention, University of Oxford; 2014.

Institute of Medicine. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: A framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC: the National Academies Press; 2015.

Bonell C, Jamal F, Melendez-Torres GJ, Cummins S. ‘Dark logic’: theorising the harmful consequences of public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(1):95–8.

May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:18.

Øvretveit J. Evaluating improvement and implementation for health. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2014.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how ‘out of control’ can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–3.

Bonell C. The utility of randomized controlled trials of social interventions: an examination of two trials of HIV prevention. Critical Public Health. 2002;12(4):321–34.

Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Belmont: Wadsworth; 2002.

Sniehotta FF, Araújo-Soares V, Brown J, Kelly MP, Michie S, West R. Complex systems and individual-level approaches to population health: a false dichotomy? Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(9):e396–7.

Weiss MJ, Bloom HS, Brock T. A conceptual framework for studying the sources of variation in program effects. New York: MDRC; 2013.

Montgomery P, Grant S, Hopewell S, et al. Protocol for CONSORT-SPI: an extension for social and psychological interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:99.

Grant S, Montgomery P, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Mayo- Wilson E. Letter to the editor: new guidelines are needed to improve the reporting of trials in addiction sciences. Addiction. 2013;108:1687–8.

Grant S, Montgomery P, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. Res Soc Work Pract. 2013;23(6):595–602.

Mayo-Wilson E, Grant S, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Montgomery P. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. Trials. 2013;14:242.

Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Grant S. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:250–4.

Montgomery P, Grant S, Hopewell S, Macdonald G, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. Br J Soc Work. 2013;43(5):1024–38.

Montgomery P, Mayo-Wilson E, Hopewell S, G M, Moher D, Grant S. Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1741–6.

Gardner F, Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P, et al. Editorial perspective: the need for new guidelines to improve the reporting of trials in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):810–2.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(376):376–80.

Hopewell S, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high impact factor medical journals: a survey of journal editors and journal ‘instructions to authors. Trials. 2008;9:20.

Moher D, Weeks L, Ocampo M, et al. Describing reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):718–42.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schultz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):i-iv, 1–88.

Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000393.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, Boutron I. Effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e4178.

Moher D, Altman DG. Four proposals to help improve the medical research literature. PLoS Med. 2015;12(9):e1001864.

Harrison BA, Mayo-Wilson E. Trial registration: understanding and preventing reporting bias in social work research. Res Soc Work Pract. 2014;24(3):372–6.

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586.

Mayo-Wilson E, Doshi P, Dickersin K. Are manufacturers sharing data as promised? BMJ. 2015;351:h4169.

Miguel E, Camerer C, Casey K, et al. Promoting transparency in social science research. Science. 2014;343(6166):30–1.

Data Access and Research Transparency (DA-RT): a joint statement by political science journal editors. Pol Sci Res Methods. 2015;3:421. https://www.dartstatement.org/.

Michie S, Thomas J, Johnston M, et al. The human behaviour-change project: harnessing the power of artificial intelligence and machine learning for evidence synthesis and interpretation. Implement Sci. 2017;12:121.

Tetzlaff JM, Moher D, Chan AW. Developing a guideline for clinical trial protocol content: Delphi consensus survey. Trials. 2012;13(1):176.

Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, et al. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ. 2016;352:i1174.

Stevens A, Shamseer L, Weinstein E, et al. Relation of completeness of reporting of health research to journals’ endorsement of reporting guidelines: systematic review. BMJ. 2014;348:g3804.

Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the stakeholders who have provided their input to the project.

CONSORT-SPI Group: J. Lawrence Aber (Willner Family Professor of Psychology and Public Policy and University Professor, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University), Doug Altman (Professor of Statistics in Medicine and Director of the UK EQUATOR Centre, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford), Kamaldeep Bhui (Professor of Cultural Psychiatry & Epidemiology, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University of London), Andrew Booth (Reader in Evidence Based Information Practice and Director of Information, Information Resources, University of Sheffield), David Clark (Professor and Chair of Experimental Psychology, Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford), Peter Craig (Senior Research Fellow, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow), Manuel Eisner (Wolfson Professor of Criminology, Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge), Mark W. Fraser (John A. Tate Distinguished Professor for Children in Need, School of Social Work, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Frances Gardner (Professor of Child and Family Psychology, Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford), Sean Grant (Behavioural & Social Scientist, Behavioural & Policy Sciences, RAND Corporation), Larry Hedges (Board of Trustees Professor of Statistics and Education and Social Policy, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University), Steve Hollon (Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of Psychology, Psychological Sciences, Vanderbilt University), Sally Hopewell (Associate Professor, Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit, University of Oxford), Robert Kaplan (Professor Emeritus, Department of Health Policy and Management, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles), Peter Kaufmann (Leader, Behavioural Medicine and Prevention Research Group, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health), Spyros Konstantopoulos (Professor, Department of Counselling, Educational Psychology, and Special Education, Michigan State University), Geraldine Macdonald (Professor of Social Work, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol), Evan Mayo-Wilson (Assistant Scientist, Division of Clinical Trials and Evidence Synthesis, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University), Kenneth McLeroy (Regents & Distinguished Professor, Health Promotion and Community Health Sciences, Texas A&M University), Susan Michie (Professor of Health Psychology and Director of the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London), Brian Mittman (Research Scientist, Department of Research and Evaluation, Division of Health Services Research and Implementation Science, Kaiser Permanente), David Moher (Senior Scientist, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Paul Montgomery (Professor of Social Intervention, Department of Social Work and Social Care, University of Birmingham), Arthur Nezu (Distinguished University Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, Drexel University), Lawrence Sherman (Director of the Jerry Lee Centre for Experimental Criminology and Chair of the Cambridge Police Executive Programme, the Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge.), Edmund Sonuga-Barke (Professor of Developmental Psychology, Psychiatry, and Neuroscience, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London), James Thomas (Professor Social Research and Policy, UCL Institute of Education, University College London), Gary VandenBos (Executive Director, Office of Publications and Databases, American Psychological Association), Elizabeth Waters (Jack Brockhoff Chair of Child Public Health, McCaughey VicHealth Centre for Community Wellbeing, Melbourne School of Population & Global Health, University of Melbourne), Robert West (Professor of Health Psychology and Director of Tobacco Studies, Health Behaviour Research Centre, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health) and Joanne Yaffe (Professor, College of Social Work, University of Utah).

Funding

This project is funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ES/K00087X/1).

Availability of data and materials

Methodological protocols, data collection materials, and data from the Delphi process and consensus meeting can be requested from ReShare, the UK Data Service’s online data repository (doi: https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-851981).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

PM, SG and EMW conceived of the idea for the project. PM, SG, EMW, GM, SM, SH and DM led the project and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Department Research Ethics Committee for the Department of Social and Intervention, University of Oxford (reference 2011-12_83).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SG’s spouse is a salaried-employee of Eli Lilly and Company, and owns stock. SG has accompanied his spouse on company-sponsored travel. SH and DM are members of the CONSORT Group. All other authors declare no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 6 lists the members of the CONSORT-SPI Group who were participated to represent the stakeholder groups in the consensus meeting.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Montgomery, P., Grant, S., Mayo-Wilson, E. et al. Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: the CONSORT-SPI 2018 Extension. Trials 19, 407 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2733-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2733-1