Abstract

Background

Immunization is a cost-effective public health strategy. Immunization averts nearly three million deaths annually but immunization coverage is low in some countries and some regions within countries. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to assess pooled immunization coverage in Ethiopia.

Method

A systematic search was done from PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, HINARI, and SCOPUS, WHO’s Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), African Journals Online databases, grey literature and reviewing reference lists of already identified articles. A checklist from the Joanna Briggs Institute was used for appraisal. The I2 was used to assess heterogeneity among studies. Funnel plot were used to assess publication bias. A random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of immunization among 12–23 month old children using STATA 13 software.

Result

Twenty eight articles were included in the meta-analysis with a total sample size of 20,048 children (12–23 months old). The pooled prevalence of immunization among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia was found to be 47% (95%, CI: 46.0, 47.0). A subgroup analysis by region indicated the lowest proportion of immunized children in the Afar region, 21% (95%, CI: 18.0, 24.0) and the highest in the Amhara region, 89% (95%, CI: 85.0, 92.0).

Conclusion

Nearly 50% of 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia were fully vaccinated according to this systematic review and meta-analysis this indicates that the coverage, is still low with a clear disparity among regions. Our finding suggests the need for mobile and outreach immunization services for hard to reach areas, especially pastoral and semi-pastoral regions. In addition, more research may be needed to get more representative data for all regions.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020166787.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Immunization is one of the cost-effective public health interventions, and can be used to limit life threatening childhood illnesses like diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis virus, measles, mumps, pneumonia, polio virus and rotavirus [1, 2].

Worldwide Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) was launched in 1974 to all WHO members with the aim of strengthening routine immunization coverage and decreasing Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPDs). In Ethiopia routine immunization was started in 1980 with a purpose of reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality [3,4,5].

Globally, immunization averts 2–3 million deaths yearly, but VPDs still accounts worldwide for over 2 million under five deaths annually, the majority of them being from countries in sub-Saharan Africa [6].

A 2017 WHO report revealed that, 116.2 million infants (85%) received a third dose of DPT globally, only 123 (63%) of 194 countries achieved three doses of DPT coverage ≥90% [7,8,9].

A 2018 WHO report found 13.5 million infants had never received any dose of vaccine, and 19.4 million never received the third dose of DPT. Among all children who were under and unimmunized, 11.7 million lived in just ten countries one of which is Ethiopia [10].

At present, vaccination is being given on static, outreach and mobile basis [11]. Ethiopia follows WHO recommended immunization schedule. Infants should receive vaccination in 1 year after birth with: one dose bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) and oral polio vaccine is given at birth or as soon as possible; three doses of OPV, three doses of Penta-valent, three doses pneumococcal vaccines, two doses of rotavirus are given at interval of 4 weeks duration at the 6th, 10th and 14th weeks, 9 month first dose of measles [11]. The second dose of measles vaccine was launched and integrated to the routine immunization in the year of 2019 and which was provided to 15- month old children [12].

Of these vaccines, the third dose of DPT (DPT 3) is often used as a measure of immunization system performance. Instead of DPT, some countries use a Penta-valent vaccine, which includes (Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Heamophilus influence type B and Hepatitis B) [11].

The government has shown strong commitment to improving EPI access and utilization by training nearly four thousand health extension workers and setting up 15,000 health posts which have integrated community case management in 2010 [11, 13]. It is also endorsing sustainable development goal target 3.2 which is aimed at reducing preventable deaths of newborns and under-five children by 2030 [14].

Despite increased trend of immunization coverage in the last decades [15, 16], the most common VPDs that substantially result in under-five morbidity and mortality are pneumonia, diarrhea and measles [17, 18]. Pneumonia is a leading single killer of under-five children [19]. It is estimated that 3,370,000 children encounter pneumonia annually in Ethiopia which contributes to 18% of all causes of deaths and claiming over 40,000 under-five children every year [17]. Diarrhea is the second leading cause of under-five mortality with an estimated 1.7 million cases of diarrhea annually [19]. Morbidity reports and community-based studies indicated diarrheal disease is still public health problem [20,21,22]. Likewise, measles is one of the public health problems with an incidence of 50 cases/1,000,000 population per year which is above the national target for measles elimination by 2020 (1 < cases /1,000,000 population per year). The estimated case fatality is between 3 and 6% but this rate is underestimated because of incomplete reporting of measles [12].

In Ethiopia, all health delivery services are decentralized in to 11 self-administering regions and two city administrations. They provide healthcare services from Zonal to Keble level (the smallest administrative unit) they get vaccines as per their request from EPSA (Ethiopia Pharmaceutical Supply Agency) which is an autonomous agency of FMoH with responsibility of policy, direction setting and vaccine distribution with support of UNICEF for forecasting, procurement, and overall technical support with adequate vaccine supply [23].

The cold chain system is highly sensitive to any kind of mishandling and power interruption. FMoH and partners implemented and endorsed cold chain rehabilitation plan, regular cascade training of cold chain technicians, national cold chain inventory and installing solar fridge for hard to reach area were done but still there is no published articles for cold chain at all level [23, 24].

Numerous studies revealed that rural residence, government employer, female household head, parents having formal education of primary and above, antenatal care follow up, giving birth at health facility, good knowledge about immunization benefit and schedule, short distance to health facility, having four or more family size can increase vaccine coverage contrary to fear of side effects, low wealth status, being too busy, lack of awareness about vaccination, poor perception toward vaccination, were predictors of child immunization [7, 25,26,27,28].

Understanding the extent of vaccine coverage and its associated factors are important for designing strategies that can reduce the burden of vaccine preventable diseases. There is no systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia on immunization coverage among children 12–23 month old. Therefore, aims of this was to pool and synthesize recent evidence on the prevalence of vaccine coverage among 12–23 months old children using small fragmented regional studies to pool and form national result to consolidate available data and determine current prevalence of vaccine coverage in Ethiopia.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with international prospective register and systematic reviews PROSPERO (2020 CRD42020166787) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020166787.

Search strategy and appraisal of studies

All published studies conducted in Ethiopia reporting the fully vaccinated or immunization coverage from September 2009 to 2019 were included. The search was limited to English language, human and cross-sectional studies. This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA) checklist guideline [29]. The electronic databases searched were PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, HINARI, SCOPUS, WHO’s Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), and African Journals Online databases. In addition to that, articles were also searched through a review of the grey literature available on local universities repository and by reviewing the reference lists of already identified articles. The key terms used for the database searches were connected by Boolean operators in our search below Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) and combined as follows: “Epidemiologic” OR “Child” OR “Children” AND “Coverage, Vaccination” OR “Vaccination coverages” OR “Immunization Coverage” OR “Coverage, Immunization” OR “coverage’s, Immunization” OR “Immunization coverage” AND “Ethiopia” Filters: Free full text; Publication date from 2009/01/01 to 2019/12/31; Humans Sort by: [pubsolr12]. The searched articles were publication from 01/01/2009 to 01/11/2019.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

Study area: only those studies conducted in Ethiopia were considered as included studies.

Participants/population: Children 12–23 month old were included.

Intervention: Immunization for eligible children (< 2 year).

Comparison: those immunized and those who were unimmunized.

Study design: observational studies (cross-sectional were included).

All English-language, full-text articles conducted in Ethiopia, published from January 2009 to September 2019, in peer-reviewed journals or grey literature was eligible for inclusion criteria.

Exclusion

Studies that did not report specific outcomes for immunization coverage quantitatively, age of children greater than 24 month old and study design other than cross-sectional study were excluded.

Outcome measurement

Primary outcome of this study was prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia. It was measured as the number of children who were fully immunized divided by the total number of children in studies multiplied by 100.

Case definition of fully immunized children is when they have received one dose of Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), three doses of DPT, three doses of polio vaccines and one dose of measles vaccination by the age of 9–12 months [11]. All studies that reported the vaccination coverage in children aged 12–23 month were eligible for inclusion.

Data abstraction procedure

Two authors (TY and AM) independently extracted data using Joanna Briggs Institute data extraction tool for applied cross-sectional study design. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus reached through third person (KHA). Outcome data extraction format contains author, publication year, region, sample size, study design, response rate, and prevalence with 95% confidence interval. Retrieved articles were evaluated based on their title, objective and methodology. At this stage, irrelevant articles were excluded and the full texts of the remainder articles were reviewed for inclusion criteria. Articles that fulfilled the prior criteria were used as a source of data for the final analysis.

The database search results were exported

Duplicate articles were removed using EndNote software (version X7; Thomson Reuters, New York, NY). Two independent reviewers critically appraised each individual article using the quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies before analysis which was included representation, sampling, random selection, non-response rate, data collection, case definition, reliability and validity of study tool, method of data collection, prevalence,numerator and denominator was assessed for quality summary [30]. It was categorized as having low risk of bias “yes” high risk of bias “no” if the score is 8–10 we consider it as having “low risk of bias” 6–7 score “moderate risk of bias” 0–5 score “high risk of bias”(Table 1) (below).

Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion and reaching consensus including a third reviewer. The average of two independent reviewer’s quality scores were used to determine whether the articles should be included. Articles with methodological errors or incomplete reporting of results with no full text were excluded from the final analysis.

Statistical analysis

The aim of this review was to assess pooled prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia.

Information on the studies characteristics such as publication year, study region, study design, sample size, non-respondent and immunization coverage were extracted from each study using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet template. Then, data were exported to Stata (version 13; Stata Corp, College Station, TX) for further analysis.

A random effect model was used to estimate pooled prevalence of fully vaccinated children with 95% confidence interval (CI) in Ethiopia. Funnel plot asymmetry was used to check for publication bias (Fig. 4). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I-squared (I2) statistics and the cutoffs of 25, 50, 75% was used to declare heterogeneity as low, moderate and high respectively [54]. Subgroup analysis was also conducted to detect prevalence of immunization coverage and heterogeneity among regional states of the country.

Operational definitions

Pastoralist and semi-pastoralist: means communities, located in some part of Benishangul Gumuz, Gambella, Oromia, Somali, and Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ region [51].

Fully vaccinated: when children receive one dose of Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), three doses of DPT, three doses of polio vaccines, and one dose of measles vaccination by the age of 9–12 months [11].

Result

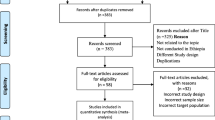

In the first step of our search, 363 articles were retrieved from immunization coverage among children aged 12–23 months using different electronic databases were searched: like PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, HINARI, Web of Science, SCOPUS, WHO’s Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), and African Journals Online databases. 22 articles were excluded due to duplication, from remaining 341 articles 308 articles were excluded as they were not related to the topic, not done in Ethiopia and study design. Only 35 full text articles were accessed and assessed for their eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Finally 28 articles were eligible and included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1) (below).

Characteristics of included studies

All retained twenty eight studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia were cross-sectional study; twenty five of them were conducted from eight regional states and three national surveys, a total sample size of 20,048 children aged 12–23 months were included. The minimum sample size was 173 [41] and maximum sample size was 2004 [16]. Nin (32.1%) of studies were from Amhara region [31, 33,34,35, 37, 42, 44, 47, 49], six (21.4%) from South Nation Nationality and People’s region [8, 27, 38, 41, 48, 52], four (14.3%) from Oromia region [32, 36, 39, 43], were three (10.7%) survey nationwide [15, 16, 55], two (7.1%) from pastoral and semi-pastoral area of the country [50, 51], lastly one (3.6%) from Somali state [40] and one (3.6%) from Tigrai regional states [25]. All studies were published in peer review journals. Fully vaccinated criteria were based on maternal recall; immunization card and BCG scar.

An estimated over all pooled prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia was 47% (95% CI: 46.0, 047.0). The lowest proportion included studies was 21% (95%,CI:18.0,24.0) [45] and the highest 89% (95%,CI:85.0,92.0) [33]. The I-square test showed that there was no heterogeneity among included studies (I2 = 0.00, p-value < 0.005). Studies with largest weight were EDHS 2016 [16], EDHS 2011 [53] and Mebrahtom and Birhane [46] 9.99,9.62,7.65 respectively. While those with smallest weight were from Facha wolde [48], Porth et al. [52] and Gualu and Dillie [33] respectively 1.05, 1.16 and 1.44 (Table 2) (below). Using random effect model analysis the pooled prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23 moths in Ethiopia showed (I2 = 0.000, p-value< 0.005) (Fig. 2) (below).

Subgroup analysis

We have conducted subgroup analysis based on regional states of the country, Tigrei region had highest prevalence of immunization coverage of 12–23 months children 77% (95% CI: 74.0,81.0) followed by Amhara region 71% (95% CI: 70.0,72.0), SNNP 60% (95% CI: 58.0,62.0), Oromia region 41% (95% CI: 41.0,42.0), Somali region, 37% (95% CI: 33.0,41.0) and A far region had the smallest immunization coverage in Ethiopia 12% (95% CI: 10.0,13.0). In subgroup analysis Amhara region had the highest weight 26.06 the possible reason may be high number of studies done and included in that area and lowest weight was Somali region 2.90 (Fig. 3) (below).

Publication bias

In the present study there was no publication bias because studies were equally distributed within funnel plot, and visual inspection was resembled symmetrical (Fig. 4) (below).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current meta-analysis is first of its kind for immunization coverage among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia.

The government is still struggling to achieve its target of immunization coverage despite difficulties in implementing different strategies and approaches. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we assessed pooled prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23 month old children in Ethiopia.

Over all pooled prevalence of immunization coverage was 47.0% (95% CI: 46.0, 47.1). pooled prevalence is lower than the WHO 2018 factsheet report of 86% [10]. Similarly, it is lower than DHS reports of Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMIC), such as Kenya (67.2%) [56], Cameroon (62.5%) [57], Ghana (77.0%) [58], Tanzania (75.3%) [59], India (62%) [60], Philippines (70.0%) [61], Bangladesh (82%) [62], Zimbabwe (76.0%) [63] and South Africa (61.0%) [64]. In addition to that, this meta-analysis is also lower than HMIS (Health Management Information System) report of 88% and government target of health sector transformation plan-IV (HSTP) which is 93% [65].

Interestingly, the current work is in line with other DHS reports of Madagascar (49.1%) [66] and Uganda (55.8%) [67]. However, it is higher than DHS report and pooled prevalence of immunization coverage and associated factors which has been done in Nigeria were 31.0% [68] and 34.4% (CI: 27.0, 41.9) respectively [69]. We found regional variation in immunization coverage among 12–23-month children in Ethiopia. The lowest prevalence was observed from Afar region 12.0% (95% CI: 10.0, 13.0) while the highest was Amhara region that was 71% (95% CI: 70.1, 72.0).

There is variation among regional states of the country both Agrarian and pastoralists regions. The possible reason for high immunization coverage of some regions particularly agrarian communities may be they can easily have access to immunization service, have relatively better infrastructure, good socio-economic status, high literacy rate, access to information [70, 71]. The other reason may be women’s decision making, women who had medium wealth status and above, short distance to the health facility, good knowledge about complication during pregnancy, good perception toward immunization were positive contributing elements of immunization coverage [72,73,74].

On the other hand, regions that had low immunization coverage according to this finding were more likely to be pastoralists and semi-pastoral regions of the country accordance with evidences from EDHS 2011,2016 and mini 2019 [15, 16, 53]. Possible reason for low immunization coverage may be 82.12% of populations who are living in rural area face difficulties in having access to health services delivery this problem result in high mortality rate among under-fives particularly under-immunized and unimmunized children that is attributed to immunization [75].

Other problems include weak infrastructure, limited distribution and poor quality services such problem hindered access to health facility [76].

Still there are challenges that need special consideration particularly in pastoral and semi-pastoral regions of Ethiopia when it comes to routine immunization during planning programs. Special strategies and approaches are needed to ensure to have access and proper utilization of immunization services.

Limitation

Despite carefully extensive search and planned reviews which were done, and more than two reviewers involved in minimizing all possible risk of bias, our study is not without limitation. Some of the limitations include the fact that we have reviewed only cross-sectional studies which are prone to confounding the number of studies which were not equally distributed among regional states. Only English language articles were synthesized, some articles were published in emerging journals, and numbers of studies included in the current study were very few and may affect the overall result.

Conclusion

The current work found that pooled prevalence of immunization coverage among 12–23-month old children was very low compared to both international and national immunization coverage prevalence. Therefore, we recommend government to strength mobile and outreach immunization services for hard to reach and under developed pastoral and semi-pastoral regions. Secondly, we recommend integrating both human and animal health services provision due to the nature of the pastoral and semi pastoral communities. Thirdly; we recommend integrating immunization service in non-governmental health facilities since they account for 11% of health coverage of the country but hardly provide free immunization service. Lastly, future research should be considered for all states of the country that may reveal more about prevalence of immunization coverage and factors affecting immunization coverage should be synthesized.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset for this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette Guerin

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DHS:

-

Demographic Health Survey

- DPT:

-

Diphtheria Pertussis Tetanus

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey

- EPI:

-

Expanded Program of Immunization

- HMIS:

-

Health Management Information System

- IRIS:

-

Institutional Repository for Information Sharing

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle Income Countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews And Meta-Analysis

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- VPDs:

-

Vaccine Preventable Diseases

- WHO:

-

World Health organization

References

Wondwossen L, et al. Advances in the control of vaccine preventable diseases in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27(Suppl 2):1.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia’s health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13(3):46–9.

Ababa A. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia ministry of health. Ethiopia: Postnatal Care; 2003.

Okwo-Bele J-M, Cherian T. The expanded programme on immunization: a lasting legacy of smallpox eradication. Vaccine. 2011;29:D74–9.

Wiysonge CS, et al. A bibliometric analysis of childhood immunization research productivity in Africa since the onset of the expanded program on immunization in 1974. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):66.

World Health Organization. RSV vaccine research and development technology roadmap: priority activities for development, testing, licensure and global use of RSV vaccines, with a specific focus on the medical need for young children in low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals CH-1211; 2017.

Tamirat KS, Sisay MM. Full immunization coverage and its associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in Ethiopia: further analysis from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1019.

Hailu S, et al. Low immunization coverage in Wonago district, southern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220144.

Wang H, et al. GBD 2015 child mortality collaborators. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1725–74.

Organization, W.H. Expanded programme on immunization (EPI) factsheet 2019: Indonesia; 2019.

FMOH. Ethiopia National Expanded Programme on Immunization, comprehensive multi-year plan 2016–2020. Addis Ababa: Federal ministry of health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2015.

WHO. Ethiopia launches measles vaccine second dose (MCV2) introduction: over 3.3 million children will receive the vaccine annually; 2019. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/ethiopia-launches-measles-vaccine-second-dose-mcv2-introduction-over-33-million-children-will.

Bilal NK, et al. Health extension workers in Ethiopia: improved access and coverage for the rural poor. Yes Africa Can: Success Stiroes from a Dynamic Continent; 2011. p. 433–43.

Miller NP, et al. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):424–34.

Indicators K. Mini Demographic and health survey; 2019.

CSA, I., Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA; 2016.

Walker CLF, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16.

Diouf K, et al. Diarrhoea prevalence in children under five years of age in rural Burundi: an assessment of social and behavioural factors at the household level. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):24895.

Organization, W.H. Children: reducing mortality. Fact Sheet. 2016; 2017. [cited 2020 May 5]; Available from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=World+Health+Organization%3A+Children%3A+reducing+mortality+fact+sheet+2017&btnG.

World Health Organization. World health statistics 2013: a wealth of information on global public health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–40.

Hashi A, Kumie A, Gasana J. Prevalence of diarrhoea and associated factors among under-five children in Jigjiga District, Somali region, eastern Ethiopia. Open J Prev Med. 2016;6(10):233–46.

Ethiopia Federal Minister of Health. National expanded programme on immunization, comprehensive multi year plan 2011-2015. Addis Ababa; 2010.

FMOH. An Unfinished Journey: vaccine supply chain transformation in Ethiopia; 2019.

Girmay A, Dadi AF. Full immunization coverage and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in a hard-to-reach areas of Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2019;2019:1924941.

Boulton ML, et al. Vaccination timeliness among newborns and infants in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212408.

Tefera YA, et al. Predictors and barriers to full vaccination among children in Ethiopia. Vaccines. 2018;6(2):22.

Okeibunor JC, et al. Polio eradication in the African region on course despite public health emergencies. Vaccine. 2017;35(9):1202–6.

Moher D, L. A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097.

Hoy D, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–9.

Animaw W, et al. Expanded program of immunization coverage and associated factors among children age 12-23 months in Arba Minch town and Zuria District, southern Ethiopia, 2013. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:464.

Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12-23 months in ambo Woreda, Central Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:566.

Gualu T, Dilie A. Vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in debre markos town, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Adv Publ Health. 2017;2017.

Kassahun MB, Biks GA, Teferra AS. Level of immunization coverage and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in lay Armachiho District, North Gondar zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:239.

Lake M, et al. Factors for low routine immunization performance; a community based cross sectional study in Dessie town, south Wollo zone, Ethiopia, 2014. Adv Appl Sci. 2016;1:7–17.

Legesse E, Dechasa W. An assessment of child immunization coverage and its determinants in Sinana District, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:31.

Mekonnen AG, Bayleyegn AD, Ayele ET. Immunization coverage of 12–23 months old children and its associated factors in Minjar-Shenkora district, Ethiopia: a community-based study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):198.

Meleko A, Geremew M, Birhanu F. Assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors with full vaccination among children aged 12-23 months at Mizan Aman town, bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2017;2017:7976587.

Mohammed H, Atomsa A. Assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors in Oromia regional state, eastern Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2013;2(1):36–41.

Mohamud AN, et al. Immunization coverage of 12-23 months old children and associated factors in Jigjiga District, Somali National Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:865.

Fite RO, Hailu LD. Immunization coverage of 12 to 23 months old children in Ethiopia; 2019.

Tesfaye TD, Temesgen WA, Kasa AS. Vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Northwest Ethiopia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(10):2348–54.

Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Childhood vaccination in rural southwestern Ethiopia: the nexus with demographic factors and women's autonomy. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17 Suppl 1:9.

Yismaw AE, et al. Incomplete childhood vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in Gondar city administration, northwest, Ethiopia 2018. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):241.

Beyene EZ, et al. Factors associated with immunization coverage among children age 12-23 months: the case of zone 3, Afar regional state, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2013;51(SUPPL. 1):41–50.

Mebrahtom S, Birhane Y. Magnitude and determinants of childhood vaccination among pastoral community in Amibara District, Afar regional state, Ethiopia. Res J Med Sci Pub Health. 2013;1(3):22–35.

Debie A, Taye B. Assessment of fully vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Mecha District, north West Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Sci J Public Health. 2014;2(4):342–8.

Facha W. Fully vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12 to 23 months in Arba Minch Zuriya Woreda, Southern Ethiopia. J Pharm Altern Med. 2015;7:19–25.

Ebrahim T, Beyene W. Childhood immunization coverage in tehulederie district, northeast of Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Int J Curr Res. 2015;7(9):20234–40.

Tessema F, et al. Child vaccination coverage and dropout rates in pastoral and semi-pastoral regions in Ethiopia: CORE Group polio project implementation areas. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2019;33.

Kidanne L, et al. Child vaccination timing, intervals and missed opportunities in pastoral and semi-pastoral areas in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2019;33.

Porth JM, et al. Childhood immunization in Ethiopia: accuracy of maternal recall compared to vaccination cards. Vaccines. 2019;7(2):48.

ICF, C., Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and health survey; 2011.

Huedo-Medina TB, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193.

Demographic E. Health survey 2011 central statistical agency Addis Ababa. Maryland: Ethiopia ICF International Calverton; 2012.

Demographic K. Health survey 2014: key indicators. Kenya National Bureau of statistics (KNBS) and ICF macro; 2014.

EDSM V. Enquête démographique et de Santé au Mali 2012–2013. Disponiblecnom.sante.gov.ml/docs/FR286.pdf (accès le 06/04/2018 à 20H 18) P. 2013;252:290.

GHSGDPI, G.S.S Ghana Demographic and health survey 2014. Key Indicators; 2015.

Demographic, T. Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey, 2015–2016. Dar es Salaam and Rockville: Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (Dar es Salaam), Ministry of Health (Zanzibar), National Bureau of Statistics (Dar es Salaam), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (Zanzibar), ICF; 2016.

Sciences, I.I.f.P. and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

Authority PS. Philippines National Demographic and health survey 2017: key Indicators. Quezon City and Rockville; 2018.

Research, N.I.o.P, et al. Bangladesh demographic and health survey: National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT); 2011.

Agency, Z.N.S. and I. International. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 2015. Rockville: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) ICF International; 2016.

National Department of Health , S.S.A., South African Medical Research Council , and ICF. South Africa Demographic and health survey 2016: key indicators. South Africa and Rockville: NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC and ICF Pretoria; 2017.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. HSTP Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16–2019/20 (2008‐2012 EFY). Addis Ababa; 2015.

Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT) et ICF Macro. 2010. Enquête Démographique et de Santé de Madagascar 2008-2009. Antananarivo, adagascar : INSTAT et ICF Macro.

Statistics, U.B.o. and ICF. Uganda demographic and health survey 2016: key indicators report. Rockville: UBOS; 2017.

Commission, N.P., and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and health survey 2013. Abuja: National Population Commission and ICF International; 2014; 2018.

Adeloye D, et al. Coverage and determinants of childhood immunization in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2017;35(22):2871–81.

Farzad F, et al. Socio-economic and demographic determinants of full immunization among children of 12-23 months in Afghanistan. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2017;79(2):179–88.

Ahmed S, et al. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11190.

Kifle MM, et al. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):22.

Kohi TW, et al. When, where and who? Accessing health facility delivery care from the perspective of women and men in Tanzania: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):564.

Yaya S, et al. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a comparative study between Ethiopia and Nigeria. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196896.

Woldemichael A, et al. Availability and inequality in accessibility of health Centre-based primary healthcare in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213896.

Chaya N. Poor access to health services: ways Ethiopia is overcoming it. Res Comment. 2007;2(2):1–6.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank collage of medicine and health science staffs for their support. They also would like to express appreciation to DHS forum for their guidance on EDHS data extraction.

Funding

This meta-analysis does not have any funding agencies in government or non-government organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TY conceived the study, study selection, preparation of protocol, searching strategy for literature, participated data analyzes, interpretation and manuscript preparation. AM and OM involved in developing protocol, searching strategy, critical appraisal, data extraction and draft of manuscript, KH prepared and supported, final draft of manuscript. All authors (TY, AM, OM and KH) involved all steps read and approved final draft of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares there was no competing of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nour, T.Y., Farah, A.M., Ali, O.M. et al. Immunization coverage in Ethiopia among 12–23 month old children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 20, 1134 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09118-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09118-1