Abstract

Women represent 70% of the global health workforce but only occupy 25% of health and social care leadership positions. Gender-based stereotypes, discrimination, family responsibilities, and self-perceived deficiencies in efficacy and confidence inhibit the seniority and leadership of women. The leadership inequality is often compounded by the intersection of race and socio-economic identities. Resolving gender inequalities in healthcare leadership brings women’s expertise to healthcare decision making, which can lead to equity of healthcare access and improve healthcare services. With the aim of enhancing women’s advancement to leadership positions, a rapid realist review (RRR) was conducted to identify the leadership and career advancement interventions that work for women in healthcare, why these interventions are effective, for whom they are effective, and within which contexts these interventions work. A RRR ultimately articulates this knowledge through a theory describing an intervention’s generative causation. The Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) for conducting a realist synthesis guided the methodology. Preliminary theories on leadership and career advancement interventions for women in healthcare were constructed based on an appraisal of key reviews and consultation with an expert panel, which guided the systematic searching and initial theory refinement. Following the literature search, 22 studies met inclusion criteria and underwent data extraction. The review process and consultation with the expert panel yielded nine final programme theories. Theories on programmes which enhanced leadership outcomes among women in health services or professional associations centred on organisational and management involvement; mentorship of women; delivering leadership education; and development of key leadership skills. The success of these strategies was facilitated by accommodating programme environments, adequacy and relevance of support provided and programme accessibility. The relationship between underlying intervention entities, stakeholder responses, contexts and leadership outcomes, provides a basis for underpinning the design for leadership and career advancement interventions for women in healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

“Healthcare is delivered by women but led by men”— women are grossly underrepresented in leadership relative to their participation in the health workforce [1]. They represent 70% of the global healthcare workforce and 59% of medical, biomedical and health science degree holders [1, 2]. Nonetheless, women only occupy 25% of health and social care leadership positions [3]. Moreover, women typically assume lower-status and lower-paying jobs in health and social care [1]. Gender-based stereotypes and discrimination inhibit the leadership and seniority of women, which may be compounded by intersection with race and socio-economic identities [1]. These inequalities reduce career satisfaction, morale and lifetime income among women [1].

Gender inequality is a pressing human right and socioeconomic issue with downstream outcomes such as poorer health among women [1, 3]. Addressing gender inequalities may increase the number of role models and mentors for women [1, 3]. Women role models and mentors influence career advancement as they can advise on balancing career and family and counsel on career progression opportunities [4]. Instituting women leaders may also improve the attitude towards their leadership, and enhance identification of leadership with women peers [5]. The presence of women leaders creates a platform for greater emphasis on issues that impact women and girls such as sexual and reproductive health [1, 3]. Projections from the World Health Organization (WHO) Gender Equity Hub of the Global Health Workforce Network indicate that addressing gender inequalities will accelerate the attainment of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets [1]. Progression towards gender parity will also fuel economic growth, and has been estimated as translating to a global gross domestic product increase of US$12 trillion within a decade [6]. More broadly, increasing opportunity for the participation of women is an investment towards organisational success, national prosperity, and quality of life [2].

Extant literature in the field of gender and leadership primarily focuses on barriers that hinder the uptake of leadership positions among women, with a smaller subset focusing on potentially effective strategies to advance women’s leadership [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Barriers that inhibit women’s leadership include decreased capacity owing to career disruption and family responsibilities, unfavourable credibility assumptions, and perceived deficiencies in self-efficacy and confidence [2]. The literature on interventions which advance women’s leadership highlights that these interventions engender career advancement among women, promote knowledge and skill acquisition, enhance wellbeing and morale, encourage staff retention, augment remuneration, and progress organisational culture and practices towards gender equity [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Systematic reviews and literature summaries on this topic exhibit certain oversights, such as insufficient description of primary studies, inadequate focus on research in the healthcare context, and lack of a standardised approach in evaluating the research [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Further limitations are that many studies focus on single intervention strategies (i.e., mentoring, networking), insufficiently describe intervention components, use variable terminology to define similar intervention concepts, have poor methodological rigour, display wide heterogeneity in outcomes measured, and exhibit missing process evaluations [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, there is little to no research in low and middle-income contexts (LMICs) and a paucity of system-based or culture focused interventions [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

With these limitations in mind, evidence synthesis on leadership and career advancement interventions for women needs to examine why certain programmes are more or less likely to work in certain ways, for specific people and in particular circumstances through contributing to theory [14]. A theory is transferable and applicable across a range of circumstances [14]. The links between interventions, contexts in which these interventions are implemented, participant responses to interventions, and outcomes of interventions are not evident in the existing literature [14]. This gap is consequential to the design of reviews that do not provide insight on how programmes work and how this may change based on settings or circumstances of key actors [14].

Establishing evidence-based programme theories on women’s leadership and career advancement interventions, especially, for healthcare workers is relevant for global and national policy [15, 16]. Gender equality is an objective and driver for attaining the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals [15]. Accordingly, the aim of our research is to identify what leadership and career advancement interventions work for women in healthcare, why exactly these interventions are effective, for whom specifically they are effective, and the contexts of operation. Although not part of the current research, review findings will partially inform the development of a leadership and career advancement intervention for women within the Tanzanian healthcare setting.

Methods

Design

A rapid realist review (RRR) was conducted to answer the research question, “What leadership and career advancement interventions work for women in healthcare, why exactly are these interventions effective, for whom specifically are they effective, and in what contexts?”. The RRR is described as ‘rapid’ because the search is expedited by reducing the number of databases searched and decreasing iterations within the synthesis [14]. A RRR ultimately provides a theory that indicates what programmes are likely to work, for a specific target group and under a particular set of circumstances [14]. Uncovering theories can improve the effectiveness, acceptability, transferability, and sustainability of programmes [17]. A key advantage of the RRR methodology is that it is responsive to local policy needs, and results are utility-focused [14]. The RRR approach is appropriate because this methodology effectively dissects complex programmes by scrutinising what components work, for whom exactly, under what circumstances, and why this is the case [18].

A RRR uncovers the generative causation of a phenomenon, which is expressed as a context mechanism and outcome configuration (CMOc) [18]. Context (C) can be defined as environments and pre-existing conditions within which interventions are introduced [18]. Mechanisms (M) are underlying intervention entities, processes, and structures that operate to generate outcomes (O) [18]. Mechanisms are a combination of resources (R1) introduced and the stakeholder’s reasoning (R2) in response to the resource [18]. Outcomes are consequential to mechanisms acting in contexts [18].

The RRR aims to uncover generative causation – the underlying causal processes that generate an outcome, either intended or unintended [14]. Generative causation which is expressed as a CMOc, describes the mechanisms triggered within specific contexts and outcomes this interaction generates [18]. Elucidating the link between these components uncovers the programme theory, which explains how the interventions work [18]. This theory is tested and continuously refined throughout the RRR [14]. The theory generated is not prescriptive but takes an explanatory approach [14].

This RRR was conducted between December 2022 and November 2023. The review design comprised of the phases: identifying existing theories, literature searching, document selection, data extraction, appraisal for richness and rigour, data synthesis, validation and programme theory refinement, and dissemination of findings [19]. Figure 1 details the steps taken within this RRR.

Expert panel

Aligned to RRR guidance and best practice, the expert panel was convened to help inform the research direction, ensure the relevance of the review to low and middle-income settings and more particularly to the Tanzanian healthcare context, and contextualise findings to ensure that the findings have real-world input. The expert panel consisted of 16 people. Tanzanian members of the expert panel were recruited during a visit to Tanzania, where a presentation was made to government officials and healthcare staff on the necessity of a contextually befitting leadership and career advancement intervention. Non-Tanzanian members of the expert panel were recruited through existing networks and by identifying key individuals involved in policy, programme implementation and research who could support this work.

Members of the expert panel included:

-

I.

Doctors, nurses and allied health professionals (nutrition and social welfare officers, diagnostic health service employees) from Tanzania – 8 members.

-

II.

International experts in gender, health systems and global health — 8 members.

The expert panel were consulted during the defining stages of the review, including the drafting of initial programme theories and refinement of final programme theories. Meetings were thus held during these two critical timepoints. The panel were asked to provide feedback after reviewing theories during in-person and online meetings (Zoom). These meetings were of varying sizes as they were based on the schedules of expert panel members. The expectation was for expert panel members to participate in at least two key meetings lasting no more than 1.5 h. Where expert panel members could not attend the meetings, feedback was solicited via email. Expert panel feedback was implemented after consultation and consensus with the core research team.

Identifying candidate and initial programme theories

Key systematic reviews on leadership and career advancement among women were identified using the keywords leadership, career, interventions, and women in the Google Scholar search engine. This initial literature scope was not meant to be exhaustive but rather to inform the research disposition. In concordance with this, five key reviews pertinent to the topic under scrutiny were identified and reviewed to identify the candidate programme theories—see Appendix 1 for information on these reviews [2, 7,8,9, 13].

From these five reviews, three candidate programme theories were constructed. These were then presented to the RRR expert panel and the wider research team, who both provided feedback. The candidate programme theories were then refined into initial programme theories (IPTs) [18, 20]. The resulting IPTs were:

-

I.

Interventions targeting women’s leadership should take a multi-component approach that targets different systems levels and different genders across different sectors. Multicomponent interventions result in the greatest skill development and career advancement for women when they combine individual growth (training, education, mentoring and networking) with wider organisational gender equity strategies (changes in organisational processes or culture) in the context of government and societal strategies.

-

II.

Mentoring with a multidimensional focus (career and other aspects of life) is central to the success of multicomponent interventions targeting skill development and career advancement among women. Mentoring produces the greatest skill development and career advancement among women when the relationship between mentor and mentee is organic/genuine, within a supportive network and the actual mentoring enacted by more experienced colleagues.

-

III.

Leadership development intervention programmes should be structured and supported by wider organisational, societal and government gender equity strategies. Using tools, resources and action plans for implementation and monitoring can support accountability and commitment, and produce measurable outcomes at the organisational level.

Literature searching

Study search terms were developed from keywords identified in the IPTs. Aligned to RRR methodology where database searches are limited, databases were restricted to CINAHL and Web of Science because the subject matter covered relevant topic areas including nursing and allied health research, healthcare sciences, and social sciences [14]. Search terms addressed the four areas of interest: leadership, interventions, healthcare, and gender. The comprehensive search strategy is detailed in Table 1. Searches were run for studies conducted among adults and published in English between January 2000 until 7th March 2023. The 2000 cut-off date was chosen because this coincided with the release of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals on the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women [21]. Members of the expert panel were also contacted twice via email with requests to recommend potentially relevant literature.

Selecting documents

Citations identified during searching were exported into software (Covidence) where duplicates were removed. Search results were initially screened by title and abstract, then by full text based on definitive criteria pertinent to the research topic (see Table 2 for relevance criteria). This screening was completed by DM, and 10% of the studies screened were counter-checked by AK at the title and abstract stage. There were less than 5% of conflicts for studies screened by DM and AK; BG acted as the arbitrator where the two reviewers could not resolve conflicts.

Evaluating richness and rigour

Papers and documents deemed relevant to the research topic were reviewed for richness. Richness assessments were based on the inclusion of sufficient depth to meaningfully contribute to theory building as indicated by having traceable CMOcs; theories of interest were either the initial programme theories or other theories relevant to the topic under scrutiny [22]. Studies were scored 1 point for each CMOc that was evident.

Rigour was applied to assess the methodological conduct of the included papers and documents. Rigour was assessed based on a yes (1) or no (0) dichotomy for the credibility of the source, appropriateness and trustworthiness of methodology used, and plausibility of the information reported [22]. Summary of richness and rigour scores can be found in Appendix 2.

Data extraction

The first phase of data extraction entailed collating information on the paper’s aims, setting, participants, design, intervention details, findings, and theoretical frameworks and models. After this data had been gathered, the richness and rigour of the papers were determined.

Data pertinent to generative causation including the context, mechanism and outcome of each CMOc was extracted and aggregated. This process entailed reading each paper and extracting information pertaining to the environmental and pre-existing conditions where interventions were introduced which was identified as the context. The details on the resources introduced, stakeholders and their responses to introduction of a resource was extracted and categorised as the mechanism. Finally, the resulting outcomes of the interaction between the introduction of resources and stakeholder responses were also identified. This information was utilised to draft CMOcs for each paper which can be found in Appendix 3.

Data synthesis

The IPTs were tested and revised in light of the newly emerging data from the CMOcs. Strategies used to test and refine programme theories included [23]:

a) Juxtaposing- contrasting evidence on mechanisms in one source to elaborate outcome patterns in another source.

b) Reconciling- identifying explanations for different outcomes by unveiling contextual differences.

c) Adjudication- clarifying reasons for contradictory study outcomes based on methodological variances.

d) Consolidation- constructing explanations for how and why dissimilar outcomes occur as pertinent to a specific context.

e) Situating- distinguishing which mechanisms were activated in specific contexts.

Results

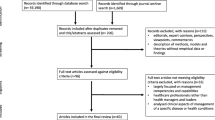

A total of 3,600 records were retrieved after searching the databases. Sixty-four duplicates were removed, leaving 3,536 papers which were screened at the title and abstract stage, after-which 3,472 were excluded. 64 papers underwent full text screening of which ten were automatically excluded due to the absence of a full text. During full text screening, 32 papers were excluded for various reasons (see Fig. 2), leaving a total of 22 studies that met inclusion criteria and underwent data extraction.

After the first phase of data extraction, only 12 studies were appraised as rich because they contributed to CMOcs, subsequently supporting theory development. These 12 studies were also rated for rigour. Appendix 2 presents a summary of ratings for richness and rigour.

A total of 29 CMOcs were extracted from the included 12 studies. Appendix 3 presents a full list of CMOcs. From these CMOcs, nine demi-regularities or patterns were identified, which supported the refinement of the programme theories into nine final programme theories after consultative meetings with the expert panel.

Discussion

This RRR describes the robust and iterative process of developing programme theories on leadership and career advancement interventions for women in healthcare. By applying the RRR methodology, literature on the topic was appraised and the twenty nine CMOcs which were extracted pointed to the relationship between the programme components, participant responses, programme settings, and resulting outcomes [17]. Demi regularities or patterns were identified within the CMOcs, which led to the construction of 9 programme theories [17].

It was evident that programmes which applied leadership education, training and mentorship for healthcare workers who were women, and were undergirded by management buy-in, inclusion of all genders, alignment with organisational goals and workplace roles, were linked to superior outcomes. Involvement of multiple parties within the organisation and considering organisational dynamics corroborates systems theory which conveys the significance of a wholistic approach [36]. Some organisational entities support, and influence others as is the case with management and other organisational members [36]. It is therefore unsurprising that the women within the health services and professional associations demonstrated improvements in leadership skills, knowledge, confidence, along with greater access to leadership positions [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Management buy-in such as their endorsement, allocation of resources, and provision of advice regarding the best course of action, minimised planning and execution obstacles [24, 27]. On occasion, management’s endorsement was through integration of the programme to the employment role and pay, which inspired added participant commitment [24, 27].

Obtaining management buy-in provides a level of accountability from the organisation which may motivate women to participate because they view the programme positively [24]. Management’s involvement through nomination of prospective participants potentially had a validating effect on the women [25]. Managers and supervisors at work are powerful agents for demonstrating organisational support, thus their role is indispensable in programmes seeking to establish organisational backing [37].

Mentoring emerged as a core constituent of leadership and career development programmes for women in health services or professional associations [24, 25, 27, 30, 32, 33]. Pre-training on how to approach and relate with mentors seemed to contribute towards leadership skills and self-efficacy [24, 30, 31]. The mentorship enactment theory proposes that proactive communication strategies are essential for initiating, developing, maintaining and repairing mentorship relationships [38]. This pre-training likely aligned mentees and mentors to the process of mentoring, enabling them to reap the maximum benefits because it boosted their engagement and effectiveness [24, 30, 31]. The mentor-mentee dynamic is characterised by an unequal power dynamic between the duo, and some preparatory skills may be required by both parties [38].

The actual mentoring was enacted by senior or more experienced staff who role modelled, provided a sounding board for ideas and assisted mentees with identifying and developing organisationally relevant leadership competencies [27, 32, 33]. It was articulated in some studies that mentors were from different organisations or units thus were not their line managers, and the benefit of this approach is minimised conflict of interest between the mentoring pairs which may contribute constructively towards outcomes [24, 30]. This type of guidance also provided new opportunities for mentees via the network connection of mentors and guided them in the navigation of new opportunities [25]. Benefits of mentorship extended beyond the mentee, and sometimes augmented the mentor’s leadership abilities due to novelty of the role [27].

It was also apparent that providing mentees and mentors with latitude over some aspects of the mentoring boosted leadership outcomes [24]. Two of the interventions indicated that mentorship dyads met monthly however this approach was not consistent across all other studies applying mentorship [24, 30]. Decisions on frequency and scheduling of mentoring meetings, the specific focus areas of the mentoring sessions, overall expectations, and goals was often left to the discretion of the participating dyad after providing general programmatic guidelines on the mentorship process and anticipated outcomes [31]. The self-determination theory posits that humans have a need for autonomy, competence, connection and belonging [39]. When these desires are satisfied, individuals are more likely to be motivated, engaged and successful [39]. Giving mentees and mentors some autonomy may give them a sense of programmatic ownership, which may contribute positively to programme engagement and ultimately towards participant leadership competency.

Leadership education and training was the most notable focus of the interventions [24,25,26,27,28]. This was characterised by leadership and discipline-specific education delivered by content experts which led to leadership self-efficacy, confidence, knowledge, skills, desire for leadership and acquisition of leadership [24,25,26,27,28]. Learning was time-tabled, structured, and assumed majority of programmatic time and resources [24,25,26,27,28]. Delivery of leadership education is congruent with the behavioural leadership theory which asserts that the traits that distinguish leaders can be learnt [40]. Focal areas for the education included transformational leadership, communication, conflict resolution, leadership styles, project management, differences between leading and managing, belonging, quality improvement, wellness and equity [24,25,26,27,28]. Broadly, the leadership topics delivered are relevant to healthcare leadership and perpetuate productivity and growth, which may have inspired additional engagement and commitment [40]. Moreover, delivering this content via in-person and online platforms reinforced positive outcomes because the multiplicity of learning avenues improved accessibility and engagement [41].

This didactic leadership education was typically coupled with practical components, such as action learning sets, experiential learning, implementation of a project and interactive sessions [26, 27, 32, 34]. Although these elements differ quite significantly in execution, they afford an opportunity and context for participants to implement lessons from the education sessions which fortifies leadership knowledge [26, 27, 32, 34]. This is the key message conveyed in the experiential learning theory which postulates that practical experiences facilitate knowledge retention and deeper grasp of ideas [42]. This mode of training is akin to learning by doing where direct instruction is coupled with practical training, and this is superior to traditional learning that is primarily theoretical [43].

Acquisition of skills in negotiation, collaboration, networking, reflection and goal setting among the women healthcare workers was resourced in the leadership education and training, which buttressed leadership outcomes [24, 25, 28, 33, 34]. Relevance of these skills to participants’ workplace roles likely evoked engagement and commitment, contributing to favourable leadership outcomes. Leadership literature cites the importance of communication, negotiation, planning, and problem solving, which parallels the skills cited in the current programmes [44]. Relevance of these leadership skills differs based on the level of organisational responsibility, for instance, planning and problem solving are more requisite at advanced leadership levels [44]. Consequently, it is crucial for programmes to impart leadership skills which are relevant to present and proximal roles [44].

Bespoke learning aims, programme activities, leadership styles and schedule of activities were available within the leadership education and training [32, 33, 35]. This approach enhanced leadership because the programme was tailored to the interests and goals of participants which ignited motivation. Tailored education and training gained traction in recent years due to the impact on knowledge, self-efficacy and behaviour change [35, 45]. Proponents also highlight that the specificity of meeting participant and organisational needs is efficient and time sensitive [46]. Consideration of participant needs and preferences favourably impacts leadership and career development programme outcomes among women healthcare workers.

Limitations

There were ostensible limitations associated with the conduct of this review. Firstly, the leadership and career development programme components were often interlinked, and it was not always clear which components led to certain outcomes and the response of key actors within the scope of the intervention. This therefore hampered information that could be meaningfully extracted from the included studies. Additionally, detailed description of intervention methodology was not always given by the authors which rendered some of the included studies obsolete for the purpose of a RRR, which relies on meticulous reporting and appraisal of intervention mechanisms [18]. Furthermore, the interventions which were explored here generated several theories which may elicit more questions for those implementing the theories due to nuances that may emerge, however these may only be plausible to interrogate at each local level. Lastly, none of the reviewed interventions were set in a low- and middle-income context, which raised questions about the relevance of the theories generated to the Tanzanian healthcare context. The authors attempted to counter this drawback by appraising theories generated with expert panel members from the Tanzanian context to ascertain applicability but clearly more research is needed in these contexts.

Conclusions

This RRR highlights theories which may be effectual in addressing the underrepresentation of women in leadership through applying leadership and career development programmes in health services or professional associations. Following the literature review process and consultation with an expert panel, 9 theories were developed to guide the development of effective programmes which enhanced leadership outcomes pertinent to acquisition of skills, knowledge, confidence, self-efficacy, fulfillment of existing roles, leadership participation, desire for and attainment of new roles. In general, these programmes comprised of leadership education and training, alongside mentoring. Key strategies applied in the delivery of the leadership and mentorship components was alignment with the organization’s direction and involvement of personnel from management; providing mentorship pretraining, allocating mentors and allowing for co-creation during mentorship; delivering general and discipline-specific leadership education; incorporation of practical components to support leadership education; integration of hybrid learning through utility of in-person and online platforms; development of key leadership skills and creating opportunity for self-tailoring within the programme. These strategies were generally successful because of the supportive programmatic environments, adequacy and relevance of support offered and accessibility of the programmes. The finding that none of the reviewed interventions were set in a low- and middle-income countries underlines an opportunity for testing the theories in this context to comprehensively crystalise features that are suitable. The theories presented underline why, how, for whom and the contexts related to the success of leadership and career development programmes for women in healthcare and can be tested and refined further especially as it pertains to long-term outcomes such as gender equality in leadership.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- RRR:

-

Rapid realist review

- RAMESES:

-

Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- UHC:

-

Universal Health Coverage

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income contexts

- CMOc:

-

Context mechanism and outcome configuration

- R1:

-

Resources

- R2:

-

Reasoning

References

World Health Organization. Closing the leadership gap: gender equity and leadership in the global health and care workforce: policy action paper, June 2021. In: Closing the leadership gap: gender equity and leadership in the global health and care workforce: policy action paper, June 2021 edn.; 2021.

Mousa M, Boyle J, Skouteris H, Mullins AK, Currie G, Riach K, Teede HJ. Advancing women in healthcare leadership: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of multi-sector evidence on organisational interventions. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101084.

World Health Organization. Gender, equity and leadership in the global health and social workforce. In.; 2020.

Downs JA, Reif LK, Hokororo A, Fitzgerald DW. Increasing women in leadership in global health. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1103–7.

Casad BJ, Oyler DL, Sullivan ET, McClellan EM, Tierney DN, Anderson DA, Greeley PA, Fague MA, Flammang BJ. Wise psychological interventions to improve gender and racial equality in STEM. Group Processes Intergroup Relations. 2018;21(5):767–87.

Woetzel J. The power of parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth. In.; 2015.

House A, Dracup N, Burkinshaw P, Ward V, Bryant LD. Mentoring as an intervention to promote gender equality in academic medicine: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e040355.

Laver KE, Prichard IJ, Cations M, Osenk I, Govin K, Coveney JD. A systematic review of interventions to support the careers of women in academic medicine and other disciplines. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020380.

Alwazzan L, Al-Angari SS. Women’s leadership in academic medicine: a systematic review of extent, condition and interventions. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e032232.

Barfield WL, Plank-Bazinet JL, Austin Clayton J. Advancement of women in the Biomedical workforce: insights for success. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1047–9.

Plank-Bazinet JL, Bunker Whittington K, Cassidy SKB, Filart R, Cornelison TL, Begg L, Austin Clayton J. Programmatic efforts at the National Institutes of Health to promote and support the careers of women in Biomedical Science. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1057–64.

Ovseiko PV, Taylor M, Gilligan RE, Birks J, Elhussein L, Rogers M, Tesanovic S, Hernandez J, Wells G, Greenhalgh T, et al. Effect of Athena SWAN funding incentives on women’s research leadership. BMJ. 2020;371:m3975.

Lydon S, Dowd E, Walsh C, Dea A, Byrne D, Murphy AW, Connor P. Systematic review of interventions to improve gender equity in graduate medicine. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1158):300.

Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, Best A. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: rapid realist review. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–15.

THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS IN ACTION. [https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals]

MINISTRY OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GENDER AND CHILDREN. NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR GENDER DEVELOPMENT. In. Tanzania 2022.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:21–34.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. In.; 2004.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist synthesis-an introduction. ESRC Res Methods Programme. 2004;2:55.

Corey J, Vallières F, Frawley T, De Brún A, Davidson S, Gilmore B. A rapid realist review of group psychological first aid for humanitarian workers and volunteers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1452.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs.) [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/millennium-development-goals-(mdgs)#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20Millennium%20Declaration,are%20derived%20from%20this%20Declaration.].

Dada S, Dalkin S, Gilmore B, Hunter R, Mukumbang FC. Applying and reporting relevance, richness and rigour in realist evidence appraisals: advancing key concepts in realist reviews. Res Synthesis Methods. 2023;14(3):504–14.

Vareilles G, Pommier J, Marchal B, Kane S. Understanding the performance of community health volunteers involved in the delivery of health programmes in underserved areas: a realist synthesis. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):22.

Brown-DeVeaux D, Jean-Louis K, Glassman K, Kunisch J. Using a Mentorship Approach to address the underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in senior nursing Leadership. J Nurs Adm. 2021;51(3):149–55.

Kelly EH, Miskimen T, Rivera F, Peterson LE, Hingle ST. Women’s wellness through equity and leadership (WEL): a program evaluation. Pediatr (Evanston). 2021;148(Suppl 2):1.

Bradd P, Travaglia J, Hayen A. Developing allied health leaders to enhance person-centred healthcare. J Health Organ Manag. 2018;32(7):908–32.

Dyess S, Sherman R. Developing the leadership skills of new graduates to influence practice environments: a novice nurse leadership program. Nurs Adm Q. 2011;35(4):313–22.

Fitzpatrick JJ, Modic MB, Van Dyk J, Hancock KK. A Leadership Education and Development Program for Clinical nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(11):561–5.

Miskelly P, Duncan L. I’m actually being the grown-up now’: leadership, maturity and professional identity development. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2014;22(1):38–48.

Leggat SG, Balding C, Schiftan D. Developing clinical leaders: the impact of an action learning mentoring programme for advanced practice nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(11–12):1576–84.

Vatan F, Temel AB. A leadership development program through mentorship for clinical nurses in Turkey. Nurs Economic. 2016;34(5):242–50.

Hewitt AA, Watson LB, DeBlaere C, Dispenza F, Guzmán CE, Cadenas G, Tran AGTT, Chain J, Ferdinand L. Leadership Development in Counseling psychology: voices of Leadership Academy alumni. Couns Psychol. 2017;45(7):992–1016.

MacPhee M, Skelton-Green J, Bouthillette F, Suryaprakash N. An empowerment framework for nursing leadership development: supporting evidence: empowerment framework for nursing leadership development. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(1):159–69.

Leslie LK, Miotto MB, Liu GC, Ziemnik S, Cabrera AG, Calma S, Huang C, Slaw K. Training Young pediatricians as leaders for the 21st Century. Pediatr (Evanston). 2005;115(3):765–73.

Cleary M, Freeman A, Sharrock L. The development, implementation, and evaluation of a clinical leadership program for mental health nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(8):827–42.

OECD. Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges; 2017.

Sumathi GN, Kamalanabhan TJ, Thenmozhi M. Impact of work experiences on perceived organizational support: a study among healthcare professionals. AI Soc. 2015;30:261.

Ragins BR, Kram KE. The handbook of mentoring at work: theory, research, and practice. Sage; 2007.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory: Basic Psychological needs in motivation. Development, and Wellness: Guilford; 2018.

Deshwal V, Ali MA. A systematic review of various leadership theories. Shanlax Int J Commer. 2020;8(1):38–43.

10 Hybrid Learning Benefits. [https://www.edapp.com/blog/hybrid-learning-benefits/]

Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, Mainemelis C. Experiential Learning Theory: Previous Research and New Directions. In: Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles edn. Edited by Sternberg RJ, Zhang L-f. United States: Routledge; 2001: 227–248.

Gil-Lacruz M, Gracia-Pérez ML, Gil-Lacruz AI. Learning by doing and training satisfaction: an evaluation by health care professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1397.

Mumford TV, Campion MA, Morgeson FP. The leadership skills strataplex: Leadership skill requirements across organizational levels. Leadersh Q. 2007;18(2):154–66.

Kravitz RL, Tancredi DJ, Grennan T, Kalauokalani D, Street RL Jr, Slee CK, Wun T, Oliver JW, Lorig K, Franks P. Cancer Health empowerment for living without Pain (Ca-HELP): effects of a tailored education and coaching intervention on pain and impairment. PAIN®. 2011;152(7):1572–82.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews 2015(4).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Diarmuid Stokes (University College Dublin librarian) for supporting development of the search strategy. We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to the members of the expert panel who provided feedback on the theories. Finally, we are thankful for the support of President office regional authorities and local government (PO-RALG) in Tanzania who endorsed the review and were keen to provide feedback during various stages.

Funding

The research is funded by the Irish Research Council grant reference number COALESCE/2022/1714.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M. led writing of the manuscript and execution of the review. B.G. led in providing guidance on technical aspects of the rapid realist review methodology. A.K. was a second reviewer in the review process and supported selection of key papers. E.M. contributed to drafting and reviewing programme theories. All authors (D.M., B.G., A.K. and E.M.) were involved in drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics for this research has been obtained from Human Research Ethics Committee – Sciences (HREC-LS) at University College Dublin (LS-C-22-220-Mucheru) in Ireland. All those who participated in the review by providing feedback gave informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mucheru, D., McAuliffe, E., Kesale, A. et al. A rapid realist review on leadership and career advancement interventions for women in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 856 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11348-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11348-7