Abstract

Background

Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) of the pancreas are extremely rare. Their pathogenesis and molecular landscape are largely unknown. Here, we report a case of mixed pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (NET) and identify its genetic alterations by next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Case presentation

A fifty-year-old male was admitted into the hospital for evaluation of a pancreatic lesion detected during a routine examination. Abdominal ultrasound indicated a hypoechoic mass of 2.6 cm at the head of the pancreas. Malignancy was suspected and partial pancreatectomy was performed. Thorough histopathological examination revealed a mixed IPMN-NET. In some areas, the two components were relatively separated, whereas in other areas IPMN and NET grew in a composite pattern: The papillae were lined with epithelial cells of IPMN, and there were clusters of NET nests in the stroma of papillary axis. NGS revealed shared somatic mutations (KRAS, PCK1, MLL3) in both components. The patient has been uneventful 21 months after the surgery.

Conclusions

Our case provides evidence of a common origin for mixed IPMN-NET with composite growth features. Our result and literature review indicate that KRAS mutation might be a driver event underlying the occurrence of MiNEN. We also recommend the inclusion of mixed non-invasive exocrine neoplasms and neuroendocrine neoplasms into MiNEN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) of the pancreas are a heterogenous group of malignancies and are extremely rare. According to the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of endocrine organs and the 2019 WHO classification of digestive system tumors, MiNENs are carcinomas composed of both a non-neuroendocrine carcinoma and neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN), each of which constitutes ≥30% of the neoplasm [1,2,3,4]. Most pancreatic MiNENs are mixed ductal-neuroendocrine carcinomas or mixed acinar-neuroendocrine carcinomas and both components are usually high-grade [5]. Although the current WHO definition requires that the non-neuroendocrine counterparts be invasive carcinoma, occasionally they can be solely carcinoma precursors [6]. Here, we present an extremely unusual case of mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (NET) with detailed discussion about its growth pattern.

The etiology of MiNEN is controversial and largely unknown. The current WHO category applies only to tumors in which two components are clonally related, but not to two collision tumors [4]. To understand the relationship between the two components and to explore the pathogenesis, we manage to separate them by macrodissection and perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) with a panel of 1021 genes. The presentation of this case and literature review would help elucidate the possible origin of mixed IPMN-NET.

Case presentation

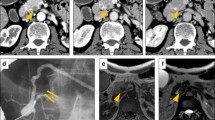

A fifty-year-old male was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of a pancreatic lesion detected during a routine examination. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic mass of 2.6 cm at the head of the pancreas (Fig. 1A). The mass infiltrated into the surrounding adipose tissue and a pancreatic carcinoma could not be ruled out. The patient was asymptomatic and the serum tumor markers including CA-125, CA19–9, CA72–4, CEA, and AFP were all within normal limits. The patient had no medical or psycho-social history and no genetic tests were performed previously. Physical examination revealed no obvious abnormalities. Ultrasound-guided pancreatic fine needle aspiration was performed. On the cell block, the lesion was composed of mucinous columnar cells with mild dysplasia and scattered plasmacytoid cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed AE1/AE3(+), chromogranin A (CgA) (+), synaptophysin (Syn) (+), and β-catenin (membranous +). Therefore, a mixed mucinous neoplasm and NEN was suspected.

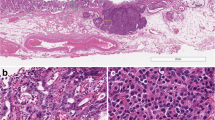

Partial pancreatectomy was performed. Grossly, the specimen measured 5.3 × 4.0 × 3.3 cm. On the cut surface, a cystic lesion with rough inner surface was found. The cyst measured 1.5 cm (Fig. 2). Careful histological examination revealed two components: IPMN and neuroendocrine components (Fig. 3). In some areas of the cyst, there was a classical IPMN component characterized by papillae forming and intraductal proliferation of columnar mucin-producing cells. Neuroendocrine components measured about 1.2 cm and could be found along the wall of the cyst, within the pancreatic tissue, as well as inside of the stroma of papillae. It grew in an organoid or trabecular pattern and partially infiltrated into the surrounding tissue, consistent with the imaging features. The nuclei were round to oval, with fine (salt-and-pepper) chromatin. The cytoplasm was finely granular and slightly eosinophilic. Positive staining for CgA and Syn confirmed the neuroendocrine differentiation (Fig. 4A, B). IHC for various hormones were also performed and the neuroendocrine components showed positive for glucagon and negative for gastrin, insulin, and somatostatin (Fig. 4C-E). The background pancreatic tissue was nearly normal: The structure of lobules was clear. Little acute or chronic inflammation, fibrosis, or acinar atrophy was observed (Fig. 3F). There was no other IPMN, mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), or pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN). The number, shape and size of islets were normal.

A Mixed areas of IPMN (left) and NET (right) components (HEx40). (B) Relative separate NET component (HEx40). (C) Relative separate IPMN component was composed of papillae covered by epithelial cells with mild to moderate dysplasia (HEx100). (D) Relative separate NET component showed the NET cells had round to oval nuclei. Few mitoses were found (HEx100). (E) In mixed areas, the papillae were lined with epithelial cells of IPMN, and filled with clusters of NET nests in the stroma (HEx100). Inset: Composite IPMN-NET. (F) Pancreatic tissue in the background was relatively normal (HEx40)

(A) NET component was positive for CgA (IHCx100). (B) NET component was strongly positive for Syn (IHCx100). (C) NET component was positive for glucagon (IHCx100). (D) NET component was negative for insulin (IHCx100). (E) NET component was negative for somatostatin (IHCx100). (F) Composite IPMN-NET showed a low Ki-67 index (IHCx100)

For the neuroendocrine components, an NET rather than neuroendocrine hyperplasia (islet hyperplasia) was considered for several reasons: First, the lesion was relatively isolated and the background pancreatic tissue was normal. There was no increased number or size of islets and their shape was regular. The β-cells showed normal nuclei without enlarged or hyperchromatic characteristics. In contrast, neuroendocrine hyperplasia more commonly had multiple atypical β-cells, increased number and size of islets, irregular islet shape, and sometimes patients could have history of chronic pancreatitis, carcinoma, etc. Second, the diameter of the lesion (1.2 cm) was even larger than the cut-off value of pancreatic neuroendocrine microadenomas (0.5 cm). Third, the lesion was diffusely positive for only one hormone, whereas neuroendocrine hyperplasia was usually composed of several types of endocrine cells. In addition, clinically, the latter was more commonly related to hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia rather than α-cell hyperplasia with or without hyperglucagonemia.

Notably, in some areas of the cyst, the two components were highly intermingled and grew in a “truly mixed” pattern. The papillae were lined with epithelial cells of IPMN, and there were clusters of NET nests in the stroma (Fig. 3E). The whole lesion was composed of approximately 60% of IPMN component and 40% of NET. No lymph node metastasis, angioinvasion, or perineural spreading was found.

Each component was graded according to the 2019 WHO classification of digestive system tumors 4, 5. For IPMN, the architecture of papillae was simple and cell nuclei were mild to moderate atypia, mostly located at the base of the cells. Few mitoses were found. Thorough sampling of the lesion revealed no invasive carcinoma. Therefore, it was graded as IPMN with low-grade dysplasia. For NET, HE staining revealed mild nuclei atypia, no necrosis, and few mitoses (< 1/10HPFs). Ki-67 index by IHC was 2% (Fig. 4F). Therefore, the NET was graded as G1. Our final diagnosis was mixed IPMN-NET.

We further explored the molecular changes of this tumor. The two components were separated by macrodissection. Each component contained a minimum of 60% of tumor. DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Genomic DNA were sheared into 200-bp to 250-bp fragments using a Covaris S2 instrument (Woburn, MA, USA), and indexed NGS libraries were prepared. All libraries were hybridized to self-built probes and sequencing was performed using the MGISeq-2000 Sequencing System (BGI, Shenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines with a panel of 1021 cancer-related genes (Supplementary table). The average sequencing depth was 655x. Single nucleotide variants (SNV), insertions or deletions (INDEL), gene fusions, and copy number variations (CNV) were analyzed and several point mutations in KRAS, PCK1, MLL3 were identified (Table 1). The tumor mutation burden (TMB) in both components was low: 0.96Muts/Mb in IPMN component and 0.96Muts/Mb in NET component. No INDEL, gene fusions or CNV were detected. The mutation status of PCK1 and MLL3 in pacreatic neoplasms was searched in Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) database and provided in Table 2. No germline mutations were detected.

Currently, the patient is uneventful at 21 months of regular follow-up.

Discussion

We describe a mixed IPMN-NET pathologically characterized by both “truly mixed” pattern and relatively separated pattern. Although the clinicopathological features of concomitant IPMN and NEN have been described, researchers have not paid much attention to their growth pattern, which might have relationship with their pathogenesis. We summarize previously reported cases and classify them according to the morphological classification by de Mestier et al. (Table 3) [3]. Regrading of IPMN and NEN is based on the 2019 WHO classification of digestive system tumors and 2017 WHO classification of tumors of endocrine organs. Literature review of their pathological features demonstrates that most of them are concurrent or collision (Case 1–14 in Table 3), which should not be considered as MiNEN. A truly composite IPMN-NEN is extremely rare (Case 31–33 in Table 3). Notably, although Case 16 partially grew in a way which could not be classified clearly, further cytogenetic analysis confirmed their collision pattern [21].

Mixed non-endocrine and endocrine components in digestive system tumors have been described early [28,29,30,31]. It was considered that most cases contained at least adenocarcinoma and the 2010 WHO classification used “mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma” (MANEC) to describe them [32,33,34]. However, the previous term did not cover all the possibilities, and the 2019 WHO has replaced it with MiNEN [2, 4]. Notably, neoplasms whose non-neuroendocrine components are solely preinvasive lesions are still excluded [4]. Another term has been proposed to describe these subtypes: “Mixed adenoneuroendocrine tumor” (MANET) is used to underline an indolent group of tumors composed of adenoma and well-differentiated NET [35, 36]. Based on previous research, MANET is more commonly used and discussed in stomach, colon, and rectum [35, 37,38,39]. However, similar situations happen in pancreas and a mixed IPMN-NET also theoretically fulfills the requirements of mixed “adenoma” and well-differentiated NET. No mixed intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN)-NEN, mixed intraductal oncocytic neoplasm (IOPN)-NEN, or mixed MCN-NEN has been reported. Only rare cases of MCN with associated invasive carcinoma and neuroendocrine component have been reported [40].

The current definition of MiNEN also requires that the two tumor components be a single tumor of common origin rather than a collision of two tumors. The two components in our case are not only morphologically intermingled, but also have similar molecular changes. Our case and literature review demonstrate that the entity of two well-differentiated, clonally related components does exist, and the non-neuroendocrine components could be non-invasive [3]. Based on this fact and the miscellaneous terms that have been used (MiNEN, MANEC, MANET), we recommend that the subgroup of non-invasive exocrine neoplasms as non-neuroendocrine counterparts (including MANET) be included in MiNEN. We also recommend that the two components should be reported and graded separately in clinical practice, since different components could have different prognosis (Table 3) [41, 42]. In our case, the clinical behavior is relatively benign, which is consistent with other composite IPMN-NET and further supports the heterogeneity of outcome depending on the histological subtypes [6, 26, 27]. Another point that needs to be kept in mind is the differential diagnosis between NET and neuroendocrine hyperplasia. The latter has a series of major and minor critieria and its diagnosis, especially diffuse hyperplasia, might need near total pancreatectomy [43,44,45].

The pathogenesis of concomitant IPMN and NEN is controversial. Four hypotheses have been proposed. The first is collision of IPMN and NEN [14]. The second is transdifferentiation of IPMN cells into NEN cells. The third is transdifferentiation of NEN cells into IPMN cells [13, 27]. The fourth hypothesis is that pancreatic progenitor cells differentiate into both NEN and IPMN cells [27]. Based on histopathology, the hypothesis of transdifferentiation seemed unlikely when IPMN and NEN happened in different sites, which is the condition in most of the cases (Table 3). However, deeper investigation is lacking and not much research has demonstrated the genetic alterations of concomitant IPMN-NET. In 2013, Moriyoshi et al. firstly proved the hypothesis of collision by cytogenetic analysis of LOH in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 [21]. Tewari et al. performed molecular testing for KRAS in two cases of concomitant IPMN (invasion in one case) and NEC and both were wild-type [15]. Currently, only 2 cases of mixed IPMN-NET with typical composite morphology included molecular studies (Table 3) [6, 27]. Igarashi et al. first revealed the presence of KRAS (p.G12V) mutation in IPMN and transitional areas rather than NET area, supporting the fourth hypothesis [27]. Schiavo Lena et al. detected KRAS (p.G12D), GNAS (p.R201H), CDKN2A (p.Y44*) mutations and CCND1 amplification (copy number 28) in both IPMN and NET components, serving as an evidence of a common cell origin [6]. Based on the currently limited data, our study used broad panel NGS instead of focusing on a few genes and provided the molecular landscape of composite IPMN-NET. We also identified KRAS mutation in both components. Combining the results, KRAS mutation might be an important diver mutation of composite IPMN-NET. Since the status of KRAS have been studied in pure IPMN and NEN in multiple studies, we further searched COSMIC database for the information of the other two mutated genes (PCK1 and MLL3) in pancreatic neoplasms (Table 2) [46,47,48]. We found that most PCK1 mutations occur in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (several samples with unknown histology subtype). The specific PCK1 p.P605H (c.1814C > A) mutation has only been reported in squamous cell carcinoma in the lung (sample name: TCGA-70-6722-01). For MLL3, its mutation has been reported in various pancreatic lesions including NEN and simple mucinous cysts, but not in IPMN (Tables 1,2) [49]. Intertestingly, it has also been detected in neuroendocrine components in one gastric MiNEN [50]. However, MLL3 p.V649M (c.1945G > A) has never been reported. Our result suggests there might be other unknown mechanisms underlying composite IPMN-NET. A comparison between mixed IPMN-NET and its pure tumor counterparts is also shown in Table 1. According to Schiavo Lena et al., mixed IPMN-NET seems to share more genetic changes with IPMN [6]. However, our result favors the unique molecular alterations in composite IPMN-NET. Additionally, the same mutation spectrum in two components supports the hypothesis of one common origin.

Our study has limitations: Contaminations might happen during sampling and influence the results of gene mutation analysis. The relatively small size of the lesion might add to this problem. Besides, due to the rarity of pancreatic MiNEN, further molecular studies are required to explore the other subtypes of MiNEN and in morphologically “collision” neoplasms.

In conclusion, our case provides new insights into the morphological features and the genetic changes in a composite IPMN-NET. We also recommend a broader and clearer category of MiNEN in clinical work.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- CgA:

-

Chromogranin A

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin stain

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- INDEL:

-

Insertion or deletion

- IOPN:

-

Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- ITPN:

-

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm

- LOH:

-

Loss of heterozygosity

- MANEC:

-

Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma

- MANET:

-

Mixed adenoneuroendocrine tumor

- Mb:

-

Megabase

- MCN:

-

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

- MiNEN:

-

Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm

- MLL3 :

-

Mixed-lineage leukemia protein 3

- NEN:

-

Neuroendocrine neoplasm

- NET:

-

Neuroendocrine tumor

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PCK1 :

-

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- Syn:

-

Synaptophysin

- TMB:

-

Tumor mutation burden

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Guilmette JM, Nose V. Neoplasms of the neuroendocrine pancreas: an update in the classification, definition, and molecular genetic advances. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26(1):13–30.

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76(2):182–8.

de Mestier L, Cros J, Neuzillet C, Hentic O, Egal A, Muller N, et al. Digestive system mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(4):412–25.

WHO. Classification of Tumours editorial board, digestive system Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2019.

Frizziero M, Chakrabarty B, Nagy B, Lamarca A, Hubner RA, Valle JW, et al. Mixed Neuroendocrine Non-Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Systematic Review of a Controversial and Underestimated Diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1):273.

Schiavo Lena M, Cangi MG, Pecciarini L, Francaviglia I, Grassini G, Maire R, et al. Evidence of a common cell origin in a case of pancreatic mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-neuroendocrine tumor. Virchows Arch. 2021;478(6):1215–9.

Fujikura K, Hosoda W, Felsenstein M, Song Q, Reiter JG, Zheng L, et al. Multiregion whole-exome sequencing of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms reveals frequent somatic KLF4 mutations predominantly in low-grade regions. Gut. 2021;70(5):928–39.

Nagai K, Mizukami Y, Omori Y, Kin T, Yane K, Takahashi K, et al. Metachronous intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms disseminate via the pancreatic duct following resection. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(5):971–80.

Yan J, Yu S, Jia C, Li M, Chen J. Molecular subtyping in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: new insights into clinical, pathological unmet needs and challenges. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1874;2020(1):188367.

Hong X, Qiao S, Li F, Wang W, Jiang R, Wu H, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals distinct genetic bases for insulinomas and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: leading to a new classification system. Gut. 2020;69(5):877–87.

Arakelyan J, Zohrabyan D, Philip PA. Molecular profile of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs): opportunities for personalized therapies. Cancer. 2021;127(3):345–53.

Raj N, Shah R, Stadler Z, Mukherjee S, Chou J, Untch B, et al. Real-time genomic characterization of metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors has prognostic implications and identifies potential germline Actionability. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:PO.17.00267. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00267.

Marrache F, Cazals-Hatem D, Kianmanesh R, Palazzo L, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, et al. Endocrine tumor and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a fortuitous association? Pancreas. 2005;31(1):79–83.

Goh BK, Ooi LL, Kumarasinghe MP, Tan YM, Cheow PC, Chow PK, et al. Clinicopathological features of patients with concomitant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas and pancreatic endocrine neoplasm. Pancreatology. 2006;6(6):520–6.

Tewari N, Zaitoun AM, Lindsay D, Abbas A, Ilyas M, Lobo DN. Three cases of concomitant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour. JOP. 2013;14(4):423–7.

Ishida M, Shiomi H, Naka S, Tani T, Okabe H. Concomitant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(1):63–7.

Mortele KJ, Peters HE, Odze RD, Glickman JN, Jajoo K, Banks PA. An unusual mixed tumor of the pancreas: sonographic and MDCT features. JOP. 2009;10(2):204–8.

Kadota Y, Shinoda M, Tanabe M, Tsujikawa H, Ueno A, Masugi Y, et al. Concomitant pancreatic endocrine neoplasm and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:75.

Ishizu S, Setoyama T, Ueo T, Ueda Y, Kodama Y, Ida H, et al. Concomitant case of Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas and functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-producing tumor): first report. Pancreas. 2016;45(6):e24–5.

Stukavec J, Jirasek T, Mandys V, Denemark L, Havluj L, Sosna B, et al. Poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma and intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: description of an unusual case. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(12):879–84.

Moriyoshi K, Minamiguchi S, Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Fujimoto M, Kawaguchi M, Haga H. Collision of extensive exocrine and neuroendocrine neoplasms in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 revealed by cytogenetic analysis of loss of heterozygosity: a case report. Pathol Int. 2013;63(9):469–75.

Gill KRS, Scimeca D, Stauffer J, Krishna M, Raimondo M. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors among patients with Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: real association or just a coincidence? JOP. 2009;10(5):515–7.

Larghi A, Stobinski M, Galasso D, Lecca PG, Costamagna G. Concomitant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and pancreatic endocrine tumour: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41(10):759–61.

Sahora K, Crippa S, Zamboni G, Ferrone C, Warshaw AL, Lillemoe K, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas with concurrent pancreatic and periampullary neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(2):197–204.

Costa JM, Carvalho S, Soares JB. Synchronous intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: more than a coincidence? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109(9):663–35.

Hashimoto Y, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Ohge H, et al. Mixed ductal-endocrine carcinoma derived from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas identified by human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) expression. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97(5):469–75.

Igarashi T, Harimoto N, Nobusawa S, Yoshida Y, Yamanaka T, Hagiwara K, et al. Evaluation of KRAS mutation status in a patient with concomitant pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm and Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Pancreas. 2019;48(5):e34–5.

Eusebi V, Capella C, Bondi A, Sessa F, Vezzadini P, Mancini AM. Endocrine-paracrine cells in pancreatic exocrine carcinomas. Histopathology. 1981;5(6):599–613.

Nonomura A, Kono N, Mizukami Y, Nakanuma Y, Matsubara F. Duct-acinar-islet cell tumor of the pancreas. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1992;16(3):317–29.

Schron DS, Mendelsohn G. Pancreatic carcinoma with duct, endocrine, and acinar differentiation. A histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1984;54(9):1766–70.

Kashiwabara K, Nakajima T, Shinkai H, Fukuda T, Oono Y, Kurabayashi Y, et al. A case of malignant duct-islet cell tumor of the pancreas immunohistochemical and cytofluorometric study. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1991;41(8):636–41.

Terada T, Kawaguchi M, Furukawa K, Sekido Y, Osamura Y. Minute mixed ductal-endocrine carcinoma of the pancreas with predominant intraductal growth. Pathol Int. 2002;52(11):740–6.

Terada T, Matsunaga Y, Maeta H, Endo K, Horie S, Ohta T. Mixed ductal-endocrine carcinoma of the pancreas presenting as gastrinoma with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: an autopsy case with a 24-year survival period. Virchows Arch. 1999;435(6):606–11.

Uccella S, La Rosa S. Looking into digestive mixed neuroendocrine - nonneuroendocrine neoplasms: subtypes, prognosis, and predictive factors. Histopathology. 2020;77(5):700–17.

La Rosa S, Uccella S, Molinari F, Savio A, Mete O, Vanoli A, et al. Mixed adenoma well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (MANET) of the digestive system: an indolent subtype of mixed neuroendocrine-NonNeuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN). Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(11):1503–12.

Grillo F, Valle L, Sammito G, Scabini S, Albertelli M, Mastracci L. Rectal mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN): high grade evolution of a MANET? Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216(4):152869.

Zaplotnik M, Plut S, Zidar N, Strnisa L, Gavric A. A rare gastric polyp: MANET. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(6):1422–3.

Fu Z, Saade R, Koo BH, Jennings TA, Lee H. Incidence of composite intestinal adenoma-microcarcinoid in 158 surgically resected polyps and its association with squamous morule. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;42:69–74.

Gaspar R, Santos-Antunes J, Marques M, Liberal R, Melo D, Pereira P, et al. Mixed Adenoneuroendocrine tumor of the rectum in an ulcerative colitis patient. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2019;26(2):125–7.

Gurzu S, Bara T, Molnar C, Bara T Jr, Butiurca V, Beres H, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition induces aggressivity of mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with neuroendocrine component: an immunohistochemistry study. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(1):82–9.

de Mestier L, Cros J. Digestive system mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN). Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2019;80(3):172–3.

Niessen A, Schimmack S, Weber TF, Mayer P, Bergmann F, Hinz U, et al. Presentation and outcome of mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2021;21(1):224–35.

Orujov M, Lai KK, Forse CL. Concurrent adult-onset diffuse beta-cell nesidioblastosis and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27(8):912–8.

Anlauf M, Wieben D, Perren A, Sipos B, Komminoth P, Raffel A, et al. Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in 15 adults with diffuse nesidioblastosis: diagnostic criteria, incidence, and characterization of beta-cell changes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(4):524–33.

Clancy TE, Moore FD Jr, Zinner MJ. Post-gastric bypass hyperinsulinism with nesidioblastosis: subtotal or total pancreatectomy may be needed to prevent recurrent hypoglycemia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(8):1116–9.

Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. KRAS, GNAS, and RNF43 mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1172.

Yuan F, Shi M, Ji J, Shi H, Zhou C, Yu Y, et al. KRAS and DAXX/ATRX gene mutations are correlated with the clinicopathological features, advanced diseases, and poor prognosis in Chinese patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10(9):957–65.

Maharjan CK, Ear PH, Tran CG, Howe JR, Chandrasekharan C, Quelle DE. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cancers. 2021;13(20):5117.

Attiyeh M, Zhang L, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Allen P, Imam R, Basturk O, et al. Simple mucinous cysts of the pancreas have heterogeneous somatic mutations. Hum Pathol. 2020;101:1–9.

Ishida S, Akita M, Fujikura K, Komatsu M, Sawada R, Matsumoto H, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma and mixed neuroendocrinenon-neuroendocrine neoplasm of the stomach: a clinicopathological and exome sequencing study. Hum Pathol. 2021;110:1–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WZ diagnosed the case. JC, PW, KL and WZ performed acquisition of the data. JC and PW performed the NGS sequencing and analyzed the results. JC and WZ wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to paticipate

The institutional review board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Wang, P., Lv, K. et al. Case report: composite pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and neuroendocrine tumor: a new mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm?. Diagn Pathol 16, 108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01165-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01165-5