Abstract

Background

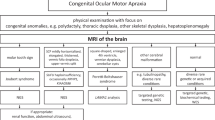

The nosological assignment of congenital ocular motor apraxia type Cogan (COMA) is still controversial. While regarded as a distinct entity by some authorities including the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man catalog of genetic disorders, others consider COMA merely a clinical symptom.

Methods

We performed a retrospective multicenter data collection study with re-evaluation of clinical and neuroimaging data of 21 previously unreported patients (8 female, 13 male, ages ranging from 2 to 24 years) diagnosed as having COMA.

Results

Ocular motor apraxia (OMA) was recognized during the first year of life and confined to horizontal pursuit in all patients. OMA attenuated over the years in most cases, regressed completely in two siblings, and persisted unimproved in one individual. Accompanying clinical features included early onset ataxia in most patients and cognitive impairment with learning disability (n = 6) or intellectual disability (n = 4). Re-evaluation of MRI data sets revealed a hitherto unrecognized molar tooth sign diagnostic for Joubert syndrome in 11 patients, neuroimaging features of Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome in one case and cerebral malformation suspicious of a tubulinopathy in another subject. In the remainder, MRI showed vermian hypo-/dysplasia in 4 and no abnormalities in another 4 patients. There was a strong trend to more severe cognitive impairment in patients with Joubert syndrome compared to those with inconclusive MRI, but otherwise no significant difference in clinical phenotypes between these two groups.

Conclusions

Systematical renewed analysis of neuroimaging data resulted in a diagnostic reappraisal in the majority of patients with early-onset OMA in the cohort reported here. This finding poses a further challenge to the notion of COMA constituting a separate entity and underlines the need for an expert assessment of neuroimaging in children with COMA, especially if they show cognitive impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The term congenital ocular motor apraxia (COMA) was introduced by Cogan in 1952 when he described a particular disorder of voluntary horizontal gaze in four children [1]. “Inability to turn the eyes voluntarily in a direction for which there is full involuntary … control” together with compensatory, jerky head movements constituted the clinical hallmark of this condition. COMA is related to the inability to initiate saccades.

During subsequent decades a wide range of disorders associated with ocular motor apraxia (OMA) was recognized [2]. However, several reviews and case reports of congenital OMA, alternatively called “infantile-onset saccade initiation delay”, stressed frequent consistent co-occurrence with early-onset cerebellar ataxia and global developmental delay [3–9]. Typically, OMA and ataxia resolve over the years, while cognitive impairment persists to variable degree [4, 7–9]. Thus, while OMA constitutes a symptom, not a diagnosis [2], a concept of COMA emerged indicating that this condition frames a clinical entity and a genetic disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. The Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) catalog of human genes and genetic disorders provides a separate coding number (%257550) for COMA. However, no gene associated with isolated COMA has been identified yet.

On the other hand, early-onset OMA is a frequent symptom of Joubert syndrome (JBTS), accompanied by infantile muscular hypotonia, early-onset ataxia, neonatal breathing abnormalities with episodic tachypnea and apnea, as well as developmental delay/intellectual disability [10–12]. Thus there is considerable phenotypic overlap of COMA and JBTS. Yet, both conditions are separated on the basis of neuroimaging characteristics.

MRI in COMA was reported to be either normal or show a vermian hypoplasia, preferentially of the inferior portion of the vermis [13, 14]. A recent review of studies performed between 1952 and 2012 included 91 patients with a clinical phenotype consistent with COMA and found MRI to be allegedly normal in 55 of them [15].

In contrast, a highly characteristic neuroimaging feature of JBTS in axial MRI of the brainstem was recognized in 1997 and designated the “molar tooth sign” (MTS) [16]. The “molar tooth” derives from the combination of elongated, thickened and horizontalised superior cerebellar peduncles; hypo-/dysplasia of the cerebellar vermis; and an abnormally deep interpeduncular fossa at the section of the brainstem isthmus and upper pons [12]. It is now considered to be pathognomonic for JBTS [17].

Our study presented here originally aimed at identification of the gene associated with COMA. However, re-evaluation of clinical and neuroimaging data of patients recruited with the diagnosis of COMA indicated that delineation of COMA versus JBTS and clarification of the nosological relationship between these two conditions are mandatory and a prerequisite for genetic investigations in COMA.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Göttingen (file no. 19/5/14). Written informed consent was obtained from all families.

Patient cohort

Patients diagnosed as having COMA were collected (i) from the cohort of patients of the Department of Pediatric Neurology, University Medical Center Göttingen (n = 4) and (ii) using an email based acquisition of rare neurological disorders in childhood (“Erhebung Seltener Neurologischer Erkrankungen im Kindesalter, ESNEK”) [18] from pediatric neurologists in Germany (n = 16) and Switzerland (n = 1).

Inclusion criteria for the definite COMA cohort comprised written informed consent of the parents or the patient or both, early-onset OMA (diagnostic recognition within the first year of life), and availability of an MRI in technical quality adequate for assessment of especially brainstem and cerebellum. We did not include patients with the MTS already recognized on MRI, thus with a preexisting diagnosis of JBTS.

Clinical and qualitative neuroimaging analysis

Demographic data, neurological features and information about the developmental stage were compiled by review of the clinical histories and by clinical-neurological follow-up investigations. Information about ophthalmological features was collected from neuro-ophthalmological or pediatric-neurological reports. Cognitive function was assessed using standardized neuropsychological tests whenever possible. Otherwise, the stage of mental developmental was appraised from the patient’s history, clinical examination, and reports from nursery or school. Additional data were collected in an interview with the parents conducted by telephone using a standardized questionnaire (Additional file 1).

A comparison concerning qualitative neurological features and quantifiable developmental data of the patient subgroups with MTS on MRI vs. inconclusive MRI was performed using T-test for independent variables and Fisher´s exact test.

All MRI data sets were analyzed independently by two pediatric neurologists with experience in neuroimaging of the brainstem and cerebellum (EB, KB) [19]. All available imaging sequences in axial, coronal and sagittal orientation were scrutinized with focus on size and position of the superior cerebellar peduncles, hypo-/dysplasia of the cerebellar vermis, cerebellar cysts, brainstem morphology including shape of the interpeduncular fossa at the section of the brainstem isthmus and upper pons, size and shape of the 4th ventricle, and any other cerebellar or cerebral malformations.

Results

A total of 28 patients were recruited via email based acquisition and from our own department. Among these, critical reappraisal of disease course and clinical features revealed that phenotypes were not consistent with COMA in three cases (e.g., onset of OMA later than 2nd birthday, neuroophthalmological features not consistent with OMA). In additional three patients cranial MRI was not available in sufficient technical quality. One patient already had a molecular genetic diagnosis of JBTS. Thus 21 patients were included in this study (13 male, 8 female, two pairs of siblings, mean age 10 years 3 months, age range 2 years 8 months - 24 years). Parental consanguinity was reported in one patient (#7). Table 1 summarizes clinical and neuroimaging features of all 21 patients. The period during which COMA was diagnosed in these patients spans from 1992 to 2013.

Ophthalmological features

In all patients OMA was recognized by attending physicians during the child´s first year of life. Most children (15 of 21 cases) presented with visual problems already in the first months of life, before OMA was definitely diagnosed, occasionally giving rise to the concern of severe visual impairment or even blindness. Initial visual symptoms included lack of fixation and visual pursuit (n = 12), nystagmus (n = 5), head tilting (n = 3), and strabism (n = 2), with ages at onset ranging from 4 weeks to 6 months.

Inability to perform normal voluntary saccades was confined to horizontal pursuit, vertical OMA was not observed in any of our patients. In almost all subjects OMA gradually ameliorated over the years, with complete cessation in two siblings (#8 and #9) at age 4 and 5 years. Additional oculomotor features comprised nystagmus in three patients and Duane syndrome in two siblings (#8 and #9).

Neurological features and developmental course

In most patients, early-onset cerebellar ataxia together with muscular hypotonia constituted further clinical hallmarks with gradual amelioration during the first decade, while general clumsiness persisted. Motor development was delayed in most cases, unsupported walking was achieved at ages ranging from 14 months to four years (mean 25 months). All subjects showed gradual ongoing improvement of motor skills. Development of both, language perception and expressive speech was delayed as well in all but two cases. An impairment of cognitive development was observed in 11 cases comprising learning disability (IQ 70-84; n = 7) or intellectual disability (IQ <70; n = 4).

Neuroimaging features

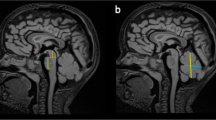

Systematic analysis of all MRI data sets revealed a MTS in 11 patients, indicating JBTS (Fig. 1). Among these patients with MTS, 10 additionally had vermian hypo-/dysplasia, predominantly of the superior part of the vermis cerebelli, and one of these cases showed agenesis of the corpus callosum. In one patient with MTS, MRI was otherwise normal. In one male patient (#7) cerebellar dysplasia, cerebellar cysts, and enlargement as well as square shape of the 4th ventricle clearly pointed to Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome [20, 21]. One patient had dysmorphic basal ganglia, abnormal shape of frontal horns, abnormal corpus callosum, reduced pontine prominence, and enlarged ventricles, suspicious of a tubulinopathy [22]. In 4 cases MRI revealed vermian hypo-/dysplasia as sole abnormality. MRI was normal in the remaining 4 patients (Fig. 2).

Molar tooth sign on MRI of an infant with Joubert syndrome. a, b Sagittal T1-weighted and c-d axial T2-weighted MRI of patient #1 at age 8 months. a Midsagittal slice shows vermian hypo-/dysplasia (arrows), rostral shifting of the fastigium (star), and deep interpeduncular fossa (arrowhead). b Parasagittal slice displays thickened and horizontalized superior cerebellar peduncles (SCP)(arrow). c-e Axial slices show deep interpeduncular fossa (arrowhead) and elongated SCP (arrows), resulting in “molar tooth sign”, and irregular folia of upper vermis (circle). These MRI features indicate Joubert syndrome

Normal MRI in a 19-year-old patient with COMA. a, b Sagittal and (c) axial T2-weighted MRI of patient #18 at age 19 years. a Midsagittal slice shows normal position of fastigium (star) and well developed vermis. b Parasagittal slice displays thin superior cerebellar peduncles (SCP) in oblique position (arrow). c Axial slice shows normal SCP (arrow). This MRI is normal

Comparison of clinical phenotypes of COMA vs. JBTS

A comparison of qualitative clinical features and quantitative developmental data revealed no difference between the subgroup of patients with inconclusive MRI vs. those with MTS on MRI concerning present age, age at diagnosis of COMA, and amelioration of OMA (Table 2). Unsupported walking was attained at slightly higher ages in children with JBTS, and there was a strong trend to more severe cognitive impairment in JBTS. However, these differences did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to small case numbers.

Various features

A 17-year-old boy with MTS (# 4) had retinal coloboma, neonatal breathing dysregulation, and persistently elevated liver enzymes. These features are well-known in JBTS with liver involvement due to TMEM67 mutations [23], but had not been recognized earlier as pointing to JBTS in our patient. Patient # 15 with MTS had congenital clubfoot, which was occasionally reported in JBTS, namely in a 4-year-old girl with a homozygous frameshift mutation in the RPGRIP1L gene [24]. No other clinical or laboratory features of JBTS, including polydactyly, facial dysmorphism, neonatal breathing dysregulation, skeletal dysplasia, cystic dysplastic kidneys, liver fibrosis, midline oral or facial defects, and oral soft tumors were observed in any of the remaining 9 patients with MTS.

Discussion

In our cohort of 21 patients with clinical phenotypes consistent with COMA a reappraisal of MR images primarily judged to be normal revealed a MTS in 11 patients. Thus the majority of patients clinically diagnosed to have COMA can in fact be assigned to JBTS. All these MR images had previously been analyzed by board-certified radiologists or neuroradiologists, in some cases with explicit question whether there is a MTS, and had been rated as normal.

Several factors contribute to the difficulties in recognition of the MTS in our cohort: The molar tooth is a characteristic, but subtle MRI sign which is easily missed. It was recognized as a typical hallmark of JBTS in neuroimaging only in 1997, 28 years after first description of JBTS as a clinical syndrome [16]. MRI was introduced in clinical neurology in the mid-1980s. According to a medline search seven articles dealing with JBTS and MRI were published in scientific journals from 1989 until 1997 without perceiving the MTS. In two siblings (#8 and #9) of our cohort the first MRI was performed before 1997. Finally, technical shortcomings of the MRI investigation including inadequate angulation or slice thickness may additionally hamper recognition of the MTS.

In two additional patients of our cohort re-evaluation of MRI revealed otherwise specific neuroimaging features. An 18-year-old man (#7) with clinical phenotype consistent with COMA had clear MRI characteristics of Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome, and a 10-year-old boy showed neuroimaging features pointing to a tubulinopathy. Appropriate molecular genetic investigations are under way in these two cases. In the remaining 8 patients with clinical phenotype consistent with COMA MRI revealed no conclusive findings.

These results strongly underline that a brain MRI of a child with COMA needs to be reviewed by a neuroradiologist or neurologist with experience in pediatric posterior fossa diseases, particularly malformations. As has been shown for brain MRI in children with cerebral palsy the accuracy of neuroimaging reports clearly depends on the expertise of those reporting [25]. An expert review is even more important in a child with COMA and abnormal cognitive function, as the chance of a MTS is much higher in this subgroup of children with COMA (73 % vs. 25 % in our cohort).

Among the four patients originally described by Cogan in 1952, no other neurologic symptoms were present in two, while one had convulsions shortly after birth without neurologic sequelae and one had a persistent extrapyramidal disorder assigned to intrauterine carbon monoxide poisoning [1]. The follow-up report of these 4 patients 14 years later stated difficulties in reading (due to OMA) and normal intelligence in three patients, with additional mild balance problems in one of them. The patient with carbon monoxide poisoning had spasticity, ataxia and borderline intellectual disability [26]. It is obvious from these clinical depictions that in his original report Cogan did not delineate a homogeneous clinical entity but rather described a clinical sign observed in a small heterogeneous group of patients. Once OMA was recognized by neurologists and ophthalmologists the relatively frequent co-occurrence of infantile-onset OMA (COMA) in sporadic and familial cases with early-onset ataxia and delay of psychomotor development resulted in the perception of COMA as an entity, namely a complex neurodevelopmental disorder with autosomal-recessive inheritance.

It has been doubted “whether Cogan-type oculomotor apraxia can exist as an isolated entity” [27], and a current concept assigns COMA to three main clinical conditions [28]: “a. In the “benign” or “idiopathic” variety of congenital ocular motor apraxia, neuroimaging is normal and there is no readily identifiable explanation for the disorder. Although the neurologic examination and intellect are usually normal, occasionally associated neurologic defects include hypotonia, motor and speech delay, and ataxia…b. Some patients with congenital ocular motor apraxia have a nonprogressive, noninherited structural abnormality of the brain, caused either by a developmental anomaly or by prenatal or perinatal insult. These include: dysgenesis of the cerebellar vermis or corpus callosum, inferior vermian hypoplasia, Dandy–Walker malformation, gray matter heterotopias, and perinatal ischemia. c. A variety of genetic disorders with multisystem involvement may present in infancy with congenital ocular motor apraxia. These include Joubert syndrome, Jeune syndrome (nephronophthisis, asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, retinal degeneration, and ataxia), and a subset of patients with Leber congenital amaurosis, a retinal dystrophy.” [28] Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome and tubulinopathies are to be added to this list of genetic disorders. JBTS, Jeune syndrome, and Leber congenital amaurosis are all ciliopathies and most likely overlapping phenotypes of the same group of diseases.

In contrast to this spectrum of conditions related to COMA, acquired OMA especially occurs in a range of different genetic disorders comprising ataxia teleangiectasia (AT), ataxia with ocular motor apraxia 1 (AOA1), and ataxia with ocular motor apraxia 2 (AOA2). The associated genes ATM (AT), aprataxin (AOA1) and senataxin (AOA2) are involved in mechanisms of DNA repair.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that a large subgroup of patients diagnosed with “benign” or “idiopathic” COMA in fact have JBTS, as the MTS was missed on MRI – which may easily happen. Therefore meticulous analysis of the MRI in patients with COMA is advisable. Furthermore we found no consistent differences in clinical phenotypes (developmental delay, intellectual impairment, ataxia) between patients with the MTS and those with “benign” or “idiopathic” COMA, apart from one case with Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome and one patient with clinical features pointing to JBTS which were however not previously recognized in their diagnostic value in these patients.

In the future, delineation of new clinical and genetic entities associated with early-onset OMA will possibly allow for assignment of hitherto ill-defined cases of “idiopathic” COMA to a specific diagnosis. Additional genetic studies using whole exome sequencing are needed to clarify whether a subset of cases with early-onset OMA without the MTS on MRI frames a nosological entity with a distinct genetic basis and autosomal recessive inheritance, possibly constituting a further part of the clinical and genetic spectrum of ciliopathies.

Abbreviations

AOA1, ataxia with ocular motor apraxia 1; AOA2, ataxia with ocular motor apraxia 2; AT, ataxia teleangiectasia (AT); COMA, congenital ocular motor apraxia; JBTS, Joubert syndrome; MTS, molar tooth sign; OMA, ocular motor apraxia

References

Cogan DG. A type of congenital ocular motor apraxia presenting jerky head movements. Trans Am Acad Ophthal Otolaryng. 1952;56:853–62.

Harris CM, Shawkat F, Russell-Eggitt I, Wilson J, Taylor D. Intermittent horizontal saccade failure ('ocular motor apraxia') in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:151–8.

Zee DS, Yee RD, Singer HS. Congenital ocular motor apraxia. Brain. 1977;100:581–99.

Rappaport L, Urion D, Strand K, Fulton AB. Concurrence of congenital ocular motor apraxia and other motor problems: an expanded syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29:85–90.

Steinlin M, Thun-Hohenstein L, Boltshauser E. Congenital oculomotor apraxia. Presentation--developmental problems--differential diagnosis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1992;200:623–5.

Jan JE, Kearney S, Groenveld M, Sargent MA, Poskitt KJ. Speech, cognition, and imaging studies in congenital ocular motor apraxia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:95–9.

Marr JE, Green SH, Willshaw HE. Neurodevelopmental implications of ocular motor apraxia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:815–9.

Kondo A, Saito Y, Floricel F, Maegaki Y, Ohno K. Congenital ocular motor apraxia: clinical and neuroradiological findings, and long-term intellectual prognosis. Brain Dev. 2007;29:431–8.

Salman MS, Ikeda KM. The syndrome of infantile-onset saccade initiation delay. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(2):235–40.

Joubert M, Eisenring JJ, Robb JP, Andermann F. Familial agenesis of the cerebellar vermis. A syndrome of episodic hyperpnea, abnormal eye movements, ataxia, and retardation. Neurology. 1969;19:813–25.

Maria BL, Boltshauser E, Palmer SC, Tran TX. Clinical features and revised diagnostic criteria in Joubert syndrome. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:583–90.

Romani M, Micalizzi A, Valente EM. Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:894–905.

Whitsel EA, Castillo M, D'Cruz O. Cerebellar vermis and midbrain dysgenesis in oculomotor apraxia: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:831–4.

Sargent MA, Poskitt KJ, Jan JE. Congenital ocular motor apraxia: imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1915–22.

Salman MS, Ikeda KM. Do the clinical features in infantile-onset saccade initiation delay (congenital ocular motor apraxia) correlate with brain magnetic resonance imaging findings? J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:246–50.

Maria BL, Hoang KB, Tusa RJ, et al. "Joubert syndrome" revisited: key ocular motor signs with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:423–30.

Poretti A, Boltshauser E, Valente EM. The molar tooth sign is pathognomonic for Joubert syndrome! Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50:e15–16.

Brockmann K. Erhebung Seltener Neurologischer Erkrankungen im Kindesalter. Neuropediatrics. 2014;45:fp036. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1390541.

Poretti A, Huisman TA, Scheer I, Boltshauser E. Joubert syndrome and related disorders: spectrum of neuroimaging findings in 75 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1459–63.

Poretti A, Häusler M, von Moers A, et al. Ataxia, intellectual disability, and ocular apraxia with cerebellar cysts: a new disease? Cerebellum. 2014;13:79–88.

Micalizzi A, Poretti A, Romani M, et al. Clinical, neuroradiological and molecular characterization of cerebellar dysplasia with cysts (Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome). Eur J Hum Genet. 2016 Mar 2. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.19. [Epub ahead of print]

Bahi-Buisson N, Poirier K, Fourniol F, et al. The wide spectrum of tubulinopathies: what are the key features for the diagnosis? Brain. 2014;137:1676–700.

Brancati F, Iannicelli M, Travaglini L, et al. MKS3/TMEM67 mutations are a major cause of COACH Syndrome, a Joubert Syndrome related disorder with liver involvement. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E432–442.

Brancati F, Travaglini L, Zablocka D, et al. RPGRIP1L mutations are mainly associated with the cerebello-renal phenotype of Joubert syndrome-related disorders. Clin Genet. 2008;74:164–70.

Horridge KA, Johnston J, Phatak V, Guadagno A. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in children and young people with cerebral palsy: who reports matters? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:375–7.

Cogan DG. Congenital ocular motor apraxia. Can J Ophthalmol. 1966;1:253–60.

Sattar S, Gleeson JG. The ciliopathies in neuronal development: a clinical approach to investigation of Joubert syndrome and Joubert syndrome-related disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:793–8.

Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL. Neuro-Ophthalmology. Diagnosis and management. 2nd edition, Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. pp. 560–562.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their families for participating in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Niedersächsische Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur (74ZN1284).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

SW and KB conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, participated in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. JB, H-MB, FvD, WD, MH, SH, SK, GK, CK, WM, DM, IS-A, JS, and SPT participated in acquisition of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SS, ML, and EB participated in coordination of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

No additional information.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As stated in the Methods section, this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Göttingen (file no. 19/5/14). Written informed consent was obtained from all families.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Congenital Ocular Motor Apraxia (COMA) – Questionnaire. (DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wente, S., Schröder, S., Buckard, J. et al. Nosological delineation of congenital ocular motor apraxia type Cogan: an observational study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 11, 104 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0486-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0486-z