Abstract

Background

Current literature systematically reports that interventions to attract and retain health workers in underserved areas need to be context specific but rarely defines what that means. In this systematic review, we try to summarize and analyse context factors influencing the implementation of interventions to attract and retain rural health workers.

Methods

We searched online databases, relevant websites and reference lists of selected literature to identify studies on compulsory rural service programmes and financial incentives. Forty studies were selected. Information regarding context factors at macro, meso and micro levels was extracted and synthesized.

Results

Macro-level context factors include political, economic and social factors. Meso-level factors include health system factors such as maldistribution of health workers, growing private sector, decentralization and health financing. Micro-level factors refer to the policy implementation process including funding sources, administrative agency, legislation process, monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusions

Macro-, meso- and micro-level context factors can play different roles in agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation of health interventions to attract and retain rural health workers. These factors should be systematically considered in the different stages of policy process and evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a worldwide issue that remote and rural areas tend to have far less human resources for health (HRH) than their population needs [1]. Universal health coverage will be impossible to achieve if there remain populations with insufficient access to qualified health workers [2]. Many countries have designed and implemented interventions to attract and retain health workers in remote and rural areas [3]. Most of the interventions are from high-income countries, such as the Medical Rural Bonded Scholarship (MRBS) Scheme as an Australian Government recent initiative designed to address the doctor shortage outside metropolitan areas across Australia [4]. A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) summarized and categorized these interventions into four broad categories: education, regulations, financial incentives and personal and professional support [5]. However, currently available evidence is contradictory and draws a complex picture on the intervention effectiveness. For example, one systematic review on financial incentives in underserved areas identified nine studies with increased uptake of rural jobs, two with negative findings and two with no significant differences [6].

These interventions were developed and implemented in various contexts and with different processes, which might help explain the variations of intervention effectiveness. The literature systematically reports that interventions to attract and retain health workers in underserved areas need to be context specific but rarely defines what that means [5,7]. A systematic review without consideration of these context factors may have limited value in providing guidance for countries to develop their own strategies.

Policy context includes all environmental factors under which a policy is made and implemented. Context factors in health policies can be classified in various ways according to the nature of the factors or the role they play in policymaking process. Leichter categorized context factors into situational factors, structural factors, cultural factors and environmental factors [8]. Collins discussed the context factors of health system reform in six dimensions: demographic and epidemiological change, processes of social and economic change, economic and financial policy, politics and the political regime, ideology, public policy and the public sector, and external factors [9]. Implementation process can also be considered as one important aspect of context [10]. While policy processes are usually divided into different stages including agenda setting, policy formulation and policy implementation, these context factors may have different influences on these policy stages.

Therefore, the objective of this review is to identify key context factors that policymakers should consider when they design and implement interventions. The context factors are discussed at three levels. Macro-level context factors include political, economic and social factors. Meso-level context factors include health system factors. Micro-level context factors refer to the implementation process of the intervention. This categorization will help analyse the potential roles that these context factors may play in the different stages of the policy process. We hope this analysis can help policymakers properly interpret the mixed evidence from existing literature and therefore help countries to design and implement context-specific intervention strategies to attract and retain rural health workers.

Methods

Search strategies

Data sources

Literature from three different sources was searched: online databases, relevant websites and reference lists of selected literature.

Online databases included PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ERIC, JSTOR, EconLit, SSRN, IDEAS, System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (OpenSIGLE), National Technical Information Service (NTIS), ProQuest Dissertation & Theses Database, ISI Proceedings and Popline.

Search terms

Four types of terms were applied in the literature search: 1) terms about study settings: remote, rural, primary health care, underdevelopment, under-served areas; 2) terms about participants: health personnel, health manpower, health professional, physicians, nurses; 3) terms about interventions: physician incentive plans, compulsory service, motivation, training; and 4) terms about effectiveness: personnel turnover, attraction, retention, recruitment.

Six websites were searched including the WHO website, The Global Health Workforce Alliance, World Bank, Capacity Project website, Asia Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health and Google Scholar (first 50 pages).

In the literature search process, no limitation was specified on the publication dates which meant literatures published in all time on this topic were eligible for the literature search.

Study selection

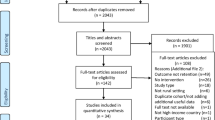

The review focuses on two types of intervention strategies: compulsory rural services programmes and direct and indirect financial incentives. The target population may include both existing health professionals and medical students. Studies were included in the analysis when context or process information of the interventions was discussed. Literatures were excluded if the papers had no introduction of interventions or if interventions were not about compulsory rural service programmes and financial incentives. Two reviewers independently assessed potential studies for inclusion and resolved disagreements through discussion. The study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Data collection and analysis

A standard data extraction form was used to extract data on study characteristics (title, author, year and study methods), intervention design, effectiveness and context factors. Information on context issues and process were coded and grouped into three levels: 1) macro-level context factors include political, economic and social factors; 2) meso-level context factors include health system factors; and 3) micro-level context factors refer to the implementation process.

We assessed the methodological quality of the included studies with the criteria developed by Hawker and colleagues [11,12]. We used eight dimensions for quality assessment. For each dimension, we rated the quality of included studies from 1 (good) to 4 (very poor). The overall methodological quality for each study was calculated using the average score of the eight dimensions. Then the quality of included studies was grouped into four levels (1.00–1.49 = good; 1.50–2.49 = fair; 2.50–3.49 = poor; 3.50–4.00 = very poor) [12].

In total, 40 studies were included in this review, as shown in Table 1 [1,6,13-50]. Twenty-five studies were rated “good” in methodological quality, 11 “fair”, 3 “poor” and 1 “very poor”. The context factors are reported in Table 2.

Results

Study characteristics

Fifteen studies were from high-income countries, 20 from low- and middle-income countries and 5 from a mixture of both. Eighteen studies were descriptive studies (no design study, just a plain description of the interventions, context factors, implementation process or effectiveness). Other study designs included cohort study (10), cross-sectional survey (6), qualitative study (4), case–control study (1) and cost–benefit analysis (1).

Interventions and effectiveness

In the selected studies, there were four broad types of xfinancial incentives: scholarship, loan, loan repayment and direct financial incentives. These financial incentive and compulsory rural service programmes were usually combined together. Effectiveness of these interventions was mixed. Studies in Japan and USA showed that financial incentives (scholarship and loan repayment) together with compulsory rural service programmes were successful in improving the attraction and retention of rural health workers [26-36,33-35], while studies in Zambia showed that the health worker retention scheme did not meet its policy objectives to address the shortage of rural health workers [49,50].

Macro-level context factors

Political factors

Six out of 40 studies reported political factors relevant to the interventions (Table 2). A post-conflict situation after civil war usually meant fragile health systems and shortfall of resources including HRH [1]. The timing of introducing a rural allowance policy to address geographical inequities in health personnel distribution in South Africa right before its second democratic election in 2004 suggested a political motive [20]. Social movement towards equity in South Africa after the abolishment of apartheid [23] and in Thailand [46] draws more attention to the HRH disparity between urban and rural areas.

Economic factors

Fifteen out of 40 studies reported economic factors. Interventions, especially the financial incentives, require financial commitments. The fiscal capacity of a country or organization may largely affect not only its enthusiasm to address HRH problems but also its actual choices. In high-income countries such as Australia and Chile, compensation for tuition fees can be from 5000 to 10 000 US dollars per year [25,36], while in many African countries, a popular intervention was to provide moderate lunch or transportation allowance [47].

Another economic-related factor is the rising cost of medical education. This is particularly a concern in the USA where the tuition fees for medical students are extremely high. More than 80% of medical students carried educational loans after graduation. Looming training debt may force some young physicians into the higher paying, non-primary care specialties and thereby undermining national efforts to expand the primary care workforce. In this context, the loan repayment programme became increasingly popular to young medical graduates with training debt. The programme pays for their loan on a regular basis while in return the medical graduates provide service in rural areas. It was reported that one quarter of medical graduates committed to this support-for-service programme [33]. As the medical education is gradually opened to the private sector and consequently the escalating cost for medical training that is happening in many countries such as Thailand [45], loan and loan repayment programmes may become a suitable intervention to attract and retain rural health workers.

Social factors

Seven out of 40 studies reported social factors. Social culture and ethics are other factors to be considered in intervention design. In some Asian countries, there is a cultural reluctance to borrow money from outside the circle of family relatives [51]. This may make a loan repayment programme infeasible in that context. In Ecuador and Bolivia, there was a social belief that health professionals should compensate for the free medical education they received by serving in the rural areas [17]. Helping the local community after graduation was also the motivation for some South African medical students to choose a rural job [40]. However, forcing young physicians into rural work can demoralize them. Controversy concerns were raised about whether mandatory service was ethically acceptable [45].

Meso-level context factors

Deficit and maldistribution of health workforce

Deficit and maldistribution of health workforce are the essential background factors which initiate the whole idea of attraction and retention. Thirty-four out of 40 studies reported health workforce maldistribution. For example, in South Africa, there was big gap between urban and rural areas due to the internal migration of health workers [23]. In Indonesia, only 20% of doctors are located in rural areas, serving 70% of the population [31]. As a consequent, both countries introduced interventions including rural allowances and other financial incentives to address the HRH problems.

Private health services

Ten out of 40 studies reported context factors related to private health services. Many countries have a long history of public services. In Thailand, a unique public service system assured that all medical graduates worked as government employees to provide medical care at public health facilities. In 1968, the Thai government set high medical education fees for public medical schools and launched a programme of mandatory rural service which required all medical graduates to work at public medical facilities for at least 3 years in exchange for a waiver of tuition fee [32,44].

Although public service is still the mainstream choice in some countries, things have changed in the past decades. Increasing number of private medical schools and the promotion of private health care enforced competition for certain medical specialties. In Thailand, the number of new private hospitals had a 3.3-fold increase in 10 years from 1000 in 1985 to 3300 in 1995 [45]. These private hospitals drained physicians from the mandatory rural public service system.

Decentralization of health system

Decentralization of the health system can be defined as the transfer of authority, or disposal of power, in health planning, management and decision-making from a higher to lower level of government [52]. Six out of 40 studies reported context factors related to decentralization which can provide states/districts with wider choice and greater flexibility to better meet the needs of local communities. In Zambia, a decentralization policy was reported to drastically change the labour relations in the health sector [24]. Senegal decentralized public schools for more local training and recruitment of health workers [48].

Health financing

Five out of 40 studies reported health financing as another health system factor. Thailand introduced universal health coverage in 2001 and introduced capitation-based payment reform for outpatient services. This created a strong incentive for more equitable distribution of HRH [44]. Introduction of user fees in Uganda in the 1990s motivated doctors to jobs with high pay and better working conditions [1].

Micro-level factors

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E)

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) help monitor the implementation progress, identify and address emerging problems and track the intervention outputs and outcomes. Ten out of 40 studies introduced their efforts on M&E. There was often lack of information on how well the interventions were implemented [41]. Sometimes, these programmes even tended not to formally evaluate themselves or document their successes, as they often lacked the funds, expertise and mandate to do so [33].

Consultation and engagement of actors

There is no clear picture of how different actors were consulted and involved in the policy process. Twenty-six out of 40 studies reported this factor. Although, in some countries, it was reported that wide consultations were conducted during the policy process [24], in most cases, the process was considered weak and uncoordinated [20]. In Chile, trade unions emerged as strong lobby groups in the policy process [36].

Government bodies including health- or education-related authorities were commonly responsible for implementing the interventions. In a USA study, most programmes were administered by state education and finance authority. Other uncommon administration organizations included non-profit corporations, medical or nursing schools [35].

Funding sources

Twenty-two out of the 40 studies identified sources of intervention funding. In high-income countries, one key issue of funding is the balance between central and local governments. Pathman et al. reported that most programmes (n = 13) in the USA were funded by state legislatures using general tax revenues; 4 were entirely federally funded [35]. In Japan, Jichi Medical University had run a model programme with the combination of scholarship and compulsory rural service since 1972. This programme was equally funded by 47 prefecture governments in Japan [27].

Many low-income countries had to rely on international funding to support their intervention programmes. International funding may provide opportunity for the low-income countries to afford the costly interventions, although not all donors are willing to do so.

There were some additional funding sources, including buyout funds from earlier participants, private non-profit organizations [35] or even tax levies from nursing licence applications [42].

Legislation process of intervention strategies

Seven out of 40 studies reported legislation process in the policy development and implementation process. Some countries implemented the financial incentives and compulsory rural service programmes in the format of law. Most states in the USA had such a law. In Chile, one of the landmarks in the implementation of the Rural Practitioner Programme was the enactment of Law 15076 in 1963 which was reformed into Law 19664 in the year 2000 [36]. The main interventions in the Rural Practitioner Programme were a paid residency in a university hospital plus attractive salaries and benefits. The law granted autonomy from political support and ensured sustainability of the programme over time. It also established a secure financing mechanism.

Discussion

Although context factors are widely considered important in the literature, these factors are rarely reported and analysed systematically. The context factors presented in this review are derived only from the available literature which may not necessarily cover all relevant context factors, due to lack of research in this specific area. For example, limited evidence was found to discuss the role of universal health coverage policy and health worker attraction and retention [53].

Although the selected studies in this review reported different context factors, there is very limited information in the original studies analysing whether or not these context factors have positive or negative influence on the development and implementation of the strategies. The review tries to discuss the potential influence of different context factors on the various policy stages.

Policy analysts usually tend to break down health policy process into a series of stages though acknowledging this does not necessarily reflect the exact process in the real world [54]. This theoretical model usually consists of agenda setting, policy formulation and policy implementation. The context factors identified in this review may have certain influence on different stages of the policy cycle, as discussed below.

Meso-level factors can play a critical role during the agenda-setting stage. In the area of attraction and retention of health workers, analysing the situation of health workforce distribution between different regions should be the first step of policy analysis. Other health system factors should also be considered when interpreting the maldistribution of health workers between. For example, the growing private sector is one of the forces attracting health workers to urban area [55]. A decentralized health system may promote more dynamic flows of health workers in the labour market, in which case the rural areas are in a disadvantaged position to attract and retain their health workers due to their disadvantages in working and living conditions [56].

Macro-level factors should be carefully considered during the policy formulation stage. In different political systems, the governing body may have special preference for financial incentive interventions or compulsory regulations in order to address the deficit of health workers in rural areas. The choice of intervention strategies will largely depend on the economic development and financial capacity of the central or local government. Policy formulation process should also carefully consider the social acceptance of potential interventions, according to their specific social culture and values.

Micro-level factors that are essential in policy implementation and evaluation stage usually do not receive sufficient attention [57]. Stakeholders are not always properly consulted and involved in the policy implementation process. M&E are no doubt one of the most important parts of the intervention programme. Without M&E, one cannot tell how the intervention is implemented, cannot solve emerging problems during the implementation and cannot track the outputs and outcomes of the interventions. However, most of the interventions are not rigorously monitored and evaluated. Furthermore, funding sources may not be sustainable to implement these policies.

The relationships described above regarding the context factors and different stages of policy process are not exhaustive. There might be other direct and indirect relationships between the context factors and the policy stages. For example, in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions, one may also need to consider the macro-level factors (political and economic factors) and meso-level factors (health system factors) in interpreting why some intervention strategies work well in this country context but not in other settings.

Macro-, meso- and micro-level context factors should be carefully considered when formulating, implementing and evaluating strategies to attract and retain health workers in rural areas. This review may help low- and middle-income countries to properly adopt WHO-recommended strategies [5]. First, they need to analyse their specific health system to assess the distribution of health professionals and investigate the root causes in health system. While adopting internationally proven intervention strategies, local social, economic and political factors should be checked to ensure applicability and transferability [58]. Last but not least, a carefully designed implementation and evaluation plan is crucial for the success of any interventions to attract and retain health workers to rural and remote areas.

References

Dambisya YM. A review of non-financial incentives for health worker retention in East and Southern Africa: East, Central and Southern African Health Community (ECSA-HC). South Africa: University of Limpopo; 2007 [http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/equinet_incentives/en/]. Access 18 July 2015.

Campbell J. The route to effective coverage is through the health worker: there are no shortcuts. Lancet. 2013;381:725.

Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet JM. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:379–85.

National Rural Health Student Network. Bonded medical places and medical rural bonded scholarships: position paper. Melbourne. 2010. [http://www.nrhsn.org.au/advocacy/position-papers/]. Access 18 July 2015.

WHO. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [www.who.int/hrh/retention/guidelines/en/]. Access 18 July 2015.

Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE. Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:86.

Dieleman M, Gerretsen B, Van Der Wilt GJ. Human resource management interventions to improve health workers’ performance in low and middle income countries: a realist review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7:7.

Leichter HM. A comparative approach to policy analysis: health care policy in four nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1979.

Collins C, Green A, Hunter D. Health sector reform and the interpretation of policy context. Health Policy. 1999;47:69–83.

Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur RE. Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:207–17.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1284–99.

Groene O, Botje D, Suñol R, Lopez MA, Wagner C. A systematic review of instruments that assess the implementation of hospital quality management systems. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:525–41.

Adjei GA. Improving staff retention in Ghana. Health Exchange 2009. [http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/3032]. Access 18 July 2015.

Baumann A, Yan J, Jaclyn Degelder J, Malikov K. Retention strategies for nursing: a profile of four countries. NHSRU; 2006. [http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/1205]. Access 18 July 2015.

Bhattacharyya K, Winch P, LeBan K, Tien M. Community health worker incentives and disincentives: how they affect motivation, retention, and sustainability. Virginia: BASICS II; 2001 [http://www.chwcentral.org/community-health-worker-incentives-and-disincentives-how-they-affect-motivation-retention-and]. Access 18 July 2015.

Caffrey M, Frelick G. Health workforce “Innovative approaches and promising practices” study: attracting and retaining nurse tutors in Malawi. Capacity Project: USAID; 2006 [https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/hrh/health-workforce-innovative-approaches-and-promising-practices-study-attracting-and]. Access 18 July 2015.

Cavender A, Alban M. Compulsory medical service in educator: the physician’s perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1937–46.

Chomitz KM, Setiadi G, Azwar A, Ismail N, Widiyarti. What do doctors want? Developing incentives for doctors to serve in Indonesia’s rural and remote areas. [http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/what_do_doctors_want/en/]. Access 18 July 2015.

De Arellano ABR. A health “draft”: compulsory health service in Puerto Rico. J Public Health Policy. 1981;2:70–4.

Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Bidwell P, Thomas S. Analyzing the implementation of the rural allowance in hospitals in North West Province. South Africa J Public Health Policy. 2011;32 Suppl 1:S80–93.

Duttera Jr MJ, Blumenthal DS, Dever GE, Lawley JB. Improving recruitment and retention of medical scholarship recipients in rural Georgia. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000;11:135–43.

Efendi F. Health worker recruitment and deployment in remote areas of Indonesia. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2008.

George G, Atujuna M, Gow J. Migration of South African health workers: the extent to which financial considerations influence internal flows and external movements. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:297.

Koot J, Martineau T. Mid-term review: Zambian Health Workers Retention Scheme (ZHWRS) 2003-2004. Chapel Hill: HRH Global Resource Center; 2005 [http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/hosted_docs/Zambian_Health_Workers_Retention_Scheme.pdf]. Access 18 July 2015.

Laven GA, Wilkinson D, Beilby JJ, McElroy HJ. Empiric validation of the rural Australian Medical Undergraduate Scholarship ‘rural background’ criterion. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13:137–41.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. Long-term effect of the home prefecture recruiting scheme of Jichi Medical University, Japan. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8:930.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. A contract-based training system for rural physicians: follow-up of Jichi Medical University graduates (1978-2006). J Rural Health. 2008;24:360–8.

Matsumoto M, Kajii E. Medical education program with obligatory rural service: analysis of factors associated with obligation compliance. Health Policy. 2009;90:125–32.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E, Takeuchi K. Retention of physicians in rural Japan: concerted efforts of the government, prefectures, municipalities and medical schools. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1432.

Matsumoto M, Inoue K, Kajii E. Policy implications of a financial incentive program to retain a physician workforce in underserved Japanese rural areas. Soc Sci Med. 2010;7:667–71.

Meliala A, Hort K, Trisnantoro L. Addressing the unequal geographic distribution of specialist doctors in Indonesia: the role of the private sector and effectiveness of current regulations. Soc Sci Med. 2013;82:30–4.

Pagaiya N, Noree T. Thailand’s health workforce: a review of challenges and experiences. [http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/3582]. Access 18 July 2015.

Pathman DE, Taylor Jr DH, Konrad TR, King TS, Harris T, Henderson TM, et al. State scholarship, loan forgiveness, and related programs: the unheralded safety net. JAMA. 2000;284:2084–92.

Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Spaulding C, Taylor DH. Medical training debt and service commitments: the rural consequences. J Rural Health. 2000;16:264–72.

Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Taylor Jr DH, Koch GG. Outcomes of states’ scholarship, loan repayment, and related programs for physicians. Med Care. 2004;42:560–8.

Peña S, Ramirez J, Becerra C, Carabantes J, Arteaga O. The Chilean rural practitioner program: a multidimensional strategy to attract and retain doctors in rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:371–8.

Reid S. Monitoring the effect of the new rural allowance for health professionals. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004 [http://healthlink.org.za/uploads/files/rural_allowance.pdf]. Access 18 July 2015.

Renner DM, Westfall JM, Wilroy LA, Ginde AA. The influence of loan repayment on rural healthcare provider recruitment and retention in Colorado. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1605.

Ross AJ, Couper ID. Rural scholarship schemes: a solution to the human resource crisis in rural district hospitals? South African Fam Pract. 2004;46:5–6.

Ross AJ. Success of a scholarship scheme for rural students. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:1087–90.

Shroff ZC, Murthy S, Rao KD. Attracting doctors to rural areas: a case study of the post-graduate seat reservation scheme in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Commun Med. 2013;38:27–32.

Thaker SI, Pathman DE, Mark BA, Ricketts TC. Service-linked scholarships, loans, and loan repayment programs for nurses in the southeast. J Prof Nurs. 2008;24:122–30.

Weiss LD, Wiese WH, Goodman AB. Scholarship support for Indian students in the health sciences: an alternative method to address shortages in the underserved area. Public Health Rep. 1980;95:243–6.

Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1:12.

Wiwanitki V. Mandatory rural service for health care workers in Thailand. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1583.

Wongwatcharapaiboon P, Sirikanokwilai N, Pengpaiboon P. The 1997 massive resignation of contracted new medical graduates from the Thai Ministry of Public Health: what reasons behind? Human Resour Health Deve J. 1999;3:147–56.

Yumkella, F. Worker retention in human resources for health: catalyzing and tracking change; Capacity Project knowledge sharing 2009. [http://www.intrahealth.org/page/worker-retention-in-human-resources-for-health-catalyzing-and-tracking-change]. Access 18 July 2015.

Zurn P, Codjia L, Sall FL, Braicheta JM. How to recruit and retain health workers in underserved areas: the Senegalese experience. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:386–9.

Gow J, George G, Mwamba S, Ingombe L, Mutinta G. An evaluation of the effectiveness of the Zambian Health Worker Retention Scheme (ZHWRS) for rural areas. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:800–7.

Goma FM, Tomblin Murphy G, MacKenzie A, et al. Evaluation of recruitment and retention strategies for health workers in rural Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12 Suppl 1:S1.

Salmi J. Student loans in an international perspective: the World Bank experience. [http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLL/Resources/student_loans.pdf]. Access 18 July 2015.

Mills A, Vaughan JP, Smith DL, Tabibzadeh I. Health system decentralization: concepts, issues and country experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990.

Thoresen SH, Fielding A. Universal health care in Thailand: concerns among the health care workforce. Health Policy. 2011;99:17–22.

BuseK MN, Walt G. Making health policy. UK: Open University Press; 2005.

Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Jongudomsuk P. Achieving coverage in Thailand: what lessons do we learn? Health Systems Knowledge Network. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Liu X, Martineau T, Chen L, Zhan S, Tang S. Does decentralisation improve human resource management in the health sector? A case study from China. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1836–45.

Green A, Gerein N, Mirzoev T, et al. Health policy processes in maternal health: a comparison of Vietnam. India and China Health Policy. 2011;100:167–73.

Wang S, Moss JR, Hiller JE. Applicability and transferability of interventions in evidence-based public health. Health Promot Int. 2006;21:76–83.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review is funded by WHO Alliance for Health Policy and System Research. We owe our thanks to Professor Gilles Dussault for his great comments on the first draft of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed to the production of this manuscript. XL, LD and BY discussed and contributed to conceptualization of this review and development of review protocol. BY guided the use of systematic review method. LD, HZ, YS and BY applied the inclusion criteria, data extraction and quality assessment. XL prepared the first draft and all other authors commented on and revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Dou, L., Zhang, H. et al. Analysis of context factors in compulsory and incentive strategies for improving attraction and retention of health workers in rural and remote areas: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 13, 61 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0059-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0059-6