Abstract

Purpose

We investigated that preoperative membranous urethral length (MUL) would be associated with the recovery of urinary continence after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP).

Patients and methods

We studied 204 patients who underwent RALP between May 2013 and March 2016. All patients underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) preoperatively to measure MUL. Urinary continence was defined as the use of one pad or less (safety pad). The 204 patients were divided into two groups: continence group, those who achieved recovery of continence at 3, 6, and 12 months after RALP, and incontinence group, those who did not. We retrospectively analyzed the patients in terms of preoperative clinical factors including age, body mass index (BMI), estimated prostate volume, neurovascular bundle salvage, history of preoperative hormonal therapy, and MUL.

Results

The safety pad use rate was 69.6%, 86.9%, and 91.1% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. On univariate and multivariate analyses, MUL were significant factors in every term of recovery of urinary continence in both groups. According to the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, the preoperative MUL that could best predict early recovery of urinary continence at 3 months after RALP was 12 mm.

Conclusions

We suggest that preoperative MUL > 12 mm would be a predictor of early recovery of urinary continence after RALP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary incontinence is one of the most unfavorable complications influencing the quality of life for patients after radical prostatectomy (RP). In early 2000, the initial robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) was performed with the da Vinci surgical system [1]. Currently, RALP has become a more popular surgical procedure for RP in Japan. RALP is expected to achieve better outcomes regarding recovery of urinary continence than did the conventional procedure. Its advanced technology provides a three-dimensional operative view and laparoscopic instruments that mimic the movement of the human wrist. For the robotic approach, a meta-analysis of 51 studies showed statistically significant improvement in urinary continence recovery at 12 months with RALP compared to retropubic and laparoscopic RP [2].

Predictive factors for recovery of urinary continence after RP, such as patient age, body mass index (BMI), and prostate volume, have been reported [2, 3]. Membranous urethral length (MUL) as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also was reported to be a strong predictive factor for recovery of urinary continence in a systematic review and meta-analysis [4]. These reports demonstrated that preoperative MUL is associated significantly and positively with a return to continence following RP. However, few reports exist on the association of MUL and recovery of urinary continence after RALP in the Japanese population.

We evaluated the association of preoperative MUL with the recovery of urinary incontinence after RALP in Japanese patients.

Patients and methods

We performed RALP using the da Vinci Si surgical system in 204 consecutive patients from whom we could collect the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) questionnaire [5] at least preoperatively and 3 months after RALP between May 2013 and March 2016. All patients underwent pelvic MRI preoperatively. Most patients had no urinary incontinence before surgery; only ten patients had incontinence more than once a week. All surgical procedures were performed by four surgeons (YK, MK, RT, and WO). All surgeons are over 10 years as urologists, and each surgeon experienced RALP in more than 40 cases. RALP was performed via the conventional transperitoneal approach using the four-armed da Vinci surgical robot system [6]. In all cases, we performed the Rocco technique for posterior reconstruction of Denonvillier’s facia [7], anterior preservation [8], and bladder neck preservation [9] for preventing incontinence. Hemi–nerve sparing was performed depending on the cancer status [10]. Pelvic lymph node dissection also was performed in patients with a high risk of cancer according to the D’Amico criteria. We also offered all patients pelvic floor exercise education during the operative period.

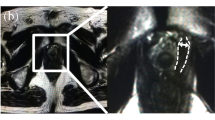

The MUL was measured by T2-weighted coronal and sagittal sections as a distance from the prostatic apex to the level of the urethra at the penile bulb on preoperative pelvic MRI (Fig 1) [11]. In terms of measuring the MUL, a number of urologists evaluated MUL of each case at the preoperative conference. Thereafter, the data of MUL was remeasured by a researcher.

Urinary continence was evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months after RALP using question 5 of the EPIC questionnaire [5]. Continence was defined as the use of one pad or less as a safety pad. We also examined the quality of life (QOL) score regarding urinary continence pre- and postoperatively using question 12 of the EPIC questionnaire [5].

The patients were divided into two groups: continence group, those who achieved recovery of urinary continence within 3, 6, 12 months, and incontinence group, those who did not.

Univariate analysis was performed with the t test, analysis of variance, chi-square, and Fisher’s exact test between continence and incontinence group regarding preoperative clinical factors including patient age, BMI, estimated prostate volume, clinical stage, neurovascular bundle salvage, history of preoperative hormonal therapy, positive surgical margin, leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis, and MUL. Multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model, and significances were tested using a likelihood ratio test. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For all statistical comparisons, differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Result

Mean patient age was 65 years, BMI was 23.7 kg/m2, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was 6.5 ng/ml, and MUL was 13.1 mm. Preoperative hormonal therapy was given in 34 (16.7%) patients, and hemi–nerve sparing was performed in 70 (34.6%; Table 1). The safety pad rate was 69.6%, 86.9%, and 91.1% at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively, and the pad-free rate was 33.8%, 49.7%, and 64.3%, respectively. The QOL regarding the urinary condition after RALP was worst at 3 months. It improved gradually, and at 1 year postoperatively, it had improved to the preoperative status (Fig. 2).

In the univariate analysis for recovery of urinary continence 3 months after RALP, patient age (P = 0.034), and MUL (P < 0.001) were statistically significantly associated with safety pad use. At 6 months after RALP, MUL (P = 0.004), console time, and leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis were statistically significant. At 12 months after RALP, MUL (P = 0.023) was statistically significant (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, patient age, leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis, and MUL achieved statistical significance with safety pad use. Among them, MUL was the most statistically significant with safety pad at 3 months after RALP (Table 3). Moreover, we estimated the optimal length of the MUL that could best classify between the continence and incontinence group. The cutoff point of MUL for recovery of urinary continence at 3 months after RALP was determined using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. We identified a reasonable cutoff point of MUL to be 12 mm (Fig. 3). MUL > 12 mm was a favorable predictor of recovery of urinary continence at 3 months after RALP. Furthermore, using the cutoff point of MUL 12 mm, our cases were classified into continence and incontinence groups with a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 70% (Fig. 3).

Discussion

RALP is expected to affect not only cancer control but also functional outcomes, such as continence and potency [12]. Especially, many reviews reported that patients who underwent RALP would tend to recover urinary continence within 1 year postoperatively earlier than patients who underwent retropubic RP (RRP) [12,13,14]. Early recovery of urinary continence is one of the strongest points of RALP. However, some patients suffer severe urinary incontinence after RALP. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate factors that influence recovery of urinary continence in patients undergoing RALP.

Several preoperative predictive factors for recovery of urinary continence after RALP, such as age, body mass index, prostate size, medical comorbidities, history of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), and history of preoperative urinary continence or lower urinary tract symptoms, were identified as studied previously. MUL based on preoperative imaging also is a predictive factor associated with urinary continence [15]. Coakley et al. [16] reported the first study using endorectal MRI to measure preoperative MUL and showed a correlation of MUL with urinary continence after RRP [13]. They demonstrated that a longer preoperative MUL was associated with a faster recovery of continence; at 1 year postoperatively, 120 of 134 patients (89%) with preoperative MUL > 12 mm were completely continent, compared to only 35 of 46 (76%) whose preoperative MUL was ≤ 12 mm. Despite the preoperative median length of MUL seems to be a minor difference among continence and incontinence groups in our study, in prior studies, an increase in MUL as low as 1 mm can increase the odds of return to continence up to 200% [17]. Our study demonstrated that preoperative MUL > 12 mm was the strongest factor indicating recovery of urinary continence 3 months after RALP. We identified 3 months after RALP as the early period for recovery of urinary continence because the result of QOL testing at 3 months after RALP was by no means satisfactory, and there still was room for improvement.

A previous study reported that MUL has anatomical variation [14]. Our study showed similar data as those reported in Korean patients [18, 19]. The average MUL in Asian patients may be approximately 12 mm. On the other hand, MUL in reports from the USA and Europe is slightly longer than that of Asians, but the racial difference is not clear because the number of reports is too small [15, 20].

MUL also has been associated with urinary continence recovery after RP [4, 15, 17,18,19]. Paparerl et al. [11] reported that a loss ratio of MUL between pre- and postoperatively was associated with postoperative incontinence. They suggested that preserving MUL is important for time-to-recovery and degree of recovery. The membranous urethra contains smooth muscle fibers along its entire length and is surrounded by the rhabdosphincter [21,22,23]. Decreasing intraoperative trauma when preserving the MUL, which includes a greater amount of smooth muscle fibers and rhabdosphincter, has an important role in continence after RP because it contributes to maintaining and increasing urethral closure pressure [24].

Our result suggested that a longer preoperative MUL has advantages for early urinary continence recovery after RALP. In the open era, MUL might not have been taken into account as an operator’s factor, but in the RALP era, the anatomical difference is evident more clearly and objectively. Therefore, not only the different operator technique, but also the MUL would relate directly to the early recovery of urinary continence.

In multivariate analysis, increasing patient age also was a risk factor for incontinence after RALP. Several studies showed a greater impact on urinary continence recovery with increasing age [25, 26]. Meanwhile, Basto et al. [27] reported urinary continence recovery rates after RALP in older men that were comparable to their younger counterparts, and thus, this should not be a reason to deny older men with a reasonable life-expectancy curative treatment for localized prostate cancer. In addition, leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis was one of the risk factors for incontinence after RALP in multivariate analysis. Leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis causes inflammatory change followed by fibrotic tissue development around the anastomotic site and sometimes causes a refractory fistula. Stavros et al. [28] reported leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis causes complications including incontinence after prostatectomy. When the MUL is < 12 mm, the patient is older or complication of leakage at vesicourethral anastomosis, early recovery of urination would not be easy. Therefore, we suggested that MUL is an important factor for preoperative informed consent regarding continence.

Our study has several limitations. First, there are some inherent limitations of pad use as an outcome measure. We defined continence as the use of one pad or less per day and did not measure pad weight. What is important in actual clinical situations is whether the number of pads is related to QOL improvement. Therefore, we investigated a QOL questionnaire for the use of a security pad. Second, MRI was performed before RALP, while MUL was measured retrospectively. In terms of measuring MUL, we evaluated MUL by a number of urologists at the preoperative conference. Therefore, the data of MUL which were summarized by a urologist who was blinded to clinical data would be more reproducible and for less selective bias in this study. Third, there was a negative impact between urinary continence and nerve sparing in our study. The aim of nerve preservation was not only for urinary continence but also for the prevention of erectile dysfunction. We also considered that cancer control was more important. Therefore, we have performed nerve preservation on one side where cancer was not detected. There was no case of bilateral nerve preservation. Although 70 cases were performed on nerve preservation, no significant difference in urinary incontinence rate between preservation group and no preservation group was shown (p = 0.312). Steineck et al. [10] reported that there is a relation between nerve preservation and urinary incontinence, but their study examined nerve preservation on both sides. In contrast, Pick et al. [29] reported no significant difference was found in continence rates after RALP between hemi–nerve sparing and no nerve sparing. We consider that a more detailed examination about an association between nerve sparing and urinary incontinence is necessary. Finally, the retrospective design also might be a limitation. We currently are performing a prospective examination of a modified procedure on the prostatic apex according to the MUL during RALP.

Conclusion

In conclusion, preoperative MUL > 12 mm would be a predictive factor for the recovery of urinary continence at 3 months after RALP. Evaluation of preoperative MUL would be useful in clinical settings because it is easy to measure and to acquire beneficial informed consent. This result should be validated by well-conducted prospective randomized controlled trials in the future.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- EPIC:

-

Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MUL:

-

Membranous urethral length

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RALP:

-

Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RP:

-

Radical prostatectomy

- TURP:

-

Transurethral resection of the prostate

References

Binder J, Kramer W. Robotically-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2001;87:408.

Bauer RM, Gozzi C, Hubner W, et al. Contemporary management of postprostatectomy incontinence. Eur Urol. 2011;59:985.

Sandhu JS, Eastham JA. Factors predicting early return of continence after radical prostatectomy. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:191.

Mungovan SF, Sandhu JS, Akin O, et al. Preoperative membranous urethral length measurement and continence recovery following radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):368.

Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandier HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899.

Yasui T, Tozawa K, Kurokawa S, et al. Impact of prostate weight on perioperative outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy with a posterior approach to the seminal vesicle. BMC Urol. 2014;14:6.

Rocco F, Carmignani L, Acquati P, et al. Restoration of posterior aspect of rhabdosphincter shorten continence time after retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2006;175:2201–6.

Hurtes X, Roupret M, Vaessen C, et al. Anterior suspension combined with posterior reconstruction during robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: results from a phase II randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2011;185:1262–7.

Freire MP, Weinberg AC, Lei Y, et al. Anatomic bladder neck preservation during robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: description of technique and outcomes. Eur Urol. 2009;56:972–80.

Steineck G, Bjartell A, Hugosson J, et al. Degree of preservation of the neurovascular bundles during radical prostatectomy and urinary continence 1 year after surgery. Eur Urol. 2015;67:559.

Paparel P, Akin O, Sandhu JS, et al. Recovery of urinary continence after radical prostatectomy: association with urethral length and urethral fibrosis measured by preoperative and postoperative endorectal magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Urol. 2009;55:629.

Di Pierro GB, Baumeister P, Stucki P, et al. A prospective trial comparing consecutive series of open retropubic and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in a centre with a limited caseload. Eur Urol. 2011;59(1):1.

Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:405.

Krambeck AE, DiMarco DS, Rangel LJ, et al. Radical prostatectomy for prostatic adenocarcinoma: a matched comparison of open retropubic and robot-assisted techniques. BJU Int. 2009;103(4):448.

Matsushita K, Kent MT, Vickers AJ, et al. Preoperative predictive model of recovery of urinary continence after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2015;116:577.

Coakley FV, Eberhardt S, Kattan MW, et al. Urinary continence after radical retropubic prostatectomy: relationship with membranous urethral length on preoperative endorectal magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2002;168:1032.

Lee H, Kim K, Hwang SI, et al. Impact of prostatic apical shape and protrusion on early recovery of continence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2014;84:844.

Jeong SJ, Yeon JS, Lee JK, et al. Development and validation of nomograms to predict the recovery of urinary continence after radical prostatectomy: comparisons between immediate, early, and late continence. World J Urol. 2014;32:437.

Son SJ, Lee SC, Jeong CW, et al. Comparison of continence recovery between robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy and open radical retropubic prostatectomy: a single surgeon experience. Korean J Urol. 2013;54(9):598.

Tienza A, Hevia M, Benito A, Pascual JI, Zudaire JJ, Robles JE. MRI factors to predict urinary incontinence after retropubic/laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:1343.

Strasser H, Ninkovic M, Hess M, Bartsch G, Stenzl A. Anatomic and functional studies of the male and female urethral sphincter. World J Urol. 2000;18:324.

Strasser H, Pinggera GM, Gozzi C, et al. Three-dimensional trans-rectal ultrasound of the male urethral rhabdosphincter. World J Urol. 2004;22:335.

Dalpiaz O, Mitterberger M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. Anatomical approach for surgery of the male posterior urethra. BJU Int. 2008;102:1448.

Bentzon DN, Graugaard-Jensen C, Borre M. Urethral pressure profile 6 months after radical prostatectomy may be diagnostic of sphincteric incontinence: preliminary data after 12 months’ follow-up. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:114.

Sacco E, Preyer-Galetti T, Pinto F, et al. Urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: influence by definition, risk factors and temporal trend in a large series with a long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2006;97:1234.

Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Rogers E, et al. Risk factors for urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 1996;156:1707.

Basto MY, Vidyasagar C, Marvelde L, et al. Early urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in older Australian men. BJU Int. 2014;114:29.

Tyritzis SI, Katafigiotis I, Constantinides CA, et al. All you need to know about urethrovesical anastomotic urinary leakage following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2012;188:369–76.

Pick DL, Osann K, Skarecky D, et al. The impact of cavernosal nerve preservation on continence after robotic radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011;108:1492–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DI contributed to the project development, data collection and management, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. YK contributed to the project development and manuscript editing. MK and RT contributed to the data analysis. AI, MO, RK, and TM contributed to the data collection. KI and WO contributed to the project development and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional research committee and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All the patients in this study gave informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikarashi, D., Kato, Y., Kanehira, M. et al. Appropriate preoperative membranous urethral length predicts recovery of urinary continence after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. World J Surg Onc 16, 224 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1523-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1523-2