Abstract

Background

To evaluate the characteristics of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) patients with or without chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Germany.

Methods

Using combined DPV/DIVE registry data, the analysis included patients with T2DM at least ≥ 18 years old who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value available. CKD was defined as an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria (≥ 30 mg/g). Median values of the most recent treatment year per patient are reported.

Results

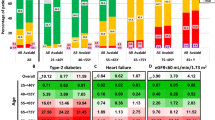

Among 343,675 patients with T2DM 171,930 had CKD. Patients with CKD had a median eGFR of 48.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 51.2% had a urinary albumin level ≥ 30 mg/g. They were older, had a longer diabetes duration and a higher proportion was females compared to patients without CKD (all p < 0.001). More than half of CKD patients (53.5%) were receiving long-acting insulin-based therapy versus around 39.1% of those without (p < 0.001). CKD patients also had a higher rate of hypertension (79.4% vs 72.0%; p < 0.001). The most common antihypertensive drugs among CKD patients were renin-angiotensin-aldosteron system inhibitors (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors 33.8%, angiotensin receptor blockers 14.2%) and diuretics (40.2%). CKD patients had a higher rate of dyslipidemia (88.4% vs 86.3%) with higher triglyceride levels (157.9 vs 151.0 mg/dL) and lower HDL-C levels (men: 40.0 vs 42.0 mg/dL; women: 46.4 vs 50.0 mg/dL) (all p < 0.001) and a higher rate of hyperkalemia (> 5.5 mmol/L: 3.7% vs. 1.0%). Comorbidities were more common among CKD patients (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The results illustrate the prevalence and morbidity burden associated with diabetic kidney disease in patients with T2DM in Germany. The data call for more attention to the presence of chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes, should trigger intensified risk factor control up and beyond the control of blood glucose and HbA1c in these patients. They may also serve as a trigger for future investigations into this patient population asking for new treatment options to be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has increased in recent decades alongside an increase in diabetes and hypertension, the main drivers of CKD [1]. Kidney disease attributable to diabetes mellitus (diabetic kidney disease; DKD) is one of the most common complications of diabetes and affects approximately 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [2, 3]. It can ultimately lead to end-stage renal disease and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and death [4,5,6]. Moreover, people with diabetes can also develop CKD due to etiologies other than diabetes and some may have a combination of DKD and non-diabetic CKD [7]. The prevalence of T2DM is increasing worldwide [8, 9] and consequently diabetes-associated CKD is a major contributor to the global burden of disease [4].

The prevalence of diabetes and CKD and associated healthcare costs vary between different regions of the world [2, 8, 10], and it is therefore important to understand the epidemiology of diabetes-associated CKD and patient characteristics within specific regions and/or countries. In Germany it is estimated that up to 10% of people have been diagnosed with T2DM [11,12,13,14] and approximately 40% of individuals with T2DM have comorbid CKD [15].

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the epidemiology of T2DM-associated CKD in Germany and compare the characteristics of patients with or without CKD, using data from the Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdokumentation (DPV) and DIabetes Versorgungs-Evaluation (DIVE) registries.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This analysis used combined data from the DPV and DIVE registries [16,17,18,19]. Their design has been described previously. In short, the DPV initiative collects data on patients with diabetes mellitus from centers predominantly in Germany and Austria [18,19,20]. Data are collected every 6 months using DPV software and the anonymized data are sent to the University of Ulm for aggregation into the database. The DPV initiative, which was established in 1995, was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Ulm, and data collection was approved by local review boards.

The DIVE registry was established in Germany in 2011 [16, 17, 21]. Consecutive patients with diabetes mellitus, regardless of their disease stage, were enrolled from centers across the country, and continue to be followed up. Data are entered into an online database using DIAMAX (Axaris, Ulm, Germany) or DPV software. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School of Hannover, and all patients included in the DIVE registry provided written informed consent.

A total of 394 centers were included in the present analysis (382 Germany, 11 Austria, 1 Luxemburg). Patients were sampled in March 2018 (DPV) and May 2018 (DIVE). and included in the current analysis if they had type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), were at least 18 years old, registered between 2000 and 2017 and had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value calculated according to the modification of diet in renal disease formula (MDRD) available.

Documentation

For the current analysis, data regarding age, gender, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, dyslipidemia, type of healthcare provider (office-based/hospital-based), renal parameters, antidiabetic and antihypertensive drug treatment and current comorbidities were collected. For each patient data of the most recent treatment year in the period 2000–2017 was aggregated (median 2013) and analyzed. CKD was defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria (≥ 30 mg/g) [22, 23]. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure (BP) levels above 140 mmHg systolic (SBP) or 90 mmHg diastolic (DBP) or receiving antihypertensive drugs. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL and/or LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dL and/or HDL-C < 40 mg/dL and/or triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or receiving lipid-lowering drugs. Coronary artery disease was defined as prior myocardial infarction or angina pectoris.

eGFR was calculated according to the MDRD formula: 175 × creatinine [mg/dL] − 1.154 × age [years] − 0.203 × 0.742 [if female] [24].

Statistics

Data from all patients were combined and analyzed as a single data set. Categorical variables are presented as percentages. Continuous variables are presented as medians with first and third quartiles (Q1, Q3). T2DM patients with CKD were compared to T2DM patients without CKD. Unadjusted comparisons were conducted using a Chi squared or Kruskal–Wallis test. The false discovery rate method was used to correct p-values for multiple testing. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We also conducted analyses stratified by comorbidity. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

The analysis population comprised 343,675 patients with T2DM, aged ≥ 18 years, for whom data to compute the GFR-MDRD value were available (Fig. 1), of whom 171,930 had CKD and 171,745 did not have CKD. A total of 108,366 patients were classified as being at low risk, 64,773 patients at moderate risk, 36,117 patients at high and 31,254 patients at very high risk (Fig. 2).

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease by GFR and albuminuria (based on [22]). Green, low risk (if no other markers of kidney disease, no CKD); yellow, moderately increased risk; orange, high risk; red, very high risk. *240.510 patients with information on eGFR category and albuminuria, data are presented as absolute numbers (percent of 240.510). n = 103.165 with missing values on microalbuminuria and/or macroalbuminuria

General characteristics

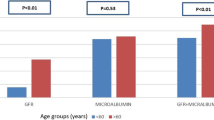

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1 for the overall study population and for patients with or without CKD. T2DM patients with CKD were more likely than those without CKD to be treated by a hospital-based physician (68.5% vs 59.7%, p < 0.001), were older than those without CKD (median 74.5 vs 65.5 years, p < 0.001), had a longer median duration of diabetes (10.3 vs 7.2 years, p < 0.001), and were more likely to be female (52.4% vs 42.0%, p < 0.001).

Patients with CKD had a higher rate of hypertension (79.4% vs 72.0%, p < 0.001), they were more likely to be receiving antihypertensive drugs (62.6% vs 20.7%, p < 0.001) and their median BP value was (slightly) lower than those for patients without CKD (Table 1). Both groups had evidence of high levels of diabetic dyslipidemia, with elevated triglyceride levels and low HDL-C levels; median values were significantly worse in patients with CKD than in those without CKD (triglycerides: 157.9 vs 151.0 mg/dL; HDL-C in men: 40.0 vs 42.0 mg/dL; HDL-C in women: 46.4 vs 50.0 mg/dL; both p < 0.001). As would be expected, patients with CKD had significantly worse values for parameters reflecting kidney function/damage than those without CKD. The rate of hyperkalemia (> 5.5 mmol/L) was 3.7% versus 1.0% (p < 0.001).

Patient characteristics for the whole study population (i.e. irrespective of CKD status) stratified by region of Germany (north, south, west, east) are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Drug treatment

Antidiabetic and antihypertensive drug treatments received by T2DM patients with or without CKD are summarized in Table 2. With respect to antidiabetic treatment, patients with CKD were more likely than those without CKD to be prescribed glinides (3.9% vs 3.0%, p < 0.001) and insulin (short-acting insulin: 51.4% vs 36.7%; long-acting insulin 53.5% vs 39.1%; both p < 0.001). All other drug classes were more common in those without CKD, most notably metformin (28.6% vs 47.2%). Patients with CKD were less likely than those without CKD to be receiving ≥ 2 antidiabetic drugs (15.0% vs 21.0%, p < 0.001).

Consistent with the higher rate of hypertension seen among T2DM patients with CKD, patients with CKD were more likely than those without CKD to be receiving antihypertensive drugs (p < 0.001 for all classes) and to be receiving ≥ 2 drugs (49.2% vs 33.6%, p < 0.001). The most common antihypertensive drugs prescribed to patients with CKD were renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers (comprising angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors 33.8% and angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs] 14.2%), followed by diuretics (40.2%) and beta-blockers (36.7%). The most common drugs among patients without CKD were also RAAS blockers (comprising ACE inhibitors 28.6% and ARBs 10.3%), followed by beta-blockers (25.8%) and diuretics (23.1%).

Comorbidities

The rates of all comorbidities—stroke, retinopathy, coronary artery disease (including myocardial infarction), peripheral artery disease and diabetic foot complications (including amputations)—were significantly higher among T2DM patients with CKD compared to those without CKD (all p < 0.001); Table 3.

Patient characteristics stratified by comorbidity for the overall study population are summarized in Table 4. The majority of patients with comorbidities were being treated by hospital-based physicians, with the highest rates seen for patients with prior stroke (74.7%) CAD (69.5%) or CKD (68.5%). The proportion of female patients was highest for patients with CKD (52.4% vs 36.4–46.2% for other comorbidities). Median duration of diabetes was slightly shorter in those with stroke, CAD or CKD (10.3–10.6 years) than in those with peripheral artery disease, foot complications or retinopathy (12.0–16.1 years). The rates of hypertension and antihypertensive drug treatment were slightly lower for patients with diabetic foot complications (hypertension 79.5%; treatment 64.0%) and CKD (hypertension 79.4%; treatment 62.6%) than for patients with other comorbidities (hypertension 82.5–85.3%; treatment 70.0–75.4%). Median triglyceride level was higher in those with CKD compared with those with other comorbidities (157.9 vs 148.9–152.0 mg/dL).

Drug treatment stratified by comorbidity for the overall study population is summarized in Additional file 2: Table S2. The most noticeable differences between patients with CKD and those with other comorbidities were a lower rate of metformin use (28.6% vs 30.8–32.5%) and lower rate of use of ≥ 2 antidiabetic drugs in those with CKD or retinopathy (15.0% vs 15.6–17.6%).

Discussion

Diabetes is the leading cause of CKD worldwide, and despite the use of current antidiabetic and antihypertensive therapies, the risk remains high [4]. The presence of CKD makes a substantial contribution to the socioeconomic burden associated with diabetes [25, 26].

Estimates of the prevalence of T2DM in Germany range from 5 to 10% depending on the diagnostic criteria used [11, 12, 14, 27] and it is projected to increase to 16% by 2040 among people aged ≥ 40 years [14]. According to the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2008–2011 (DEGS1), the prevalence of comorbid CKD among adults with T2DM in Germany is approximately 40% [15], which is in line with global estimates [4]. DEGS1 also showed that 2.3% of the adult population of Germany (i.e. more than 2 million people) has at least moderate impairment of renal function (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and the prevalence was 2.25-fold higher among people with diabetes compared with those without diabetes [28]. Analysis of the German Chronic Kidney Disease (GCKD) cohort indicated that 35% of patients with moderate CKD who are under specialist care in Germany have diabetes, and that diabetic nephropathy is considered the leading cause of kidney disease in 41% of that subgroup of patients [29]. People with diabetes can develop CKD not only as a consequence of their diabetes, but also due to other etiologies, and can have a combination of diabetic kidney disease and non-diabetic CKD [7].

The current study analyzed DPV/DIVE data for 343,675 adults with T2DM who had a GFR-MDRD value available and found a prevalence of CKD of 50.0%, which is higher compared with previous estimates [15]. Among T2DM patients with CKD included in the study, median eGFR was 48.9 mL/min/1.73 m2, 51.2% had micro or macroalbuminuria and 3.7% had hyperkalemia (> 5.5 mmol/L) vs 1% in the T2DM population without CKD. As reflected in Fig. 2 of the present paper, the majority of patients (n = 94,412) had their diagnosis being made based on an eGFR < 60 mg/min/1.73 m2 only. Further 37,732 had albuminuria ≥ 30 mg/g while having an eGFR ≥ 60 mg/min/1.73 m2, and 33,388 patients had their diagnosis made based on the presence of microalbuminuria alone. Further markers for the identification of patients with chronic kidney disease in the presence of diabetes as well as the identification of those with diabetic kidney disease would be of interest, such as plasma copeptin [30] and prognostics markers such as symmetric and asymmetric dimethylarginine [31], but these were not contained in the present dataset.

The study compared the characteristics of T2DM patients with and without CKD. T2DM patients with CKD were significantly older, had a longer duration of diabetes and were more likely to be female than those without CKD. Older age is a recognized risk factor for CKD [2, 4]. CKD is generally considered to be more common among men than women [2, 4], although the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) identified female sex as a risk factor for impaired renal function [32]. While weight was slightly higher among patients with CKD in our study, there was no association of BMI with the level of CKD as suggested by prior research [33]. The current study also found that in Germany, T2DM patients with CKD were significantly more likely than those without CKD to be under the care of a hospital-based physician.

Based on median HbA1c values, the overall level of glycemic control appeared to be generally acceptable, and comparable among patients with CKD compared with those without CKD (median 7.2 vs. 7.1%, p < 0.001). This is important as HbA1c trajectories have been associated with renal disease progression [34]. Although a wide range of antidiabetic medications were prescribed to patients in both the CKD and non-CKD groups, it was notable that more than 50% of the patients with CKD were receiving long-acting insulins compared with < 40% of those without CKD. It has been reported elsewhere that only 31% of a general German T2DM population were prescribed insulin-based therapies [13]. The findings of the current study are consistent with an analysis of the GCKD cohort, which also found that while antidiabetic treatment patterns for T2DM patients with CKD varied, more than 50% were receiving insulin-based therapies [35]. Similar to the current study, overall metabolic control appeared satisfactory in the GCKD cohort, with the median HbA1c value being 7.0% [35]; however, it was found that use of insulin was associated with an increased HbA1c value > 7.0% [35].

In patients with T2DM, hypertension increases the risk of albuminuria, impaired renal function, end-stage renal disease and death [32, 36, 37]. A diagnosis of hypertension was common in the T2DM population enrolled in the current study and was significantly more frequent among those with CKD than among those without CKD. However, median BP values were lower in patients with CKD, presumably because they were more likely to be receiving antihypertensive medication. The most common classes of antihypertensive drugs prescribed to T2DM patients with CKD were RAAS blockers (ACE inhibitors 33.8%, angiotensin receptor blockers 14.2%), diuretics (40.2%) and beta-blockers (36.7%).

RAAS blockade is recommended for diabetic patients with hypertension, including those with CKD [38]. Treatment with either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB reduces the progression of CKD in patients with macroalbuminuria; however, combining these two drug classes provides no additional benefit in terms of outcomes and increases the risk of adverse events [39,40,41]. Adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) to an RAAS blocker reduces proteinuria further in patients with CKD [42, 43], but steroidal MRAs are associated with adverse effects, including an increased risk of hyperkalemia [44]. There is no information about the use of MRA in this analysis, as MRA are documented as diuretics only without further specification.

Dyslipidemia affects at least 75% of patients with T2DM [45] and lipid levels are generally worse in T2DM patients with CKD compared with those without CKD [46]. The results of the current study are consistent with this: more than 85% of patients in both groups had dyslipidemia, but median triglyceride and HDL-C levels were significantly worse in those with CKD than those without CKD.

Diabetes is associated with both microvascular complications (nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (including atherosclerotic disorders and impaired cardiac function) [47]. Both diabetes and CKD are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and the risk is particularly high in patients who have CKD [48]. CKD also increases the risk of mortality compared with T2DM patients without kidney disease [48, 49]. In the current study, comorbidities, including stroke, coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease, as well as retinopathy and diabetic foot complications were significantly more common in T2DM patients with CKD compared to those without CKD.

Statistical comparison of the characteristics of patients with different comorbidities was not undertaken, but when stratified by comorbidity, there was a greater proportion of female patients and a higher median triglyceride level in the CKD subgroup compared with other comorbidity subgroups. Patients with CKD or prior stroke were most likely to be treated by a hospital-based physician. Median duration of diabetes was slightly shorter in patients with CKD, stroke or CAD compared with those with peripheral artery disease, foot complications or retinopathy. Hypertension and antihypertensive treatment appeared to be less common among patients with CKD or diabetic foot complications compared with those with other comorbidities. The rates of metformin use and use of ≥ 2 antidiabetic drugs were lower in the CKD subgroup compared with other comorbidity subgroups, while the rate of antihypertensive drug use was lower among patients with CKD or diabetic foot complications compared with those with other comorbidities.

Regional differences in the prevalence and characteristics of patients with T2DM have been noted in Germany, which are thought to relate to differences in the distribution of risk factors, regional deprivation and individual socioeconomic status [12, 27, 50]. The current study included a comparison of the characteristics of the overall T2DM study population (irrespective of their CKD status) between different regions of Germany. Statistical comparisons were not performed, but some potentially interesting differences were noted. Although patients in the eastern region were most likely to be treated by a hospital-based physician, this region had the lowest rate of attainment of HbA1c < 7.0% (closely followed by the north). T2DM patients in the eastern region also had the lowest median eGFR, highest rate of albuminuria > 300 mg/g and highest rate of hyperkalemia, as well as the highest median triglyceride and lowest median HDL-C levels. The rate of hypertension was highest in the northern region. Such information may be useful for healthcare planning within different areas of the country.

The main limitation of this study is that patients were recruited from specialized centers that were participating in diabetes registries, which could bias the results towards patients requiring specialist care. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes the identification of causal links between findings. We also were not able to establish a causal relationship between diabetes and CKD which would enable the identification of a cohort of patients with diabetic kidney disease. Finally, we did not verify the diagnosis of albuminuria on a subsequent occasion (or checked whether negative tests would have been positive), leaving room for variation of the true prevalence of patients with an eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria 30–300 mg/g. Strengths include the large number of participants and the routine clinical practice setting which means that the study provides evidence from real-world care. No data on the ethnicity of patients were recorded [51].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study describes the prevalence and associated morbidity burden associated with diabetic kidney disease in Germany. The data call for more attention to the presence of chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes, should trigger intensified risk factor control up and beyond the control of blood glucose and HbA1c in these patients. They may also serve as a trigger for future investigations into this patient population asking for new treatment options to be developed.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

angiotensin converting enzyme

- AntiHT:

-

antihypertensive

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BP:

-

blood pressure

- CAD:

-

chronic artery disease

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- DEGS:

-

Deutsche-Erwachsenen-Gesundheitsstudie

- DIVE:

-

Diabetes Versorgungs-Evaluation

- DPP-4:

-

dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- DPV:

-

Diabetes Patienten-Verlaufsdokumentation

- GCKD:

-

German chronic kidney disease

- GLR-1 RA:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MDRD:

-

modification of diet in renal disease formula

- MRA:

-

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

- PAD:

-

peripheral artery disease

- RAAS:

-

renin angiotensin aldosterone system

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- SGLT-2:

-

sodium–glucose co transporter-2

- T2DM:

-

type 2 diabetes

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglycerides

- UKPDS:

-

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

References

Xie Y, Bowe B, Mokdad AH, Xian H, Yan Y, Li T, Maddukuri G, Tsai CY, Floyd T, Al-Aly Z. Analysis of the global burden of disease study highlights the global, regional, and national trends of chronic kidney disease epidemiology from 1990 to 2016. Kidney Int. 2018;94(3):567–81.

Gheith O, Farouk N, Nampoory N, Halim MA, Al-Otaibi T. Diabetic kidney disease: world wide difference of prevalence and risk factors. J Nephropharmacol. 2016;5(1):49–56.

Bailey RA, Wang Y, Zhu V, Rupnow MF. Chronic kidney disease in US adults with type 2 diabetes: an updated national estimate of prevalence based on kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) staging. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:415.

Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR. Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):2032–45.

Narres M, Claessen H, Droste S, Kvitkina T, Koch M, Kuss O, Icks A. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in the diabetic (compared to the non-diabetic) population: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147329.

Nichols GA, Deruaz-Luyet A, Hauske SJ, Brodovicz KG. The association between estimated glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria, and risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations and all-cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2018;32(3):291–7.

Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361–77.

Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda B. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–81.

de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2532–9.

Kosiborod M, Gomes MB, Nicolucci A, Pocock S, Rathmann W, Shestakova MV, Watada H, Shimomura I, Chen H, Cid-Ruzafa J, Fenici P, Hammar N, Surmont F, Tang F, Khunti K, Investigators D. Vascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: prevalence and associated factors in 38 countries (the DISCOVER study program). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):150.

Wilke T, Ahrendt P, Schwartz D, Linder R, Ahrens S, Verheyen F. Incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Germany: an analysis based on 5.43 million patients. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138(3):69–75.

Schipf S, Werner A, Tamayo T, Holle R, Schunk M, Maier W, Meisinger C, Thorand B, Berger K, Mueller G, Moebus S, Bokhof B, Kluttig A, Greiser KH, Neuhauser H, Ellert U, Icks A, Rathmann W, Volzke H. Regional differences in the prevalence of known Type 2 diabetes mellitus in 45-74 years old individuals: results from six population-based studies in Germany (DIAB-CORE Consortium). Diabet Med. 2012;29(7):e88–95.

Muller N, Heller T, Freitag MH, Gerste B, Haupt CM, Wolf G, Muller UA. Healthcare utilization of people with type 2 diabetes in Germany: an analysis based on health insurance data. Diabet Med. 2015;32(7):951–7.

Waldeyer R, Brinks R, Rathmann W, Giani G, Icks A. Projection of the burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Germany: a demographic modelling approach to estimate the direct medical excess costs from 2010 to 2040. Diabet Med. 2013;30(8):999–1008.

Du Y, Heidemann C, Schaffrath Rosario A, Buttery A, Paprott R, Neuhauser H, Riedel T, Icks A, Scheidt-Nave C. Changes in diabetes care indicators: findings from German national health interview and examination surveys 1997–1999 and 2008–2011. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000135.

Danne T, Kaltheuner M, Koch A, Ernst S, Rathmann W, Russmann HJ, Bramlage P, Studiengruppe D. “DIabetes Versorgungs-Evaluation” (DIVE)—a national quality assurance initiative at physicians providing care for patients with diabetes. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013;138(18):934–9.

Bramlage P, Bluhmki T, Rathmann W, Kaltheuner M, Beyersmann J, Danne T, Group DS. Identifying patients with type 2 diabetes in which basal supported oral therapy may not be the optimal treatment strategy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;116:127–35.

Ulm University. Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdokumentation (DPV) http://buster.zibmt.uni-ulm.de/dpv/index.php/en/. Accessed 7 Jan 2019.

Bohn B, Schofl C, Zimmer V, Hummel M, Heise N, Siegel E, Karges W, Riedl M, Holl RW. initiative DPV: achievement of treatment goals for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction or stroke in 29,325 patients with type 2 diabetes: a German/Austrian DPV-multicenter analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):72.

Schwab KO, Doerfer J, Hungele A, Scheuing N, Krebs A, Dost A, Rohrer TR, Hofer S, Holl RW. Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in children with diabetes: proposed treatment recommendations based on glycemic control, body mass index, age, sex, and generally accepted cut points. J Pediatr. 2015;167(6):1436–9.

Danne T, Bluhmki T, Seufert J, Kaltheuner M, Rathmann W, Beyersmann J, Bramlage P, Group DS. Treatment intensification using long-acting insulin–predictors of future basal insulin supported oral therapy in the DIVE registry. BMC Endocr Disord. 2015;15:54.

Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El Nahas M, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, Kasiske BL, Eckardt KU. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: a KDIGO controversies conference report. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):17–28.

KDIGO 2012. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Chapter 1: definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:19–62.

Schwandt A, Denkinger M, Fasching P, Pfeifer M, Wagner C, Weiland J, Zeyfang A, Holl RW. Comparison of MDRD, CKD-EPI, and Cockcroft–Gault equation in relation to measured glomerular filtration rate among a large cohort with diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2017;31(9):1376–83.

Ozieh MN, Dismuke CE, Lynch CP, Egede LE. Medical care expenditures associated with chronic kidney disease in adults with diabetes: United States 2011. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(1):185–90.

Vupputuri S, Kimes TM, Calloway MO, Christian JB, Bruhn D, Martin AA, Nichols GA. The economic burden of progressive chronic kidney disease among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2014;28(1):10–6.

Muller G, Kluttig A, Greiser KH, Moebus S, Slomiany U, Schipf S, Volzke H, Maier W, Meisinger C, Tamayo T, Rathmann W, Berger K. Regional and neighborhood disparities in the odds of type 2 diabetes: results from 5 population-based studies in Germany (DIAB-CORE consortium). Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(2):221–30.

Girndt M, Trocchi P, Scheidt-Nave C, Markau S, Stang A. The prevalence of renal failure. Results from the German health interview and examination survey for adults, 2008–2011 (DEGS1). Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(6):85–91.

Titze S, Schmid M, Kottgen A, Busch M, Floege J, Wanner C, Kronenberg F, Eckardt KU, Investigators GS. Disease burden and risk profile in referred patients with moderate chronic kidney disease: composition of the German chronic kidney disease (GCKD) cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(3):441–51.

Velho G, Ragot S, El Boustany R, Saulnier PJ, Fraty M, Mohammedi K, Fumeron F, Potier L, Marre M, Hadjadj S, Roussel R. Plasma copeptin, kidney disease, and risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in two cohorts of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):110.

Zobel EH, von Scholten BJ, Reinhard H, Persson F, Teerlink T, Hansen TW, Parving HH, Jacobsen PK, Rossing P. Symmetric and asymmetric dimethylarginine as risk markers of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality and deterioration in kidney function in persons with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):88.

Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: UK prospective diabetes study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1832–9.

Owusu Adjah ES, Bellary S, Hanif W, Patel K, Khunti K, Paul SK. Prevalence and incidence of complications at diagnosis of T2DM and during follow-up by BMI and ethnicity: a matched case–control analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):70.

Low S, Zhang X, Wang J, Yeoh LY, Liu YL, Ang SF, Subramaniam T, Sum CF, Lim SC. The impact of HbA1c trajectories on chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.13533.

Busch M, Nadal J, Schmid M, Paul K, Titze S, Hubner S, Kottgen A, Schultheiss UT, Baid-Agrawal S, Lorenzen J, Schlieper G, Sommerer C, Krane V, Hilge R, Kielstein JT, Kronenberg F, Wanner C, Eckardt KU, Wolf G, Investigators GS. Glycaemic control and antidiabetic therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease—cross-sectional data from the German chronic kidney disease (GCKD) cohort. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):59.

Bakris GL, Weir MR, Shanifar S, Zhang Z, Douglas J, van Dijk DJ, Brenner BM. Effects of blood pressure level on progression of diabetic nephropathy: results from the RENAAL study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1555–65.

Pohl MA, Blumenthal S, Cordonnier DJ, De Alvaro F, Deferrari G, Eisner G, Esmatjes E, Gilbert RE, Hunsicker LG, de Faria JB, Mangili R, Moore J Jr, Reisin E, Ritz E, Schernthaner G, Spitalewitz S, Tindall H, Rodby RA, Lewis EJ. Independent and additive impact of blood pressure control and angiotensin II receptor blockade on renal outcomes in the irbesartan diabetic nephropathy trial: clinical implications and limitations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(10):3027–37.

Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, Chiang JL, de Boer IH, Goldstein-Fuchs J, Hirsch IB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Narva AS, Navaneethan SD, Neumiller JJ, Patel UD, Ratner RE, Whaley-Connell AT, Molitch ME. Diabetic kidney disease: a report from an ADA consensus conference. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2864–83.

Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–9.

Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, Leehey DJ, McCullough PA, O’Connor T, Palevsky PM, Reilly RF, Seliger SL, Warren SR, Watnick S, Peduzzi P, Guarino P. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1892–903.

Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, Dyal L, Schumacher H, Pogue J, Wang X, Maggioni A, Budaj A, Chaithiraphan S, Dickstein K, Keltai M, Metsarinne K, Oto A, Parkhomenko A, Piegas LS, Svendsen TL, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9638):547–53.

Rossing K, Schjoedt KJ, Smidt UM, Boomsma F, Parving HH. Beneficial effects of adding spironolactone to recommended antihypertensive treatment in diabetic nephropathy: a randomized, double-masked, cross-over study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2106–12.

Epstein M, Williams GH, Weinberger M, Lewin A, Krause S, Mukherjee R, Patni R, Beckerman B. Selective aldosterone blockade with eplerenone reduces albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):940–51.

Bolignano D, Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Strippoli GF. Aldosterone antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007004.pub3.

Athyros VG, Doumas M, Imprialos KP, Stavropoulos K, Georgianou E, Katsimardou A, Karagiannis A. Diabetes and lipid metabolism. Hormones (Athens). 2018;17(1):61–7.

Sacks FM, Hermans MP, Fioretto P, Valensi P, Davis T, Horton E, Wanner C, Al-Rubeaan K, Aronson R, Barzon I, Bishop L, Bonora E, Bunnag P, Chuang LM, Deerochanawong C, Goldenberg R, Harshfield B, Hernandez C, Herzlinger-Botein S, Itoh H, Jia W, Jiang YD, Kadowaki T, Laranjo N, Leiter L, Miwa T, Odawara M, Ohashi K, Ohno A, Pan C, Pan J, Pedro-Botet J, Reiner Z, Rotella CM, Simo R, Tanaka M, Tedeschi-Reiner E, Twum-Barima D, Zoppini G, Carey VJ. Association between plasma triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and microvascular kidney disease and retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a global case–control study in 13 countries. Circulation. 2014;129(9):999–1008.

Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137–88.

Palsson R, Patel UD. Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(3):273–80.

Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(2):302–8.

Maier W, Holle R, Hunger M, Peters A, Meisinger C, Greiser KH, Kluttig A, Volzke H, Schipf S, Moebus S, Bokhof B, Berger K, Mueller G, Rathmann W, Tamayo T, Mielck A. The impact of regional deprivation and individual socio-economic status on the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes in Germany. A pooled analysis of five population-based studies. Diabet Med. 2013;30(3):e78–86.

Mathur R, Dreyer G, Yaqoob MM, Hull SA. Ethnic differences in the progression of chronic kidney disease and risk of death in a UK diabetic population: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020145.

Authors’ contributions

EH, SF, CHJH, MF, and TD contributed to the data collection. PB, SL, and GvM designed the analysis, drafted the manuscript and created figures. SL and RWH were responsible for the statistical analyses. EH, SF, CHJH, MF, JS, TD and RWH contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. RWH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating centers of the DPV and DIVE initiatives, especially those who collaborated in this investigation.

Competing interests

JS and TD report grants and personal fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. PB reports to have received consultancy honoraria from Sanofi and Abbott. SL, GvM, EH, SF, CHJH, MF, and RWH declares that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The DPV initiative, which was established in 1995, was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Ulm, and data collection was approved by local review boards.

The DIVE registry was established in Germany in 2011 [16, 17, 21]. Consecutive patients with diabetes mellitus, regardless of their disease stage, were enrolled from centers across the country, and continue to be followed up. Data are entered into an online database using DIAMAX (Axaris, Ulm, Germany) or DPV software. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School of Hannover, and all patients included in the DIVE registry provided written informed consent.

Funding

The DPV registry was supported by the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD). Further financial support was provided by the German Diabetes Society (DDG) and the German Centre for Diabetes Research (DZD). The DIVE registry received funding from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Abbott and was conducted under the auspices of diabetesDE. Funders were not involved in study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Patient characteristics by region of Germany (overall study population). Legend: Median (Q1; Q3) or percent (%). BP = blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC = total cholesterol; TG = triglycerides; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Drug treatment by comorbidity. Legend: Percent (%). ‡Defined as eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 OR eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and overt albuminuria. CKD = chronic kidney disease; DPP-4 = dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1 RA = glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT-2 = sodium-glucose co-transporter-2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bramlage, P., Lanzinger, S., van Mark, G. et al. Patient and disease characteristics of type-2 diabetes patients with or without chronic kidney disease: an analysis of the German DPV and DIVE databases. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0837-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0837-x