Abstract

Background

Previous studies, which were primarily based on the fluorescent in-situ hybridisation (FISH) technique, revealed conflicting evidence regarding male foetal microchimerism in endometriosis. FISH is a relatively less sensitive technique, as it is performed on a small portion of the sample. Additionally, the probes used in the previous studies specifically detected centromeric and telomeric regions of Y chromosome, which are gene-sparse heterochromatised regions. In the present study, a panel of molecular biology tools such as qPCR, expression microarray, RNA-seq and qRT-PCR were employed to examine the Y chromosome microchimerism in the endometrium using secretory phase samples from fertile and infertile patients with severe (stage IV) ovarian endometriosis (OE) and without endometriosis.

Methods

Microarray expression analysis followed by validation using RNA-seq and qRT-PCR experiments at the RNA levels and further validation at the DNA level by qPCR of target inserts for selected targets in eutopic endometrium samples obtained from control (CON) and stage IV ovarian endometriosis (OE), either from fertile (FCON and FOE; n = 30/each) or infertile (ICON and IOE; n = 30/each) women, were performed.

Results

Six coding (AMELY, PCDH11, SRY, TGIF2LY, TSPY3, and USP9Y) and 10 non-coding (TTTY2, TTTY4C, TTTY5, TTTYY6, TTTY8, TTTY10, TTTY14, TTTY21, TTTY22, and TTTY23) genes exhibited a bimodal pattern of expression characterised by low expression in samples from fertile patients and high expression in samples from infertile patients. Seven coding MSY-linked genes (BAGE, CD24, EIF1AY, NLGN4Y, PRKY, VCY and ZFY) exhibited differential regulation in microarray analysis, and this change was validated by RNA-seq or qRT-PCR. DNA inserts for 7 genes in various samples were validated by qPCR. The prevalence and concentration of PCR-positive target inserts for BAGE, PRKY, TTTY9A and ZFY displayed higher values in the fertile, control (FCON) patients compared with the fertile, endometriosis patients (FOE).

Conclusion

Several coding and non-coding MSY-linked genes displayed microchimerism as evidenced by the presence of their respective DNA inserts, along with their differential transcript expression, in the endometrium during endometriosis and in cases of infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

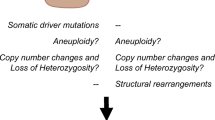

Amongst several theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis, Sampson’s theory postulating that viable endometrial cells deposited at ectopic sites due to retrograde menstruation implant, grow and eventually result in the histogenesis of endometriosis has received wide acceptance [1]. Although retrograde menstruation and exfoliated endometrial cells in the peritoneal cavity are reportedly present in most cycling women, approximately 10% of women in the reproductive age group suffer from endometriosis [1, 2]. It is therefore conjectured that there are other factors possibly at play in the endometrium that predispose a subgroup of women towards the histogenesis of endometriosis at ectopic sites. Several lines of evidence indeed support the notion that some intrinsic defects in the eutopic endometrium are responsible for the resultant endometriosis [3,4,5]. Substantial evidence suggest that women with endometriosis bear an increased risk of developing autoimmune diseases [6,7,8]. However, several autoimmune diseases are reportedly associated with male microchimerism [9,10,11]. Taken together, it appears that male microchimerism in the eutopic endometrium may be a supplementary factor towards the histogenesis of endometriosis at ectopic sites. A few transcripts related to Y-chromosomal genes were recorded in the secretory phase of eutopic endometrial samples obtained from patients with stage-confirmed endometriosis [12, 13]. Additionally, direct evidence of male microchimerism in endometriosis was earlier reported in a study [14]. Fassbender et al., however, failed to obtain evidence of such male microchimerism in the endometrium based on FISH-based experiments in a total of 31 patients, of which 19 had stage-confirmed endometriosis [15]. In the present study, we have examined this issue of Y-chromosomal microchimerism in fertile and infertile women with ovarian endometriosis (OE), without any reported uterine pathology. This was achieved using a sequence of experiments that included microarray expression followed by RNA-seq and quantitative RT-PCR experiments at the RNA levels and further validation at the DNA level by quantitative PCR of target inserts for selected targets (see Fig. 1 for the study design).

A schematic flow chart of the study design. Genomic evidence of Y chromosome microchimerism in the endometrium in endometriosis and infertility was probed first by examining Y chromosome-centric transcript expression data from whole genome microarray experiments and from whole genome RNA-seq data followed by validation at the RNA level by quantitative RT-PCR and the DNA level by quantitative PCR

Methods

Patient selection and sample collection

Patients enrolled in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences New Delhi (AIIMS-D) for surgical intervention of endometriosis, in the Infertility Clinic or for family planning voluntarily took part in the study after understanding its purpose and giving written consent as per the standard protocol. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on the Use of Human Subjects and conducted as per the Helsinki Declaration of 2013. There were two groups. The control group (CON; age: 35.7 ± 3.2 years) was comprised of proven fertile and normocyclic women who were undergoing either voluntary sterilisation, or hysterectomy for issues other than uterine diseases (FCON; n = 30), and women who were attending the infertility clinic (ICON; n = 30). The ovarian endometriosis group (OE; age: 37.2 ± 4.5 years) was comprised of women who were proven fertile (FOE; n = 30) or infertile, (IOE; n = 30) with confirmed stage IV ovarian endometriosis but having no report of recurrence of the disease or any other endocrinological disorder or other complications of comorbidities and who were enrolled for surgical intervention. Patients of both groups had normal BMI (20–25). Table 1 provides a summary of group-wise distribution of number of patients for different experiments, as well as the gender of offspring obtained from compliant women in FCON and FOE. The outline of the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Tissue processing

Secretory phase endometrial samples were collected in PBS (pH 7.4) on ice and transported to the laboratory for immediate processing. Tissues to be used for qPCR, expression microarray, RNA-seq and qRT-PCR experiments were immediately processed for DNA and RNA extraction. RNA samples with a RIN score ≥ 8.0 were further used in expression microarray, RNA-seq and qRT-PCR experiments to determine the transcript levels as described below.

Expression microarray and differential expression analysis

RNA extraction, followed by expression microarray experiments using 4 × 44 k whole genome expression microarray printed slides and Agilent platform and supplies (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA), was done as described in other studies [13, 16]. The high-resolution images were subjected to feature extraction using Agilent Feature Extraction software v10.7.3.1. Expression microarray data were log2 transformed and normalised to the 75th percentile for further analysis of expressed genes on the Y chromosome. The resulting gene lists were used as input data for statistical analysis as described below. The data have been archived at GSE120103.

RNA-Seq

Nucleotide sequencing experiment for extracted RNA was done according to Trapnell et al. [17]. Total RNA samples were subjected to ribosomal RNA and other RNA removal using an oligo-dT for purification followed by fragmentation. Subsequently, they were copied into first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers followed by a second strand cDNA synthesis using a reverse transcriptase enzyme. Fragments were purified with SPRI beads and subjected to an end-repair process. The cDNA libraries were generated following ligation with multiple indexing adapters to the ends of the ds-cDNA. Libraries were validated using BioAnalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) after enrichment with PCR followed by pooling and normalisation. This was followed by enrichment of ligated cDNA molecules, preparing them for hybridisation onto a flow cell for the sequencing run on Illumina HiSeq2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using sequencing by synthesis chemistry. cDNA was passed through flow cells where it hybridised to the complementary sequences of adaptors. Amplification of the sequences was done using bridge amplification followed by clonal amplification and a sequencing reaction was performed using reversible dye termination chemistry following MINSEQE guidelines. The sequenced reads were obtained using the pair-end sequencing method and subjected to further analysis [17].

For analysis of RNA-seq data, the sequenced raw reads in FastQ format were first checked for low confidence bases, biased nucleotide composition, adapters, and duplicates and were further subjected to preprocessing. Q10 scores were determined from a Q table and poor-quality reads were filtered out from the downstream analysis using FastQC (Cambridge, CB22 3AT, UK). The selected reads were further subjected to alignment based on Human Reference Genome v19 using BowTie software (Baltimore, MD, USA), as described earlier [17, 18]. The referenced data in the BAM file was further analysed for its percentage match with the reference genome [19]. Only Y chromosome mapped reads were annotated and further selected, normalised and analysed as described below.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Real time RT-PCR using SYBR-green chemistry was done using platform and chemicals obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA) to validate the differentially expressed transcripts obtained by expression microarray following the MIQE protocol [20]. Relative expression of selected genes along with that of endogenous control genes (B-ACTIN, B2M, GAPDH and UBC) in control and eutopic samples was assessed using BioRad CFX 96 Real Time PCR system. The methodological details have been described in other studies [13, 16, 21]. The primers for the target genes, as shown in Additional file 1 Table S1, were designed using Beacon Designer (Premier Biosoft, CA, USA) and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA).

PCR detection for target DNA

DNA specimens extracted as previously described [22] were used for quantitative PCR to quantify the DNA copy numbers of the following genes: BAGE, EIF1AY, KDM5D, NLGN4Y, PRKY, TTTY9A, TTTY14, SRY and ZFY using SYBR-green chemistry with the abovementioned PCR system. Archival colon DNA (n = 4) and blood DNA (n = 4) samples from men were used as known positive control for Y chromosome genes. Quantitative assessment of DNA in terms of copy number of inserts were calculated using the standard curve constructed from the serially diluted PCR products of the ZFY gene segment of 490 bp at chromosomal location Yp11.2 [19]. The primers for the target genes, as shown in Additional file 1 Table S1, were designed using Beacon Designer software (Premier Biosoft, CA, USA). Specific nucleotide sequences were provided by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA).

Data analysis

The microarray data were statistically analysed using Welch ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing corrections for false discovery rate to identify differentially expressed (DE) genes having > 2-fold at P < 0.05 in pair-wise comparisons. All data processing and analysis were performed using the GeneSpring software v14.9.1 (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). Differential expression for RNA-seq data for Y chromosome mapped reads were analysed using the software DESeq v1.31.0 (Bioconductor Package, Buffalo, NY, USA). Differentially expressed genes were subjected to the Wald test followed by a Benjamini-Hochberg correction. A cut-off value of > 2-fold change and P < 0.05 were used to report the final list of significantly differentially expressed genes. Inter-group differences in quantitative RT-PCR were calculated as described previously [20]. For statistical analysis of prevalence, the Fisher’s exact test was performed. For non-Gaussian data, the Mann-Whitney U-test was applied, using SPSS v16.0 (IBM Analytics, New York, US).

Results

General

Table 1 reveals that approximately 40% of fertile patients with stage IV OE and with no uterine pathology reportedly had at least one male child, while 10% of fertile control patients and 20% of fertile patients with OE declined to provide the information about the gender of their children. However, as detailed in the following sections, endometrial samples from patients with and without endometriosis, irrespective of their clinical histories of pregnancy, displayed detectable DNA inserts and transcript expressions of Y chromosome-linked genes.

Transcript expression

In whole genome expression microarray experiments, transcript expression of fifty-four (54) human male-specific regions of the Y chromosome (MSY) genes present in an ampliconic region of the Y chromosome were detected, and included 33 coding and 21 non-coding genes (Table 2). Interestingly, six (6) coding (AMELY, PCDH11, SRY, TGIF2LY, TSPY3, and USP9Y) and ten (10) non-coding (TTTY2, TTTY4C, TTTY5, TTTYY6, TTTY8, TTTY10, TTTY14, TTTY21, TTTY22, and TTTY23) genes exhibited a common bimodal pattern of expression characterised by low expression in samples from fertile patients while high expressions were associated with infertility (Fig. 2).

A typical bimodal pattern of transcript expression in data from microarray experiments characterised by low expression in samples from fertile patients and high expressions associated with infertility for six (6) coding (AMELY, PCDH11, SRY, TGIF2LY, TSPY3, and USP9Y) genes and ten (10) non-coding (TTTY2, TTTY4C, TTTY5, TTTYY6, TTTY8, TTTY10, TTTY14, TTTY21, TTTY22, and TTTY23) RNA genes. Control values are shown as blank bars and values for ovarian endometriosis are shown as grey bars

As Table 3 reveals, expression microarray experiments identified a total of 18 coding MSY-linked genes showing differential expression in different groups; 5 genes (BAGE, EIF1AY, NLGN4Y, PRKY and ZFY) of those 18 genes could be detected in both RNA-seq and real time RT-PCR, while expression of additional two (2) genes (CD24 and VCY) could be detected in real time RT-PCR, but not in RNA-seq. Thus, 11 coding genes (AMELY, BPY2B, CDY2A, DDX3Y, DAZ2, HSFY2, KDM5D, TBL1Y, TGIF2LY, TSPY3, and XKRY2) linked with the Y chromosome that exhibited a differential display in the between-groups comparisons of data obtained from expression microarrays, could not be detected by RNA-seq and quantitative RT-PCR. Twenty-one (21) non-coding Y chromosome-linked genes did not exhibit any differential display in the between-groups comparisons of data obtained from RNA-seq and RT-PCR (data not shown).

Target DNA inserts

Quantitative PCR for identifying DNA targets for nine (9) MSY-linked genes revealed positive results for seven (7) genes in various samples, two (KDM5D and SRY) however were undetectable (Table 4). Furthermore, the prevalence and concentration of PCR-positive target inserts displayed generally higher trends in the fertile, control (FCON) patients compared with the other three groups (ICON, FOE and IOE); however, significantly higher values were obtained in the fertile, control (FCON) patients only when compared with the fertile, OE patients (FOE) for the prevalence of BAGE, PRKY, and TTTY9A and for the concentration of ZFY.

Discussion

A panel of molecular biology tools including quantitative PCR, microarray expression, RNA-seq, and real time RT-PCR were employed to examine the Y chromosome microchimerism in the endometrium using secretory phase samples from fertile and infertile patients with severe OE (stage IV) and without endometriosis. This experimental strategy was adopted since earlier studies using FISH yielded conflicting results [14, 15]. FISH is a relatively less sensitive technique and it probes into a very small portion of the sample [22,23,24,25]. Furthermore, two probes used in the previous FISH study to detect the Y chromosome in endometrial cells were directed against the centromeric (Yp11.1 to Yq11.1) and telomeric (Yq12 satellite) regions of the Y chromosome [15]. Both these regions are gene-sparse heterochromatised regions of the Y chromosome. In the present study, the DNA segments detected are from the ampliconic regions of the Y chromosome. Moreover, it is generally believed that chromosome-centric quantitative expression data bear robust relevance towards understanding the deep physiology of cells and tissues [26, 27].

A consolidated summary of the results of the present study is presented in Table 5. The results of our study revealed that male microchimerism in the endometrium is widely present in all groups of patients irrespective of endometriosis and pregnancy history. A large number of reports indeed substantiate the notion of the widespread presence of male microchimerism in human females [28,29,30,31,32].

It is apparent from the present study that Y chromosome microchimerism in the endometrium in general did not show any marked relationship with pregnancy history, as it was observed in both fertile and infertile patients with and without disease. Furthermore, the assumption that Y chromosome microchimerism evolves with a higher prevalence in women from pregnancies with sons [33,34,35] could not be empirically assessed in the present study as half of the fertile women had at least one son and one-fifth declined to report the details of the gender of their offspring. However, we did not observe any marked indication of such association from the present set of data. Indeed, earlier reports indicated that male microchimerism was seen among women without any son; in fact, 10% of them had never been pregnant before [36]. It has been suggested that microchimerism is not only limited to the bi-directional exchange of cells between mother and foetus but also cells from older siblings and even maternal grandmother cells may also be transferred to the foetus and can persist in various tissues for a long period of time [22, 33, 37,38,39,40].

Furthermore, our study reveals interesting observations regarding the prevalence and concentration of observed DNA inserts of the Y chromosome, particularly vis-à-vis their transcriptional expression in the endometrium. PCR experiments for quantifying DNA inserts of the Y chromosome revealed a lower prevalence and concentration of male microchimerism in diseased eutopic tissues; however, their steady state expressions were higher. In contrast, the prevalence and concentration of male microchimerism was higher with lower transcript expressions in the control endometrial samples. Chan et al. also observed a lower prevalence and concentration of male microchimerism in the brains of women with Alzheimer’s disease when compared to the brains of women without neurologic disease [34]. Sawaya et al. observed, using quantitative PCR, that all systemic sclerosis (SSc) samples were positive for male DNA compared with higher levels of microchimerism in clinically unaffected SSc skin [22]. In fact, several groups have indicated the possibility that foetal microchimerism may actually render a benefit to the mother’s health in certain conditions [32, 39, 41,42,43,44,45,46].

Figure 3 provides the physical map of the 54 genes detected by microarray in a typical Y chromosome. According to the available database, the Y chromosome is approximately 60 Mb in size and consists of the male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY), which contains 73 protein-coding genes and 122 non-coding RNA genes and two small pseudoautosomal regions flanking each side (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Based on gene ontology (GO) analysis, the molecular function of proteins potentially arising from those 54 microarray-positive transcripts of the Y chromosome in patients can be predicted. Those predications are categorised into protein binding, DNA binding, RNA binding, metal ion binding, transcription factor activity, transcription regulator activity, transferase activity, ATP binding, translation activity, esterase activity, oxidoreductase activity, kinase activity, protease activity and helicase activity (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA). In terms of biological processes in GO analysis, the proteins of those transcripts are involved in transcription, cell differentiation, gonad development, metabolic processes, tissue development, nucleosome assembly, chromatin modification, translation, sex differentiation, cell adhesion, RNA metabolism, cell proliferation and sex determination (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA).

Physical map of human male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY) with markings of cytogenic bands for genes in ampliconic sequences that were observed to display very high to very low levels of transcript expression (as shown by colour codes) in expression microarray experiments with endometrial samples obtained from fertile and infertile women of control (CON) and ovarian endometriosis (OE) groups. Heat map depicts mean transcript expressions of MSY-linked genes detected in whole genome expression microarrays with secretory phase endometrium. Different colour codes in boxes for different classes of sequences in MSY-linked genes, and colour spectrum for expression ranges are shown

In the present study, a few Y chromosome-linked long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the endometrium were detected at both the DNA and RNA levels. As expected, their signals were generally in the lower scale, except for TTTY14 which displayed a high order of prevalence and concentration in all samples. The significance of this observation is open to further study. It is now well acknowledged that the human genome contains a large number of lncRNAs and that this subset of non-coding RNAs accomplish a remarkable variety of biological functions [47,48,49,50]. Although there is a growing interest about the potential role of various lncRNAs in endometriosis and infertility, [51,52,53] and more specifically the possible association between Y chromosome-linked lncRNAs (for example, lncKDM5D) and fat metabolism and cellular inflammation in the causation of atherosclerosis and CAD in men, [46] we have no understanding about the possible involvement of specifically the MSY-linked lncRNAs in endometriosis and in infertility.

It appears intriguing that several coding (AMELY, PCDH11, SRY, TGIF2LY, TSPY3, and USP9Y) and non-coding (TTTY2, TTTY4C, TTTY5, TTTYY6, TTTY8, TTTY10, TTTY14, TTTY21, TTTY22, and TTTY23) genes commonly displayed low expression in samples from fertile patients and high expression in samples from infertile patients with very little influence of OE on their expression profile. It appears that MSY-linked transcript expressions showed marked association with infertility. In this regard, it is noteworthy that mere microchimerism may be of minimal consequence, as it is rather a frequent phenomenon in women who have carried foetuses, as well as, in nulliparous women via maternal origin. Additional combinatorial events in the form of bacterial, viral, chemical or other types of challenge are suggestively necessary to activate microchimeric cells to result in lesions [22, 32]. Additionally, the observation that higher male microchimerism at the level of the MSY-linked ampliconic sequence, however, with lower ranges of transcript expressions in control, fertile patients compared to patients in other groups appears interesting.

Despite an apparent empirical confirmation in the form of qPCR and expression microarray data, the quantitative data obtained from RNA and DNA methods failed to show marked mutual congruencies in the present study, the basis of which was not explored. However, such lack of concordance has earlier been reported in other systems [54]. Moreover, such incongruences may arise from a lack of linear quantitative correspondence in the central flow from DNA to RNA in steady states, which may potentially play an important adjunct pathophysiological role in various diseases and conditions [55, 56]. The steady state data recorded in the present study can neither investigate this complex issue nor reveal the hierarchy of cause and effect relationship between male microchimerism and endometriosis or infertility. Further functional studies are required in order to gather large scale dynamic sets of data yielding knowledge in this regard, which may be of significance for understanding endometriosis and infertility.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first report with a general observation that several coding and non-coding genes of MSY origin displayed microchimerism in the form of presence of their respective DNA inserts along with their microarray-detectable expression. This expression was especially high in infertile women, and even higher in infertile patients with OE compared with fertile patients with and without endometriosis. Further chromosome-centric human proteomics and other functional studies are required to delineate how various routes of microchimerism indeed work in the pathophysiology of endometriosis and/or infertility.

References

Sengupta J, Anupa G, Bhat MA, Ghosh D. Molecular biology of endometriosis. In: Schatten H, editor. Human reproduction: updates and new horizons. Wiley: Blackwell Publishing; 2017. p. 71–116.

Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, Raj SG, Talbert LM. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64(2):151–4.

Brosens I, Brosens JJ, Benagiano G. The eutopic endometrium in endometriosis: are the changes of clinical significance? Reprod BioMed Online. 2012;24(5):496–502.

Nikoo S, Ebtekar M, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Shervin A, Bozorgmehr M, Vafaei S, et al. Menstrual blood-derived stromal stem cells from women with and without endometriosis reveal different phenotypic and functional characteristics. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20(9):905–18.

Ghosh D, Nagpal S, Bhat MA, Anupa G, Srivastava A, Sharma JB, et al. Gel-free proteomics reveals neoplastic potential in endometrium of infertile patients with stage IV ovarian endometriosis. J Reprod Health Med. 2015;1(2):83–95.

Gleicher N, El-Roeiy A, Confino E, Friberg J. Is endometriosis an autoimmune disease? Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70(1):115–22.

Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. Autoimmune and related diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(S1):S7–8.

Nielsen NM, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Rostgaard K, Frisch M. The co-occurrence of endometriosis with multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1555–9.

Adams Woldorf KM, Nelson JL. Autoimmune disease during pregnancy and the microchimerism legacy of pregnancy. Immunol Investig. 2008;37(5):631–44.

Case LK, Wall EH, Dragon JA, Saligrama N, Krementsova DN, Moussawi M, et al. The Y chromosome as a regulatory element shaping immune cell transcriptomes and susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Genome Res. 2013;23(9):1474–85.

Tiniakou E, Costenbader KH, Kriegel MA. Sex-specific environmental influences on the development of autoimmune diseases. Clin Immunol. 2013;149(2):182–91.

Arimoto T, Katagiri T, Oda K, Tsunoda T, Yasugi T, Osuga Y, et al. Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis of gene-expression profiles involved in ovarian endometriosis. Int J Oncol. 2003;22(3):551–60.

Khan MA, Sengupta J, Mittal S, Ghosh D. Genome-wide expressions in autologous eutopic and ectopic endometrium of fertile women with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:84.

Lebovic DI, Keeton K, Advincula AP. Evidence of fetal microchimerism in endometriosis. 9th world congress on endometriosis; Maastricht. Netherlands: Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123(S1):S27.

Fassbender A, Debiec-Rychter M, Van Bree R, Vermeesch JR, Mueleman C, Tomassetti C, et al. Lack of evidence that male fetal microchimerism is present in endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2015;22(9):1115–21.

Khan MA, Manna S, Malhotra N, Sengupta J, Ghosh D. Expressional regulation of genes linked to immunity & programmed development in human early placental villi. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(1):125–40.

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–78.

Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25.

Human Genome Assembly GRCh38.p12-Genome Reference Consortium. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/grc/human.

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):611–22.

Anupa G, Bhat MA, Srivastava AK, Sharma JB, Mehta N, Patil A, et al. Cationic antimicrobial peptide, magainin down-regulates secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by early placental cytotrophoblasts. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):121.

Sawaya HH, Jimenez SA, Artlett CM. Quantification of fetal microchimeric cells in clinically affected and unaffected skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(8):965–8.

Fitches AC, Yousem S, Cieply K, Stebbings S, Highton J, Hung NA. PCR detectable Y chromosome-specific DNA but no intact Y chromosome-bearing cells in polymyositis biopsies of two women with male offspring. Pathology. 2010;42(2):160–4.

Tvrdík D, Staněk L, Skálová H, Dundr P, Velenská Z, Povýšil C. Comparison of the IHC, FISH, SISH and qPCR methods for the molecular diagnosis of breast cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6(2):439–43.

Koudelakova V, Berkovcova J, Trojanec R, Vrbkova J, Radova L, Ehrmann J, et al. Evaluation of HER2 gene status in breast cancer samples with indeterminate fluorescence in situ hybridization by quantitative real-time PCR. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(4):446–55.

Uhlén M, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, Pontén F, Nielsen J. Transcriptomics resources of human tissues and organs. Mol Syst Biol. 2016;12(4):862.

Poverennaya EV, Shargunov AV, Ponomarenko EA, Lisitsa AV. The gene-centric content management system and its application for cognitive proteomics. Proteomes. 2018;6(1).

Zhong XY, Holzgreve W, Hahn S. Direct quantification of fetal cells in maternal blood by real-time PCR. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(9):850–4.

Rao L, Suryanarayana V, Kanakavalli M, Padmalatha V, Raseswari T, Pratibha N, et al. Short communication: Y chromosome microchimerism in female peripheral blood. Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;17(4):575–8.

Williams Z, Zepf D, Longtine J, Anchan R, Broadman B, Missmer SA, et al. Foreign fetal cells persist in the maternal circulation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2593–5.

Geck P. Symptotic detection of chimerism: Y does it matter? Chimerism. 2013;4(4):144–6.

Boddy AM, Fortunato A, Wilson Sayres M, Aktipis A. Fetal microchimerism and maternal health: a review and evolutionary analysis of cooperation and conflict beyond the womb. BioEssays. 2015;37(10):1106–18.

Guettier C, Sebagh M, Buard J, Feneux D, Ortin-Serrano M, Tricottet V, et al. Male cell microchimerism in normal and diseased female livers from fetal life to adulthood. Hepatology. 2005;42(1):35–43.

Chan WF, Atkins CJ, Naysmith D, van der Westhuizen N, Woo J, Nelson JL. Microchimerism in the rheumatoid nodules of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(2):380–8.

Rijnink EC, Penning ME, Wolterbeek R, Wilhelmus S, Zandbergen M, Duinen V, et al. Tissue microchimerism is increased during pregnancy: a human autopsy study. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015;21(11):857–64.

Yan Z, Lambert NC, Guthrie KA, Porter AJ, Loubiere LS, Medeleine MM, et al. Male microchimerism in women without sons: quantitative assessment and correlation with pregnancy history. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):899–906.

Bianchi DW, Zickwolf GK, Weil GJ, Sylvester S, DeMaria MA. Male fetal progenitor cells persist in maternal blood for as long as 27 years postpartum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(2):705–8.

O’Donoghue K, Chan J, de la Fuente J, Kennea N, Sandison A, Anderson JR, et al. Microchimerism in female bone marrow and bone decades after fetal mesenchymal stem-cell trafficking in pregnancy. Lancet. 2004;364(9429):179–82.

Khosrotehrani K, Reyes RR, Johnson KL, Freeman RB, Salomon RN, Peter I, et al. Fetal cells participate over time in the response to specific types of murine maternal hepatic injury. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):654–61.

Peterson SE, Nelson JL, Guthrie KA, Gadi VK, Aydelotte TM, Oyer DJ, Prager SW, Gammill HS. Prospective assessment of fetal-maternal cell transfer in miscarriage and pregnancy termination. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2607–12.

Nguyen Huu S, Oster M, Uzan S, Chareyre F, Aractingi S, Khosrotehrani K. Maternal neoangiogenesis during pregnancy partly derives from fetal endothelial progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(6):1871–6.

Nassar D, Droitcourt C, Mathieu-d'Argent E, Kim MJ, Khosrotehrani K, Aractingi S. Fetal progenitor cells naturally transferred through pregnancy participate in inflammation and angiogenesis during wound healing. FASEB J. 2012;26(1):149–57.

Sipos PI, Rens W, Schlecht H, Fan X, Wareing M, Hayward C, et al. Uterine vasculature remodeling in human pregnancy involves functional macrochimerism by endothelial colony forming cells of fetal origin. Stem Cells. 2013;31(7):1363–70.

Kamper-Jørgensen M, Hjalgrim H, Andersen AM, Gadi VK, Tjønneland A. Male microchimerism and survival among women. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):168–73.

Mahmood U, O'Donoghue K. Microchimeric fetal cells play a role in maternal wound healing after pregnancy. Chimerism. 2014;5(2):40–52.

Molina E, Chew GS, Myers SA, Clarence EM, Eales JM, Tomasewski M, et al. A novel Y-specific long non-coding RNA associated with cellular lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells and atherosclerosis-related genes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16710.

Sun J, Zhou M, Mao ZT, Hao DP, Wang ZZ, Li CX. Systematic analysis of genomic organization and structure of long non-coding RNAs in the human genome. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(7):976–82.

Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell. 2014;157(1):77–94.

Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152(6):1298–307.

Ørom UA, Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs usher in a new era in the biology of enhancers. Cell. 2013;154(6):1190–3.

Sun PR, Jia SZ, Lin H, Leng JH, Lang JH. Genome-wide profiling of long noncoding ribonucleic acid expression patterns in ovarian endometriosis by microarray. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):1038–46.

Wang Y, Li Y, Yang Z, Liu K, Wang D. Genome-wide microarray analysis of long non-coding RNAs in eutopic secretory endometrium with endometriosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37(6):2231–45.

Zhou C, Zhang T, Liu F, Zhou J, Ni X, Huo R, et al. The differential expression of mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs between ectopic and eutopic endometria provides new insights into adenomyosis. Mol BioSyst. 2016;12(2):362–70.

Nazarov PV, Muller A, Kaoma T, Nicot N, Maximo C, Birembaut, et al. RNA sequencing and transcriptome arrays analyses show opposing results for alternative splicing in patient derived samples. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):443.

Bader DM, Wilkening S, Lin G, Tekkedil MM, Dietrich K, Steinmetz LM, et al. Negative feedback buffers effects of regulatory variants. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11(1):785.

Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell. 2016;165(3):535–50.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patients who volunteered after understanding the goal of the proposed study.

Author details

MAB is PhD Student in the Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. JBS and KKR are Professors in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. JS is the Former Head and Professor, Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. DG is a Professor in Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Funding

The study was supported by projects granted by the Scientific and Engineering Research Board (SERB): SR/SO/HS/0119/2013 and EMR/2016/002255 from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. Expression microarray data are archived at NCBI GEO with accession number GSE120103.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAB carried out the experiments and data analysis, data interpretation and manuscript drafting. JBS and KKR carried out tissue collection and participated in data analysis. JS participated in designing the study, data analysis, data interpretation and manuscript drafting. DG conceived of the study, participated in its design, coordination, data analysis and interpretation and in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures described were reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and New Delhi. All procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of use of Human Subjects as per the Helsinki Declaration 2013 and Ethics committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and New Delhi, reference number IEC/NF-265/2013.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. List of genes and their primers used for quantitative PCR and qRT-PCR. (DOC 33 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. List of genes with their microarray expression levels from very low (− 3.5) to very high (5.0) in the different groups. (DOCX 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhat, M.A., Sharma, J.B., Roy, K.K. et al. Genomic evidence of Y chromosome microchimerism in the endometrium during endometriosis and in cases of infertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 17, 22 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0465-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0465-z