Abstract

Introduction

Activation of the MAPK pathway by genetic mutations (such as BRAF and RET) initiates and accelerates the growth of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). However, the correlation between genetic mutations and clinical features remains to be established. Therefore, this study aimed to retrospectively analyze major genetic mutations, specifically BRAF mutations and RET rearrangements, and develop a treatment algorithm by comparing background and clinical characteristics.

Method

One hundred thirteen patients with primary PTC were included in this study. BRAF mutations were detected via Sanger sequencing and RET rearrangements were detected via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis, and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence of BRAF mutations and RET rearrangements and their clinical characteristics (age, sex, TNM, stage, extratumoral extension, tumor size, unifocal/multifocal lesions, vascular invasion, differentiation, chronic thyroiditis, preoperative serum thyroglobulin level, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake) were compared subsequently.

Result

After excluding unanalyzable specimens, 80 PTC patients (22 males and 58 females, mean age: 57.2 years) were included in the study. RET rearrangements were positive in 8 cases (10%), and BRAF mutation was positive in 63 (78.6%). The RET rearrangement group was significantly associated with younger age (p = 0.024), multifocal lesion (p = 0.048), distant metastasis (p = 0.025) and decreased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (p < 0.001). The BRAF mutation group was significantly associated with unifocal lesions (p = 0.02) and increased 18F-FDG uptake (p = 0.004).

Conclusion

In this study, an increase in M classification cases was found in the RET rearrangements group. However, genetic mutations were not associated with the clinical stage, and no factors that could be incorporated into the treatment algorithm were identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thyroid carcinoma, a malignancy of the endocrine system, can be classified into papillary, follicular, poorly differentiated, medullary, and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. The incidence of thyroid carcinoma increased worldwide over the past four decades [1]. Globally, in 2022, the age-standardized incidence rates of thyroid cancer were 13.6 per 100 000 women and 4.6 per 100 000 men [2]. Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), which originates from thyroid follicular cells, accounts for 85% of all cases of thyroid carcinoma. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for PTC, with a 10-year survival rate of 95% indicating a generally favorable prognosis [3]. Radioactive iodine therapy has been used for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic cases [4]. Multi-kinase inhibitors (MKI), such as lenvatinib and sorafenib, have been indicated for the treatment of iodine-refractory cases [5]. Lenvatinib and sorafenib extend the progression-free survival in international Phase III trials by 14.7 months (lenvatinib group: 18.3 months vs. placebo group: 3.6 months, hazard ratio [HR]: 0.21, 99% confidence interval [CI]: 0.14–0.31) and 5 months (sorafenib group: 10.8 months vs. placebo group: 5.8 months, HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.45–0.76), respectively [6, 7]. Subsequent clinical trials have also reported an extension in progression-free survival [8, 9]. However, options for subsequent treatment are limited for patients exhibiting resistance to MKIs. MKIs do not target a particular gene as an indicator for drug selection; however, molecularly targeted drugs that focus on genetic mutations have garnered interest as therapeutic options [3].

Recent advances in genetic analysis techniques have revealed the role of multiple gene mutations in the development and progression of thyroid carcinomas. Recent treatment strategies target genetic mutations that activate the MAPK pathway or PI3K pathway, such as RET, RAS, NTRK, and BRAF, in patients with PTC [10]. BRAF mutation is observed most frequently in patients with PTC, followed by RET rearrangements, RAS mutations, and NTRK mutations, which are mutually exclusive [10, 11]. Furthermore, The Cancer Genome Atlas proposed that PTC could be classified into two molecular subtypes based on transcriptomic characteristics, BRAF-like (BRAF V600E and RET/PTC rearrangements) and RAS-like (HRAS, NRAS, or KRAS). RAF-like PTC primarily activate the MAPK pathway and are more aggressive than RAS-like PTC [12, 13]. Thus, previous studies have revealed an association between gene mutations and malignancy and prognosis; however, there are not enough studies that have conducted a comprehensive gene analysis of all types of thyroid carcinoma, including lesions that have undergone treatment. Furthermore, guidelines for the treatment or clinical outcomes in this context remain to be established, and indications for genetic testing are not clearly indicated.

Therefore, this study aimed to retrospectively analyze the major genetic mutations, BRAF mutations, and RET rearrangements, and develop a treatment algorithm by comparing patient backgrounds and clinical characteristics.

Materials and methods

Patients and tumor samples

One-hundred-thirteen patients with PTC who had undergone thyroidectomy at the Otorhinolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery Department of Kanazawa University Hospital between April 2021 and March 2024 were included in this study. Patients with primary lesions were eligible for inclusion. PTC was diagnosed by pathologists at the Kanazawa University Hospital using tissue slides obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of PTC tissues including primary of thyroid carcinomas. Seven cases were excluded owing to difficulty in excision due to calcification or the small size of the tumor (< 1 mm). The remaining 106 patients underwent fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. This study was approved by the Investigational Review Board of Kanazawa University (approval no.114524).

Data analysis

The presence of BRAF mutation was identified via Sanger sequencing. RET rearrangements were comprehensively detected via FISH analysis, regardless of the partner gene. Furthermore, RET/PTC1, a representative RET rearrangement, was identified via RT-PCR. Patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of BRAF mutation and RET rearrangements. The following background and clinical characteristics of the patients were retrospectively examined: age, sex, TNM, stage, extratumoral extension (ex), tumor size, unifocal/multifocal lesions, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, differentiation, preoperative serum thyroglobulin levels, chronic thyroiditis, and 18F-FDG uptake. Tumor staging was performed according to the UICC for International Cancer Control TNM classification (eighth edition). A poorly differentiated carcinoma was defined as one that contains even a small amount of poorly differentiated components. We defined chronic thyroiditis as either a pre-existing condition noted before surgery or a condition identified pathologically from thyroid tissue surrounding the tumor.

RNA/DNA isolation

RNA and DNA were isolated from FFPE tissue slices of PTC using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Deparaffinization was performed using the Deparaffinization Solution (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using ReverTraAce qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). All procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

RET rearrangements reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

RET/PTC1 was amplified via nested polymerase chain reaction (nested PCR). Forward and reverse primers were set in the CCDC6 and tyrosine kinase regions, respectively [14]. Table 1 presents the primer sequences. The cDNA, primers, and Master Mix (KOD One PCR Master Mix Blue TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) were adjusted, and PCR was performed as follows: First PCR: one cycle at 98℃ for 2 min, 30 cycles of denaturation (98℃ for 10 s), annealing (56℃ for 5 s), and extension (68℃ for 5 s). Second PCR: one cycle at 98℃ for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation (98℃ for 10 s), annealing (55℃ for 5 s), and extension (68℃ for 5 s). Electrophoresis was performed on 2% agarose gel to analyze the PCR products. The positive control for RET/PTC1 was created using a thyroid papillary carcinoma cell line that has the CCDC6-RET rearrangement. RNA extraction from the cell line was performed using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany).

BRAF mutation Sanger sequencing

PCR was performed to amplify exon 15 of the BRAF gene, which may contain the T1799A mutation (BRAFV600E). Table 1 presents the primer sequences [15].

The dsDNA, primers, and Master Mix (KOD One PCR Master Mix Blue TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) were adjusted, and PCR was performed as follows: one cycle at 95℃ for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation (95℃ for 30 s), annealing (60℃ for 30 s), and extension (72℃ for 40 s). Sanger sequencing was performed using an external DNA sequencing service (FASMAC, Kanagawa, Japan) to evaluate the purified PCR products.

FISH analysis

The ZytoLight FISH-Tissue Implementation Kit (ZytoVison GmbH, Bremerhaven, Germany) was used to perform tissue preparation, including deparaffinization and proteolysis of 4-mm FFPE tissue slides. A ZytoLight SPEC RET Dual Color Break-Apart Probe (ZytoVison GmbH, Bremerhaven, Germany) was used to perform denaturation and hybridization. The cell nuclei were analyzed via fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The rearrangement and non-rearrangement patterns are evaluated for each nucleus. RET rearrangements exhibited one orange/green-fused signal and one separated orange/green signal per nucleus. The cut-off for the separation distance was set at ≥ 2 signal strengths.

Non-rearrangements exhibit two orange/green-fused signals per nucleus. Fifty nuclei were counted. Nuclei with RET fusion genes in ≥ 15% of the nuclei were defined as RET rearrangement-positive [14, 16].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics software version 27.0.1(IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). The patients were assigned to two groups based on the presence or absence of RET rearrangement and BRAFV600E mutation, respectively. Cases in which genetic evaluation was difficult were excluded from the allocation. Patient backgrounds and clinical characteristics were compared subsequently. Continuous variables were evaluated using Welch’s t-test. Nominal variables were evaluated using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Eighty patients with PTC, excluding specimens that were deemed unanalyzable, were included in the present study. Total resection was performed in 24 cases and partial resection in 56 cases. Table 2 summarizes the background and clinical characteristics of all patients. The study cohort comprised 22 males and 58 females (mean age: 57.2 years). The tumor stages were T1–2 and T3–4 in 59 and 21 cases, respectively. The lymph node status was N0 and N1 in 39 and 41 cases, respectively. Missing values were noted for vascular invasion, tumor size, preoperative serum thyroglobulin levels, and 18F-FDG uptake.

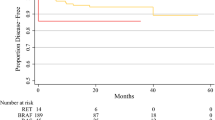

RET rearrangements and clinical characteristics

Figures 1 and 2 present representative images of RET rearrangements of the PCR products determined via FISH and gel electrophoresis. Factors, such as absent or weak fluorescence, hindered the evaluation for 26 cases. FISH revealed RET rearrangements in eight (10%) of the 80 cases. PCR revealed RET rearrangement in two cases. PCR-positive cases were not observed among the FISH-negative cases. Patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of RET rearrangements, and the clinical characteristics were compared subsequently (Table 3). The RET rearrangement group was significantly associated with younger age (40.3 ± 18.5 vs 60.0 ± 15.7 p = 0.024), an increase in the number of multifocal lesions cases (p = 0.048), distant metastasis (M classification p = 0.025) and the decreased 18F-FDG uptake (4.28 ± 1.76 vs 15.8 ± 14.6 p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of sex, TN classification, stage, EX, vascular invasion, differentiation, chronic thyroiditis, tumor size, or preoperative thyroglobulin levels.

RET rearrangements visualized via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). A and B present FISH-positive samples. RET rearrangements exhibit one orange/green fusion signal (indicated by a red circle), one orange signal, and one separate green signal (indicated by a yellow circle) per nucleus. C and D present FISH-negative samples. Non-rearrangements exhibit two orange/green-fused signals per nucleus. Fifty nuclei were counted. Nuclei with RET fusion genes in ≥ 15% were defined as RET rearrangement-positive

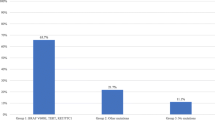

BRAF mutation and clinical characteristics

Figure 3 presents the results of BRAFV600E Sanger sequencing analysis. Two cases could not be evaluated owing to as it could not be amplified. (FISH analysis was also not available for these two cases.) Sixty-three (78.6%) of the 80 cases were positive. BRAF mutation was observed in one patient in the RET rearrangement-positive group (eight cases). These two genetic mutations are considered mutually exclusive, increasing the possibility of false positives [12]. Patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of BRAF mutations and compared their clinical characteristics (Table 3). A significant increase in the number of unifocal lesion cases (p = 0.02) and 18F-FDG uptake was observed in the BRAF mutation-positive group (17.0 ± 15.0 vs 6.33 ± 6.80, p = 0.004). No significant differences were found for other factors.

Chronic thyroiditis could be a factor affecting 18F-FDG uptake, so an additional T-test was performed on the presence or absence of chronic thyroiditis and 18F-FDG uptake. There was no significant difference between the two groups (12.4 ± 7.56 vs 15.3 ± 15.5, p = 0.452).

Discussion

According to the conventional perspective on the pathogenesis of thyroid carcinoma, these lesions develop owing to the accumulation of mutations, which propel progression through an initial dedifferentiation process that results in the formation of well-differentiated carcinomas, namely papillary and follicular carcinomas [17]. Several genetic alterations contributing to most subtypes of thyroid carcinoma have been identified. These alterations predominantly affect the components of the principal oncogenic pathways, such as the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, which are involved in signal transduction from receptor tyrosine kinases. Thus, these pathways play a crucial role in cell survival and proliferation and are primarily regulated by external growth factors supplied by the surrounding cells. Genetic mutations result in the dysregulated activation of these pathways, leading to tumor formation [18]. Activation of the MAPK pathway plays a key role in the development of PTC and involves BRAF mutations, RET rearrangements, and NTRK fusion genes [19].

The binding of RET to another gene via chromosomal rearrangements leads to RET rearrangements, yielding several types of RET rearrangements depending on the partner gene. Over 30 types have been reported to date. RET/PTC1 (CCDC6-RET) and RET/PCT3 (NCOA4-RET) account for 90% of RET rearrangements in patients with PTC [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Recent clinical data suggest a positivity rate of 10–20% [11, 26], with some recent reports indicating a decline in prevalence [27]. A large cohort study published in 2014 reported a prevalence rate of 6.8% [12]. RET rearrangements were observed in eight of the 80 patients (10%) in the present study, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports. In our study, a significant difference in the clinical characteristics was observed with respect to younger age, an increased number of multifocal lesions distant metastasis and decreased 18F-FDG uptake. Significant differences in age, multifocal lesions, and distant metastasis were consistent with previous reports [14, 28, 29]. On the other hand, no correlations with, lymph node metastasis, or extrathyroidal extension were observed, as reported in previous studies. This may be attributed to the small number of cases. Moreover, the iodine uptake rate could not be evaluated comprehensively owing to insufficient data. No previous study has investigated the association between 18F-FDG uptake and RET rearrangements. A study on the diagnostic efficacy of 18F-FDG-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) for recurrent medullary carcinoma reported a sensitivity and specificity of 17–95% and 68–100%, respectively, which limited the utility of 18F-FDG-PET/CT [30, 31]. As discussed below, the mechanism of 18F-FDG accumulation is complex and further research is needed to elucidate it.

T1799A transversion mutation in exon 15, which results in the substitution of valine at position 600 with glutamic acid (BRAFV600E), is the most commonly observed BRAF mutation in thyroid carcinoma. This substitution activates BRAF, which subsequently activates the MAPK pathway [32, 33]. BRAF mutations have been detected in 29–83% of cases of PTC [34,35,36]. BRAF mutation is associated with extrathyroidal extension, advanced TNM stage, lymph node metastasis, multifocality, and recurrence [37,38,39,40]. The prevalence of BRAF mutations was 78.6% in the present study, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [41, 42]. BRAF mutations are associated with an increase in the number of unifocal lesions and elevated 18F-FDG uptake. The findings pertaining to the unifocal lesions contradicted those of previous reports. Many previous studies focused on cases where total thyroidectomy was performed. In this study, partial thyroidectomy accounted for 70% of the cases, which may have influenced the results [43, 44].

There are studies suggesting that BRAF mutations influence the increase in 18F-FDG uptake. Generally, FDG uptake is correlated with the expression of GLUT1, and the MAPK pathway promotes the expression of GLUT1. Therefore, it has been considered that FDG uptake increases in BRAF mutation-positive PTC. However, there are also reports suggesting that GLUT1 expression does not correlate with FDG accumulation, and other reports indicate an association with GLUT3, GLUT4, HIF1α, and YAP signaling. Additionally, BRAF mutations have been suggested to be associated with increased expression of HIF1α. Thus, the mechanisms of FDG accumulation in tumor tissues are not yet fully understood, and further research is needed [45,46,47,48,49].

The role of genetic testing in thyroid carcinoma is considered complementary. Next-generation sequencing methods can be used to detect gene mutations; however, the prognosis for many patients with PTC is favorable. A consensus regarding when and in which cases genetic testing should be conducted remains to be established. The 2015 ATA Guidelines recommend confirming the presence of genetic mutations (BRAF, RET/PTC, RAS, PAX8/PPARγ) in cases that are difficult to differentiate or assess via cytological examinations [50]. The 2023 NCCN guidelines recommend conducting genetic testing for patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma when considering treatment. A combination therapy of a BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) and MEK inhibitor (trametinib) or RET inhibitors (selpercatinib or pralsetinib) is recommended based on the mutation detected [51]. Studies are also underway to expand the indications of these molecular-targeted drugs for the treatment of PTC [52, 53].

The present study investigated the prevalence of BRAF mutations and RET rearrangements in PTC, as well as the clinical characteristics contributing to the treatment algorithm. There was an increase in distant metastasis cases in the RET rearrangement group, but this did not affect stage. No significant associations were observed between the presence of genetic mutations and other factors such as TN stage elevation or thyroid gland invasion that could be incorporated into risk classification or treatment algorithms for thyroid carcinoma. Furthermore, specific features that warranted genetic testing could not be identified. Genetic mutations may not be directly associated with malignancy; however, the combined prevalence of BRAF mutations and RET rearrangements was high (87.5%), indicating that cases with genetic mutations targeted by molecular-targeted drugs exist widely, regardless of the clinical stage. Thus, genetic testing should be performed whenever possible, particularly when treating patients with recurrent metastases. The importance of genetic mutations is expected to increase and their application in treatment will further advance as genetic testing becomes more widespread.

Conclusion

This study revealed the presence of RET rearrangements and BRAF mutations in 80 patients with PTC and compared their clinical features based on the genetic status in 87.5% of cases. In this study, an increase in M classification was found in the RET rearrangements group. However, distant metastases accounted for 3.8% of all cases, and the presence or absence of genetic mutations was not associated with the clinical stage, and no items that could be incorporated into the treatment algorithm were identified.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PTC:

-

Papillary thyroid carcinoma

- MKI:

-

Multi-kinase inhibitors

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Kitahara CM, Schneider AB. Epidemiology of Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31(7):1284–97. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-1440.

Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834.

Fagin JA, Wells SAJ. Biologic and Clinical Perspectives on Thyroid Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1054–67. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1501993.

Tang J, et al. The role of radioactive iodine therapy in papillary thyroid cancer: an observational study based on SEER. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3551–60. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S160752.

Koehler VF, et al. Real-World Efficacy and Safety of Multi-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Radioiodine Refractory Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2021;31(10):1531–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2021.0091.

Schlumberger M, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621–30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406470.

Brose MS, et al. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2014;384(9940):319–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60421-9.

Hamidi S, et al. Lenvatinib Therapy for Advanced Thyroid Cancer: Real-Life Data on Safety, Efficacy, and Some Rare Side Effects. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(6):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac048.

Kim M, et al. Lenvatinib Compared with Sorafenib as a First-Line Treatment for Radioactive Iodine-Refractory, Progressive, Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: Real-World Outcomes in a Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2023;33(1):91–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2022.0054.

Nikiforov YE, Nikiforova MN. Molecular genetics and diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(10):569–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.142.

Pekova B, et al. NTRK Fusion Genes in Thyroid Carcinomas: Clinicopathological Characteristics and Their Impacts on Prognosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081932.

Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159(3):676–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050.

Lim J, et al. Different Molecular Phenotypes of Progression in BRAF- and RAS-Like Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul, Korea). 2023;38(4):445–54. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2023.1702.

Musholt TJ, et al. Detection of RET rearrangements in papillary thyroid carcinoma using RT-PCR and FISH techniques - A molecular and clinical analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2019;45(6):1018–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.11.009.

Wang Z, Sun K, Jing C, Cao H, Ma R, Wu J. Comparison of droplet digital PCR and direct Sanger sequencing for the detection of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(6):e22902.

Liu Y, Wu S, Zhou L, Guo Y, Zeng X. Pitfalls in RET Fusion Detection Using Break-Apart FISH Probes in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):1129–38. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa913.

Haugen BR, Sherman SI. Evolving approaches to patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(3):439–55. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2012-1038.

Takahashi M. RET receptor signaling: Function in development, metabolic disease, and cancer. Proc Japan Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2022;98(3):112–25. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.98.008.

Prete A, Borges de Souza P, Censi S, Muzza M, Nucci N, Sponziello M. Update on Fundamental Mechanisms of Thyroid Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11(March):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00102.

Plaza-Menacho I. Structure and function of RET in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(2):T79–90. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-17-0354.

Mulligan LM. 65 YEARS OF THE DOUBLE HELIX: Exploiting insights on the RET receptor for personalized cancer medicine. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(8):T189–200. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-18-0141.

Nikiforov YE, Rowland JM, Bove KE, Monforte-Munoz H, Fagin JA. Distinct pattern of ret oncogene rearrangements in morphological variants of radiation-induced and sporadic thyroid papillary carcinomas in children. Cancer Res. 1997;57(9):1690–4.

Santoro M, et al. Gene rearrangement and Chernobyl related thyroid cancers. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(2):315–22. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.1999.0921.

Staubitz JI, et al. ANKRD26-RET - A novel gene fusion involving RET in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2019;238:10–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergen.2019.07.002.

Zou M, Shi Y, Farid NR. Low rate of ret proto-oncogene activation (PTC/retTPC) in papillary thyroid carcinomas from Saudi Arabia. Cancer. 1994;73(1):176–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19940101)73:1<176::aid-cncr2820730130>3.0.co;2-t.

Vuong HG, et al. The changing characteristics and molecular profiles of papillary thyroid carcinoma over time: A systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017;8(6):10637–49. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12885.

Santoro M, Moccia M, Federico G, Carlomagno F. “RET Gene Fusions in Malignancies of the Thyroid and Other Tissues.,” Genes (Basel). 2020;11(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11040424.

Paulson VA, Rudzinski ER, Hawkins DS. Thyroid cancer in the pediatric population. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10090723.

Su, et al. RET/PTC Rearrangements Are Associated with Elevated Postoperative TSH Levels and Multifocal Lesions in Papillary Thyroid Cancer without Concomitant Thyroid Benign Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165596.

Treglia G, Rufini V, Salvatori M, Giordano A, Giovanella L. PET Imaging in Recurrent Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Int J Mol Imaging. 2012;2012: 324686. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/324686.

Treglia G, Rufini V, Piccardo A, Imperiale A. Update on Management of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Focus on Nuclear Medicine. Semin Nucl Med. 2023;53(4):481–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2023.01.003.

Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00766.

Wan PTC, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116(6):855–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00215-6.

Kim KH, Kang DW, Kim SH, Seong IO, Kang DY. Mutations of the BRAF gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma in a Korean population. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45(5):818–21. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2004.45.5.818.

Adeniran AJ, et al. Correlation between genetic alterations and microscopic features, clinical manifestations, and prognostic characteristics of thyroid papillary carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(2):216–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000176432.73455.1b.

Kimura ET, Nikiforova MN, Zhu Z, Knauf JA, Nikiforov YE, Fagin JA. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1454–7.

Trovisco V, et al. BRAF mutations are associated with some histological types of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Pathol. 2004;202(2):247–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1511.

Li X, Kwon H. The impact of braf mutation on the recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(8):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082056.

Liu C, Chen T, Liu Z. Associations between BRAF(V600E) and prognostic factors and poor outcomes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0979-1.

Zhang Q, Liu SZ, Guan YX, Chen QJ, Zhu QY. Meta-analyses of association between BRAF V600E mutation and clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(2):763–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443032.

Jung C-K, et al. Mutational patterns and novel mutations of the BRAF gene in a large cohort of Korean patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2012;22(8):791–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2011.0123.

Xie H, Wei B, Shen H, Gao Y, Wang L, Liu H. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and its association with clinicopathological features and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI). Am J Transl Res. 2018;10(8):2726–36.

Xing M, et al. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2718–26. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5094.

Elisei R, et al. The BRAF(V600E) mutation is an independent, poor prognostic factor for the outcome of patients with low-risk intrathyroid papillary thyroid carcinoma: single-institution results from a large cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4390–8. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1775.

Lee SH, et al. Association Between (18)F-FDG Avidity and the BRAF Mutation in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2010). 2016;50(1):38–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13139-015-0367-8.

Nagarajah J, Ho AL, Tuttle RM, Weber WA, Grewal RK. Correlation of BRAFV600E Mutation and Glucose Metabolism in Thyroid Cancer Patients: An 18F-FDG PET Study. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(5):662–7. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.114.150607.

Xi X, Han J, Zhang JZ. Stimulation of glucose transport by AMP-activated protein kinase via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(44):41029–34. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M102824200.

Song H, et al. HIF-1α/YAP Signaling Rewrites Glucose/Iodine Metabolism Program to Promote Papillary Thyroid Cancer Progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(1):225–41. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.75459.

Yoshikawa T, et al. Association of (18)F- fluorodeoxyglucose uptake with the expression of metabolism-related molecules in papillary thyroid cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2024;51(4):696–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2024.04.008.

Haugen BR, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2015.0020.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCCN Guidelines, version 4.2023 Thyroid Carcinoma. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2024.

Wirth LJ, et al. Efficacy of Selpercatinib in RET-Altered Thyroid Cancers. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):825–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2005651.

Busaidy NL, et al. Dabrafenib Versus Dabrafenib + Trametinib in BRAF-Mutated Radioactive Iodine Refractory Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Results of a Randomized, Phase 2, Open-Label Multicenter Trial. Thyroid. 2022;32(10):1184–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2022.0115.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Dr. Seiji Yano for providing the RET rearrangements positive PTC cell line and Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

Research funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KE and TY made significant contributions to the design of this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Investigational Review Board of Kanazawa University (approval no. 202596). The consent to participate in the research was obtained through opt-out.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uno, D., Endo, K., Yoshikawa, T. et al. Correlation between gene mutations and clinical characteristics in papillary thyroid cancer: a retrospective analysis of BRAF mutations and RET rearrangements. Thyroid Res 17, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13044-024-00209-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13044-024-00209-4