Abstract

Background

Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH2) regulates the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) through the metabolism of the endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). Pilot studies have associated the rs805305 SNP of DDAH2 with ADMA concentrations in sepsis. This study explored the impact of the rs805305 polymorphism on DDAH activity and outcome in septic shock.

Methods

We undertook a secondary analysis of data and samples collected during the Vasopressin versus noradrenaline as initial therapy in septic shock (VANISH) trial. Plasma and DNA samples isolated from 286 patients recruited into the VANISH trial were analysed. Concentrations of L-Arginine and the methylarginines ADMA and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) were determined from plasma samples. Whole blood and buffy-coat samples were genotyped for polymorphisms of DDAH2. Clinical data collected during the study were used to explore the relationship between circulating methylarginines, genotype and outcome.

Results

Peak ADMA concentration over the study period was associated with a hazard ratio for death at 28 days of 3.3 (95% CI 2.0–5.4), p < 0.001. Reduced DDAH activity measured by an elevated ADMA:SDMA ratio was associated with a reduced risk of death in septic shock (p = 0.03). The rs805305 polymorphism of DDAH2 was associated with reduced DDAH activity (p = 0.004) and 28-day mortality (p = 0.02). Mean SOFA score and shock duration were also reduced in the less common G:G genotype compared to heterozygotes and C:C genotype patients (p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively).

Conclusions

Plasma ADMA is a biomarker of outcome in septic shock, and reduced DDAH activity is associated with a protective effect. The polymorphism rs805305 SNP is associated with reduced mortality, which is potentially mediated by reduced DDAH2 activity.

Trial registration

ISRCTN Registry, ISRCTN20769191. Registered on 20 September 2012.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sepsis arises when an infective organism provokes a series of host responses, the dysregulation of which leads to organ dysfunction. There is a spectrum of disease which, at its most severe, is characterised by cellular, tissue, vascular and cardiac abnormalities [1, 2]. Collectively these pathological changes lead to altered cellular metabolic function, impaired tissue oxygen availability and reduced utilisation by the tissues [3,4,5,6]. Sepsis is a major health challenge in both the developing and the developed world, with more than 2 million cases in the USA [7] and an estimated 5.3 million deaths worldwide [8] each year.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a critical mediator of the vascular, immune and cardiac response to infection [3, 9,10,11,12]. NO is synthesised by the three isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in a process that is tightly regulated at every stage from gene expression to substrate and co-factor availability [13]. The discovery of a family of arginine derivatives, known as the methylarginines (MA), which act as inhibitors by competing with the binding of L-arginine to the active site of the NOS enzyme, is one of few examples where an enzyme system is regulated by endogenous competitive inhibition [14].

Three MA subtypes have been identified in mammals, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) and monomethylarginine (L-NMMA) [15]. Within the cell, both ADMA and L-NMMA act through competitive inhibition of L-arginine binding to the NOS enzymes (Fig. 1). L-NMMA and ADMA are equipotent but L-NMMA is present at only around 10% of the concentration of ADMA in most tissues and so plays a lesser role in the regulation of NOS activity [16]. By contrast, SDMA does not compete with L-arginine at physiological and pathophysiological concentrations and has no apparent impact on NOS activity. Elevation of plasma ADMA concentration has been associated with risk in cardiac [17] and chronic renal disease [18]. In sepsis, a number of studies in heterogeneous clinical populations have suggested that plasma ADMA concentration is associated with illness severity and death [19,20,21,22,23].

Representative image of the synthesis and regulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) in sepsis. Protein arginine methyl transferases (PRMT) catalyse the methylation of arginine containing protein residues to ADMA and SDMA, which are released upon proteolysis. ADMA and SDMA are transported via the y+ cationic amino acid transporter into and out of the circulation. SDMA is not metabolised in most cell,s whereas ADMA is metabolised by the two isoforms of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in a wide range of tissues. ADMA acts intracellularly to inhibit nitric oxide synthase (NOS), SDMA has no action on NOS isoforms. SDMA is cleared by the kidney largely unchanged and in small part through metabolism by AGXT2 (not shown). ADMA is largely metabolised by DDAH to dimethylamine (DMA); a small amount is cleared unchanged through the kidney. In sepsis, the synthesis of ADMA and SDMA may be increased through high protein-turnover in patients in a catabolic state and reduced renal clearance as a consequence of acute kidney injury. Differences in the relative concentrations of these methylarginines reflect their differential metabolism by DDAH isoforms as only ADMA is a DDAH substrate. Note, monomethylarginine (L-NMMA) is considered to have the same synthetic pathway, activity, metabolism and clearance as ADMA but is present in only 10% of the concentration

Within the cell, ADMA is tightly regulated by the two isoforms of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH1 and DDAH2) that hydrolyse the two active methylarginines to methylamines and L-citrulline [24, 25]. Only around 10% of ADMA is cleared by the kidney in normal conditions [26]. In contrast, SDMA is not metabolised by DDAH and is largely cleared by the kidney. The two isoforms of DDAH have similar structure but arise from different genetic loci and are expressed in differing tissue distributions [24]. SNPs of the DDAH2 gene have been associated with disease severity and/or progression in a number of disease states including hypertension [27], myocardial infarction [28] and chronic renal failure [29].

The production of NO in sepsis is regulated by a number of different processes in addition to the level of expression of NOS isoforms. These include changes in substrate and co-factor bioavailability, and cellular concentrations of ADMA, which competes with L-arginine binding to the NOS isoforms to regulate NO production. ADMA concentrations are regulated by the DDAH enzymes and their expression in different tissues may suggest differential roles in regulating the inflammatory response. The DDAH2 gene is located in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)III region of chromosome 6 and DDAH2 is the only isoform found in immune cells [24]; DDAH1 by contrast, the gene that is found on chromosome 1, is an important regulator of vascular function and has been shown to modulate the haemodynamic response in animal models of sepsis [30, 31]. These observations have led to the suggestion that DDAH2-mediated regulation of ADMA concentration may play a role in NO mediated inflammatory conditions [32] such as septic shock.

We undertook a secondary analysis of samples and clinical data from the Vasopressin versus noradrenaline as initial therapy in septic shock (VANISH) trial, which was a randomised controlled trial of two vasoactive treatments in septic shock. Our study tested the hypothesis that ADMA has a mechanistic role in determining outcome from septic shock and that the polymorphism of the DDAH2 promoter (rs805305) may impact on methylarginine metabolism and outcome in these patients.

Methods

In the VANISH trial, adult patients with septic shock, from 18 centres in the UK were recruited within a maximum of 6 h after the onset of hypotension to participate in a double-blind randomised controlled trial of vasopressin versus norepinephrine as the first-line treatment of vasopressor-dependent septic shock. The study was a 2 × 2 design with patients in each group randomised to receive placebo or hydrocortisone in addition to their primary intervention drug in the event that they did not respond adequately to study drug monotherapy. The study received ethics committee approval (Oxford A research ethics committee (12/SC/0014)) and was registered prior to the start of recruitment (ISRCTN20769191). Extensive clinical data were collected at baseline and on a daily basis up to day 28 after randomisation. The detailed protocol for this study and the primary outcome has been published previously [33, 34].

In 16 of the participating centres, local research teams were able to collect serial blood samples for subsequent analysis. Samples were collected at up to four time points during the study, after randomisation but prior to starting study drug (time point 0), and on study days 3, 5 and 7 thereafter.

Whole blood was collected in a 10-ml EDTA tube and immediately stored on ice. Within 15 min of sampling, the tube underwent centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 min. At the end of this period, plasma and buffy-coat aliquots were collected in separate cryotubes, labelled appropriately and immediately stored at − 80 °C. If staffing levels out of hours prevented sample processing, whole blood was stored for subsequent DNA analysis only.

Samples were analysed en bloc at the end of the study period. Methylarginine and L-arginine concentrations were analysed using an established high-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry approach [30, 35, 36]. In brief, samples were defrosted on ice and a 100-μL aliquot of plasma was collected and a known concentration of deuterium-labelled [7] ADMA standard was added. Following protein precipitation with methanol, the solution underwent centrifugation at 16000 rcf for 10 min. The supernatant was then dried and the residue re-suspended in mobile phase (0.1% formic acid) for analysis. A standard curve of ADMA, SDMA and L-arginine samples of 10 known concentrations was prepared (0–10 μM).

The presence of the rs805305 SNP in the DDAH2 gene was determined using genomic DNA extraction from buffy coat and whole blood samples by LGC group (Hertfordshire, UK). In a parallel experiment, the genotype of eight polymorphisms of the DDAH1 gene was also determined (Additional file 1: Table S5). Genotyping was undertaken using a proprietary competitive allele-specific PCR technique known as Kompetitive Allele Specific (KASP) PCR genotyping system which has been extensively used for uniplex SNP analysis [37, 38]. Additional quality-control criteria included interplate and intraplate duplicate testing and clear separation of signal clusters.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Prism software package (GraphPad Inc., CA, USA) and SPSS v25 (IBM plc, USA). Normally distributed data were analysed using the t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test comparison of groups as appropriate. Non parametric data were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare two groups or Kruskall-Wallis analysis for multiple groups, with Dunn’s multiple comparison test undertaken to compare differences between the groups. Survival was analysed by the log rank test to determine mortality trends and multivariate Cox regression analysis was undertaken to consider potential for confounding by other clinical factors.

Results

Clinical population

Of the 408 patients included in the VANISH trial modified intention-to-treat analysis, 209 had buffy-coat samples and 75 had whole blood stored that was suitable for DNA extraction and genotype analysis. In 249 of those patients, at least one plasma sample was available for analysis of methylarginine and L-arginine concentrations. Peak methylarginine concentrations were defined as the highest value measured from available samples for each patient. In patients who did not survive for the full sample collection period, the peak value from the available timepoints was selected. Patients in this subgroup had similar baseline characteristics to those of the VANISH population as a whole and as there was no difference in the primary outcome of renal-failure-free days or mortality between the treatment groups in the VANISH trial, all patients were analysed together in this study (Additional file 1) [34]. In the population that underwent genotyping analysis, median (IQR) duration of shock was 47.5 (26.1–87.5) h.

Temporal pattern of L-Arginine and methylarginines in septic shock

Plasma L-arginine and methylarginine concentrations were measured at each available time point and temporal patterns analysed (Table 1). Median L-arginine concentration was at its lowest on study inclusion then rose over subsequent study days (Fig. 2a). ADMA concentrations were elevated over normal plasma values [39] and median plasma ADMA concentration increased over the course of the study period (p < 0.001) and was significantly higher on days 5 and 7 than at study inclusion (all p < 0.05, (Fig. 2b). No significant changes in plasma SDMA concentration were observed during the study period, p = 0.478 (Additional file 1: Figure S1A).

Temporal patterns in L-arginine and methylarginines over time in septic shock. Plasma L-arginine (a), asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) (b) concentration changes over the first 7 days of inclusion in the VANISH trial; notation describes the number of samples available for analysis at each time point. Median and interquartile range plotted in red (both p < 0.001 over the time course (analysis of variance). Kaplan-Meier analysis of the association between methylarginine concentrations and outcome over time in septic shock following inclusion in the VANISH trial. A higher peak plasma ADMA (c) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) (d) concentration is associated with reduced survival in patients with septic shock. Data presented in quartiles (black line - top 25%, small-dotted grey line - 2nd quartile, dashed grey line - 3rd quartile, solid grey line - lowest quartile)

The impact of treatment group allocation on L-arginine and methylarginine concentrations was determined in order to rule out any treatment group effect. No differences were detected in plasma L-arginine or methylarginine concentrations across treatment allocations (Additional file 1: Table S1).

L-arginine and methylarginine concentrations and outcome

Median (IQR) L-arginine concentrations were similar in both survivors and non-survivors at recruitment and on day 3. A pattern of higher L-arginine concentration was, however, associated with non-survivors on days 5 and 7 (Additional file 1: Table S2, Figure S1B).

Plasma concentrations of ADMA and SDMA were elevated at each time point in patients who died compared to survivors (Additional file 1: Table S3 and S4, Figure S1C and S1D, respectively). Peak ADMA and SDMA levels were also elevated in non-survivors (2.73 (2.14–3.52) μM vs 1.98 (1.45–2.64) μM, p < 0.001 and 2.727 (2.14–3.52) μM vs 1.98 (1.45–2.64) μM), p < 0.001), respectively. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (SE) for peak ADMA concentration over the study period was 0.705 (0.63–0.78) ) (p < 0.001) and for SDMA it was 0.641 (0.56–0.73) (p < 0.001). The survival analysis showed that mortality rates increased with increasing concentrations of ADMA and SDMA (Fig. 2c and d, both p < 0.001). ADMA concentration in the upper 50% of values was independently associated with mortality in multivariate analysis including SDMA, age, sex, L-arginine and serum creatinine concentration as covariates (hazard ratio 1.82 (1.05–3.14), p = 0.033) (Table 2). The ADMA:arginine ratio displayed a similar pattern in the time course studied, with an increased ratio seen on day 3 (p = 0.004) and a similar trend on day 7 (p = 0.20). (Additional file 1: Figure S1E).

The impact of the rs805305 and eight DDAH1 SNP polymorphisms on outcome in septic shock

The plasma ADMA concentration was corrected for SDMA concentration as a marker of global DDAH activity. Lower DDAH activity was associated with improved survival on log rank analysis (p = 0.033) (Fig. 3a).

Associations between the rs805305 SNP of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH)2 promoter region and DDAH activity and outcome in septic shock. a Lower DDAH activity is associated with improved outcome in septic shock. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA):symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) ratio was employed as a marker of DDAH activity. Black line - patients with the lowest activity, dotted grey line - 2nd quartile, dashed grey line - 3rd Quartile, solid grey line – highest-activity quartile. The rs805305 SNP of the promoter region of the DDAH2 gene was sequenced in 284 participants in the VANISH trial. b Kaplan-Meier analysis of the impact of rs805305 SNP on 28-day survival in septic shock. The presence of the rare G:G homozygote (13.9%) was associated with improved survival compared to the common C:C homozygote (44.7), p = 0.02. Mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (c) and shock duration (d) were lower in patients expressing the less common G:G genotype than the common C:C expression pattern, p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively (analysis of variance)

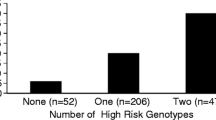

The rs805305 SNP of the DDAH2 promoter region was genotyped. The C:C genotype was seen in 128 (44.7%); the C:G heterozygote in 112 (39.1%) and the homozygote G:G haplotype in 40 (13.9%) The G minor allele of the rs805305 SNP was associated with significantly lower 28-day mortality (31% in the common wild-type C:C genotype, 22% in the C:G heterozygotes and 15% in the less common G:G group, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3b). Mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score during the study period was significantly reduced in patients with the G:G genotype (median (IQR) 4.1 (3.25–5.8)) compared to the heterogozygotes (5.0 (3.4–7.2)) and the common C:C genotype (5.2 (3.8–7.7), p = 0.04) (Fig. 3c). ANOVA revealed that duration of shock was also reduced in the G:G genotype (37 (23–79) h) compared to 46 (23–76) h in C:G heterozygotes and 53 (32–109) h in C:C genotype patients (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3d). Hospital length of stay displayed a similar pattern, with length of stay of 15.0 (11.0–47.0), 17 (8.25–35.0) and 19 (8.75–40.5) days in the G:G, C:G and C:C groups respectively, although this trend was not statistically significant (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The plasma ADMA:SDMA ratio was also examined in patients with each of the three genotypes of the rs805305 SNP. In the less common G:G homozygotes the median (IQR) ADMA:SDMA ratio was 1.0 (0.69–1.96), in the C:G heterozygotes it was 0.68 (0.51–0.95) and in the common C:C genotype it was 0.64 (0.40–0.91) (p = 0.004) (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Homozygotes for the less common DDAH1 SNPs genotyped were found in approximately 1% of the study population. No association with outcome was observed when the risk of death for those expressing the common homozygote genotype was compared to a combined group of heterozygotes and rare homozygotes of each SNP (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Discussion

This study validates in septic shock the observation made in heterogeneous groups with sepsis that elevated plasma ADMA concentration is associated with outcome. In addition, for the first time, we make the observation that a promoter polymorphism of the DDAH2 gene, rs805305 is associated with reduced DDAH activity, and in turn improved outcomes in septic shock.

The role of NO in the progression of the inflammatory response in patients with sepsis is complex, with essential upregulation of NO production facilitating appropriate vascular, cardiac and immune responses to pathogenic invasion. However, dysregulation of NO synthesis is a cardinal feature of septic shock and understanding how endogenous inhibitors of NOS enzymes and the genes that regulate them contribute to outcome in sepsis offers the potential for risk stratification and therapeutic development in an area of considerable unmet clinical need.

This is the largest study undertaken to date of methylarginine and L-arginine flux in septic shock and builds on previous work associating ADMA concentrations with outcome. By including only patients with established septic shock in this study, we were able to limit the heterogeneity seen in other studies in which sepsis and severe sepsis diagnoses were also included.

Our findings confirm the observations of a meta-analysis of 192 patients with sepsis, which concluded that L-arginine concentration is significantly reduced in the first week of a septic insult [40], which may be an important anti-inflammatory mechanism and increases the impact of competitive inhibitors of NOS on NO synthesis. We also validated the observation from heterogeneous sepsis cohorts [19, 21, 41] that in sepsis, both plasma ADMA and SDMA are associated with poor outcome, with similar degrees of sensitivity and specificity. The relationship between arginine and ADMA concentrations has been proposed as a marker of NOS activity in vivo [23]. Increased ADMA concentrations coupled with reductions in arginine availability in sepsis change the relationship between substrate and competitive inhibitor concentrations leading to reductions in NO production. In this study we found that survivors may have had lower NOS activity after day 3 than those patients that did not survive to discharge from the ICU. This may be consistent with reduced severity of NO-mediated inflammatory response, and is predominantly driven by reductions in plasma L-arginine concentrations. The factors that regulate L-arginine availability are important regulators of the inflammatory response and merit further exploration in septic shock.

These data suggest for the first time in a robust human population with septic shock that an increased ADMA:SDMA ratio is associated with increased survival. This builds on animal and human data suggesting that the plasma ADMA:SDMA ratio may be a better reflection of DDAH enzyme activity than ADMA concentration alone [42, 43]. This reflects the observation that using the circulating ADMA concentration as a marker of DDAH activity is confounded by changes in protein turnover and renal function in acute disease states. Correcting ADMA for SDMA concentration may eliminate this confounder because SDMA handling will be similarly affected by protein turnover and renal failure. Since it is not metabolised by DDAH isoforms, any changes in the relative proportions of ADMA and SDMA is likely to be driven by changes in DDAH activity.

This study shows that in those patients with lower DDAH activity, the resultant increased intracellular ADMA concentrations may confer a survival advantage during an acute disease process such as sepsis by modulating the acute production of excess NO. This is in contrast to plasma ADMA measurement alone and also may reflect a different physiological effect of ADMA in sepsis to that seen in chronic disease states where persistent elevation of intracellular ADMA may be deleterious [44,45,46]. Previous transgenic animal models have suggested that global and macrophage-specific knockout DDAH2 is associated with poor outcomes in murine models of sepsis [35]. This contrasts with the observations in this study and may reflect the difference between the complete abolition of DDAH2 activity seen in knockout models compared to the modulation of enzyme activity typically seen with functional polymorphisms.

The rs805305 SNP has been examined in pilot studies in sepsis and been associated with plasma ADMA and inflammatory cytokine expression [19, 21, 41]. It has also been associated with the development of hypertension in other populations [47]. Here we show for the first time that the rs805305 SNP is associated with reduced DDAH activity and survival in septic shock. This small study of a genetic association with outcome in septic shock offers insights into the role of endogenous regulators of NO synthesis. Future work will focus on validating this observation and understanding the potential for DDAH2 modulation as therapy in septic shock.

Limitations of this study include a possible bias introduced by using patients included in a randomised controlled trial. The use of results, plasma and DNA from the VANISH trial enabled high-quality data collection in multiple centres that does, however, confer a significant advantage in translational studies of this kind over small, single-centre observational studies. The combination of approaches utilised in this study gives confidence in its conclusions; however, further validation of the role of the rs805305 polymorphism in septic shock in a further data set would be valuable.

Future work should focus on the potential effect of therapeutic modulation of DDAH activity as a whole and DDAH2 specifically merits exploration in septic shock, with the ADMA:SDMA ratio offering an attractive marker of therapeutic efficacy [31].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study is the largest yet conducted exploring the associations between DDAH activity and outcome in septic shock. We confirmed the observation that both plasma ADMA and SDMA are associated with outcome. We showed for the first time using the ADMA:SDMA ratio that reduced DDAH activity is associated with improved survival and that the rs805305 SNP of the DDAH2 promoter region is associated with both reduced DDAH activity and improved survival.

Abbreviations

- ADMA:

-

Asymmetric dimethylarginine

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- DDAH:

-

Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KASP:

-

Kompetitive allele specific

- LNMMA:

-

Monomethylarginine

- MA:

-

Methylarginine

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- SDMA:

-

Symmetric dimethylarginine

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- VANISH:

-

Vasopressin versus noradrenaline as initial therapy in septic shock

References

Marshall JC. Sepsis: rethinking the approach to clinical research. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:471–82.

Shankar-Hari M, Bertolini G, Brunkhorst FM, Bellomo R, Annane D, Deutschman CS, Singer M. Judging quality of current septic shock definitions and criteria. Crit Care. 2015;19:1–5.

Vincent JL, Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1726–34.

Vincent JL, Gris P, Coffernils M, Leon M, Pinsky M, Reuse C. Myocardial depression characterizes the fatal course of septic shock. Surgery. 1992;111:660–7.

Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–51.

De Backer D, Creteur J, Preiser J-C, Dubois M-J, Vincent J-L. Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:98–104.

Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. What is the best method for estimating the burden of severe sepsis in the United States? J Crit Care. 2012;27:414.e1–9.

Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NKJ, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, Angus DC, Reinhart K. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;193:259–72.

Arnalich F, Hernanz A, Jiménez M, López J, Tato E, Vázquez JJ, Montiel C. Relationship between circulating levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide, nitric oxide metabolites and hemodynamic changes in human septic shock. Regul Pept. 1996;65:115–21.

Cauwels A. Ntric Oxide in septic shock. Kidney Int. 2007;72:557–65.

Endo S, Inada K, Nakae H, Arakawa N, Takakuwa T, Yamada Y, Shimamura T, Suzuki T, Taniguchi S, Yoshida M. Nitrite/nitrate oxide (NOx) and cytokine levels in patients with septic shock. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1996;91:347–56.

Lopez A, Lorente J, Steingrub J, Bakker J, McLuckie A, Willatts S, Brockway M, Anzueto A, Holzapfel L, Breen D. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:21–30.

Nathan C, Xie QW. Regulation of biosynthesis of nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13725–8.

Leone A, Moncada S, Vallance P, Calver A, Collier J. Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet. 1992;339:572–5.

McBride AE, Silver PA. State of the Arg: protein methylation at arginine comes of age. Cell. 2001;106:5–8.

Meyer J, Richter N, Hecker M. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of nitric oxide synthase-related arginine derivatives in vitro and in vivo. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:11–6.

Schnabel R, Blankenberg S, Lubos E, Lackner KJ, Rupprecht HJ, Espinola-Klein C, Jachmann N, Post F, Peetz D, Bickel C, Cambien F, Tiret L, Münzel T. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and the risk of cardiovascular events and death in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the AtheroGene Study. Circ Res. 2005;97:e53–9.

Caplin B, Nitsch D, Gill H, Hoefield R, Blackwell S, MacKenzie D, Cooper JA, Middleton RJ, Talmud PJ, Veitch P, Norman J, Wheeler DC, Leiper JM. Circulating methylarginine levels and the decline in renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease are modulated by DDAH1 polymorphisms. Kidney Int. 2009;77:459–67.

O'Dwyer M, Dempsey F, Crowley V, Kelleher D, McManus R, Ryan T. Septic shock is correlated with asymmetrical dimethyl arginine levels, which may be influenced by a polymorphism in the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase II gene: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2006;10:R139.

Tea B. L-arginine and asymmetric dimethylarginine are early predictors for survival in septic patients with acute liver failure. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:11.

Davis JS, Darcy CJ, Yeo TW, Jones C, McNeil YR, Stephens DP, Celermajer DS, Anstey NM. Asymmetric dimethylarginine, endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability and mortality in sepsis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17260.

Mortensen KM, Itenov TS, Haase N, Müller RB, Ostrowski SR, Johansson PI, Olsen NV, Perner A, Søe-Jensen P, Bestle MH. High levels of methylarginines were associated with increased mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Shock. 2016;46:365–72.

Winkler MS, Kluge S, Holzmann M, Moritz E, Robbe L, Bauer A, Zahrte C, Priefler M, Schwedhelm E, Böger RH, Goetz AE, Nierhaus A, Zoellner C. Markers of nitric oxide are associated with sepsis severity: an observational study. Crit Care. 2017;21:189.

Leiper JM. Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochem J. 1999;343:209–14.

Tran CT, Fox MF, Vallance P, Leiper JM. Chromosomal localization, gene structure, and expression pattern of DDAH1: comparison with DDAH2 and implications for evolutionary origins. Genomics. 2000;68:101–5.

Tran CTL, Leiper JM, Vallance P. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway. Atheroscler Suppl. 2003;4:33–40.

Seoa H-A, Kima S-W, Jeona E-J, Jeonga J-Y, Moonb S-S, Leed W-K, Kima J-G, Leea c I-K, Park K-G. Association of the DDAH2 gene polymorphism with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98:125–31.

Pérez-Hernández N, Vargas-Alarcón G, Arellano-Zapoteco R, Martínez-Rodríguez N, Fragoso JM, Aptilon-Duque G, Posadas-Sánchez R, Posadas-Romero C, Juárez-Cedillo T, Domínguez-López ML, Rodríguez-Pérez JM. Protective role of DDAH2 (rs805304) gene polymorphism in patients with myocardial infarction. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;97:393–8.

Marra M, Marchegiani F, Ceriello A, Sirolla C, Boemi M, Franceschi C, Spazzafumo L, Testa I, Bonfigli AR, Cucchi M, Testa R. Chronic renal impairment and DDAH2-1151 A/C polymorphism determine ADMA levels in type 2 diabetic subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:964–71.

Leiper J, Nandi M, Torondel B, Murray-Rust J, Malaki M, O’Hara B, Rossiter S, Anthony S, Vallance P. Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nat Med. 2007;13:198–203.

Wang Z, Lambden S, Taylor V, Sujkovic E, Nandi M, Tomlinson J, Dyson A, McDonald N, Caddick S, Singer M, Leiper J. Pharmacological inhibition of DDAH1 improves survival, hemodynamics and organ function in experimental septic shock. Bichem J. 2014;460:309–16.

Lambden S, Martin D, Tomlinson J, Mythen M, Leiper J. Role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 in the regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in animal and observational human models of normobaric hypoxia. Lancet. 2016;387:S62.

Gordon AC, Mason AJ, Perkins GD, Ashby D, Brett SJ. Protocol for a randomised controlled trial of vasopressin versus noradrenaline as initial therapy in septic shock (VANISH). BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005866.

Gordon AC, Mason AJ, Thirunavukkarasu N, et al. Effect of early vasopressin vs norepinephrine on kidney failure in patients with septic shock: the vanish randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:509–18.

Lambden S, Kelly P, Ahmetaj-Shala B, Wang Z, Lee B, Nandi M, Torondel B, Delahaye M, Dowsett L, Piper S, Tomlinson J, Caplin B, Colman L, Boruc O, Slaviero A, Zhao L, Oliver E, Khadayate S, Singer M, Arrigoni F, Leiper J. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 regulates nitric oxide synthesis and hemodynamics and determines outcome in polymicrobial sepsis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1382–92.

Tomlinson JAP, Caplin B, Boruc O, Bruce-Cobbold C, Cutillas P, Dormann D, Faull P, Grossman RC, Khadayate S, Mas VR, Nitsch DD, Wang Z, Norman JT, Wilcox CS, Wheeler DC, Leiper J. Reduced renal methylarginine metabolism protects against progressive kidney damage. JASN. 2015;26(12):3045–59.

Semagn K, Babu R, Hearne S, Olsen M. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP): overview of the technology and its application in crop improvement. Mol Breed. 2013;33:1–14.

Levinsson A, Olin A-C, Björck L, Rosengren A, Nyberg F. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) single nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with coronary heart disease and hypertension in the INTERGENE study. Nitric Oxide. 2014;39:1–7.

Leiper J, Vallance P. Biological significance of endogenous methylarginines that inhibit nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:542–8.

Davis JS, Anstey NM. Is plasma arginine concentration decreased in patients with sepsis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:380–5.

Weiss SL, Haymond S, Ranaivo HR, Wang D, De Jesus VR, Chace DH, Wainwright MS. Evaluation of asymmetric dimethylarginine, arginine, and carnitine metabolism in pediatric sepsis. Paediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e210–8.

Umbrello M, Pavini FC, Bolgiaghi L, Carloni E, Rapido F, Gomarasca M, D'Angelo E, Iapichino G. Asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines: metabolism and role in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13:P361.

Carello KA, Whitesall SE, Lloyd MC, Billecke SS, D'Alecy LG. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine plasma clearance persists after acute total nephrectomy in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H209–16.

Boger R. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a novel risk marker in cardiovascular medicine and beyond. Ann Med. 2006;38:126–36.

Böger RH, Endres HG, Schwedhelm E, Darius H, Atzler D, Lüneburg N, von Stritzky B, Maas R, Thiem U, Benndorf RA, Diehm C. Asymmetric dimethylarginine as an independent risk marker for mortality in ambulatory patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Intern Med. 2011;269:349–61.

Willeit P, Freitag DF, Laukkanen JA, Chowdhury S, Gobin R, Mayr M, Di Angelantonio E, Chowdhury R. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and cardiovascular risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 prospective studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001833.

Maas R, Erdmann J, Lüneburg N, Stritzke J, Schwedhelm E, Meisinger C, Peters A, Weil J, Schunkert H, Böger RH, Lieb W. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 gene are associated with prevalence of hypertension. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:488–93.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the recruitment sites for their efforts in collecting and preparing samples for the subsequent analysis and the research team at Imperial College NHS trust for their support in the conduct of this study.

Funding

This VANISH trial was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit programme (grant number PB-PG-0610-22,350) and an NIHR Clinician Scientist Award held by Dr. Gordon. Infrastructure support was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. MRC intramurual funding, BJA/RCoA NIAA project grant. ACG is an NIHR Research Professor. SL is an NIHR Clinical Lecturer.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in an online supplement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL participated in the design of the study, prepared samples for genotype analysis, performed measurements of NOx and methylarginine levels in biological samples and performed statistical analysis. SP and JT performed measurements of methyarginines in biological samples. AG and JL conceived the study and participated in the study design, interpretation of results and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethics committee approval (Oxford A research ethics committee (12/SC/0014)) and was registered prior to the start of recruitment (ISRCTN20769191).

Consent for publication

Patient consent was secured for participation in this study and publication of relevant results.

Competing interests

JL and SL are founding directors of and consultants to Critical Pressure ltd.

ACG reports that outside of this work he has received speaker fees from Orion Corporation Orion Pharma and Amomed Pharma. He has consulted for Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Tenax Therapeutics, Baxter Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb and GSK and received grant support from Orion Corporation Orion Pharma, Tenax Therapeutics and HCA International with funds paid to his institution.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Median (IQR) peak concentrations of L-arginine, ADMA and SDMA (μM) in patients with septic shock categorised by treatment arm in the VANISH trial; p value for Kruskall-Wallis test, no intergroup differences detected on Dunn’s multiple comparison testing. Table S2. Pattern of plasma L-arginine concentrations over the first 7 days of the VANISH trial in survivors and non-survivors. Median (IQR) concentrations (μM). Table S3. Pattern of plasma ADMA concentrations over the first 7 days of the VANISH trial in survivors and non-survivors. Median (IQR) concentrations (μM). Table S4. Pattern of plasma SDMA concentrations over the first 7 days of the VANISH trial in survivors and non-survivors. Median (IQR) concentrations (μM). Table S5. Relationship between eight intronic SNPs of DDAH1 and mortality in septic shock. The prevalence of the rare genotype in each of the eight DDAH1 SNPs was noted. The odds ratio of death at 28 days after study inclusion was calculated for the common homozygotes against the combined heterozygote and rare homozygote populations. No significant differences in outcome were observed between the groups expressing the less common alleles and the common homozygotes. Figure S1. Plasma concentrations of L-arginine (A), ADMA (B) and SDMA (C) in septic shock and association with survival. Plasma from 249 patients with septic shock enrolled in the VANISH trial was collected collection on inclusion into the trial, which was prior to the start of vasopressor therapy (Day 0), and on days 3, 5 and 7 of the study. Dot plot (with median (IQR) overlay in black (survivors) or red (non-survivors)) comparing plasma concentrations on study inclusion and on days 3, 5 and 7 after study inclusion in survivors and non-survivors at 28 days after admission with septic shock. Median (IQR) plasma L-arginine concentrations were similar in non-survivors at each time point. Plasma ADMA and SDMA concentrations were higher in non-survivors at each time point. D Plasma SDMA concentration changes over the first 7 days of inclusion in the VANISH trial, notation describes the number of samples available for analysis at each time point. Median and interquartile range plotted in red. E Dot plot (with median (IQR) overlay in black (survivors) or red (non-survivors)) comparing plasma ADMA:L-arginine concentrations on study inclusion and on days 3, 5 and 7 after study inclusion in survivors and non-survivors at 28 days after admission with septic shock. Median (IQR) plasma ADMA:L-arginine concentrations appeared higher in non-survivors at days 3,5 and 7. Figure S2. Association between the rs805305 SNP of the DDAH2 promoter region and outcome in septic shock. Presence of the rare G:G homozygote was associated with a trend towards reduced hospital length of stay but was not statistically significant. Figure S3. Association between the rs805305 SNP of the DDAH2 promoter region and DDAH activity and outcome in septic shock. Plasma ADMA:SDMA ratio was elevated in the rare G:G genotype compared to the common C:C expression pattern, p = 0.004. (DOCX 3485 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lambden, S., Tomlinson, J., Piper, S. et al. Evidence for a protective role for the rs805305 single nucleotide polymorphism of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH2) in septic shock through the regulation of DDAH activity. Crit Care 22, 336 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2277-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2277-5