Abstract

Background

Parasite infections stimulate total and specific IgE production that, in the case of Toxocara canis infection, corresponds to chronic allergic symptoms. There may also be other infections which have similar symptoms, such as Ascaris lumbricoides infection. Ascaris lumbricoides is a large nematode that causes abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, anorexia and intermittent diarrhoea. Patients with ascaridiasis and high IgE levels may also have allergy-like symptoms such as asthma, urticaria and atopic dermatitis.

Case presentation

We report a case of atopic dermatitis caused by Ascaris lumbricoides which shows the important role of parasitic infection in patients with long-lasting dermatitis. The patient was a 12-year old female suffering since early infancy from atopic dermatitis and asthma. She was treated for dermatitis with oral bethametasone and topical pimecrolimus with little benefit. After two cycles of mebendazole therapy, the patient showed progressive improvement of symptoms.

Conclusions

In patients with dermatitis, Ascaris lumbricoides infection should be not excluded: adequate anthelmintic treatment may result in complete regression from the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In western countries, it is well known that allergic disease prevalence is increasing: this regards respiratory, cutaneous and food allergies [1]. Genetic predisposition, the interaction between genome and environment and the so-called hygiene hypothesis are the mechanisms that seem to be involved. Nevertheless, other aspects need to be studied in depth; one of these is the role of IgE title and factors that can determine its increase. Helminth infections can stimulate total and specific IgE production. It has been described that Toxocara canis can induce chronic allergic symptoms [2] and it is thought that other helminth infections can act similarly as a trigger or can maintain an inflammatory status. There is growing international interest in the study of the relationship between helminth infections and allergic diseases. Ascaridiasis is a common intestinal infestation caused by nematodes of the genus ascaridia. Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the main common causes of human parasitic infection. Patients with ascaridiasis are generally asymptomatic and may present with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, anorexia and intermittent diarrhoea [3]. Patients with ascaridiasis and high IgE levels may have allergy-like symptoms such as asthma, urticaria and atopic dermatitis. This study was aimed at evaluating changes in total and Ascaris-specific IgE levels, as well as in symptoms, following anti-helminthic therapy in patients with atopic dermatitis resistant to standard anti-allergic treatment.

Case report

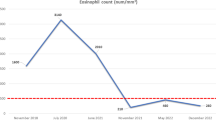

The patient was a 12-year old female suffering since early infancy from atopic dermatitis and asthma. Both skin and respiratory symptoms were perennial, with worsening in spring and autumn. Allergy testing, performed at the age of 18 months, resulted positive to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and farinae. In addition, tomato, hen’s egg and cow milk were positive to skin prick tests. Following environmental measures to reduce house dust mite exposure and the elimination of tomato, egg and milk from the diet, there was an improvement of the patient’s asthma condition but not in atopic dermatitis. At 3 and 6 years of age, there was a worsening of dermatitis with modest response to topical corticosteroids, while asthma was no longer present. A further worsening of atopic dermatitis occurred at 9 years of age, which was treated with oral bethametasone and topical pimecrolimus. In September 2014, the patient was referred to our Unit; we found peripheral eosinophilia of 14.4% and, suspecting parasitic infections, we evaluated specific IgE for A. lumbricoides, which had a value of 32.50 kU/L. Anthelmintic therapy was prescribed using mebendazole (one 100 mg 1 tablet b.i.d. for 3 days), repeated after 20 and 50 days. Table 1 shows patient data. One month after the first two cycles of therapy, the patient showed progressive improvement of symptoms (Fig. 1), and eosinophilia was 12%. Six months after the end of therapy, the skin was free from dermatitis and a further decrease was observed for eosinophilia (11.20%) and Ascaris-specific IgE (23.90 kU/L).

Conclusions

The hygiene hypothesis assumes the presence of an inverse relationship between infections during childhood and the development of atopic disorders that is accompanied by a shift from Th2 response to a Th1 response [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Clinical and epidemiologic studies have shown that the increasing prevalence of allergic disorders such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, eczema and allergic conjunctivitis has an inverse relationship to parasitic infection [10,11,12,13,14]. In several helminthic diseases, IgE is involved in protection of the host against the parasitic agent, consistent with the hypothesis that parasitic infection competes for the IgE-Th2 lymphocyte–eosinophil response [15]. A study highlighted the concept that common domains may exist between species that stimulate the Th2 pathway response (parasites and common allergens), examining some common conserved domains (amino acid sequences) [16]. Thus, helminths are modulators of the host immune system, and infections with these parasites have been associated with protection against allergies and autoimmune disease [17]. However, another study observed a positive association between number of helminth infections and peripheral blood eosinophilia, elevated total IgE, spontaneous production of IL-10 and helminth antigen-stimulated production of Th2 cytokines [18]. An increasing number of helminth infections induces a dose–response effect on allergic inflammatory markers and thus allows us to link these infections to allergic diseases, such as atopic dermatitis. Moreover, the study cited above shows the role of helminth infections on Th2 immune response (e.g. the production of Th2 cytokines by peripheral blood leukocytes stimulated with helminth antigens and the peripheral blood eosinophilia) and on the increase in stimulated IL-10 production which could play a role in the suppression of immediate hypersensitivity reactions in the skin. The present case shows that the role of infection from A. lumbricoides in patients with long-lasting dermatitis should not be overlooked. Suitable anti-helminthic treatment may result in complete recovery from the disease. Further studies are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms by which this immune modulation occurs, to explain the complex relationship between ascariasis and susceptibility to childhood atopic dermatitis.

References

Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–43.

Qualizza R, Incorvaia C, Grande R, Makri E, Allegra L. Seroprevalence of IgG anti-Toxocara species antibodies in a population of patients with suspected allergy. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:783–7.

de Lima Corvino D, Bhimji S. Ascariasis. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

Lynch NR, Hagel I, Perez M, Di Prisco MC, Lopez R, Alvarez N. Effect of anthelmintic treatment on the allergic reactivity of children in a tropical slum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:404–11.

Mitre E, Norwood S, Nutman TB. Saturation of immunoglobulin E (IgE) binding sites by polyclonal IgE does not explain the protective effect of helminth infections against atopy. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4106–11.

Wilson MS, Maizels RM. Regulation of allergy and autoimmunity in helminth infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;26:35–50.

Correale J, Farez MF. The impact of environmental infections (parasites) on MS activity. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1162–9.

Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9.

Pontes-de-Carvalho L, Mengel J, Figueiredo CA, Social Changes, Asthma and Allergy in Latin America (SCAALA)’s Study Group, Alcantara-Neves NM. Antigen mimicry between infectious agents and self or environmental antigens may lead to long-term regulation of inflammation. Front Immunol. 2013;4:314.

Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, Góes AM, Oliveira RR, Pacífico LG, et al. Schistosoma mansoni antigens modulate the allergic response in a murine model of ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:266–74.

Tang L, Chen Y, Wang L, Zhang S, Zeng X, Yi X. Identification and characterization of peptides mimicking the epitopes of metalloprotease of Schistosoma japonicum. Cell Mol Immunol. 2005;2:219–23.

Santiago HC, LeeVan E, Bennuru S, Ribeiro-Gomes F, Mueller E, Wilson M, et al. Molecular mimicry between cockroach and helminth glutathione S-transferases promotes cross-reactivity and cross-sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(248–56):e9.

Santos AB, Rocha GM, Oliver C, Ferriani VP, Lima RC, Palma MS, et al. Cross- reactive IgE antibody responses to tropomyosins from Ascaris lumbricoides and cockroach. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(1040–6):e1.

Santiago HC, Bennuru S, Boyd A, Eberhard M, Nutman TB. Structural and immunologic cross-reactivity among filarial and mite tropomyosin: implications for the hygiene hypothesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:479–86.

Santiago HC, Bennuru S, Ribeiro JM, Nutman TB. Structural differences between human proteins and aero- and microbial allergens define allergenicity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40552.

Rottem M, Geller-Bernstein C, Shoenfeld Y. Atopy and asthma in migrants: the function of parasites. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;167:41–6.

Cooper PJ, Barreto ML, Rodrigues LC. Human allergy and geohelminth infections: a review of the literature and a proposed conceptual model to guide the investigation of possible causal associations. Br Med Bull. 2006;79–80:203–18.

Alcântara-Neves NM, de S G Britto G, Veiga RV, Figueiredo CA, Fiaccone RL, da Conceição JS, et al. Effects of helminth co-infections on atopy, asthma and cytokine production in children living in a poor urban area in Latin America. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:817.

Authors’ contributions

RQ visited and treated the patient and wrote the paper; LML wrote the paper; FF wrote the draft paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Informed consent to clinical data collection and publication was obtained from the patient.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable in this retrospective clinical study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qualizza, R., Losappio, L.M. & Furci, F. A case of atopic dermatitis caused by Ascaris lumbricoides infection. Clin Mol Allergy 16, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12948-018-0088-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12948-018-0088-5