Abstract

Background

It is not well clear how psychosocial factors like depressive symptoms, social support affect quality of life in rural elderly in China. This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of depressive symptoms in the association between social support and quality of life.

Methods

Cross-sectional data of 420 rural elderly were taken from four villages in Hangzhou City. They were interviewed with a demographic questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression, the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) for social support, and the short version of World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-BREF) for quality of life. Mediation was examined by a nonparametric Bootstrapping method, controlling for socioeconomic variables.

Results

Poor quality of life was associated with low social support and increased depressive symptoms. A significant indirect effect of social support existed through depression in relation to quality of life (ab = 0.0213, 95% CI [0.0071, 0.0421]), accounting for 9.5% of the effect of social support on quality of life. Approximately 4.8% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect of social support through depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms mediated the impact of social support on quality of life among rural older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There were approximately 150 million Chinese residents aged 65 years and above in 2017, accounting for 11.4% of China’s total population informed by National Bureau of Statistics in 2018 (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexeh.htm), and more than 70% of the aging population is distributed in rural areas [1]. As the population ages, the number of rural elderly populations will continue to increase due to the increasing life expectancy. The demographic transition presents challenges to health authorities, especially in terms of the increasing burden of disease and its negative effect on quality of life (QOL) of older adults. Increasing life expectancy without improving QOL directly influences health expenditures and has become a key public health issue in the more developed countries [2, 3]. It may also become a major burden to developing countries with high population densities and emerging economies, such as China and India. Actually in China, improving the QOL and physical and mental health of the elderly in rural areas is the basic guarantee for achieving the goal of healthy aging and active aging in China.

QOL is a multidimensional concept related to an individual’s satisfaction with various aspects of life, such as physical, psychological, social, environmental and general health perceptions. As indicated in some studies, QOL of older people in rural China is low [4, 5]. Older adults in countryside had poorer QOL and lower subjective well-being than the those live in town [6]. More than 16% of rural elderly people were still in poor health condition and about 12% often felt lonely and majority of them were lacking of entertainment activities [1]. QOL of elderly people is still poor and worry, especially continuing massive rural-to-urban migrations of mostly young adults and leaving more rural elderly in the village.

Social support has been recognized as a crucial role in improving QOL. It was identified four dimensions by Sherbourne and Stewart [7]: (1) emotional/ informational support (expression of positive affect, empathetic understanding, and encouragement of expressions of feelings/ offering of advice, information, guidance or feedback); (2) tangible support (provision of material aid or behavioral assistance); (3) positive social interaction (availability of other persons to do fun things with you); (4) affectionate support (involving expressions of love and affection). In the stress-buffering model, social support is supposed to increase an individual’s positive emotions to cushion the negative effects of stress [8, 9]. A number of studies have shown that social support has a positive impact on the QOL of elderly people [10,11,12]. Additionally, older people with sufficient social support tend to report higher life satisfaction score [13, 14] and psychological well-being [15]. There is no doubt that social support is benefit to QOL. However, the pathway how social support influences QOL in aging population is still unknown.

For aging people, depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders [16]. Several studies have indicated that depressive symptoms were important predictors of QOL in the elderly [12, 17,18,19]. QOL scores were low in the presence of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults [20] and the presence of minor symptoms of depression contributed the greatest amount of variance to the vast majority of QOL measures [21].

Depressed older people are more likely to have low social support as proven in earlier studies [12, 22,23,24]. A meta-analysis illustrated that older adults with more social support had lower prevalence of depression [25]. Lack of social support and feelings of loneliness are believed to be risk factors for depression in the elderly [26, 27] and perceived social support has been negatively associated with late-life depressive symptoms [28]. Also, living alone and decreased social participation and engagement reduce positive emotions of an older individual [29,30,31].

It seems plausible that depressive symptoms of older people are likely to account for poor QOL of older people with low social support. As Bekele et al. [32] proposed, a perceived lack of social support increases perceived threats of stressful events, and this leads to an increase in depressive symptoms and influences QOL ultimately. Social support is an important resource and the limited support of family and friends is one of the issues that affect the lives of older adults. Those who are living alone or empty-nest older adults are likely to be more vulnerable to depression [30, 33], and then have a worse QOL. The possible mediation effect of depressive symptoms on the association between social support and QOL enlightens us to give more attention to older adults with low social support.

Although the interactions between social support, depressive symptoms, and QOL have strong evidences, few of studies provide direct evidence for depressive symptoms as a pathway linking social support with QOL in rural Chinese older people. Thence, this study aims to clarify the direct and indirect effects of social support and depressive symptoms on QOL in Chinese rural elderly. We investigated the hypothesis that depressive symptoms mediates the influence of social support on QOL in rural elderly.

Methods

Setting and participants

As the depressive symptoms scores were designed to be measured as a mediator, the sample size was calculated according to the liner multiple regression. We performed a priori of power analysis by G*Power. Assuming α of 0.05, power of 0.95 (generally required largest sample size), effect size of 0.15 and with 2 tested predictors, the output parameters showed that the total sample size was 107. Because our research was also an assessment service for the local elderly and we expected as many older adults as possible can be evaluated, four villages were randomly selected as sample sites.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in a rural county of Hangzhou. We used a multistage sampling method. All of the 16 towns in the rural county were numbered in list, and then random sampling were conducted with the number of samples setting as two by the Excel’s sampling analysis. Then, 2 villages in each town were randomly selected in the same way. Participants were eligible to participate if they were (1) community-dwelling residents registered to the selected villages; (2) aged 60 years old and above; and (3) capacity to communicate independently with interviewers. In each village, 120 elderly adults registered in their electronic health records were randomly selected by the Excel’s sampling analysis to be invited to participate in this study. Written informed consent was provided by 429 participants, of whom nine had missing data on relevant measurements. The remaining 420 were included for analyses.

Measures

Depression

Depression was measured by the Chinese version of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which had been validated for use in the rural communities [34]. It is not just a screening tool for depression but also used to monitor the severity of depression [35]. The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.653.

Social support

Social support was assessed by the Chinese version of Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS (C)) [36], which was shown to display good reliability and validity for non-clinical samples [37]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.902 for the total scale and the values for Cronbach’s α were 0.719–0.776 for dimensions in this study.

Quality of life

QOL was assessed using the Chinese version of World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-BREF) [38, 39]. The instrument is composed of one item for general QOL (G1), one item for general health (G2) and 24 items from physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment domains. Domain scores were calculated by multiplying the mean of all item scores of each domain by a factor of 4 respectively, and potential scores for each domain ranged from 4 to 20 [40]. The overall QOL score is a total of four domains scores. The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.839.

Demographic variables

A brief self-report measure was used to collect background information, including age, gender, education, marital status, and economic satisfactory.

Because of the low education attainment in the aging population, the questionnaires including PHQ-9, MOS-SSS, and WHOQOL-BREF were dictated by well-trained study investigators to the participants. After finishing all the questionnaires, each participant received a gift as a token of appreciation. It took about 30–45 min per participant for the whole assessment. The research was approved by the institutional review boards of Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University and supported by the project “The Construction of the Psychological Environment for Home Care” of Department of Civil Affairs of Zhejiang Province (No. ZMZD201507).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency distributions) were conducted to show the demographic characteristics. A correlation matrix was calculated using partial correlation analysis for social support, depressive symptoms and QOL with demographic variables controlled. The mediating effect of depressive symptoms for social support and QOL was examined via a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure using the SPSS macro PROCESS (model 4) (http://www.afhayes.com) suggested by Hayes [41], which was not based on large-sample theory and made no assumptions about the shape of the distributions of the variables [42]. The number of bootstrap resamples was chosen to be 5000, under the bias corrected 95% confidence interval (CI).

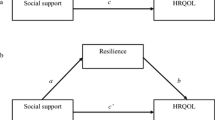

The mediation analysis by PROCESS was based on regression-based path analysis. Path coefficients (a, b, c, and c’) in the mediation model were obtained (see Fig. 1). The a-path represents the relationship between predictor (social support) and mediator variables (depression). The b-path indicates the association between the mediator (depression) and outcome variables (QOL) while the predictor variable (social support) is controlled. The c’-path (also called “direct effect”) shows the relationship between the predictor and outcome variables excluding the mediator variable, while c-path (also named “total effect”) including the mediator variable [43]. The mediation effect (c-c’ = ab, ab was also known as “indirect effect”) [44] is indicated by a statistically significant difference between c and c’. The indirect effect would be significant with CIs not including zero [42].

Actually, it can be said that none of the existing mediating effects can be satisfied, or that no single effect size can measure the size of mediating effects [45]. According to the recommendation of Wen and Fan [46], multiple statistics should be reported at the same time. We used percent mediation (PM, the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect) and R-squared mediation (R2med) [47] as measures of effect size. PM could be interpreted as the percent of the total effect accounted for by the indirect effect [48, 49]. Although it is unstable in several parameter combinations, and has excess bias in small sample sizes [47, 50], it is meaningful for a basic mediation model where the indirect effect ab and the direct effect c’ have the same sign, accompanied by the total effect and indirect effect in standardized form [45]. R2med means the variance of Y (QOL) can only be explained by X (social support) and M (depressive symptoms) together, but not by X or M independently. Fairchild, MacKinnon [47] proved that when the sample size is greater than 50, the value of R2med is stable and the deviation is small. The disadvantage of R2med is that there may be negative values in some cases [51, 52]. Then we repeated the earlier mediation analyses with different dimensions of social support to investigate whether mediation effects were showed in different dimensions of social support. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 22.0.

Results

Characteristics of elderly in rural China

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Correlations between social support, depression and quality of life

We examined correlations among variables for magnitude and plausibility with regard to our hypothesis (Table 2). Social support was correlated negatively with depressive symptoms and positively with QOL. QOL was negatively significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Mediation of depressive symptoms

The main results generated by SPSS macro PROCESS were presented in Table 3. Increased depressive symptoms were significantly associated with worse social support (β = − 0.0569; 95% CI: [− 0.0912, − 0.0226]) and QOL (β = − 0.3741; 95% CI: [− 0.4926, − 0.2555]). Social support significantly influenced QOL (β = 0.2232; 95% CI: [0.1797, 0.2667]), and this association were still significant after taking depressive symptoms into the model (β = 0.2232; 95% CI: [0.1797, 0.2667]).

There was a significant indirect effect on QOL by social support through depressive symptoms (ab = 0.0213; 95% CI [0.0071, 0.0421]), and the mediator accounted for approximately 9.5% of the total effect. The R2med value of 0.0479 was indicates that slightly less than 4.8% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect of social support through depressive symptoms. Applying Cohen’s [53] benchmark values for R2Δ (i.e., .02, .13, and 26), the effect size was in the small range.

Stratified analyses by different components of social support showed significant mediation effects. For emotional/informational support (ab = 0.0536; 95% CI [0.0059, 0.1154]), the mediator accounted for 7.9% of the total effect and approximately 3.5% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect. For tangible support (ab = 0.0449; 95% CI [0.0105, 0.0919]), the mediator accounted for 12.2% of the total effect and 3.4% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect. For positive social interaction (ab = 0.0859; 95% CI [0.0245, 0.1721]), the mediator accounted for 8.6% of the total effect and 3.9% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect. For affectionate support (ab = 0.1081; 95% CI [0.0403, 0.2080]), the mediator accounted for 9.7% of the total effect and 4.8% of the variance in QOL was attributable to the indirect effect.

These results revealed that depressive symptoms mediated the association between social support and QOL, which was consistent with the hypothesis. Different types of social support had different impacts on QOL.

Discussion

The study aimed to verify the mediating role of depressive symptoms in the relationship between social support and quality of life. Our results manifested that depressive symptoms mediated the association between social support and QOL in Chinese rural elderly. It provided evidences to support that social support may influence QOL through psychological factors. In our analyses, each aspect of social support had impact QOL, and the relationships were mediated by depressive symptoms.

To our knowledge, previous studies mostly focused on depression as a mediator between social support and QOL among patients with HIV/AIDS [32, 54]. However, sociodemographic and medical differences between the samples of HIV/AIDS patients and our sample limit direct migration of these results. The present study is the first attempt to investigate the association between social support and QOL with an emphasis on the mediating role of depressive symptoms in the Chinese aging population.

To explain these findings, the cognitive appraisal theory is a potential approach [55]. In this theory, cognitive appraisal processes include primary appraisal, in which one evaluates the situation’s potential for harm and benefit, and secondary appraisal, in which one assesses the situation’s controllability and one’s available coping resources. According to the theory, it can be posited that a lack of social support leads to negative psychological states such as anxiety or depression, because of a primary appraisal of stressors, in the case of multiple illnesses with aging, and a secondary appraisal of coping resources. Conversely, the perception of good social support could balance the harmful primary appraisal, resulting lower level of depression. In turn, these psychological states may ultimately influence QOL either through a direct effect on physiological processes that influence susceptibility to disease or through behavioral patterns that increase risk for disease [8].

The unique contribution of the study lies in the finding that depressive symptoms partially mediate the effect of social support on QOL among rural elderly. That is, rural older people with poor social support are at higher risk of developing depression, which contribute to poor QOL [12, 56] and higher risk of suicide [57, 58]. In this study, the variance in QOL explained by depressive symptoms was relatively small. We think the reason is that the prevalence of depression in the assessed population was not high. Only 15.7% suffered moderate and even severe depression (the cut-off score of PHQ-9 was 10). Additionally, the partial mediation of depressive symptoms indicates that other variables probably mediated the association between social support and QOL, such as resilience [59]. Nevertheless, we couldn’t neglect the mediation effect of depressive symptoms. Insufficient social support decreases the QOL of elderly people, and depression caused by social isolation worsens the QOL and increases disease torture and economic burden [60].

An implication of the mediation effect is the importance of identification and treatment of depression, given the high risk of developing depression in aging population especially those with low social support. As the previous studies have indicated that older people in rural areas are short of mental health services [61], which could result in failure to obtain timely and adequate diagnosis and treatment of depression for older people in rural areas. Prevention of depression could have a profound impact on QOL and well-being of rural elderly. Indeed, the prevalence rates of depression were up to 12.7% by DSM IV and ICD 10, and 2.2–20.2% by other clinically based methods [62], making it the second most common chronic disorder for the elderly. However, depression among older adults is under-recognized in Chinese culture [63], resulting in poor QOL [17], an exacerbation of preexisting medical conditions [64], an increase the risk of suicide [57] and dementia [65].

To deal with the challenges of increasing burden of mental disorders, it would be better to incorporate social support in interventions targeting or tailoring older people who always suffered by depression in rural China. There maybe two reasons. Firstly, social isolation may prevent older people from seeking and receiving social support [66], which may aggravate depression and reduce quality of life. Secondly, social support interventions can promote the treatment adherence [67], contributing to enhancing the subjective feeling of elderly, and alleviating their anxiety, depression, and physical discomforts and pains, thus improving their quality of life.

Given that all four dimensions of social support were indicated to be associated to QOL, those who would provide social support for elderly could be trained to take corresponding methods regarding these aspects in the future. For example, to provide informational support, the village doctors and other stakeholders could improve skills about communications with older adults regarding their physical and mental health. To provide emotional and affection support, the village doctors and other stakeholders were encouraged to be more patient and careful when listening to the older people. Additionally, regular community-based activities and weekly visits to those living alone could provide tangible support and positive social interaction.

Several studies have suggested that depression influences perceived social support and subsequently QOL [68, 69], while this study supported that social support has an impact on depressive symptoms and subsequently QOL. Some investigators have termed this bidirectional association of two independent variables as “moderation”. In this study, other factors addition to social isolation causing depression cannot be ruled out. It is possible that depression caused by other factors has decreased social activities and affected perceived social support, and the reduction in social support has exacerbated depression, which ultimately led to a decline in QOL. Thus, it still needs more evidence to clarify these relationships.

This study also has some other limitations. First, the findings may not be generalized to other settings because the sample is only from two towns in a rural county of Hangzhou, and the sample size is small. However, because both depression and poor social support are common issues around the world, our findings may still provide insights to prevent and intervene depression and improve QOL in a wide range of cultures. Second, depression was assessed without clinical diagnose. Nevertheless, the PHQ-9 is a valid and effective measure of depressive symptom severity, which is highly correlated with diagnosis of major affective illness by the cutoff of 10 or more. It’s necessary to conduct a more complete diagnostic assessment of depression in the further research, for depression is a clinical concept. Third, the lack of measurement of related factors like the comorbidities of chronic disease, diet, exercise, Activity of daily living, financial resources and other related factors were limitations in understanding the associations of interest. Chronic diseases and Activity of daily living were closely related to QOL in elderly. Future researches are recommended to include these factors for more robust evidence. Fourth, there was a partial mediation of depressive symptoms on the relationship between social support and QOL. Future research needs to clarify and integrate further variables in a model of social support and QOL among rural elderly people. Finally, this was a cross-sectional study that collected data at a single time point. Future researches are recommended to examine these associations in longitudinal studies.

Conclusions

Poor social support is significantly associated with the risk of depression and low QOL in rural elderly in China. Depressive symptoms significantly mediate the relationship between social support and QOL. These results suggest that social support is crucial to older adults’ health and QOL, and therefore it would be helpful for China’s rural elderly to incorporate social support in outpatient services afforded by village doctors or in community activities serviced by social workers.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- MOS-SSS:

-

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey

References

Shen S. Quality of life and old age social welfare system for the rural elderly in China. Ageing Int. 2012;37(3):285–99.

Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO global Oral health Programme. Community Dentistry Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):81–92.

Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Special Care Dentistry. 2008;28(6):224–36.

Liang Y, Wu W. Exploratory analysis of health-related quality of life among the empty-nest elderly in rural China: an empirical study in three economically developed cities in eastern China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):59.

Zhou B, et al. Quality of life and related factors in the older rural and urban Chinese populations in Zhejiang Province. J Appl Gerontol. 2011;30(2):199–225.

De-Ming LI, Chen TY. Quality of life and subjective well-being of the aged in Chinese countryside. Chin J Gerontol. 2007;27(12):1193–6.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57.

Sherbourne CD. The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(12):1393–400.

Cui L, Li H. A survey of city older adults’ social support network and the index of life satisfaction. Psychologicalence. 1997;2:1.

Li J. Social support and quality of life of the elderly in China. Popul Res. 2007;31(3):50–60.

Unalan D, et al. Coincidence of low social support and high depressive score on quality of life in elderly. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6(4):319–24.

Ho SC, et al. Life satisfaction and associated factors in older Hong Kong Chinese. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(3):252–5.

Ponce MSH. Predictors of quality of life in old age: a multivariate study in Chile. J Popul Ageing. 2011;4(3):121–39.

Bøen H. The importance of social support in the associations between psychological distress and somatic health problems and socio-economic factors among older adults living at home: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12(1):27.

Stoppe G. Depress Old Age. 2008;51(4):406.

Chan SW, et al. A cross-sectional study on the health related quality of life of depressed Chinese older people in Shanghai. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;21(9):883–9.

Gonzálezcelis AL, Gómezbenito J. Spirituality and quality of life and its effect on depression in older adults in Mexico. Psychology. 2013;4(3):178–82.

Dai J, Liu XH, Ma YG. Quality of life and its related factors on quality of life of aged people. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2002;10(4):246.

Gallegos-Carrillo K, et al. Role of depressive symptoms and comorbid chronic disease on health-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(2):0–135.

Brett CE, et al. Psychosocial factors and health as determinants of quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(3):505–16.

Lam BT, Cervantes AR, Lee WK. Late-life depression, social support, instrumental activities of daily living, and utilization of in-home and community-based Services in Older Adults. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2014;24(4):499–512.

Grav S, et al. Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2011;21(1–2):111–20.

Chi I, Chou K-L. Social support and depression among elderly Chinese people in Hong Kong. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2001;52(3):231–52.

Gariépy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallée A. Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(4):284–93.

Theeke LA, et al. Loneliness, depression, social support, and quality of life in older chronically ill Appalachians. Aust J Psychol. 2012;146(1–2):155–71.

Chao Y, Zhang N, Dong X. Association between perceived social support and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older Chinese Americans. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2018;4(suppl_1):439.

Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):175–84.

Gao LY, Wang M. Depression and general well-being of the elderly living alone and living with relatives. China J Health Psychol. 2014;22(1):56–8.

Min J, Ailshire J, Eileen C. Social engagement and depressive symptoms: do baseline depression status and type of social activities make a difference? Age Ageing. 2016;45(6):1–6.

Wang LF, Shi YJ. The investigation on psychological pressure of urban empty-nest elderly. Chin J Gerontol. 2008;28:1415–9.

Bekele T, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46.

Cheng P, et al. Disparities in prevalence and risk indicators of loneliness between rural empty nest and non-empty nest older adults in Chizhou, China. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;15:3.

Li Z, et al. Use of patient health Questionnaire-9(PHQ-9) among Chinese rural elderly. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2011;19(2):171–4.

Haddad M, et al. Detecting depression in patients with coronary heart disease: a diagnostic evaluation of the PHQ-9 and HADS-D in primary care, findings from the UPBEAT-UK study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78493.

Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(2):135–43.

Giangrasso B, Casale S. Psychometric properties of the medical outcome study social support survey with a general population sample of undergraduate students. Soc Indic Res. 2014;116(1):185–97.

Chien CW, et al. Development and validation of a WHOQOL-BREF Taiwanese audio player-assisted interview version for the elderly who use a spoken dialect. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(8):1375–81.

Chang Y, et al. Comprehensive comparison between empty Nest and non-empty Nest elderly: a cross-sectional study among rural populations in Northeast China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(9):857.

Chien C-W, et al. Agreement between the WHOQOL-BREF Chinese and Taiwanese versions in the elderly. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(2):164–9.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. xvii, 507-xvii, 507.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–31.

Funes CM, et al. Apathy mediates cognitive difficulties in geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(1):100–6.

MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivar Behav Res. 1995;30(1):41–62.

WEN Z, et al. Characteristics of an effect size and appropriateness of mediation effect size measures revisited. Acta Psychol Sin. 2016;48(4):435–43.

Wen Z, Fan X. Monotonicity of effect sizes: questioning kappa-squared as mediation effect size measure. Psychol Methods. 2015;20(2):193–203.

Fairchild AJ, et al. R2effect-size measures for mediation analysis. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(2):486–98.

Alwin DF, Hauser RM. The decomposition of effects in path analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 1975;40(1):37–47.

Wen ZL, Fan XT. Monotonicity of effect sizes: questioning kappa-squared as mediation effect size measure (vol 20, pg 193, 2015). Psychol Methods. 2015;20(2):193–203 II-II.

Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):593–614.

Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115.

Fairchild AJ, McQuillin SD. Evaluating mediation and moderation effects in school psychology: a presentation of methods and review of current practice. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48(1):53–84.

Cohen J. Statistical power ANALYSIS for the behavioral sciences. SERBIULA (sistema Librum 2.0). 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Huanguang J, et al. Health-related quality of life among men with HIV infection: effects of social support, coping, and depression. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18(10):594–603.

Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Tennen H. Health Psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):565–92.

Gurland B. The impact of depression on quality of life of the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8(2):377–86.

Sun WJ, et al. Depressive symptoms and suicide in 56,000 older Chinese: a Hong Kong cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(4):505–14.

Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. Bmj. 2011;343(7825):683–7.

Wu M, et al. Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders in nursing homes: the mediating role of resilience. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(3):783–92.

Zivin K, Wharton T, Rostant O. The economic, public health, and caregiver burden of late-life depression. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;36(4):631.

Ma Z, et al. Mental health Services in Rural China: a qualitative study of primary health care providers. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015(10):1–6.

Chen R, Copeland J. Epidemiology of Depression: prevalence and incidence; 2010.

Xie Z, et al. Development and validation of the geriatric depression inventory in Chinese culture. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(9):1505–11.

Schadewald RJ IV. The rate of depression and quality of life in a population age 60–99 years. Dissertations & Theses - Gradworks; 2010.

Tam CW, Lam LC. Association between late-onset depression and incident dementia in Chinese older persons. East Asian Arch Psychiatr. 2013;23(23):154–9.

Lv Y, Wu A, Li M. Psychosocial factors of depression in late life. Chin Ment Health J. 2004;18(4):254–3.

Li X, et al. Effectiveness of comprehensive social support interventions among elderly patients with tuberculosis in communities in China: a community-based trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(5):jech-2017–209458.

Hou W-L, et al. Mediating effects of social support on depression and quality of life among patients with HIV infection in Taiwan. AIDS Care. 2014;26(8):996–1003.

Kong L-N, et al. Social support as a mediator between depression and quality of life in Chinese community-dwelling older adults with chronic disease. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40(3):252–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research assistants in Tonglu and Jiande County for their assistance in data collection. We also thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by Department of Civil Affairs of Zhejiang Province (No.ZMZD201507).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayu Wang and Shulin Chen contributed to the conception of the study; Jiang Xue contributed significantly to analysis and manuscript preparation; Jiayu Wang and Jiang Xue performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; Yuxing Jiang and Tingfei Zhu helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was given ethical approval by the Institutional Review Boards of Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University. All participants gave their consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Xue, J., Jiang, Y. et al. Mediating effects of depressive symptoms on social support and quality of life among rural older Chinese. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 242 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01490-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01490-1