Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to examine changes in beverage expenditure patterns before and after a T$0.50/L sweetened-beverage (SB) excise was introduced in Tonga in 2013, by household income, household age composition and island of residence.

Methods

Two cross-sectional surveys involved households being randomly sampled (the Household Income and Expenditure Surveys in 2009 (n = 1982) and 2015/16 (n = 1800)). Changes in soft drink (taxed), bottled water, and milk (both untaxed) expenditure were examined namely: (i) prevalence of households purchasing the beverage; (ii) average expenditure per person (inflation-adjusted); (iii) expenditure as a proportion of household food budget; and (iv) expenditure per person as a proportion of equivalised income.

Results

The pattern found was of decreases in all soft drink expenditure outcomes and these appeared to be greater in low-income than high-income households for purchasing prevalence (− 30% and − 25% respectively, t-test p = 0.98), per-capita expenditure (− 37% and − 34%, p = 0.20) and food budget share (− 27% and − 7%, p = 0.65), but not income share (− 6% and − 32%, p = 0.71). The large expenditure increases in bottled water appeared to be greater in low-income than high-income households for purchasing prevalence (355 and 172%, p = 0.32) and food budget share (665 and 468%, p = 0.09), but greater in high-income households for per-capita expenditure (121 and 373%, p < 0.01) and income share (83 and 397%, p = 0.50).

Conclusions

The sweetened-beverage tax was associated with reduced soft drink purchasing and increased bottled water expenditure. Low-income households appeared to have slightly greater declines in soft drink expenditure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes have been shown to reduce purchasing and dietary intake of taxed beverages across jurisdictions [1]. However, it is unclear to what extent reductions vary by socioeconomic position (SEP) and other factors such as age, obesity, rurality and level of consumption. Heterogeneity is important because a key public health goal in many settings is to improve health equity and there is interest in which interventions work best for people with the highest health and financial needs. Modelling studies suggest SSB taxes can have both progressive health effects (pro-health equity), and also be financially regressive [2, 3], for example low-income households tend to pay more as a proportion of their income or expenditure. However, SSB taxes may typically reduce expenditure on SSBs more for low SEP than high SEP households, owing to greater price sensitivities of low-income groups. The overall fiscal burden and health benefit of SSB taxes on low-income households depends on how much consumption decreases and on substitution patterns [4], particularly to other beverages. The tax burden is typically very small and has been found to be similar in low- and high-income households [2, 5]. Earmarked revenue from SSB taxes into other health interventions may also subsequently impact on equity, as per various jurisdictions [6].

In jurisdictions that have introduced SSB taxes and evaluated them by SEP, the pattern of soft drink consumption has been mixed. Evaluations of a 1 peso/L SSB tax in Mexico have reported significantly greater SSB tax effects (% change) on per capita purchased volumes in groups with low SEP [7, 8]. Results were similar from evaluations of sales taxes in the United States where children from low-income families had larger declines in dietary intake as a result of differential state soft drink sales taxes [9]. In Chile, conversely, after a relatively small SSB tax increase from 13 to 18% in beverages with ≥ 6.25 g sugar/100 ml, two evaluations reported that the largest declines in taxed beverage purchase volumes were in high SEP groups [10, 11]. This could have been due to non-tax factors such as media coverage of the tax or other policies such as front of pack labelling [12] having more impact on better educated consumers [13]. In Catalonia, Spain, a €0.12/L SSB tax on beverages with > 8 g sugar/100 ml, was associated with greater declines in high-income regions [14], and high-income households in a second study [15], who had greater reductions in soft drink expenditure shares and grams of sugar from soft drinks [15].

Substitution impacts of SSB taxes to untaxed beverages may also vary by SEP but few real world studies have investigated this. In Mexico the post-tax increase (% change) in bottled water expenditures was higher in low- and middle-income households [7], and in a second study the highest increase (% change) in untaxed beverages was in middle-socioeconomic households [8]. It remains to be seen if the same pattern is evident in other jurisdictions. This has important potential consequences for health equity.

Variation by context suggests that equity effects may be difficult to predict and detailed country-specific analyses are recommended [4]. Results between jurisdictions may be affected by the size of the tax, extent of pass-through to beverage prices, other non-communicable disease (NCD) policy changes, pre-existing trends in beverage consumption, extent of public health messaging [13], and changes in local production and throughout the food system. Existing studies generally assessed relatively small SSB taxes (< 12%), and larger beverage tax changes such as those in Tonga may be associated with a stronger SEP pattern.

Pacific Island and Small Island Developing State SSB taxes have been rarely studied. Tonga was selected for this study because there was a relatively large 27% point increase in the size of the Tonga sweetened-beverage (SB) tax as a percentage of the import price. In August 2013 [16] a 15% import tariff on SBs was replaced with an excise of T$0.50/L (US$0.28/L, 42% of import value) and subsequently doubled to T$1.00/L in July 2016 (63% of import value). The excise applied to full sugar and artificially sweetened soft drinks, energy drinks, and other SBs coded by trade harmonised system code 22.02. The tax did not apply to water (sparkling or flat), juice (sweetened or unsweetened), powdered juice drinks, tea, coffee or hot chocolate. There was little media attention on the SB excise and awareness of the SB tax was low in 2017 [17]. No other major NCD policies were introduced in 2013, however in July 2016 (and 2017) a number of health food taxes were also introduced. The impact of the excise has been associated with reduced import volumes of taxed beverages [18] and changes in beverage purchasing behaviour (38% respondents in 2017 reported reducing their SB consumption in response to SB tax) [17]. However, it remains unclear which age, income groups and islands experienced the greatest financial costs and declines in consumption from the SB excise.

Tonga is an upper-middle-income country (World Bank) with a high dependence on imported foods (52%) [19] and vulnerability to food insecurity [20]. In 2004 two-thirds of adults in Tonga were obese, which is one of the highest rates of obesity in the world; and 17% of adults had diabetes [21] but this has likely increased subsequently. SBs are commonly consumed by children and adolescents [22] particularly in the main island of Tongatapu (approximately 70% of the population) where consumption has been recorded as fourfold greater than Ha’apai [23], an outer island group. The Tonga census has identified that most households rely on rain water tanks as their main source of drinking water with the majority relying on their own cement tank but a quarter using water from a neighbour [24].

Given this background, the aim of this study was to examine changes in taxed and untaxed beverage expenditure patterns from 2009 to 2015/16 by household income, household age composition and island region; before and after the 2013 Tonga SB excise introduction.

Methods

Data

Two cross-sectional surveys were used ie, the 2009 and 2015/16 Tonga Household Income and Expenditure Surveys (HIES). Each survey adopted a two-stage sampling strategy with stratification by island, sampling proportional to census block size and random selection of 12 households from each census block [25, 26]. The 2009 survey was collected at four time points spanning the calendar year, and the 2015/16 survey was collected in 16 rounds over 12 months (4 rounds per quarter) from October 2015 to October 2016 (Table 1). Households surveyed between July and September 2016 (26%) would have also experienced the doubling of the SB tax in to T$1.00/L from beginning of July 2016 [27]. Response rates were high at 96.1% in 2009 and 98.8% in 2015/16. A very small proportion of these households did not report any food expenditures and were excluded from the analysis (0.05 and 0.17% for each survey respectively). Thus, food and beverage expenditure data were recorded by 1982 households in 2009 and 1800 households in 2015/16.

Each household was asked to keep a diary for 2 weeks recording household expenditure, gifts received and home-produced items. The categorisation of beverages in 2015/16 was more detailed. The categories aligned to the broader 2009 beverage categories for soft drinks, milk and bottled water (see Additional File Table B for definitions and alignment). Households were also asked about the number of household members, ages, income, island, time period (annual quarter) of expenditure, main drinking water source, highest qualification, and (in 2015/16) the height and weight of each household member were collected. Children (less than 15 years old) and adults (15 years and older) were categorised in the same way as the Tonga HIES.

Outcomes

The dependent variable (outcome) was the level of expenditure on soft drinks (all brands and including artificially-sweetened beverages), milk (dairy products) and bottled water. Of these beverage categories, the 2013 and 2016 SB taxes applied fully to soft drinks. Expenditure was the value of beverages acquired, used or paid for by a household through direct monetary purchases, home production, barter and as income in-kind for consumption by household members. Four measures of expenditure were used: (i) proportion of households acquiring one or more beverages in the 2 week period (purchasing prevalence); (ii) beverage expenditure adjusted for inflation (2015/16 T$ per household member per year); (iii) beverage as a proportion of all food and non-alcoholic beverage expenditures (food budget share, a measure of household food preference [28]); and (iv) beverage expenditure per person as a proportion of equivalised household income (income share). Multiple measures were selected to improve comparability with other studies [4]. All measures were based on the total survey sample, not just beverage consumers.

Analysis

Average household expenditure outcomes in the 2009 and 2015/16 surveys were compared to assess any changes after the SB tax for taxed and untaxed beverages. The absolute differences in mean expenditure outcomes between the two surveys were calculated and t-statistics were used to assess statistical significance for the differences and calculate the 95% confidence intervals. Relative changes (% change) were calculated from survey means and standard errors were calculated using a formula derived by Fieller [29]. The same approach was carried out within each strata of household age composition (adults only, or children and adults), equivalised income tertile, and island (the main island of Tongatapu, or an outer island/island group) to examine whether post-tax changes varied. Equivalised income was calculated using the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-modified scale with a weighting of 1.0 for the first adult, 0.5 for each additional adult, and 0.3 to each child (< 14 years old). T-tests were used to assess whether the absolute changes differed between sub-group categories. A sensitivity test was carried out to remove the influence the July 2016 tax change on 2016/15 outcomes by excluding households surveyed in quarter three of both surveys (to remove the post 2016-tax period and allow for seasonal variation). Expenditure changes were then examined overall and by household income. All analyses were carried out in R using the ‘survey’ package for complex survey designs. All results adjust for survey strata, clusters and weights, to ensure results represent the national Tonga population and the true uncertainty.

Results

Table 1 describes households in each survey population. Between surveys there were small increases in mean age of household members (2.2 years), equivalised household income (T$814, a smaller increase than inflation, which is not adjusted for here), households on the main island (2.8 percentage point (absolute) increase), mean household size (0.5 persons increase), and households that reported bottled water as their main drinking water source (6.0 percentage point increase).

Changes in expenditure outcomes

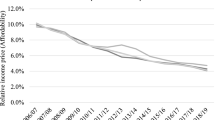

Table 2 details the post-tax changes in beverage expenditure outcomes. There was a pattern of relative decreases in soft drink: purchasing prevalence (− 21, 95% confidence interval (CI): − 29% to − 13%), real per capita expenditure (− 22%, CI: − 44 to 3%), food budget share (− 5%, CI: − 26 to 17%), and income share (− 17%, CI: − 45 to 13%, Fig. 1). Conversely, there were large and typically significant increases in bottled water: purchasing prevalence (237%, CI: 176 to 306%), expenditure (341%, CI: 156 to 621%), food budget share (533%, CI: 231 to 906%) and income share (234%, CI: − 64 to 1072%, Fig. 2). In the same direction there were significant increases in milk purchasing: prevalence (49%, CI: 31 to 68%), expenditure (56%, CI: 21 to 94%), food budget share (94, 59 to 132%), and income share (43%, CI: 12 to 79%). The sensitivity test demonstrated similar declines in soft drink expenditure outcomes (Additional File Table S4a).

Comparison of 2009 and 2015/16 soft drink expenditure outcomes in Tonga. Notes: Household income was equivalised by household age composition using the OECD measure (see Methods) and categorised into tertiles. Expenditure was inflation adjusted. Food expenditure (used to calculate food budget share) excludes takeaway expenditures. All measures include all households. Increases and decreases are a comparison of 2015/16 outcomes after SB tax introduction with 2009 outcomes. Data source: Tonga Household Income and Expenditure Survey data, Department of Statistics, Tonga

Comparison of 2009 and 2015/16 bottled water expenditure outcomes in Tonga. Notes: Household income was equivalised by household age composition using the OECD measure (see Methods) and categorised into tertiles. Expenditure was inflation adjusted. Food expenditure (used to calculate food budget share) excludes takeaway expenditures. All measures include all households. Increases and decreases are a comparison of 2015/16 outcomes after SB tax introduction with 2009 outcomes. Data source: Tonga Household Income and Expenditure Survey data, Department of Statistics, Tonga

Changes in expenditure by household income, household composition and island

The decreases in soft drink expenditure and increases in other beverage expenditure appeared to differ by household income per capita, age composition of the household, and island; but patterns differed between absolute and relative measures of change and some may have been due to chance (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). Relative changes are summarised here for international comparability.

The soft drink declines in expenditure outcomes showed a pattern of being somewhat greater in low-income than high-income households. This was for purchasing prevalence (low-income: − 30% and high-income:-25%, p = 0.98), per capita expenditure (− 37% and − 34%, p = 0.20) and food budget share (− 27% and − 7%, p = 0.65), but not income share (− 6% and − 32%, p = 0.71) (Fig. 1, Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). For middle-income households there was a smaller decline in soft drink purchasing prevalence, and indeed small increases in soft drink expenditure, food budget share and income share. Declines were greater in adult only households compared to households with children for soft drink purchasing prevalence, average expenditure and food budget share (income share declines were similar in both). Declines in purchasing prevalence and income share were greater in Tongatapu households; whereas declines in food budget share appeared to be greater in outer island households (expenditure declines were similar by island type).

The increases in bottled water showed a pattern of being greater in low-income than high-income households. This was for purchasing prevalence (355 and 172% respectively, p = 0.32) and food budget share (665 and 168%, p = 0.09) but increases were greater in high-income households for per capita expenditure (121 and 373%, p < 0.01), and income share (83 and 397%, p = 0.50) (Fig. 2, Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). Adult only households appeared to have greater increases in bottled water food budget share, and households with children had greater increases in bottled water per capita expenditure and income share (with purchasing prevalence similar in both). Outer island households had greater bottled water expenditure increases for all outcomes compared to households in Tongatapu. There was a mixed pattern across milk expenditure outcomes by household income.

In the sensitivity analysis with post-2016 tax effects removed, the relative changes in bottled water expenditure showed similar patterns by household income but soft drinks expenditure declines were typically greater in high-income than low-income households (Additional File Table 4b). When the quarter after the July 2016 tax increase was compared with the three quarters before; low-income households showed a pattern of greater declines than high-income households in soft drink purchasing prevalence, mean expenditure, food budget share and income share, but lower declines in beverage quantity (not significant, Additional File Tables S5–6).

Discussion

Main findings

Taxed beverages

In 2015/16, there were 5 to 22% decreases in all soft drink expenditure outcomes but not all changes were at a statistically significant level. These decreases were robust to sensitivity analysis that excluded the effects of the 2016 tax increase. They were typically larger than the previously reported decline in SB import volumes in the year after the 2013 SB tax (−10% [18]). Also the reported decreases in expenditure, as a proportion of the 27% tax increase in Tonga, were typically less than the impact of SSB taxes on purchasing or dietary intake in a meta-analysis (average of a 10% decline for a 10% tax) [1] and that reported by recent studies from Berkeley, US [30] and Philadelphia, US [31]. But they were more similar to the proportional impact of SSB taxes on sales in Barbados [32] and Seattle, US [33].

We could not compare volume changes over time, although they can be approximated using Tonga Department of Statistics store price data. From 2010 to 2016 the price of an indicator beverage of 600 ml Coca-Cola increased from T$2.03 to T$2.63 (Tonga Department of Statistics). If we assumed that this was the average price per litre for all soft drinks, then the average decrease in soft drink expenditure volume would have been from 10.0 L to 6.8 L/person/year; which is a greater decline than the expenditure decline (32% vs 22%).

There was a pattern of greater soft drink expenditure declines in low-income households compared to high-income ones, but these results were not statistically significant or robust to sensitivity analysis where the effects of the 2016 tax increase were removed. Despite this, the pattern of greater low-income decline in expenditure is consistent with results from other jurisdictions such as Mexico [7, 34]. Low-income households may respond more than high-income households, because of greater price sensitivity, and as a result of a newly introduced volumetric tax design (per L) which disproportionately increased prices of cheaper taxed products [4].

Untaxed beverages

There were large increases in all bottled water and milk expenditure measures. Substitution to water and other untaxed beverages has also been found by other studies after the introduction of SB taxes [1], but the magnitude of the bottled water expenditure increases seen here for Tonga were much greater. Findings were consistent with large post-tax increases in the levels of water bottling in Tonga [18] and a 2017 household survey that indicated that 23% of respondents switched to bottled water after the SB tax in Tonga [17]. Although positive for health compared to soft drinks, increased purchasing of bottled water might be problematic compared to using rain water that is safe for drinking. This is because both soft drinks and bottled water contribute to litter, use up limited landfill space, and can increase net costs for households. Furthermore, littered containers can provide a breeding site for mosquito vectors of disease [35] such as dengue fever (which causes occasional outbreaks in Tonga).

There was a mixed pattern of bottled water increases by income. Relative increases in per capita expenditure were greater in high-income households (statistically significant), households with children and in the outer islands (although adult only and main island households had the greatest absolute increases in expenditure). Findings suggest that the rapidly growing water bottling industry on the main island has particularly benefited those who can access and afford it. High-income households were fivefold more likely to depend on bottled water as their main drinking water source than low-income households in 2015/16. The drivers of increased bottled water expenditure are likely to do with greater retail availability; however it is unclear why bottled water is increasingly preferred over other water sources, and whether this is affected by concerns about drinking water safety or palatability when it is from household tanks.

Study strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study was the ability to disaggregate changes in expenditure by household age composition, income and island, using two nationally representative surveys and targeting all spending, gifts and food received. Statistical power in these comparisons was limited by survey size. However, it remained important to examine disaggregated patterns because ‘non-significant’ findings can still be useful [36], particularly in domains of major health impact. The study focussed on household reports of soft drink expenditure consumed in the home, bottled water and milk. Juice drinks, cordial and flavoured milk could not be included due to changes in coding between the surveys. Also, there were no data on tap water and beverages consumed outside the home as takeaways, in restaurants or at school. Nevertheless, the effects of takeaway expenditures may be limited given the small 2% increase in reported takeaway food and beverage expenditure during the study period, and the greater increase in high-income households. Expenditure surveys have been found to underestimate expenditure compared to nutrition focussed studies [37], however there was no suggestion that any under-reporting increased over time.

This was an observational study and therefore results are also likely to have been affected by other changes over time such as (eg, macroeconomic changes from commodity price fluctuations or tourism flows). There were some minor changes in household characteristics between surveys, but key expert interviews did not identify any other major policies or programmes that might have influenced SB intake during the study period. Data were not available to compare trends in Tonga with those from a comparable jurisdiction or with pre-existing trends. Furthermore, there was a time lag issue with the 2009 pre-tax change data being collected 4 years before the 2013 tax was implemented.

The lack of price data in this analysis was a limitation. In interpreting expenditure trends, decreasing average soft drink prices (or substitution to cheaper beverages) may have contributed to reduced soft drink expenditure without impacting on the volume consumed [4] and trends may differ by household income. Although, as noted above, the price of an indicator soft drink increased over time, increasing volumes of cheaper SBs imported from Malaysia (Additional File Figure A) may have been more likely to be purchased by low-income households. In 2015/16, the average soft drink price for beverages purchased in low-income households was slightly lower at T$2.60/L than that for high-income households at T$2.90/L (Table 4 and S7), but it is unclear whether this changed since 2009 so any impact on trends by household income are unknown.

Potential implications

SB taxes appeared to be associated with some pro-equity effects in Tonga, particularly in the reduction of soft drink expenditure. However, the equity impacts of SB taxes may be further enhanced through improved policy design. SB taxes should include all SBs to prevent substitution to beverages that might be attractive as cheaper alternatives (such as juice drinks, sachet drinks, cheap imported soft drinks and locally-produced beverages). The Tongan SB excise was broadened to include sugar-sweetened juice and sachet drinks in 2017, but the equity impacts of this change are as yet unknown. Volumetric (per litre) [3] and more recently nutritional taxes (per sugar content) [38], have been recommended to improve the effectiveness of SB taxes, and may increase the relative response from low-income households and purchasers of cheaper beverages [3]. Revenue from the SB tax can be invested back into health or wellbeing [6], for example to ensure availability of safe drinking water (safety of rain water collection tanks or a treated reticulated drinking water supply) for the whole population. This is likely to support healthy beverage substitution and greater equity of SB tax effects; and is particularly important for households that may not be able to afford bottled water, households with children, and in the outer islands. Planned monitoring designed to assess the equity impacts of SB tax changes can inform ongoing health and equity improvements to the policy design. Further research into the socioeconomic patterns of beverage consumption changes in response to SB taxes is needed to further understand equity impacts of SB taxes in different settings.

Conclusions

The sweetened-beverage tax in Tonga was associated with reduced soft drink purchasing and increased bottled water expenditure. Low-income households appeared to benefit from greater relative declines in soft drink expenditure but high-income households appeared to have greater increases in bottled water expenditure.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Pacific Community but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the Pacific Community upon reasonable request and with permission of Tonga Department of Statistics.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIES:

-

Household income and expenditure survey

- NCD:

-

NON-communicable disease

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- SB:

-

sweetened beverage

- SEP:

-

Socioeconomic position

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverage

References

Teng AM, Jones AC, Mizdrak A, Signal L, Genc M, Wilson N. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on purchases and dietary intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1187–204.

Backholer K, Sarink D, Beauchamp A, Keating C, Loh V, Ball K, Martin J, Peeters A. The impact of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages according to socio-economic position: A systematic review of the evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(17):3070–84.

Sharma A, Hauck K, Hollingsworth B, Siciliani L. The Effects of Taxing Sugar-Sweetened Beverages across Different Income Groups. Health Econ. 2014;23(9):1159–84.

Sassi F, Belloni A, Mirelman AJ, Suhrcke M, Thomas A, Salti N, Vellakkal S, Visaruthvong C, Popkin BM, Nugent R. The Lancet Taskforce on NCDs and economics 4: Equity impacts of price policies to promote healthy behaviours. Lancet. 2018;391(10134):2059–70.

Lal A, Mantilla-Herrera AM, Veerman L, Backholer K, Sacks G, Moodie M, Siahpush M, Carter R, Peeters A. Modelled health benefits of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax across different socioeconomic groups in Australia: A cost-effectiveness and equity analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(6):e1002326.

Backholer K, Blake M, Vandevijvere S. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: an update on the year that was 2017. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(18):3219–24.

Colchero MA, Molina M, Guerrero-López CM. After Mexico implemented a tax, purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages decreased and water increased: Difference by place of residence, household composition, and income level. J Nutr. 2017;147(8):1552–7.

Colchero MA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin BM, Ng SW. In Mexico, Evidence Of Sustained Consumer Response Two Years After Implementing A Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):564–71.

Sturm R, Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Soda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children's body mass index. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1052–8.

Caro JC, Corvalan C, Reyes M, Silva A, Popkin B, Taillie LS. Chile's 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax and changes in prices and purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages: An observational study in an urban environment. PLoS Med. 2018;15(7):e1002597.

Nakamura R, Mirelman AJ, Cuadrado C, Silva-Illanes N, Dunstan J, Suhrcke M. Evaluating the 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Chile: An observational study in urban areas. PLoS Med. 2018;15(7):e1002596.

Rodriguez Osiac L, Cofre C, Pizarro T, Mansilla C, Herrera CA, Burrows J, Castillo C. Using evidence-informed policies to tackle overweight and obesity in Chile. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e156.

Alvarez-Sanchez C, Contento I, Jimenez-Aguilar A, Koch P, Gray HL, Guerra LA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Uribe-Carvajal R, Shamah-Levy T. Does the Mexican sugar-sweetened beverage tax have a signaling effect? ENSANUT 2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0199337.

Vall Castello J, Lopez-Casasnovas G. Impact of SSB taxes on consumption. In: CRES-UPF Working Paper #201804–110. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra; 2018.

Mora T, Fichera E, Lopez-Valcarcel BG, Roche D. Do consumers respond to “sin taxes” heterogeneously? New evidence from the tax on sugary drinks using longitudinal scanner data: Research Institute for Evaluation and Public Policies (IRAPP). Barcelona: Universitat Internacional de Catalunya; 2019. p. 1–68.

Government of Tonga: Excise Tax (Amendment) Order 2013: Excise Tax Act 2007. In. Edited by Revenue and Customs. Tonga: Tonga Revenue and Customs; 201. p. 1–8.

World Bank: Using Taxation to Address Noncommunicable Diseases Lessons from Tonga. In. Edited by World Bank. Washington DC: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, TongaHealth, Australian Aid, New Zealand Foreign Affairs and Trade Aid Programme, Government of Japan; 2019: 1–127.

Teng A, Puloka V, Genc M, Filimoehala O, Latu C, Lolomana'ia M, Osornprasop S, Signal L, Wilson N. Sweetened beverage taxes and changes in beverage price, imports and manufacturing: interrupted time series analysis in a middle-income country. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):90.

Sahal Estimé M, Lutz B, Strobel F. Trade as a structural driver of dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in the Pacific: an analysis of household income and expenditure survey data. Glob Health. 2014;10:48.

Andrew McGregor RMB, Manley M, Tubuna S, Deo R. Pacific island food security: situation, challenges and opportunities. Pacific Econ Bull. 2009;24(2):24–42.

Kessaram T, McKenzie J, Girin N, Roth A, Vivili P, Williams G, Hoy D. Noncommunicable diseases and risk factors in adult populations of several Pacific Islands: results from the WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39(4):336–43.

World Health Organization, Ministry of Health Tonga. Global School-based Student Health Survey Tonga 2017 Fact Sheet. In: Global School-based Student Health Survey. Tonga: World Health Organization, Tonga Ministry of Health; 2017. p. 1–5.

Vaipuna T, Smith M, Puloka V, Signal L. Tongan Children’s Beverage Consumption and Availability – New Zealand and Tonga. In: Report Pacific Summer Studentship. Wellington. New Zealand: University of Otago; 2018.

Tonga Statistics Department: Tonga 2016 census of population an housing. Volume 1: Basic tables and administrative report. In. Edited by Kingdom of Tonga, Tonga Health, Tonga Statistics Department, UNICEF, SPC. Nuku’alofa: Tonga Statistics Department; 2017.

Kingdom of Tonga Statistics Department. Pacific Community: Tonga Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2015/2016. Noumea: Pacific Community and Tonga Statistics Department; 2017.

Kingdom of Tonga Statistics Department: Tonga Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2009. 2010.

Government of Tonga: Excise Tax (Amendment) Order 2016: Excise Tax Act 2007. In. Edited by Revenue and Customs. Tonga: Tonga Statistics Department; 2016. p. 1–5.

Daniels S, Glorieux I. Convenience, food and family lives. A socio-typological study of household food expenditures in 21st-century Belgium. Appetite. 2015;94:54–61.

Willan AR, Briggs AH. Statistical analysis of cost-effectiveness data, vol. 37. Great Britain: Wiley; 2006.

Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption 3 Years After the Berkeley, California, Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):637–9.

Roberto CA, Lawman HG, LeVasseur MT, Mitra N, Peterhans A, Herring B, Bleich SN. Association of a Beverage Tax on Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages With Changes in Beverage Prices and Sales at Chain Retailers in a Large Urban Setting. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1799–810.

Alvarado M, Unwin N, Sharp SJ, Hambleton I, Murphy MM, Samuels TA, Suhrcke M, Adams J. Assessing the impact of the Barbados sugar-sweetened beverage tax on beverage sales: an observational study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):13.

Powell LM, Leider J. The Impact of Seattle’s Sweetened Beverage Tax on Beverage Prices and Volume Sold. Econ Hum Biol. 2020;37:100856.

Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. BMJ. 2016;352:1–9.

Vincenti-Gonzalez MF, Grillet ME, Velasco-Salas ZI, Lizarazo EF, Amarista MA, Sierra GM, Comach G, Tami A. Spatial Analysis of Dengue Seroprevalence and Modeling of Transmission Risk Factors in a Dengue Hyperendemic City of Venezuela. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(1):e0005317.

Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature. 2019;567(7748):305–7.

Paterakis SE, Nelson M. A comparison between the National Food Survey and the Family Expenditure Survey food expenditure data. Public Health Nutr. 2007;6(6):571–80.

Grummon AH, Lockwood BB, Taubinsky D, Allcott H. Designing better sugary drink taxes: Tax the sugar, not the liquid. Science. 2019;365(6457):989–90.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ acknowledge Dr. Viliami Fifita, Director of the Department of Statistics in Tonga for facilitating access to the data for this project, Ms. Elisiva Na’ati and Dr. Paula Vivili from the Pacific Community for introducing us to key people and sharing the broader Pacific context, A/Prof James Stanley, statistician for statistical support; Dr. Shuwen Ng for comments on the draft manuscript, and most of all to the many colleagues in Tonga who provided information about the contextual information in Tonga that was crucial for this research.

Funding

This study was supported by the Health Research Council (HRC) of New Zealand (http://www.hrc.govt.nz/, AMT via grant 17/007). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, interpretation or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT, NW, LS, MG formulated the research question, designed the study and acquired research funding. AT analysed the data, produced the tables and figures and wrote the first manuscript draft. NW, LS, MG advised and supervised the research. BB and TL facilitated access to the dataset and gave advice about the structure and quality of the data. VP, TL and CL provided information about the Tonga context. All authors read, edited and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was given by the University of Otago in February 2017 (F17/002) and the Tonga Government awarded a Research Permit for the study on 29 June 2018 (Org 1/8 V.18). Permission to use the datasets was granted by the Government Statistician in Tonga. Anonymised data was provided for data analysis by Pacific Community.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have not competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Further methods, results and discussion. Additional information on the methods, results and discussion from this research study including sensitivity analyses. Please see this file for all additional tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Teng, A., Buffière, B., Genç, M. et al. Equity of expenditure changes associated with a sweetened-beverage tax in Tonga: repeated cross-sectional household surveys. BMC Public Health 21, 149 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10139-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10139-z