Abstract

One-fourth to one-third of women with endometriosis receiving first-line hormonal treatment lacks an adequate response in terms of resolution of painful symptoms. This phenomenon has been ascribed to “progesterone resistance”, an entity that was theorized to explain the gap between the ubiquity of retrograde menstruation and the 10% prevalence of endometriosis among women of reproductive age.

Nevertheless, the hypothesis of progesterone resistance is not free of controversies. As our understanding of endometriosis is increasing, authors are starting to set aside the traditionally accepted tunnel vision of endometriosis as a strictly pelvic disease, opening to a more comprehensive perspective of the condition. The question is: are patients not responding to first-line treatment because they have an altered signaling pathway for such treatment, or have we been overlooking a series of other pain contributors which may not be resolved by hormonal therapy?

Finding an answer to this question is evermore impelling, for two reasons mainly. Firstly, because not recognizing the presence of further pain contributors adds a delay in treatment to the already existing delay in diagnosis of endometriosis. This may lead to chronicity of the untreated pain contributors as well as causing adverse consequences on quality of life and psychological health. Secondly, misinterpreting the consequences of untreated pain contributors as a non-response to standard first-line treatment may imply the adoption of second-line medical therapies or of surgery, which may entail non-negligible side effects and may not be free of physical, psychological and socioeconomic repercussions.

The current narrative review aims at providing an overview of all the possible pain contributors in endometriosis, ranging from those strictly organic to those with a greater neuro-psychological component. Including these aspects in a broader psychobiological approach may provide useful suggestions for treating those patients who report persistent pain symptoms despite receiving first-line hormonal medical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It has been estimated that one-fourth to one-third of women with endometriosis receiving combined oral contraceptives (COCs) or progestins lack an adequate response to treatment in terms of resolution of painful symptoms [1]. This phenomenon has been ascribed to “progesterone resistance”, an entity that was theorized at the beginning of the third millennium to explain the gap between the ubiquity of retrograde menstruation and the 10% prevalence of endometriosis among women of reproductive age [2, 3].

Moving from the hypothesis that women who develop endometriosis may do so due to an abnormal endometrium, authors started conducting molecular studies both on the eutopic and ectopic endometrium of these patients, obtaining conflicting results. A constant of many studies, however, was the finding of a reduced expression of progesterone receptors PR-A, and especially PR-B, both in the ectopic endometrium [3,4,5,6,7] and in the eutopic endometrium [8, 9] of affected patients. In particular, the reduced expression of PR-A and PR-B, which may be responsible for an enhanced proliferation of endometrial cells, was ascribed by Wu and co-workers to the hypermethylation of the progesterone receptor promoter, caused by persistent inflammation [6]. Bulun’s group, however, speculated that a deficient methylation of the estrogen receptor ERβ promoter might be involved [4].

Moreover, studies on embrio-implantation in women with endometriosis reported an attenuated decidualization and a downregulation of various progesterone target genes during the implantation window [8,10,11].

This body of evidence may not only explain the enhanced proliferative property of endometrial cells in patients with endometriosis, and consequently the gap between retrograde menstruation and disease development. It may also partly justify the effect of endometriosis on fertility, as well as its variable response to treatment. For this reason, so-called “progesterone resistance” has been adopted in the last decades both as a pathogenic theory and as an explanation for refractoriness to progestin therapy in terms of persistence of painful symptoms, i.e., dysmenorrhea, noncyclical pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysuria and dyschezia.

Nevertheless, the hypothesis of progesterone resistance is not free of controversies. Both Bukulmez and Gentilini’s groups, for example, failed to prove a reduced expression of progesterone receptors in the endometrium of affected patients [12, 13]. Most importantly, as our understanding of endometriosis as a chronic, multifactorial, inflammatory process with a systemic nature is increasing [14], authors are starting to set aside the traditionally accepted tunnel vision of endometriosis as an estrogen-dependent and strictly pelvic disease, opening to a more comprehensive perspective of the condition, including physical and mental health [15]. The central question is: are patients not responding to standard treatment because they have an altered signaling pathway for such treatment, or have we been overlooking a series of other pain contributors which may not be resolved by hormonal therapy?

Finding an answer to this question is evermore impelling, for two reasons mainly. Firstly, because not recognizing the presence of further pain contributors adds a delay in treatment to the already existing delay in diagnosis of endometriosis, that consists on average of seven to 12 years from the onset of symptoms [14]. This delay may exacerbate the untreated pain contributors, leading to their chronicity, as well as causing adverse consequences on quality of life, psychological health, intimate relationships and daily activities [16,17,18,19,20]. Secondly, misinterpreting the consequences of untreated pain contributors as a non-response to standard first-line treatment may imply the adoption of second-line medical therapies or of surgery, which may entail non-negligible side effects and may not be free of physical, psychological and socioeconomic repercussions.

The current narrative review aims at providing an overview of all the possible pain contributors in endometriosis, ranging from those strictly organic to those with a greater neuro-psychological component. Including these aspects in a broader psychobiological approach may provide useful suggestions for treating those patients who report persistent pain symptoms despite receiving first-line hormonal medical treatment.

Brief overview of possible pain contributors in endometriosis

Pain is a complex perception, which results from the interaction between peripheral sensory inputs, their central processing, cortical activation and, finally, behavioral response [21, 22]. Briefly, nociceptive signals are conveyed from the periphery to several thalamic nuclei along the spinothalamic tract and are subsequently projected to the cortex. Multiple cortical areas are activated simultaneously and communicate with subcortical structures, in order to provide different aspects of the pain experience, such as spatial and temporal characterization, conscious perception, emotional valence, modulation of pain magnitude and cognitive elaboration [23, 24].

Persistent pain occurs when the perception of pain does not abate despite its causative agent has been eliminated [22]. This may occur due to a dysfunction in several locations of the pain pathways simultaneously. The lowering of the threshold of peripheral sensory nociceptors, which consequently respond to liminal and subliminal inputs to a greater extent, is named “peripheral sensitization” (PS). Conversely, “central sensitization” (CS) may occur when a defect in the synapses of the spinal cord and of more rostral areas including the brainstem, the thalamus and the cortex amplifies pain perception [21, 25].

Given these premises, the shift towards the inclusion of endometriosis-related persistent pain in a broader framework, which considers both peripheral and central contributors to pain, appears inevitable. In these regards, Ezra and co-workers have recently classified mind-body interrelationships in four clusters, in which the mind-body ratio is progressively increasing (cluster 1: organic conditions; cluster 2: stress-exacerbated, typically inflammatory diseases; cluster 3: functional somatic syndromes; cluster 4: conversion disorders) [26]. Owing to its organic, inflammatory, multifaceted nature, endometriosis may be situated in all the first three clusters (the fourth cluster must be categorically excluded when defining endometriosis). As such, its symptoms may be the result of the interaction of numerous contributors (Fig. 1), which we briefly overview.

Nociceptive contributors

Nociception occurs via the direct activation of peripheral pain receptors, i.e. nociceptors, which evoke excitatory currents that are conveyed to the central nervous system [27]. Over the past years, ample evidence regarding the presence of myelinated nerve fibers and of nociceptors in or near endometriotic lesions has been collected. These nociceptors are activated by the release of algogens, including inflammatory molecules, from the ectopic endometrium in the peritoneal fluid (PF) [28,29,30].

In cases of deep infiltrating endometriosis, the swelling of the foci entrapped in fibrotic tissue, the infiltration of visceral walls and the mechanical stimulation of scar tissue and adhesions may concur to the development of pain [29, 31, 32].

Inflammation and peripheral sensitization

It is not yet known if inflammation instigates or perpetuates endometriosis. What is certain is that it is an essential feature of the disease, as the presence of a widespread inflammatory environment has been proven inside and outside the pelvis of affected patients [33].

Suryawanshi and co-workers reported that endometriotic lesions possess a specific immune microenvironment, which resembles a tumor inflammatory profile [34]. In particular, pro-inflammatory cytochines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and nerve growth factor (NGF) have been found increased in the PF and within endometriotic lesions [35], while prostaglandins E2 are overexpressed within the uterine endothelial cells, due their estradiol-dependent production [36]. Also, immune cell populations appear to be altered in these patients. Neutrophil granulocytes are recruited in the PF in greater concentrations [37], as are lymphocytes [38,39,40]. Macrophages, on the other hand, display reduced phagocytic capacity compared to healthy controls [39, 41,42,43].

Causes underlying the development of chronic inflammation in endometriosis are yet to be fully understood, although debris produced by retrograde menstrual blood flow seem to be involved [44]. However, the role of so-called peripheral neuroinflammation, i.e. the vicious circle by which peripheral nerve endings secrete pro-inflammatory neuromodulators in response to their infiltration by macrophages, is gaining increasing attention [43, 45]. Recent evidence supports the hypothesis that neuroinflammation may be the underlying cause of PS, the process by which defective peripheral sensory nociceptors cause hyperalgesia, an exaggerated perception of painful stimuli [43]. Moreover, an imbalance between an increased density of sensory nerve fibers, which release pro-inflammatory transmitters, and a decreased density of sympathetic nerves, which may induce an anti-inflammatory effect, has been found in endometriotic lesions [46, 47].

Therefore, inflammation and pain appear to be tightly intertwined in a mechanism by which one maintains and aggravates the other, thus causing PS [27, 48].

Central sensitization and chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs)

Central sensitization is a physio-pathological process whereby a patient becomes more sensitive to peripheral stimuli via central neural mechanisms, which are similar to those underlying the generation of memory [49].

The primum movens of CS is not fully known. However, it has been hypothesized that a continued peripheral input, such as inflammation, may induce sensory neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to respond at a higher frequency to nociceptive and non-nociceptive inputs. This may cause hyperalgesia, allodynia, persistence of pain perception even when the noxious input has been eliminated and an increase in the receptive field size [21, 26]. A poor functioning of more rostral structures such as the periaqueductal gray area, which is deputed to endogenous analgesia, has also been described in patients with CS [49, 50]. These individuals, in fact, show an increased sensitivity to experimental nociceptive stimuli also in areas of the body not related to the primary disease [51]. Lastly, CS is often accompanied by psychological responses such as catastrophic misinterpretation, selective attention and fear-based conditioning, and by constitutional symptoms such as sleep disturbances, cognitive dysfunction and asthenia [26, 51].

The role of CS in the development and in the perception of endometriosis-related pain is being increasingly reported by the literature [14, 21]. Not only, endometriosis has been included in the National Institutes of Health Pain Consortium list of Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs), a set of chronic pain conditions which often co-occur, appear to share CS as a common underlying mechanism and are often associated with mood disorders [51].

Interestingly, studies on women suffering from endometriosis report that those with a greater central component to pain are less responsive to treatment [52, 53]. In their study, Raimondo and co-workers reported a 41.4% prevalence of CS among 285 consecutive women with endometriosis. Moderate to severe pain symptoms, except for dyschezia, were significantly more frequent in the CS group and the rate of failure of first-line hormonal treatment was greater among these patients compared to the non-CS group [52]. Similarly, Orr and colleagues found more severe ratings of pain, an earlier onset of pain and a greater probability of non-response to hormonal therapy among women with endometriosis and signs of CS [53].

Myofascial contributors

The musculoskeletal system is often overlooked in the evaluation of chronic pelvic pain, mainly due to the fact that care providers don’t feel adequately knowledgeable in this regard [54]. However, it has been extensively proven that the central elaboration of repeated peripheral nociceptive inputs may induce the development of viscero-somatic reflexes which result in an increased muscle tone in the pain-related area [55]. The contracture of the muscle tissue and of its related fascia may lead to the generation of myofascial trigger points, hard, palpable nodules which are painful upon compression. Trigger point-associated pain may be due both to a high local concentration of inflammatory algogens and to muscle hypoxia and acidosis due to prolonged muscle contraction [54].

According to Till and co-workers, myofascial contribution to pain may be recognized in as many as 60–90% of women with chronic pelvic pain, including those with endometriosis [51]. These patients typically report hypertonus-related pain as non-cyclic soreness, cramping, stabbing or throbbing in the lower abdomen, often described as “ovarian pain”. Pain may also radiate to pelvic organs such as the vagina, the vulva, the bladder or the rectum, and to musculoskeletal districts such as the hips, the buttocks or the lower limbs. Dyspareunia may be a further expression of myofascial pain [51, 54]. In a recent study on 30 women with endometriosis, although 77% were using hormonal treatment, 97% reported non-menstrual pelvic pain. All participants were found to have pelvic floor spasm and myofascial trigger points and all acknowledged the pelvic floor as a major focus of their pelvic pain [56].

Psychological contributors

The triad anxiety, depression and fatigue is a common trait of many chronic inflammatory diseases, including endometriosis [15, 39, 57]. Further mental health comorbidities include bipolar disorder (OR 6), alcohol/drug dependency (3.5%), eating disorders (1.5-9%) and hyperactivity disorder (4%) [58,59,60,61]. Early psychological and physical trauma has also been found in these patients [62].

Impaired psychological health in individuals with endometriosis has been traditionally related to the presence of pain symptoms, especially chronic pelvic pain, and to the overall psychosocial burden of living with the disease. However, recent studies provided evidence of a more complex interaction among multiple factors – including inflammation, central sensitization, hormonal treatment, genetic predisposition, and the overall impact of endometriosis, especially when symptomatic – that may explain the prevalence of psychological symptoms in this population [15, 58, 63].

As the understanding of mind-body interrelations increases, the connection between pain and psychological health in a vicious-circle manner is becoming progressively evident. Psychological distress and dysfunctional pain management, including catastrophizing, may in fact increase the perception of pain by acting on central synapses and by inducing hypertonus of the pelvic myofascial structures, which are particularly vulnerable to psychological stress [27, 64]. At the same time, dealing with endometriosis-related pain remains an important cause of psychological suffering [27].

Management of pain contributors in endometriosis

Although brief, our overview aims to highlight the necessity of an open-minded, comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach when treating patients affected by endometriosis. In fact, we agree with Till and co-workers that the optimal management of chronic pain conditions must address all peripheral and central contributors [51]. Failing to diagnose and treat, if necessary, all possible etiologic factors may lead physicians on the slippery slope of believing hormonal treatment is not effective, when it may actually be necessary but not sufficient to treat patients exhaustively.

Treatment of nociceptive pain

This form of pain is generally well managed with first-line hormonal treatment (COCs or progestins) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). While the former arrest ovulation, and as such the cycle-related release of algogens, the latter inhibit cyclooxygenase, further decreasing the levels of prostaglandins [53]. In cases of deep lesions, symptoms are controlled by first-line hormonal treatment in about two thirds of patients. Progestins in fact induce atrophy of the ectopic endometrium, contrasting its infiltration of pelvic organs [65].

Reduction of inflammation

Targeting deregulated immune pathways may represent a potential avenue for novel therapeutic strategies in endometriosis [39, 44]. Currently, however, no such treatment is available for clinical use.

Various authors have studied the effectiveness of regular physical activity and of anti-inflammatory diets as a way to reduce inflammation, and thus improve painful symptoms.

Regular physical exercise appears to increase systemic levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases [66]. In women with endometriosis, exercise may further prove beneficial as it increases sex hormone-binding globulin levels, thus reducing estrogen levels [67]. Despite such evidence, in their systematic review, Hansen and colleagues failed to prove any beneficial effect of exercise on pain perception in women with endometriosis [68]. However, the six studies included in the review were based on low quality, heterogeneous data and were conducted on small cohorts of women.

Regarding dietary interventions, in 2022 Nirginakis and co-workers investigated their effect on endometriosis-related painful symptoms by conducting a systematic review of the literature. Results included weak evidences regarding possible advantages of a Mediterranean diet; antioxidant supplementation with vitamins (B6, A, C, E), mineral salts (Ca, Mg, Se, Zn, Fe), lactic ferments, fish oil (omega-3/6); a gluten-free diet and a low intake of fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP diet) - the latter was analyzed in a population of women suffering both from endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome -.

Mediterranean diet, among all, has well-known antioxidant effects. In particular, extra virgin olive oil displays a similar structure to the molecule ibuprofen, and as such is able to inhibit cyclooxygenase. This considered, although evidence regarding its efficacy on symptom relief is scarce, the authors concluded that clinicians may suggest this type of diet to patients with endometriosis as a long-term dietary change [66].

Treatment of central sensitization

It has been hypothesized that the contribution of CS to pain perception is not comparable in all patients suffering from the same chronic pain condition 69. For this reason, two self-reported questionnaires have been created and validated to aid physicians in the assessment of CS-related symptoms in clinical practice. These include the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI), a 25-item questionnaire which investigates both CS-related symptoms and the presence of other COPCs (scores ≥ 40 are indicative of CS) 69; and the 2011 Fibromyalgia Survey Score, which analyzes the total number of painful areas on a body map and the severity of such pain. The latter questionnaire may be used to diagnose both fibromyalgia and the degree of CS in other chronic pain conditions [62].

Various pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments have been suggested to manage CS, often with modest or conflicting results, mainly due to the fact that the mechanisms behind CS are not fully understood yet.

The limited evidence regarding pharmacological treatments includes studies on antidepressants, centrally acting muscle relaxants, antiepileptic drugs and cannabinoids.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are the most commonly used antidepressants for the treatment of chronic pain conditions. Their efficacy in decreasing pain sensitivity is mediated by the inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake in the descending pain modulatory pathways. TCAs may cause bothersome side effects more frequently compared to SNRIs and are associated with less robust improvement [70, 71]. Interestingly, in a recent overview of 26 systematic reviews, Ferreira and co-workers failed to find high certainty evidence regarding the effectiveness of antidepressants for chronic pain conditions, raising the question whether they should be routinely prescribed in these patients [72].

Centrally acting muscle relaxants, such as cyclobenzaprine, also inhibit norepinephrine uptake, and may play a role in reducing the hypertonus of pelvic muscles [51].

The prescription of gabapentinoids in the treatment of CS is debated. These centrally acting calcium channel blockers are typically used in the treatment of epilepsy but are also extensively used in neuropathic pain conditions as they decrease activity in the ascending pain pathways, as well as having some membrane stabilization activity [51]. Their efficacy in chronic pelvic pain appears to be limited, probably due to the fact that neuropathic pain is not the main mechanism in the etiopathogenesis of this condition. In their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Horne and colleagues failed to find a significant reduction in pain scores among patients receiving Gabapentin, in spite of an increased risk of drug-related side effects, as compared to placebo [73].

In the intent of overcoming the flaw in medical treatment of CS, researchers have analyzed the possible therapeutic role of cannabinoids. However, evidence regarding their efficacy or safety is still limited [74,75,76].

As what regards evidence on non-pharmacological treatments of CS, this is mainly low quality and includes studies on physical exercise, psychotherapy and acupuncture.

Physical exercise has been shown to improve pain, mood and sleep quality in patients suffering from chronic pain conditions. Aerobic exercise, resistance and yoga seem to be equally effective, although the reason why they are effective is still unknown. Probably their anti-inflammatory effect, the boosting of psychological well-being and of sociality, the improvement in muscle function and the increased pain tolerance due to repeated exposure to low levels of exercise-related discomfort play a role [14, 66].

In the endometriosis population, several forms of psychological interventions – such as psychological counseling and support – may help people identify a more effective and personalized strategy to manage the disease, especially in cases of negative pain management characterized by dysfunctional coping strategies, catastrophic thinking, and high levels of anxiety, which may also lead to avoidant behaviors and isolation. As regards psychotherapy, the extant endometriosis research focused on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and provided evidence that it may be effective in the context of chronic pain management [77].

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine therapy that targets specific points along “meridians” that run through the body. Its rationale in the treatment of endometriosis consists in its action on dysfunctional descending pain pathways [78]. However, its efficacy is mainly anecdotal and not supported by high quality evidence.

Nerve stimulation techniques have also been studied for the treatment of CS-related symptoms in women with endometriosis, although this kind of evidence is not yet applicable to clinical practice [79].

Assessment of other COPCs and their treatment

An important aspect in the management of CS is the diagnosis and treatment, when needed, of all co-existing COPCs. In fact, it has been proven that patients with multiple COPCs often respond less robustly to treatments which are focused on one individual COPC, leaving the other COPCs not treated [51].

Adopting simple screening measures to uncover possible co-morbid COPCs is feasible in clinical practice and may facilitate referral to an appropriate specialist. These include the Rome criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) 80; the Pain, Urgency, and Frequency (PUF) score for interstitial cystitis 81; the 2011 Fibromyagia Symptom Survey for fibromyalgia [62] and should be used for screening purposes only. These conditions are in fact often diagnoses of exclusion and as such should be carried out by specialists [51].

Treatment of myofascial pain

The recognition of a myofascial component of pain is possible through the palpation of pelvic floor muscles, typically accessed through the vagina. Although trigger points can be visualized on ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging, imaging is not necessary for diagnosis [54].

Physical therapy for the treatment of myofascial pain may incorporate manual therapy, biofeedback, trigger point injection, pain education and cognitive behavioral strategies [14, 51].

As well as in-office physical therapy, patients are often taught home exercises, which may be cost-effective and may increase compliance. Exercises include stretching practices and massages of external and internal trigger points. The latter may be self-delivered as a home exercise using an internal wand. A retrospective study on 75 women with chronic pain reported a significant improvement in pain following transvaginal physical therapy in as many as 63% of patients. The improvement in pain was proportional to the number of sessions attended [82].

Biofeedback is an instrument-based learning process by which autonomic and neuromuscular activity is measured in order to provide visual or acoustic feedback. This technique is intended to promote awareness and self-control over physiological processes [83]. However, evidence regarding its efficacy in the treatment of endometriosis-related myofascial dysfunction is still limited [84, 85].

Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, abdominal and pelvic floor injections are thought to disrupt trigger points. Two techniques may be used, the first, known as dry needling, is based on the mechanical insertion of a needle into the trigger point. The second, so-called wet needling, consists in the injection of an anesthetic solution. Injections are supposed to interrupt the pain pathway by relaxing and lengthening the muscle fiber [54].

Psychological screening and treatment

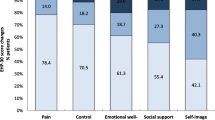

Assessing psychological health is essential when treating people with endometriosis, especially considering that patients with chronic pain and concurrent psychological conditions report more severe pain and worse quality of life compared to individuals with chronic pain alone [51, 58].

Physicians may find addressing psychological issues, including mood disorders, a challenge they are not willing to pursue, as they feel they do not possess the right skills to do so. However basic communication skills such as using open-ended questions, actively listening, expressing empathy and acknowledging personal biases and stereotypes may represent valid aids in the collection of patients’ clinical history and in the recognition of signs of mood disorders [54]. Tools such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS) [86] and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [51, 87] may also prove useful for screening but not for diagnosis and are easily applicable to clinical practice.

Referral to mental health specialists should be suggested to all patients in whom mood disorders are known or suspected. It is of uttermost importance that patients understand that such a referral is an integral part of their treatment and not a confirmation of that “the pain is all in their head”. In fact, in many instances people’s pain symptoms are not taken seriously and are normalized - especially menstrual pain -, and it is known that these negative experiences lead to delayed diagnosis and increase the physical and emotional burden of the disease [51]. Again, there is evidence that CBT can improve quality of life following surgery [88] and several trials are ongoing in women who are not candidates for surgery.

Moreover, evidence regarding the positive effect of physical activity and exercise on mental health, and particularly on anxiety, depression and sleep disorders is increasing [89].

Conclusions

According to As-Sanie and co-workers, women with endometriosis make on average seven visits to their primary health care professional before being referred to a specialist and nearly three-quarters of them receive a misdiagnosis [48]. On the basis of the evidence we have reported and summarized also in Table 1, it is arguable that those who do receive a correct diagnosis of endometriosis could still be receiving a misdiagnosis, as, in the majority of cases, only nociception is recognized and treated as a pain contributor. We hypothesize that so-called non-responders to progesterone may be the patients in whom further pain contributors such as inflammation, PS, CS, myofascial disorders and psychopathological conditions play such a relevant role that leaving them untreated represents an impediment to symptom resolution.

Further research is certainly necessary not only to confirm such hypothesis but also to identify an effective treatment for each pain contributor. Meanwhile, providing patients with a clear overview of all the different treatments they could benefit from and building realistic expectations on what such treatments entail and how they may prove useful, may represent a starting point. Diet, physical exercise, physical therapy and psychotherapy may not be sufficient to resolve patients’ symptoms but may certainly be necessary, in addition to hormonal therapy, to address the multiple pathogenic facets of endometriosis.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COCs:

-

Combined oral contraceptives

- PR-A:

-

Progesterone receptors A

- PR-B:

-

Progesterone receptors B

- ERβ:

-

Estrogen receptorsβ

- PS:

-

Peripheral sensitization

- CS:

-

Central sensitization

- PF:

-

Peritoneal fluid

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin 1β

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin 6

- IL-8:

-

Interleukin 8

- NGF:

-

Nerve growth factor

- COPCs:

-

Chronic overlapping pain conditions

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- FODMAP:

-

Fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols

- CSI:

-

Central Sensitization Inventory

- TCAs:

-

Tricyclic antidepressants

- SNRIs:

-

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- PUF:

-

Pain, Urgency, and Frequency

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

References

Becker CM, Gattrell WT, Gude K, Singh SS. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:125–136.

Vinatier D, Cosson M, Dufour P. Is endometriosis an endometrial disease? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91:113–25.

Attia GR, Zeitoun K, Edwards D, Johns A, Carr BR, Bulun SE. Progesterone receptor isoform A but not B is expressed in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2897–902.

Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, Xue Q, Attar E, Trukhacheva E, Tokunaga H, Utsunomiya H, Yin P, Luo X, Lin Z, Imir G, Thung S, Su EJ, Kim JJ. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:36–43.

Jichan Nie, Xishi Liu, Guo SW. Promoter hypermethylation of progesterone receptor isoform B (PR-B) in adenomyosis and its rectification by a histone deacetylase inhibitor and a demethylation agent. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:995–1005.

Wu Y, Starzinski-Powitz A, Guo SW. Prolonged stimulation with tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced partial methylation at PR-B promoter in immortalized epithelial-like endometriotic cells. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:234–7.

Wu Y, Strawn E, Basir Z, Halverson G, Guo SW. Promoter hypermethylation of progesterone receptor isoform B (PR-B) in endometriosis. Epigenetics. 2006;1:106–11.

Kao LC, Germeyer A, Tulac S, Lobo S, Yang JP, Taylor RN, Osteen K, Lessey BA, Giudice LC. Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2870–81.

Wingfield M, Macpherson A, Healy DL, Rogers PA. Cell proliferation is increased in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:340–6.

Burney RO, Talbi S, Hamilton AE, Vo KC, Nyegaard M, Nezhat CR, Lessey BA, Giudice LC. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3814–26.

Xue Q, Lin Z, Cheng YH, Huang CC, Marsh E, Yin P, Milad MP, Confino E, Reierstad S, Innes J, Bulun SE. Promoter methylation regulates estrogen receptor 2 in human endometrium and endometriosis. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:681–7.

Gentilini D, Vigano P, Vignali M, Busacca M, Panina-Bordignon P, Caporizzo E, Di Blasio AM. Endometrial stromal progesterone receptor-A/progesterone receptor-B ratio: no difference between women with and without endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1538–1540.

Bukulmez O, Hardy DB, Carr BR, Word RA, Mendelson CR. Inflammatory status influences aromatase and steroid receptor expression in endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1190–204..

Green IC, Burnett T, Famuyide A. Persistent Pelvic Pain in Patients With Endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;65:775–785.

Koller D, Pathak GA, Wendt FR, Tylee DS, Levey DF, Overstreet C, Gelernter J, Taylor HS, Polimanti R. Epidemiologic and Genetic Associations of Endometriosis With Depression, Anxiety, and Eating Disorders. JAMA Netw Open. 2023; 2022.51214

Missmer SA, Tu FF, Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Soliman AM, Chiuve S, Eichner S, Flores-Caldera I, Horne AW, Kimball AB, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Singh SS, Taylor HS, As-Sanie S. Impact of Endometriosis on Life-Course Potential: A Narrative Review. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:9–25.

Gambadauro P, Carli V, Hadlaczky G. Depressive symptoms among women with endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:230–241.

Facchin F, Barbara G, Buggio L, Dridi D, Frassineti A, Vercellini P. Assessing the experience of dyspareunia in the endometriosis population: the Subjective Impact of Dyspareunia Inventory (SIDI). Hum Reprod. 2022;37:2032–2041.

Facchin F, Barbara G, Dridi D, Alberico D, Buggio L, Somigliana E, Saita E, Vercellini P. Mental health in women with endometriosis: searching for predictors of psychological distress. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1855–1861.

Facchin F, Buggio L, Ottolini F, Barbara G, Saita E, Vercellini P. Preliminary insights on the relation between endometriosis, pelvic pain, and employment. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2019;84:190–195.

Marchand S. The physiology of pain mechanisms: from the periphery to the brain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:285–309.

Fenton BW, Shih E, Zolton J. The neurobiology of pain perception in normal and persistent pain. Pain Manag. 2015;5:297–317.

Pomares FB, Faillenot I, Barral FG, Peyron R. The ‘where’ and the ‘when’ of the BOLD response to pain in the insular cortex. Discussion on amplitudes and latencies. Neuroimage. 2013;64:466–75.

Wiech K, Ploner M, Tracey I. Neurocognitive aspects of pain perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:306–13.

Inquimbert P, Bartels K, Babaniyi OB, Barrett LB, Tegeder I, Scholz J. Peripheral nerve injury produces a sustained shift in the balance between glutamate release and uptake in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Pain. 2012;153:2422–2431.

Ezra Y, Hammerman O, Shahar G. The Four-Cluster Spectrum of Mind-Body Interrelationships: An Integrative Model. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:39.

Morotti M, Vincent K, Becker CM. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:8–13.

Tokushige N, Markham R, Russell P, Fraser IS. Nerve fibres in peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3001–7.

Gruber TM, Mechsner S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells. 2021;10:1381.

Anaf V, El Nakadi I, De Moor V, Chapron C, Pistofidis G, Noel JC. Increased nerve density in deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71:112–7.

Vercellini P. Endometriosis: what a pain it is. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1997;15:251–61.

Porpora MG, Koninckx PR, Piazze J, Natili M, Colagrande S, Cosmi EV. Correlation between endometriosis and pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:429–34.

Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021;397:839–852.

Suryawanshi S, Huang X, Elishaev E, Budiu RA, Zhang L, Kim S, Donnellan N, Mantia-Smaldone G, Ma T, Tseng G, Lee T, Mansuria S, Edwards RP, Vlad AM. Complement pathway is frequently altered in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6163–74.

Zhang T, De Carolis C, Man GCW, Wang CC. The link between immunity, autoimmunity and endometriosis: a literature update. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:945–955.

Gurates B, Bulun SE. Endometriosis: the ultimate hormonal disease. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:125–34.

Lin YJ, Lai MD, Lei HY, Wing LY. Neutrophils and macrophages promote angiogenesis in the early stage of endometriosis in a mouse model. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1278–86.

Klein NA, Pérgola GM, Rao-Tekmal R, Dey TD, Schenken RS. Enhanced expression of resident leukocyte interferon gamma mRNA in endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1993;30:74–81.

Symons LK, Miller JE, Kay VR, Marks RM, Liblik K, Koti M, Tayade C. The Immunopathophysiology of Endometriosis. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:748–762.

Slabe N, Meden-Vrtovec H, Verdenik I, Kosir-Pogacnik R, Ihan A. Cytotoxic T-Cells in Peripheral Blood in Women with Endometriosis. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013;73:1042–1048.

Chuang PC, Wu MH, Shoji Y, Tsai SJ. Downregulation of CD36 results in reduced phagocytic ability of peritoneal macrophages of women with endometriosis. J Pathol. 2009;21:232–41.

Greaves E, Temp J, Esnal-Zufiurre A, Mechsner S, Horne AW, Saunders PT. Estradiol is a critical mediator of macrophage-nerve cross talk in peritoneal endometriosis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2286–97.

Wu J, Xie H, Yao S, Liang Y. Macrophage and nerve interaction in endometriosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:53.

Giacomini E, Minetto S, Li Piani L, Pagliardini L, Somigliana E, Viganò P. Genetics and Inflammation in Endometriosis: Improving Knowledge for Development of New Pharmacological Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9033.

Lang BT, Wang J, Filous AR, Au NP, Ma CH, Shen Y. Pleiotropic molecules in axon regeneration and neuroinflammation. Exp Neurol. 2014;258:17–23.

Arnold J, Barcena de Arellano ML, Rüster C, Vercellino GF, Chiantera V, Schneider A, Mechsner S. Imbalance between sympathetic and sensory innervation in peritoneal endometriosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:132–41.

Miller EJ, Fraser IS. The importance of pelvic nerve fibers in endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11:611–8.

As-Sanie S, Black R, Giudice LC, Gray Valbrun T, Gupta J, Jones B, Laufer MR, Milspaw AT, Missmer SA, Norman A, Taylor RN, Wallace K, Williams Z, Yong PJ, Nebel RA. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:86–94.

Ren K, Dubner R. Pain facilitation and activity-dependent plasticity in pain modulatory circuitry: role of BDNF-TrkB signaling and NMDA receptors. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;35:224–35.

Nijs J, Lahousse A, Kapreli E, Bilika P, Saraçoğlu İ, Malfliet A, Coppieters I, De Baets L, Leysen L, Roose E, Clark J, Voogt L, Huysmans E. Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3203.

Till SR, Nakamura R, Schrepf A, As-Sanie S. Approach to Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women: Incorporating Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions in Assessment and Management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2022;49:219–239.

Raimondo D, Raffone A, Renzulli F, Sanna G, Raspollini A, Bertoldo L, Maletta M, Lenzi J, Rovero G, Travaglino A, Mollo A, Seracchioli R, Casadio P. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Central Sensitization in Women with Endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:73–80.

Orr NL, Wahl KJ, Lisonek M, Joannou A, Noga H, Albert A, Bedaiwy MA, Williams C, Allaire C, Yong PJ. Central sensitization inventory in endometriosis. Pain. 2022;163: e234–e245.

Ross V, Detterman C, Hallisey A. Myofascial Pelvic Pain: An Overlooked and Treatable Cause of Chronic Pelvic Pain. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2021;66:148–160.

Aredo JV, Heyrana KJ, Karp BI, Shah JP, Stratton P. Relating Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis to Signs of Sensitization and Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:88–97.

Phan VT, Stratton P, Tandon HK, Sinaii N, Aredo JV, Karp BI, Merideth MA, Shah JP. Widespread myofascial dysfunction and sensitisation in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Pain. 2021;25:831–840.

Chen LC, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Bai YM, Su TP, Li CT, Yang AC, Chang WH, Chen TJ, Tsai SJ, Chen MH. Risk of developing major depression and anxiety disorders among women with endometriosis: A longitudinal follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:282–285.

Maulitz L, Stickeler E, Stickel S, Habel U, Tchaikovski SN, Chechko N. Endometriosis, psychiatric comorbidities and neuroimaging: Estimating the odds of an endometriosis brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2022;65:100988.

Delanerolle G, Ramakrishnan R, Hapangama D, Zeng Y, Shetty A, Elneil S, Chong S, Hirsch M, Oyewole M, Phiri P, Elliot K, Kothari T, Rogers B, Sandle N, Haque N, Pluchino N, Silem M, O'Hara R, Hull ML, Majumder K, Shi JQ, Raymont V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Endometriosis and Mental-Health Sequelae; The ELEMI Project. Womens Health (Lond). 2021; 17:17455065211019717.

Laganà AS, Condemi I, Retto G, Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Zoccali RA, Triolo O, Cedro C. Analysis of psychopathological comorbidity behind the common symptoms and signs of endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:30–3.

Vannuccini S, Lazzeri L, Orlandini C, Morgante G, Bifulco G, Fagiolini A, Petraglia F. Mental health, pain symptoms and systemic comorbidities in women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;39:315–320.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RS, Mease P, Russell AS, Russell IJ, Winfield JB. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1113–22.

Doney E, Cadoret A, Dion-Albert L, Lebel M, Menard C. Inflammation-driven brain and gut barrier dysfunction in stress and mood disorders. Eur J Neurosci. 2022;55:2851–2894.

Elkadry E, Moynihan LK. Myofascial pelvic pain syndrome in females: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. In: UpToDate. 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/myofascial-pelvic-pain-syndrome-in-females-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis. Accessed 09 Dec 2022.

Vercellini P, Buggio L, Frattaruolo MP, Borghi A, Dridi D, Somigliana E. Medical treatment of endometriosis-related pain. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:68–91.

Nirgianakis K, Egger K, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Lanz S, Bally L, Mueller MD. Effectiveness of Dietary Interventions in the Treatment of Endometriosis: a Systematic Review. Reprod Sci. 2022;29:26–42.

Cea Soriano L, López-Garcia E, Schulze-Rath R, Garcia Rodríguez LA. Incidence, treatment and recurrence of endometriosis in a UK-based population analysis using data from The Health Improvement Network and the Hospital Episode Statistics database. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22:334–343.

Hansen S, Sverrisdóttir UÁ, Rudnicki M. Impact of exercise on pain perception in women with endometriosis: A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1595–1601.

Mayer TG, Neblett R, Cohen H, Howard KJ, Choi YH, Williams MJ, Perez Y, Gatchel RJ. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract. 2012;12:276–85.

Arnold LM. Duloxetine and other antidepressants in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2007;8 Suppl 2:S63–74.

Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015.CD008242.pub3.

Ferreira GE, Abdel-Shaheed C, Underwood M, Finnerup NB, Day RO, McLachlan A, Eldabe S, Zadro JR, Maher CG. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants for pain in adults: overview of systematic reviews. BMJ. 2023;380:e072415.

Horne AW, Vincent K, Hewitt CA, Middleton LJ, Koscielniak M, Szubert W, Doust AM, Daniels JP; GaPP2 collaborative. Gabapentin for chronic pelvic pain in women (GaPP2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:909–917.

Liang AL, Gingher EL, Coleman JS. Medical Cannabis for Gynecologic Pain Conditions: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:287–296.

Armour M, Sinclair J. Cannabis for endometriosis-related pain and symptoms: It’s high time that we see this as a legitimate treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2023;63:118–120.

Eichorn NL, Shult HT, Kracht KD, Berlau DJ. Making a joint decision: Cannabis as a potential substitute for opioids in obstetrics and gynecology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;85:59–67.

Donatti L, Malvezzi H, Azevedo BC, Baracat EC, Podgaec S. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Endometriosis, Psychological Based Intervention: A Systematic Review. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2022;44:295–303.

Armour M, Cave AE, Schabrun SM, Steiner GZ, Zhu X, Song J, Abbott J, Smith CA. Manual Acupuncture Plus Usual Care Versus Usual Care Alone in the Treatment of Endometriosis-Related Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Study. J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:841–849.

Simpson G, Philip M, Lucky T, Ang C, Kathurusinghe S. A Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Availability of Targeted Treatments for Central Sensitization in Women With Endometriosis. Clin J Pain. 2022;38:640–648.

Simren M, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Update on Rome IV Criteria for Colorectal Disorders: Implications for Clinical Practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19:15.

Brewer ME, White WM, Klein FA, Klein LM, Waters WB. Validity of Pelvic Pain, Urgency, and Frequency questionnaire in patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2007;70:646–9.

Bedaiwy MA, Patterson B, Mahajan S. Prevalence of myofascial chronic pelvic pain and the effectiveness of pelvic floor physical therapy. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:504–10.

Wagner B, Steiner M, Huber DFX, Crevenna R. The effect of biofeedback interventions on pain, overall symptoms, quality of life and physiological parameters in patients with pelvic pain: A systematic review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2022;134:11–48.

Del Forno S, Arena A, Alessandrini M, Pellizzone V, Lenzi J, Raimondo D, Casadio P, Youssef A, Paradisi R, Seracchioli R. Transperineal Ultrasound Visual Feedback Assisted Pelvic Floor Muscle Physiotherapy in Women With Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis and Dyspareunia: A Pilot Study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46:603–611.

Hawkins RS, Hart AD. The use of thermal biofeedback in the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis: preliminary findings. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2003;28:279–89.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Boersen Z, de Kok L, van der Zanden M, Braat D, Oosterman J, Nap A. Patients’ perspective on cognitive behavioural therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: a qualitative study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:819–825.

Benefits of Physical Activity. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health. Accessed 16 Jun 2022.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, Current research IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milano

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the literature review for the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by G.E.C. All authors commented on and edited the subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All named authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cetera, G.E., Merli, C.E.M., Facchin, F. et al. Non-response to first-line hormonal treatment for symptomatic endometriosis: overcoming tunnel vision. A narrative review. BMC Women's Health 23, 347 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02490-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02490-1