Abstract

Background

National Health Service Health Checks were introduced in 2009 to reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks and events. Since then, national evaluations have highlighted the need to maximise the programme’s impact by improving coverage and outputs. To address these challenges it is important to understand the extent to which positive behaviours are influenced across the NHS Health Check pathway and encourage the promotion or minimisation of behavioural facilitators and barriers respectively. This study applied behavioural science frameworks to: i) identify behaviours and actors relevant to uptake, delivery and follow up of NHS Health Checks and influences on these behaviours and; ii) signpost to example intervention content.

Methods

A systematic review of studies reporting behaviours related to NHS Health Check-related behaviours of patients, health care professionals (HCPs) and commissioners. Influences on behaviours were coded using theory-based models: COM-B and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Potential intervention types and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were suggested to target key influences.

Results

We identified 37 studies reporting nine behaviours and influences for eight of these. The most frequently identified influences were physical opportunity including HCPs having space and time to deliver NHS Health Checks and patients having money to adhere to recommendations to change diet and physical activity. Other key influences were motivational, such as beliefs about consequences about the value of NHS Health Checks and behaviour change, and social, such as influences of others on behaviour change. The following techniques are suggested for websites or smartphone apps: Adding objects to the environment, e.g. provide HCPs with electronic schedules to guide timely delivery of Health Checks to target physical opportunity, Social support (unspecified), e.g. include text suggesting patients to ask a colleague to agree in advance to join them in taking the ‘healthy option’ lunch at work; Information about health consequences, e.g. quotes and/or videos from patients talking about the health benefits of changes they have made.

Conclusions

Through the application of behavioural science we identified key behaviours and their influences which informed recommendations for intervention content. To ascertain the extent to which this reflects existing interventions we recommend a review of relevant evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In England in 2017, more than 124,000 people died from cardiovascular disease (CVD).Footnote 1 Changing behaviours related to diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol intake can reduce CVD risk. The delivery of interventions targeting these behaviours also often requires healthcare professional (HCP) behaviours to change.

In 2009, the English National Health Service (NHS) launched ‘NHS Health Check’, a national prevention programme offered to adults 40–74 years old with the aim of helping them reduce their chance of having a heart attack or stroke through behaviour change and, where appropriate, clinical treatment. In brief, eligible patients attending an NHS Health Check will have seven risk factors measured and their 10-year risk of CVD calculated as part of an appointment lasting around 20 min (the majority of which are delivered by healthcare assistants in primary care). During the appointment these results are discussed and the individual is supported to make behaviour changes and/or access clinical treatment to reduce their risk of stroke, kidney disease, heart disease, diabetes or dementia. The programme standards have been developed to guide implementation and delivery of NHS Health Checks [1]. Cost-effectiveness calculations for this programme were based on an assumed uptake of 75% of all those eligible [2]. However, since 2013 when delivery of NHS Health Check became a statutory responsibility of local authorities, < 50% of those eligible have received a NHS Health Check [3]. Improving the effectiveness and uptake of the programme is a key part of PHE’s strategic priority around predictive prevention to better predict and prevent poor health. Interventions are more likely to be effective if they target influences on behaviour [4]. So it needs to be established what the behaviours relevant to NHS Health Checks are, who performs them and the factors influencing these behaviours. To date, research has tended to focused on single populations, e.g. patients or GPs, and specific behaviours, e.g. attending an NHS Health Check. A synthesis of these studies would provide an overarching behavioural picture of those involved in delivery and receipt of NHS Health Checks and so provide the foundations for intervention refinement and development.

Tools such as the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [5], which includes the theoretical model of behaviour COM-B (Fig. 1); the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Fig. 2 shows how the TDF domains are linked to each COM-B component (see Additional file 1 for labels and definitions)) [4, 6] and the Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy (BCTTv1) [7] can be used for identifying influences on behaviours (COM-B and TDF) and providing recommendations for intervention design based on the influences identified (BCW and BCTTv1). The COM-B model, which sits at the ‘hub’ of the BCW, is a simple model to understand behaviour in terms of the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation needed to perform a Behaviour (Fig. 1).

The TDF is used as a framework for synthesising behavioural influences in systematic literature reviews across qualitative and quantitative studies reporting perceived barriers and facilitators of behaviours. These include increasing attendance to diabetic retinopathy screening and triage [8], treatment and transfer of acute stroke patients in emergency care settings [9] and uptake of weight-management programmes in adults at risk of type 2 diabetes [10].

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), a synthesis of 19 frameworks of behaviour change, can be used to characterise interventions. COM-B sits at the ‘hub’ of the Wheel and is surrounded by nine broad types of intervention and seven policy options, i.e. channels through which interventions are implemented (Fig. 2; see Additional file 2 for labels and definitions and Additional file 3 for links between influences on behaviour and potential intervention content.

How intervention functions are delivered can be described using a 93-item taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTTv1) [6]. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) are defined as the active ingredients in interventions designed to bring about change. The Theory and Techniques Tool (https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/ - see Additional file 4) articulates the strength of evidence between BCTs and their hypothesised mechanisms of action.

The aims of this study were to identify:

-

1.

groups of people (actors) and their behaviours that are relevant to increasing uptake and follow up of NHS Health Checks within primary care and community and/or social care, representing these in a conceptual, ‘systems’ map.

-

2.

influences on the behaviours identified and categorise them using two theoretical models: COM-B and TDF.

-

3.

types of intervention and component behaviour change techniques (BCTs) likely to change these influences.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

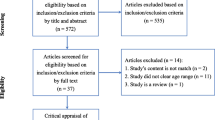

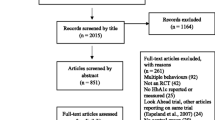

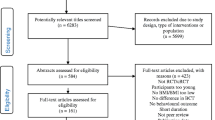

We conducted a systematic review in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Electronic databases Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO were searched for publications reporting barriers to and facilitators of behaviours relevant to uptake and follow up of the NHS Health Check. We included empirical qualitative and/or quantitative research and systematic review articles of behaviours and of barriers to and facilitators of behaviours relevant to NHS Health Checks. We included all papers with title and abstract written in English. Searches were limited to 2008 - December 2018 as this corresponded to the introduction of NHS Health Checks. The full search strategy is provided in Additional file 5.

Stakeholder consultation

We assembled a panel of stakeholder experts to suggest relevant literature not identified by the electronic searches.

Study selection and quality assessment

Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two researchers. For selected abstracts and those where there was uncertainty at first screening, full papers were screened against the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any papers for which the decision was not clear were discussed with other members of the review group. We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [11] to assess quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies (Additional file 6).

Data extraction tools

Study characteristics extracted were: setting; participant; target behaviour; how the target behaviour was measured and barriers and facilitators to the target behaviour. Quotes and author interpretations of barriers and facilitators were coded using COM-B and TDF.

Data analysis

We conducted a six-step framework [12] and thematic [13] analysis to synthesise and explain influences on NHS Health Check related behaviours identified in the systematic review:

-

i)

Framework analysis by deductively coding extracted data on barriers/facilitators into the COM-B and TDF domain(s) they were judged to best represent.

-

ii)

Thematic analysis within each domain, grouping similar data points and inductively generating summary theme labels.

-

iii)

Recording the frequency of each theme, i.e. how many studies each theme was identified in.

-

iv)

Classifying each theme as either barrier, facilitator, or both.

-

v)

Classifying each domain as either barrier (all identified themes within that domain are barriers), facilitator (all identified themes within that domain are facilitators) or both (if themes within the domain are a combination of barriers and facilitators).

-

vi)

Selecting key themes within domains using: i) established criteria - frequency (number of studies), elaboration (number of themes) and evidence of conflicting beliefs within domains (e.g. if some participants report lack of knowledge of guidelines whereas others report familiarity with guidelines) [14]; ii) PHE stakeholder input to identify strategic priority areas to target.

TDF provides a greater level of detail than COM-B and was used primarily to classify influences on behaviours.

Using the Behaviour Change Wheel, based on COM-B and TDF coded influences on behaviours, we signposted to functions interventions might serve [15] and BCTs to deliver those functions [16]. The following steps were taken to translate the list of potentially relevant BCTs into the recommendations for intervention design and refinement:

-

i)

Stakeholders with relevant perspectives on the delivery of these BCTs selected BCTs for a prototype intervention.To permit a systematic approach to selecting which BCTs are appropriate to each context, the APEASE criteria [13] were used. These form a checklist of considerations when selecting intervention content and mode of delivery, i.e. is it Affordable - can it be delivered to budget?; Practicable - can it be delivered to scale?; Effective/Cost-effective - is there evidence it is likely to be (cost)effective?; Acceptable - is it acceptable to those delivering, receiving and commissioning it?; are there any Side-effects/Safety issues?; will it increase Equity, i.e. does it disadvantage any groups? See Additional file 7.

-

ii)

Having produced a prototype intervention, further feedback (again guided by the APEASE criteria) was obtained from a wider group of stakeholders including HCPs (GPs, practice nurses, practice managers and commissioners) and patients (NHS Health Check attenders and non-attenders).

Results

Thirty-seven studies met the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 3). The majority were conducted in primary care (n = 28) and collected data from patients (n = 25). Table 1 provides a summary of the setting, participants and behaviours investigated. Study quality details are presented in Additional file 6.

Table 2 describes the setting, participants, behaviour and data collection method for individual studies.

Systems map of NHS health check behaviours

Behaviours reported in the systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of NHS Health Check-related behaviours are provided in the behavioural systems map Fig. 4. Studies identified in the systematic review typically focussed on barriers to and facilitators of HCPs delivering NHS Health Checks (n = 18 studies), patients attending NHS Health Checks (n = 16 studies) and patients changing behaviour following NHS Health Checks (n = 15 studies). The map is divided into behaviours occurring at five sequential time periods: i) HCPs inviting patients to attend NHS Health Checks; ii) patients attending NHS Health Checks; iii) HCPs delivering NHS Health Checks; HCPs recording NHS Health Check data; service managers and/or commissioners synthesising and disseminating NHS Health Check data; iv) patients attending specialist referral; v) patient changing CVD risk-related behaviours; patients attending repeat NHS Health Check.

Barriers to and facilitators of NHS health check behaviours

Domains and themes identified as relevant to each NHS Health Check behaviour is provided in Table 3. Barriers, facilitators or both barriers and facilitators for each behaviour is summarised in Table 4.

Key barriers to and facilitators of NHS health check behaviours

Domains and themes identified as key in influencing NHS Heath Check behaviours are summarised for each behaviour below and in Fig. 5 and Table 5 along with illustrative examples.

-

1.

HCPs inviting patients to attend NHS Health Checks. Domains related to this behaviour were identified in four studies. The key domain was ‘environmental context and resources.’ The key theme within this domain was: Difficulty identifying eligible patients from records as a barrier to issuing invitations.

-

2.

Patients attending NHS Health Checks. Domains related to this behaviour were identified in 16 studies. Five key domains were identified:

-

i.

‘Knowledge’ - a lack of understanding of CVD risk and purpose of NHS Health Checks – coded as a barrier.

-

ii.

‘Environmental context and resources’ – i) timing and location of NHS Health Checks influenced attendance (some perceived timing and location to be convenient, others did not); ii) conducting NHS Health Checks in pharmacies. Both themes were coded as both barriers and facilitators.

-

iii.

‘Social influences’ – i) having a family history of illness was coded as both a barrier and facilitator as it discouraged some from attending and encouraged others to attend; ii) the impact of interactions with GP with which they did not have a good relationship and being told to change was coded as a barrier.

-

iv.

‘Beliefs about consequences’ – i) There were a range of views on the extent to which NHS Health Checks were perceived as beneficial for early detection, this was coded as both barrier and facilitator reflecting opposing views within this theme; ii) NHS Health Checks provided the opportunity to be proactive about health - this was coded as a facilitator.

-

v.

‘Emotion’ – i) anxiety at receiving high risk result; ii) reassurance as a motivation to attend. Both themes were coded as facilitators as anxiety and reassurance encouraged attendance.

-

i.

-

3.

HCPs delivering NHS Health Checks. Nine key domains were identified across 18 studies:

-

i.

‘Knowledge’ – i) HCPs perceptions of patients understanding of CVD risk was coded as both barrier and facilitator as some HCPs considered that patients understood their risk, but this view was not shared by all; ii) HCPs lack of familiarity with guidelines and associated tools which was coded as a barrier.

-

ii.

‘Cognitive and interpersonal skills’ - HCPs perceived the need for i) training to deliver behavioural support and, ii) to communicate risk. The former was coded as both barrier and facilitator as some but not all perceived the need for training to improve behavioural support skills, the latter was coded as a barrier as all reported the need to improve risk communication skills.

-

iii.

‘Memory, attention and decision processes’ - HCPs had different views on whether behavioural intervention should be offered before pharmacological intervention to reduce CVD risk so this was coded as a both a barrier and facilitator.

-

iv.

‘Environmental context and resources’ – i) availability of resources and time to deliver NHS Health Checks was coded as both barrier and facilitator reflecting different access to resources and different amounts of time to deliver NHS Health Checks; ii) lack of appropriate space to deliver NHS Health Checks was coded as a barrier; iii) having computer systems which support delivery of NHS Health Checks was coded as both barrier and facilitator.

-

v.

‘Social influences’ – taking account of patients’ social context when providing behavioural support was coded as both barrier and facilitator as some but not all HCPs considered patients’ social context.

-

vi.

‘Social/professional role and identity’ – i) some but not all HCPs thought there was role clarity within teams when delivering NHS Health Checks, so this was coded as a barrier and facilitator; ii) all pharmacy staff reported that delivering NHS Health Checks positively promoted diversification of their professional role so this was coded as a facilitator.

-

vii.

‘Beliefs about consequences’ – i) holding the belief that NHS Health Checks are beneficial in terms of preventive healthcare; ii) believing appropriately framing messages is important. Both themes were coded as both barrier and facilitator reflecting opposing beliefs within each theme.

-

viii.

‘Beliefs about capabilities’ - HCPs varied in their level of confidence to discuss and initiate behaviour change in patients, so this was coded as both a barrier and facilitator.

-

ix.

‘Optimism’ - HCPs are varyingly optimistic about whether patients will change their behaviour after the NHS Health Check, this was coded as both a barrier and facilitator.

-

i.

-

4.

HCP referral to specialist service. The key domain, ‘environmental context and resources’ was identified in three studies and contained the theme, lack of funded services to refer patients to. This was coded as a barrier.

-

5.

Patients attending specialist referral. One key domain, ‘beliefs about consequences’ was identified in one study and contained the theme, holding the belief that regular attendance at referral appointments would help to reduce CVD risk. This was coded as a facilitator.

-

6.

Patients changing CVD risk-related behaviours. Eight key domains were identified across 15 studies:

-

i.

‘Knowledge’ - Patients’ understanding of CVD risk was coded as both barrier and facilitator as some HCPs considered that patients understood their risk, but this view was not shared by all.

-

ii.

‘Environmental context and resources’ – i) time and cost as a barrier to patients changing behaviours related to CVD risk - this was coded as both barrier and facilitator as some reported not having time or funds to change behaviour whilst others reported sufficient time and funds; ii) HCPs perceived there to be greater adherence to behavioural support when CVD risk was communicated using electronic calculators than paper risk charts – this was coded as a facilitator

-

iii.

‘Social influences’ – support from family and friends was reported by patients as a facilitator of behaviour change to reduce CVD risk.

-

iv.

‘Social/professional role and identity’ – Patients perceived the role of the HCP to influence their engagement with changing behaviour to reduce CVD risk, as there were differing views of which role would most effectively encourage patients to change (e.g., GPs, practice nurses, community HCPs) this was coded as both barrier and facilitator.

-

v.

‘Beliefs about capabilities’ – Patients reported the belief that they were able to change their behaviour to reduce CVD risk if changes were small and sustainable – this was coded as a facilitator.

-

vi.

‘Beliefs about consequences’ – i) patients reported contradictory guidelines on healthy behaviours was a barrier to behaviour change; ii) related to the previous theme, patients often reported inaccurate beliefs of what constitutes a healthy behaviour, e.g. binge drinking was not harmful if done infrequently – this was coded as a barrier.

-

vii.

‘Intentions’ – Patients reported different views on whether the NHS Health Check was a ‘wake-up call’ to change their behaviour – this was coded as both a barrier and facilitator.

-

viii.

‘Optimism’ – Patients’ fatalistic beliefs about their health (i.e. there was nothing they could do to change whether they would experience a cardiovascular event) was a barrier to change.

-

i.

-

7.

Patients attending repeat NHS Health Check. One key domain was identified in one study. The domain ‘Intentions’ contained the theme – intention to attend a future NHS Health Check. This was coded as a facilitator as, where it was discussed, patients reported the intention to attend a repeat check.

-

8.

HCPs recording NHS Health Check data. One key domain was identified across two studies. ‘Environmental context and resources’ – HCPs reported that multiple methods of invitation to NHS Health Checks was a barrier to accuracy of reporting relevant data.

Signposting to relevant intervention content

Intervention content (intervention types, policy categories and BCTs) which is theoretically linked to identified influences on NHS Health Check behaviours which could be considered for inclusion in intervention design and refinement is suggested in Table 6. Example suggestions for how BCTs could be delivered to target key barriers to and facilitators of NHS Health Check behaviours are provided in Table 7.

Discussion

We identified nine behaviours related to NHS Health Checks and barriers to and facilitators of eight of these behaviours): i) HCPs inviting patients to attend NHS Health Checks - It can be time consuming identifying eligible patients; ii) patients attending NHS Health Checks - Family history of illness, the need to reduce anxiety and be reassured may increase attendance. Since patients need to perceive the NHS Health Check as relevant to them, this may be facilitated by patients understanding the purpose of NHS Health Checks as an opportunity to be proactive about CVD.; iii) HCPs delivering NHS Health Checks - HCPs perceive the need for more training (risk communication and behaviour change) and time and appropriate space to deliver NHS Health Checks. HCPs disagree on the extent to which NHS Health Checks were beneficial to patients and whether offering behavioural before pharmacological intervention was appropriate. Taking account of patients’ social context and appropriate message framing are perceived as important but do not always happen. HCPs had varying levels of confidence to deliver behavioural support.; iv) HCPs refer patients to a specialist service - Lack of availability of relevant services hinder onward referral; v) patients attending specialist referral - Patients believe it is important to attend appointments regularly; vi) patients changing CVD risk-related behaviours - NHS Health Checks can serve as a ‘wake-up call’ to change. However, patients vary in their understanding of CVD risk following NHS Health Check and some are not aware of the behaviours which can influence CVD risk. The influence of family and friends in supporting change is perceived as important and HCP role can influence change differentially. Fatalistic beliefs in health can hinder change as can contradictory guidelines. Patients welcome small, incremental changes to behaviour.; vii) patients attending repeat NHS Health Check - Most patients intend to attend a repeat NHS Health Check; viii) HCPs recording NHS Health Check data - Recording relevant data can be hindered where multiple invitation methods are used; ix) service managers and/or commissioners synthesising and disseminating NHS Health Check data (no barriers or facilitators were identified in relation to this behaviour).

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to apply theoretical models to studies focussing solely on influences on NHS Health Check behaviours and to make theory-based recommendations for intervention design. Shaw et al. 2016 [54] used the TDF to understand NHS Health Check-related behaviours in a review but included UK and non-UK CVD risk reduction programmes.

Implications for service commissioners and providers are to audit current provision against the behaviours, barriers and facilitators identified in this study. This would provide foundations in ensuring the programme remains fit for purpose for the next 10 years and beyond. Implications for commissioners are that they should maximise opportunities to ensure that the purpose of NHS Health Checks as a prevention programme is clear to eligible patients in promotional materials, provide digital records structured to easily identify eligible patients and record programme data. Implications for HCPs providing NHS Health Checks are that they should offer flexible appointment times where possible, invest in training for frontline staff to provide behavioural support for patients and ensure that the benefits of NHS Health Checks are conveyed to staff.

It should be noted that the review is only as comprehensive as the studies it includes, and these have not all taken a comprehensive approach to investigating barriers and facilitators, i.e. they may present a partial picture of influences on behaviours. Our review findings may therefore reflect an absence of evidence (i.e. a TDF domain reported as not relevant to a behaviour may be because it was not investigated) rather than an evidence of absence (a TDF domain was investigated and found not to be relevant to a behaviour). It should also be noted that the recommendations flowing from our findings reflect the types of interventons that we would expect on theoretical grounds to be effective, and this is not a review of effectiveness of interventions; that would also be a useful study.

Such a study could investigate the extent to which interventions to promote NHS Health Check behaviours target the barriers and facilitators identified in this review. This work would identify any missed opportunities for intervention and inform intervention design and refinement. Interventions (both nationally and locally implemented) to promote NHS Health Check behaviours could be described in terms of function and channels through which interventions are delivered using the frameworks of BCW and BCTTv1. This would include describing interventons in terms of their service provision such as pharmacy and apps and local outreach; communication and marketing in NHS Choices and NHS Health Check invitation letters; regulation and legislation for the NHS Health Check programme; and guidelines for delivery of the NHS Health Check appointment.

A further study that would add to this evidence is a consensus study of experts in the various relevant areas to ascertain the extent to which they agree with the findings from the literature, to identiy gaps and to elaborate with likely ranges of effective application of each proposed intervention.

The NHS Health Check programme has seen 6.7 million people aged 40 to 74 benefit from a check over the past 5 years. This study identifies key influencers of behaviour which impact on the success of the programme based on a systematic review that was strengthened by coding of extracted data into behavioural frameworks and formation of a detailed underpinning user journey and Theory of Change for the NHS Health Check programme. Based on this rigorous analysis, it makes specific, evidence-informed recommendations for commissioners, which should be considered as part of the forthcoming NHS Health Check review in order to ensure the programme is implemented as effectively as possible for the next 10 years and beyond [55].

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first attempt to apply the behavioural science frameworks, BCW, TDF and BCTTv1 to understand influences on NHS Health Check behaviours and systematically identify likely effective interventions and component techniques that could be either incorporated into existing interventions or form the basis of designing new interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

British Heart Foundation (www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/research/heart-statistics/bhf-cvd-statistics%2D%2D-uk-factsheet.pdf)

Abbreviations

- BCT:

-

Behaviour change technique

- BCTTv1:

-

Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy v1

- BCW:

-

Behaviour Change Wheel

- COM-B:

-

Capability Opportunity Motivation – Behaviour

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- PHE:

-

Public Health England

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Public Health England. NHS Health Check programme standards: a framework for quality improvement. 2014. https://www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/commissioners-and-providers/delivery/quality-assurance/. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

Public Health England. Uptake and retention in group-based weight-management services: Literature review and behavioural analysis. 2018. www.gov.uk/government/publications/uptake-and-retention-in-group-based-weight-management-services. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

Martin A, Saunders CL, Harte E, Griffin SJ, MacLure C, Mant J, et al. Delivery and impact of the NHS health check in the first 8 years: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(672):e449–e59.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived Behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660–80.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Graham-Rowe E, Lorencatto F, Lawrenson JG, Burr JM, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, et al. Barriers to and enablers of diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: a systematic review of published and grey literature. Diabet Med. 2018;35(10):1308–19.

Craig LE, McInnes E, Taylor N, Grimley R, Cadilhac DA, Considine J, et al. Identifying the barriers and enablers for a triage, treatment, and transfer clinical intervention to manage acute stroke patients in the emergency department: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework (TDF). Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):157.

England PH. Uptake and retention in group-based weight-management services: literature review and behavioural analysis. London; 2018.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, Boardman F, Gagnon MP, Rousseau MC. Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Montreal: Department of Family Medicine, McGill University; 2011. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/FrontPage.

Srivastava A, Thompson S. Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research. J Adm Gov. 2009;4(2). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Data_Integrity_Notice.cfm?abid=2760705. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O'Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel - a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Johnston M, Naomi Carey R, Connell Bohlen L, Johnston D, Rothman A, Bruin M, et al. Linking behavior change techniques and mechanisms of action: Triangulation of findings from literature synthesis and expert consensus, 2018.

Alageel S, Gulliford MC, McDermott L, Wright AJ. Implementing multiple health behaviour change interventions for cardiovascular risk reduction in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):171.

Baker C, Loughren EA, Crone D, Kallfa N. Patients' perceptions of a NHS health check in the primary care setting. Qual Prim Care. 2014;22(5):232–7.

Boase S, Mason D, Sutton S, Cohn S. Tinkering and tailoring individual consultations: how practice nurses try to make cardiovascular risk communication meaningful. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(17–18):2590–8.

Chatterjee R, Chapman T, Brannan MG, Varney J. GPs' knowledge, use, and confidence in national physical activity and health guidelines and tools: a questionnaire-based survey of general practice in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(663):e668–e75.

Cook EJ, Sharp C, Randhawa G, Guppy A, Gangotra R, Cox J. Who uses NHS health checks? Investigating the impact of ethnicity and gender and method of invitation on uptake of NHS health checks. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:13.

Dalton AR, Bottle A, Okoro C, Majeed A, Millett C. Uptake of the NHS health checks programme in a deprived, culturally diverse setting: cross-sectional study. J Public Health. 2011;33(3):422–9.

Ellis N, Gidlow C, Cowap L, Randall J, Iqbal Z, Kumar J. A qualitative investigation of non-response in NHS health checks. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):14.

Greaves C, Gillison F, Stathi A, Bennett P, Reddy P, Dunbar J, et al. Waste the waist: a pilot randomised controlled trial of a primary care based intervention to support lifestyle change in people with high cardiovascular risk. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:1.

Honey S, Bryant LD, Murray J, Hill K, House A. Differences in the perceived role of the healthcare provider in delivering vascular health checks: a Q methodology study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:172.

Honey S, Hill K, Murray J, Craigs C, House A. Patients' responses to the communication of vascular risk in primary care: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(1):61–70.

Ismail H, Atkin K. The NHS health check programme: insights from a qualitative study of patients. Health Expect. 2016;19(2):345–55.

Ismail H, Kelly S. Lessons learned from England's health checks Programme: using qualitative research to identify and share best practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:144.

Jenkinson CE, Asprey A, Clark CE, Richards SH. Patients' willingness to attend the NHS cardiovascular health checks in primary care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:33.

Kirby M, Machen I. Impact on clinical practice of the joint British Societies' cardiovascular risk assessment tools. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(12):1683–92.

Krska J, du Plessis R, Chellaswamy H. Implementation of NHS health checks in general practice: variation in delivery between practices and practitioners. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17(4):385–92.

Krska J, du Plessis R, Chellaswamy H. Views of practice managers and general practitioners on implementing NHS health checks. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17(2):198–205.

McDermott L, Wright AJ, Cornelius V, Burgess C, Forster AS, Ashworth M, et al. Enhanced invitation methods and uptake of health checks in primary care: randomised controlled trial and cohort study using electronic health records. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(84):1–92.

McNaughton RJ, Shucksmith J. Reasons for (non)compliance with intervention following identification of 'high-risk' status in the NHS health check programme. J Public Health. 2015;37(2):218–25.

Murray KA, Murphy DJ, Clements SJ, Brown A, Connolly SB. Comparison of uptake and predictors of adherence in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in a community-based cardiovascular prevention programme (MyAction Westminster). J Public Health. 2014;36(4):644–50.

Riley R, Coghill N, Montgomery A, Feder G, Horwood J. Experiences of patients and healthcare professionals of NHS cardiovascular health checks: a qualitative study. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):543–51.

Riley VA, Gidlow C, Ellis NJ. Uptake of NHS health check: issues in monitoring. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018:1–4.

Robson J, Dostal I, Madurasinghe V, Sheikh A, Hull S, Boomla K, et al. NHS health check comorbidity and management: an observational matched study in primary care.[erratum appears in Br J Gen Pract. 2017 Mar;67(656):112; PMID: 28232346]. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(655):e86–93.

Burgess C, Wright AJ, Forster AS, Dodhia H, Miller J, Fuller F, et al. Influences on individuals’ decisions to take up the offer of a health check: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2437–48.

Chipchase L, Waterall J, Hill P. Understanding how the NHS health check works in practice. Pract Nurs. 2013;24(1):24–9.

Shaw RL, Lowe H, Holland C, Pattison H, Cooke R. GPs' perspectives on managing the NHS health check in primary care: a qualitative evaluation of implementation in one area of England. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e010951.

Shaw RL, Pattison HM, Holland C, Cooke R. Be SMART: examining the experience of implementing the NHS health check in UK primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:1.

Attwood S, Morton K, Sutton S. Exploring equity in uptake of the NHS health check and a nested physical activity intervention trial. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):560–8.

Artac M, Dalton ARH, Babu H, Bates S, Millett C, Majeed A. Primary care and population factors associated with NHS health check coverage: a national cross-sectional study. J Public Health. 2013;35(3):431–9.

Usher-Smith JA, Harte E, MacLure C, Martin A, Saunders CL, Meads C, et al. Patient experience of NHS health checks: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e017169.

Mills K, Harte E, Martin A, MacLure C, Griffin SJ, Mant J, et al. Views of commissioners, managers and healthcare professionals on the NHS health check programme: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018606.

Mason A, Liu D, Marks L, Davis H, Hunter D, Jehu LM, et al. Local authority commissioning of NHS health checks: a regression analysis of the first three years. Health Policy. 2018;122(9):1035–42.

McNaughton RJ, Oswald NT, Shucksmith JS, Heywood PJ, Watson PS. Making a success of providing NHS health checks in community pharmacies across the Tees Valley: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:222.

Penn L, Rodrigues A, Haste A, Marques MM, Budig K, Sainsbury K, et al. NHS diabetes prevention Programme in England: formative evaluation of the programme in early phase implementation. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019467.

Perry C, Thurston M, Alford S, Cushing J, Panter L. The NHS health check programme in England: a qualitative study. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(1):106–15.

Roberts DJ, de Souza VC. A venue-based analysis of the reach of a targeted outreach service to deliver opportunistic community NHS health checks to 'hard-to-reach' groups. Public Health. 2016;137:176–81.

Taylor J, Krska J, Mackridge A. A community pharmacy-based cardiovascular screening service: views of service users and the public. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(5):277–84.

Visram S, Carr SM, Geddes L. Can lay health trainers increase uptake of NHS health checks in hard-to-reach populations? A mixed-method pilot evaluation. J Public Health. 2015;37(2):226–33.

Shaw RL, Holland C, Pattison HM, Cooke R. Patients' perceptions and experiences of cardiovascular disease and diabetes prevention programmes: a systematic review and framework synthesis using the theoretical domains framework. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:192–203.

Department of Health and Social Care. Advancing our health: Prevention in the 2020s - consultation document. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s-consultationdocument. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Centre for Behaviour Change Research Associate Silje Zinc for her assistance in screening papers.

Funding

This project was funded by Public Health England who employ project authors CS, TC and KT. LA, FL and SM were funded via an academic honorary contract covered by a Collaborative Academic Research and Activity Agreement where Public Health England reimbursed University College London for LA, FL and SM’s time. CS, TC and KT conceived the study and contributed to revisions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS, TC and KT conceived the study. LA, FL and SM designed the study. LA collected the data. LA and FL analysed the data. LA, FL and SM interpreted the results. LA drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CS, TC and KT are employed by project funders, Public Health England.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

COM-B and TDF labels.

Additional file 2:.

BCW labels.

Additional file 3:.

BCW matrices.

Additional file 4:.

BCT TDF matrix.

Additional file 5:.

Search terms.

Additional file 6:.

MMAT study quality.

Additional file 7:.

APEASE criteria.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Atkins, L., Stefanidou, C., Chadborn, T. et al. Influences on NHS Health Check behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 20, 1359 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09365-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09365-2