Abstract

Background

Diet-related cardiovascular diseases have produced a large health burden in China. Coal miners are a high-risk population for cardiovascular disease, but there is little evidence concerning associations between coal miners’ dietary patterns and their 10-year cardiovascular disease risk score levels.

Methods

The study included 2632 participants and focused on dietary patterns associated with higher 10-year cardiovascular disease risk score levels. A valid semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to collect data regarding dietary intake, and dietary patterns were identified using factor analysis combined with cluster analysis. Logistic regression was used to assess associations between dietary patterns and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk score levels.

Results

For ground workers, compared with the ‘Healthy’ pattern, the ‘High-salt’ and ‘Refined grains’ patterns were significantly associated with higher 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score level (OR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.02–2.21; OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.26–2.93) and 10-year ischemic cardiovascular disease risk score level (OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.25–3.80; OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.48–4.72) adjusted for gender, and behavioural and socioeconomic factors. The ‘High-fat and salt’ pattern was significantly associated with higher 10-year ischemic cardiovascular disease risk score level (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.13–3.42). For underground workers, the ‘High-salt’ pattern was significantly associated with higher 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score level (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.16–2.36) and 10-year ischemic cardiovascular disease risk score level (OR: 1.76, 95% CI: 1.09–2.84).

Conclusions

This study provides evidence for dietary patterns associated with higher 10-year cardiovascular disease risk score levels in Chinese miners, and facilitates relevant departments in designing effective dietary guidelines to ameliorate dietary structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Currently, cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for about one-third of all deaths worldwide [1]. In China, CVD is the leading cause of death and disease burden [2,3,4], and two out of five deaths are attributed to CVD [3]. The mortality, incidence, and prevalence of diet-related CVD have been increasing over the past 30 years, and now the number of CVD patients has reached 290 million [3]. Among CVDs, atherosclerosis cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) have remained at a high prevalence, and ischemic cardiovascular diseases (ICVD) have produced large health burden [2, 5]. Each CVD is undesirable for maintaining a healthy population, and previous studies have shown that coal mining areas have higher CVD risk and mortality than non-coal mining areas [6,7,8], so to improve the primary prevention of CVD, coal miners’ health should be taken seriously.

In recent years, the global food system and food supply have been shifting rapidly [9]. The Chinese diet used to be characterized by coarse grains, but now it has been transformed into a dietary structure based on refined carbohydrates [10]. At the same time, because of improvements in living conditions, consumption of meat in the diet has increased significantly [11, 12]. Dietary habits play a key role in CVD primordial prevention [13], and a diet high in fat or refined foods is clearly not conducive to the control or prevention of CVD [14]. Coal miners are characterized by lower socioeconomic status and education levels compared to the general population, and for these reasons, coal miners are more likely to have poor eating habits [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the suboptimal diet of coal miners for CVD prevention. Current evidence on the impact of coal miners’ dietary pattern on CVD is scant. Therefore, this study focused on the dietary patterns associated with 10-year CVD risk score levels, so it may offer potential benefits for primary prevention of CVD in miners by identifying suboptimal diets, and facilitate relevant departments in designing effective dietary guidelines.

Considering the potential influence of work environment [16, 17], this study stratified the participants based on workplace and identified the dietary patterns associated with higher 10-year CVD risk score levels, including 10-year ASCVD and ICVD risk score levels, separately.

Methods

Study population

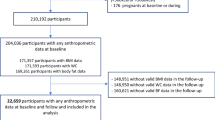

Participants were drawn from The TONGMEI study, which was designed to investigate coal miners’ health status and was conducted in 2013 in Shanxi Province in China. This study enrolled 3265 people aged between 35 and 65 years old. Of these, 30 people with self-reported cardiovascular events, 104 people with insufficient data about baseline information, 274 people with missing data about one or more variables of diet required in the analysis, and 225 people with abnormal values of diet or physical activity information identified by relative guidelines, were excluded from the analysis [18]. Therefore, the current analyses were based on data from 2632 people. The sampling of the TONGMEI study, a cross-sectional study, has been described in detail elsewhere [19]. A flowchart presents the analytical sample, excluding ineligible individuals (Fig. 1).

Assessment of general information and covariates

Data on general information including marital status, education level, monthly income, work type, alcohol consumption, and family history of illness were collected using a self-administered baseline questionnaire. In addition, the physical activity level was assessed by the international physical activity questionnaire including work-related activity, housework activity, leisure, transport-related activity, exercise, sitting posture, and sleeping time. Details on the collection of blood samples and measurement of anthropometrics indicators have been previously published [19]. The blood pressure (BP) of participants was categorized into Normal (systolic BP (SBP) < 120 mmHg and diastolic BP (DBP) < 80 mmHg), Elevated (SBP ≥ 120 mmHg or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg), and Hypertension (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mm) [20]. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight divided by the square of height. Alcohol users were defined as those consuming alcohol at least once per month in the past year [21]. Smokers were defined as those smoking at least one cigarette per day during the past month [22]. The workplace of miners was divided into ground and underground; ground workers engaged in coal transportation, operation management, communication, power supply, and some office jobs. Underground workers mainly engaged in machinery driving, reserves, and some auxiliary jobs.

Cardiovascular risk score levels

The 10-year CVD risk scores include 10-year ICVD and ASCVD risk scores, which are effective tools with good performance for 10-year CVD risk prediction among the Chinese population [23]. Meanwhile, 10-year CVD risk scores were recommended for application in CVD screening by the Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases [24, 25]. The 10-year CVD risk scores were calculated by the specific risk evaluation models, further converted into absolute risk (%), and graded into risk levels according to the relevant guidelines. The 10-year ASCVD risk was defined as the probability of developing the first ASCVD event over a 10-year period among people free from ASCVD at the beginning [26]. The 10-year ASCVD risk score was calculated by the sex-specific evaluation figure of ASCVD risk developed by the Joint Committee of Dyslipidemia Management [27]; the risk factors included in evaluation models were age, BP, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, current smoking status, and diabetes. In additions, four risk levels were determined according to the guideline: Low risk (< 5%), Medium risk (5–9%), High risk (10–19%), and Extremely high risk (≥20%) [27].

The 10-year ICVD risk was defined as the probability of developing the first ICVD event over a 10-year period among people free from ICVD at the beginning [24]. The 10-year ICVD risk score was calculated using a sex-specific evaluation sheet published by the Chinese Society of Cardiology of the Chinese Medical Association [24], and updated based on a previous study [28]; the risk factors included in evaluation models were age, SBP, BMI, TC, current smoking status, and diabetes. Additionally, the following three risk levels were determined: Extremely low risk (≤5%), Low risk (5–10%), and Medium-high risk (≥10%) [24].

Dietary assessment

Dietary data were collected from the semi-quantitative FFQ [19]. All of the risk factors and FFQ were collected in the same year. To minimize participants’ recall bias as much as possible, this study made a commitment to provide each participant with a health report to increase their motivation to answer accurately, and provided uniform metrics of food consumption and different portions of foods for reference by participants at the survey site. Food items consumed frequently in the population were categorized into 20 categories including rice, wheat flour, cereal, tubers(e.g. white potatoes), fried dough, pork, red meat, poultry, viscera, fish and shrimp, dairy products, beans and bean products, egg and egg dishes, vegetables, pickled vegetables, salted and preserved vegetables, vermicelli, pastry, fruits, and nuts [19]. Participants were asked to recall the portion size, frequency, and cycle of 20 food categories for the past year. The traditional Chinese unit Liang was used to measure the portion size, participants were helped to estimate sizes accurately, and finally converted to grams (e.g. 1 Liang = 50 g). Information on the cycle of consumption for each food category was collected by using five categories (never, daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly). Finally, the mean intake in grams/day of each food category was assessed based on portion size, frequency, and cycle.

Dietary pattern identification

Dietary patterns were derived by an exploratory approach of factor analysis combined with cluster analysis, a method that has been widely used in the construction of dietary patterns [29, 30]. Factor analysis identified food groups that were frequently consumed together. Four factors were retained in ground and underground workers, by combining with the Akaike information criterion value, Schwarz Bayesian criterion value (which produces fewer factors with less significance) [31], scree test, and eigenvalues. Foods with factor loading ≥0.2 were retained after varimax rotation, while foods with factor loading ≥0.35 were considered highly important to each factor [32]. Participants were assigned a factor score computed for detecting the actual underlying and unobservable factor [33]; meanwhile, the factor scores were used in the cluster analysis after being standardized.

The number and cluster seeds of clusters were determined through hierarchical cluster analysis, and the final clusters (patterns) were identified by K-means cluster analysis. All participants were assigned to one of the clusters (patterns), and the descriptive names were assigned for each pattern according to the cluster means of factors scores that contributed relatively highly [34].

Statistical analyses

This study stratified the participants based on the workplace and identified the dietary patterns, separately. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the association of each risk score level with demographic and lifestyle variables.

The dietary patterns of workers in the two workplaces were generated by factor analysis combined with cluster analysis. Each participant received a factor score by factor analysis implemented in SAS PROC FACTOR, and the factor scores were standardized prior to the cluster analysis. Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted to identify the most appropriate number and the cluster seeds for the subsequent K-means cluster analysis. Thereafter, the construction of final dietary patterns using K-means cluster analysis performed by SAS PROC FASTCLUS [34].

Logistic regression was used to assess the association between dietary patterns and the 10-year CVD risk score levels. The 10-year CVD risk score level was the dependent variable, the dietary patterns were the independent variables, and dummy variables were calculated in the regression models. We fitted three models by adjusting for potential confounding effects. Model 1 included the dietary pattern. In model 2, besides the primary variable of interest, we further adjusted for gender and drinking status (No/Yes). In model 3, we further adjusted for education level (Bachelor degree or above, Junior college and senior high school, Junior high school or below), monthly income (≤4000, 4000–6000, 6000–8000, ≥8000), marital status (married, others), physical activity level (Inactive, Minimally Active, Health-enhancing physical activity), and family history (No/Yes). Among the three models, we did not adjust for age, smoking status, and blood pressure, because these covariates were included in the outcome measure.

We conducted sensitivity analysis to observe the impact of missing data of dietary intake on dietary patterns, imputed the missing data of dietary intake in the imputed dataset, the maximum-likelihood estimates via EM algorithm were computed for the missing data [35], performed by SAS PROC MI. In sensitivity analysis, we rebuilt dietary patterns in the same way, and examined the stability of dietary patterns. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.) and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The main analyses set was based on 2632 participants aged 35–65 with no CVD events. The descriptive statistics of the demographic factors and their association with the 10-year CVD risk score levels are shown in Table 1. For 10-year ASCVD risk score level, one participant aged 65 was excluded because the 10-year ASCVD risk evaluation model was developed for adults aged 35–64. The remaining participants were classified into four levels: Low risk (N = 1753, 66.6%), Medium risk (N = 551, 20.9%), High risk (N = 259, 9.8%), and Extremely high risk (N = 68, 2.6%). For 10-year ICVD risk score level, participants were classified into three levels: Extremely low risk (N = 2222, 84.4%), Low risk (N = 326, 12.4%), and Medium-high risk (N = 84, 3.2%).

Dietary patterns

The factor loadings derived from factor analysis are presented in Table 2. Among the ground workers, four factors were derived, explaining 36% of the total variance in consumption of the foods. The first factor included red meat, poultry, viscera, fish and shrimp, pork, fried dough, and pastry. The second factor included tubers, wheat flour, beans and bean products, vegetables, pastry, vermicelli, cereal, and eggs and egg dishes. The third factor included fried dough, salted and preserved vegetables, pickled vegetables, and vermicelli. The fourth factor included fish and shrimp, beans and bean products, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, nuts, rice, cereal, and eggs and egg dishes.

Participants were given a factor score after factor analysis, and assigned to each of the patterns after the cluster analysis. The final dietary patterns were identified by K-means cluster analysis, and are presented in Table 3. Each pattern was labeled according to the cluster means of factor scores, which were relatively high; the high mean factor scores of each pattern are underlined in Table 3. Among the ground workers, the first pattern with a high mean factor score was on the fourth factor, characterized by high intakes of fruits, dairy products, nuts, rice, cereal, eggs and egg dishes, and called ‘Healthy’. A pattern with a high mean factor score on the third factor, characterized by high intake of salted and preserved vegetables, pickled vegetables, and vermicelli was called ‘High-salt’. The other cluster patterns, respectively, were named ‘High-fat and salt’ and ‘Refined grains’ in the same way.

Among the underground workers, four factors were derived, explaining 34% of the total variance in the consumption of the foods (Table 2). Dietary pattern included four patterns, namely ‘Healthy’, ‘High-salt’, ‘High-fat’ and ‘Northern’ patterns (Table 3). Compared to the ‘Healthy’ pattern, the ‘High-salt’ pattern had a high score on the fourth factor and primarily consisted of salted and preserved vegetables and pickled vegetables. The other patterns, were named ‘High-fat’ and ‘Northern’ in the same way.

In both ground and underground workers, dietary patterns included four sets of patterns. In the following regression analysis, the dietary patterns were the independent variables and the dummy variables were calculated. Compared to the other patterns, the ‘Healthy’ pattern primarily consisted of healthier foods, and served as the reference group for exploring the association of three other suboptimal patterns with 10-year CVD risk score levels.

Dietary patterns and distributions of sample characteristics

Participants with a ‘High-salt’ pattern were the major group and constituted 31.9% of the ground workers (Additional file 1: Table S1). Meanwhile, the local special suboptimal pattern was characterized by the ‘High-salt’pattern, which was also identified in the underground workers. In addition, participants with a ‘High-fat’ pattern were the major group, and constituted 31.1% of the underground workers (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Dietary patterns and 10-year CVD risk score levels

For all logistic regression analyses, the ‘Healthy’ patterns were served as the reference group both in ground and underground workers. After adjusting for all covariates, among the ground workers, the ‘High-salt’ pattern (OR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.02–2.21) and ‘Refined grains’ pattern (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.26–2.93) were significantly associated with higher 10-year ASCVD risk score levels after adjusting for all covariates. Among the underground workers, the ‘High-salt’ pattern was significantly associated with higher 10-year ASCVD risk score levels (OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.16–2.36) (Table 4), and the association was still statistically significant in sensitivity analyses (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Among the ground workers, compared with the ‘Healthy’ pattern, the ‘High-fat and salt’ pattern (OR: 1.97; 95% CI: 1.13–3.42), ‘High-salt’ pattern (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.25–3.80), and ‘Refined grains’ pattern (OR: 2.64; 95% CI: 1.48–4.72) were significantly associated with higher 10-year ICVD risk score levels. Among the underground workers, the ‘High-salt’ pattern was significantly associated with higher 10-year ICVD risk score levels (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.09–2.84), whereas neither the ‘Northern’ (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.78–1.85) and ‘High-fat’ patterns (OR: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.72–1.73) showed a significant association with 10-year ICVD risk score levels in the adjusted analysis (Table 5). In sensitivity analysis, nearly all dietary patterns were still significantly associated with higher 10-year ICVD risk score levels, except for the ‘High-fat and salt’ pattern (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Discussion

In previous studies, more attention was paid to coal miners’ occupational injuries and other poor health status [36, 37], but little evidence concerning coal miners’ CVDs has been reported. Previous research showed that coal mining areas are associated with poorer health status and higher incidence of CVD [38, 39], so primary prevention for coal miners should be taken seriously. Dietary habits are recognized as a key modifiable factor in CVD prevention [40]. Given the complexity of diet, there may be stronger effects on health of overall diet than any single component [40]. Therefore, research focused on single foods or nutrients related to coal miners’ health is not enough [41, 42], and it is important to study not only individual foods or nutrients, but also the effects of the entire diet [14].

This study focused on the whole dietary pattern associated with 10-year CVD risk score levels and presented different dietary patterns in ground and underground workers, the dietary differences may due to social networks or work pressure [43]. The majority of coal miners in this study had extremely low and low cardiovascular risk score levels, but low risk does not mean no risk. To prevent CVD risk from developing from low to high, more attention should be given to CVD prevention.

Three suboptimal diets associated with higher 10-year CVD risk score levels were identified in this study. The local special suboptimal pattern was ‘High-salt’ characterized by salted and preserved vegetables and pickled vegetables. A positive association was found between the ‘High-salt’ pattern and 10-year ASCVD risk score levels both in ground and underground workers, and the odds ratios were 1.50 (95% CI: 1.02–2.21) and 1.65 (95% CI: 1.16–2.36), respectively. The ‘High-salt’ pattern was also associated with higher 10-year ICVD risk score levels. This finding is consistent with evidence that a salt-rich diet is related to cardiovascular events in non-coal mining areas [44, 45]. However, there are differences in the food combinations of diets in different populations. Compared with salt-rich diets in Western countries, the ‘High-salt’ pattern identified in this study was mainly characterized by salted and preserved vegetables and pickled vegetables, not manufactured foods [46]. A high salt intake is not conducive to blood pressure control, and is positively related to CVD [44], which is consistent with our finding. Because of the sociocultural factors, a ‘High-salt’ pattern remains pervasive in Chinese diets, and was also identified in the Henan Rural Cohort Study of China [47]. Although dietary salt intake has shown a downward trend in recent years, it is still more than twice the recommended amount (China: < 6 g/day, WHO: < 5 g/day) [3]. Given Chinese taste preferences, specific strategies should be designed to improve their dietary structure to prevent CVD, alternative techniques of food cooking should be advanced instead of pickling, and it is essential to find alternatives to replace salt in cooking, reduce dietary salt intake, and retain the nutrients in foods [3, 48].

Chinese traditional diets used to be dominated by coarse food grains (e.g. maize, sorghum, etc.), and now are loaded highly with refined grains (e.g. white rice, wheat flour, etc.) [12]. The shift in dietary pattern is clearly detrimental to CVD prevention. Poor-quality carbohydrates are associated with CVD risk [10]. As the results showed, the ‘refined grains’ pattern, characterized by wheat flour, pastry, and other starch-rich foods, was positively associated with 10-year ASCVD (OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.26–2.93) and 10-year ICVD risk score level (OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.48–4.72). Refined food diets have also been identified in northern of China [49], and even in other Asian countries, refined food diets related to CVD risk have also been reported [50]. Currently, refined foods account for a large portion of global dietary patterns. In the United States, nearly three in four Americans consume too many refined foods, such as white bread and corn flakes instead of white rice and pastry [14, 51]. Refined foods have similar metabolic characteristics as high-starch vegetables (e.g. white potatoes), and can be digested rapidly without a fiber-rich structure [14]. Whether it is white bread in Western diets or pastry in Chinese diets, all of these will produce brisk rises in blood glucose and induce multiple adverse manifestations associated with cardiovascular events [52,53,54]. Consequently, reducing refined grain consumption in the diet for cardiovascular health are major dietary priorities, based on their adverse effects and prevalence in modern diets [14].

The association between a high-fat diet characterized by high intake of meats and CVD risk is complicated, as the category and ingredients of the meats have effects on CVD risk, such as sodium and heme iron [14]. Fanelli et al. found that ‘Western’ diets along with meats and sandwiches, in African-Americans were associated with higher 10-year ASCVD risk [26]. Among the underground workers, like the ‘Northern’ pattern, the ‘High-fat’ pattern had high factor loadings, not only on meats, but also on vegetables and beans. That may explain why there was no significant association between these diets and 10-year CVD risk score levels. Although there are many controversies, it has been established that certain foods, including processed meats and fried products, are positively associated with CVD risk [55, 56]. Intake of fish and nuts is inversely related to CVD risk [57,58,59]. Thus, it would be prudent to choose consume more fish and nuts, and avoid fried foods.

Participants in study all had the same demographic characteristics and would be likely to have shared similar genetic characteristics. Suboptimal diets that are positively associated with CVD have diverse characteristics in different occupations and regions [14], so it is important to examine dietary patterns in different populations with various sociocultural backgrounds. This study had two strengths. First, this study focused on CVD prevention, and identified the potentially high-risk group by calculating 10-year CVD risk score, which combined some major adverse cardiovascular events that will occur more frequently than single cardiovascular events [60]. Second, considering the complexity of diet, this study focused on dietary patterns instead of single foods or nutrients, providing evidence that suboptimal dietary patterns are associated with higher CVD risk score levels, conforming to current research trends in public health.

This study has certain limitations. A major limitation of its cross-section design is that causal inferences cannot be made. Thus, the long-term impact of dietary patterns on CVD need to be further confirmed [33]. In addition, over/underestimation due to recall bias may have been possible in this study, as the collection of data regarding food intake was dependent on the participants’ memories and motivation. Finally, there is the inherent subjectivity of both factor and cluster analysis derived patterns in the study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study showed that dietary patterns were associated with 10-year CVD risk score levels, which is consistent with previous studies conducted outside of China. Diet is a major modifiable factor in CVD prevention. This study provides evidence to food-based dietary guidelines that can be used to ameliorate people’s dietary habits. However, further study is also needed to confirm the long-term impact of these dietary patterns.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASCVD:

-

atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BP:

-

blood pressure

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- FFQ:

-

food frequency questionnaire

- ICVD:

-

ischemic cardiovascular disease

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

References

Joseph P, Leong D, McKee M, Anand SS, Schwalm JD, Teo K, et al. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: the epidemiology and risk factors. Circ Res. 2017;121:677–94. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.117.308903.

Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, Chen W, Wang L, Liu S, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387:251–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00551-6.

National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases. Report on cardiovascular diseases in China (2017). 2017. http://www.nccd.org.cn/News/Columns/Index/1089. Access Aug 13, 2018.

He J, Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Yao C, et al. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1124–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa050467.

Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, Ru X, Sun D, Wang L, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135:759–71. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250.

Hendryx M, Zullig KJ. Higher coronary heart disease and heart attack morbidity in Appalachian coal mining regions. Prev Med. 2009;49:355–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.011.

Hendryx M. Mortality from heart, respiratory, and kidney disease in coal mining areas of Appalachia. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82:243–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-008-0328-y.

Esch L, Hendryx M. Chronic cardiovascular disease mortality in mountaintop mining areas of central Appalachian states. J Rural Health. 2011;27:350–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00361.x.

Imamura F, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Fahimi S, Shi P, Powles J, et al. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e132–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(14)70381-x.

Rebello SA, Koh H, Chen C, Naidoo N, Odegaard AO, Koh WP, et al. Amount, type, and sources of carbohydrates in relation to ischemic heart disease mortality in a Chinese population: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:53–64. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.076273.

Anand SS, Hawkes C, de Souza RJ, Mente A, Dehghan M, Nugent R, et al. Food consumption and its impact on cardiovascular disease: importance of solutions focused on the globalized food system: a report from the workshop convened by the world heart federation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1590–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.050.

Li LM, Rao KQ, Kong LZ, Yao CH, Xiang HD, Zhai FY, et al. A description on the Chinese national nutrition and health survey in 2002. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2005;26:478–84.

Hong KN, Fuster V, Rosenson RS, Rosendorff C, Bhatt DL. How low to go with glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure in primary prevention of CVD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2171–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.001.

Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133:187–225. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585.

Dos Santos M, Penteado JO, Soares MCF, Muccillo-Baisch AL, Da Silva-Júnior FMR. Association between DNA damage, dietary patterns, nutritional status, and non-communicable diseases in coal miners. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:15600–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04922-8.

Schulte PA, Wagner GR, Ostry A, Blanciforti LA, Cutlip RG, Krajnak KM, et al. Work, obesity, and occupational safety and health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:428–36. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2006.086900.

Yuichi Yamada MI. Ikiko Tsuritani. Prevention of weight gain and obesity in occupational populations: a new target of health promotion services at worksites. J Occup Health. 2002;44:373–84. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.44.373.

Fan M, Lyu J, He P. Chinese guidelines for data processing and analysis concerning the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2014;35:961–4.

Xu SH, Qiao N, Huang JJ, Sun CM, Cui Y, Tian SS, et al. Gender differences in dietary patterns and their association with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Chinese: a cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2016;8:180. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8040180.

Writing Group of 2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension CHL, Chinese Society of Cardiology, Chinese Medical Doctor Association Hypertension Committee, Hypertension Branch of China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care, Hypertension Branch of Chinese Geriatric Medical Association. 2018 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiovasc Med. 2019;24:24–56. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2019.01.002.

Xiang YT, Ma X, Lu JY, Cai ZJ, Li SR, Xiang YQ, et al. Alcohol-related disorders in Beijing, China: prevalence, socio-demographic correlates, and unmet need for treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1111–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00933.x.

Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.20.2606.

Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physician, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine. Chinese expert consensus on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2010;49:174–85. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2010.02.031.

Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Chinese guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39:3–22.

Task Force on Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases(2017), Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Chinese guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases(2017). Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2018;46:10–25. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2018.01.004.

Fanelli KM, Bodt BA, Stave SE, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Dietary patterns associated with lower 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk among urban African-American and white adults consuming western diets. Nutrients. 2018;10:158. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020158.

Joint Committee Issued Chinese Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidemia in Adults. 2016 Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2016;44:833–53. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2016.10.005.

Wu Y, Liu X, Li X, Li Y, Zhao L, Chen Z, et al. Estimation of 10-year risk of fatal and nonfatal ischemic cardiovascular diseases in Chinese adults. Circulation. 2006;114:2217–25. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.607499.

He Y, Li Y, Lai J, Wang D, Zhang J, Fu P, et al. Dietary patterns as compared with physical activity in relation to metabolic syndrome among Chinese adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:920–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2012.09.001.

He Y, Ma G, Zhai F, Li Y, Hu Y, Feskens EJ, et al. Dietary patterns and glucose tolerance abnormalities in Chinese adults. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1972–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-0714.

Hu L. SAS statistical analysis tutorial. Beijing: Publishing House of Electronics Industry; 2010. p. 468–77.

Stricker MD, Onland-Moret NC, Boer JM, van der Schouw YT, Verschuren WM, May AM, et al. Dietary patterns derived from principal component- and k-means cluster analysis: long-term association with coronary heart disease and stroke. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:250–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2012.02.006.

Schulze MB, Hoffmann K. Methodological approaches to study dietary patterns in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:860–9. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20061731.

Newby PK, Tucker KL. Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:177–203.

Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1977;39:1–38.

Bhattacherjee A, Kunar BM, Baumann M, Chau N. The role of occupational activities and work environment in occupational injury and interplay of personal factors in various age groups among Indian and French coalminers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26:910–29. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13382-013-0165-4.

Deng M, Wu F, Wang J, Sun L. Musculoskeletal disorders, personality traits, psychological distress, and accident proneness of Chinese coal miners. Work. 2017;57:441–9. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-172569.

Hendryx M, Ahern MM. Relations between health indicators and residential proximity to coal mining in West Virginia. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:669–71. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2007.113472.

Alexander HM, Balding DJ, Dobson AJ, Gibberd RW, Lloyd DM, Leeder SR. Risk factors and heart disease mortality. A regional perspective. Med J Aust. 1986;144:20–2. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1986.tb113625.x.

Schulze MB, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fung TT, Lichtenstein AH, Forouhi NG. Food based dietary patterns and chronic disease prevention. BMJ. 2018;361:k2396. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2396.

Bilici S, Saglam F, Beyhan Y, Barut-Uyar B, Dikmen D, Goktas Z, et al. Energy expenditure and nutritional status of coal miners: a cross-sectional study. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2016;71:293–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2015.1095152.

Swartz S, Konishi F, Sanjabi P. Dietary assessment of coal miners in southern Illinois. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:1465–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/31.8.1465.

Brug J, Kremers SP, Lenthe F, Ball K, Crawford D. Environmental determinants of healthy eating: in need of theory and evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:307–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665108008616.

Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4567.

Li XY, Cai XL, Bian PD, Hu LR. High salt intake and stroke: meta-analysis of the epidemiologic evidence. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:691–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00355.x.

Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:791–813. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp139.

Abdulai T, Li Y, Zhang H, Tu R, Liu X, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of impaired fasting glucose, type 2 diabetes and associated risk factors in undiagnosed Chinese rural population: the Henan rural cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029628. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029628.

D'Elia L, Barba G, Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P. Potassium intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1210–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.070.

Huang L, Shang L, Yang W, Li D, Qi C, Xin J, et al. High starchy food intake may increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a nested case-control study in the Shaanxi province of northwestern China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2524-z.

Mohan V, Radhika G, Vijayalakshmi P, Sudha V. Can the diabetes/cardiovascular disease epidemic in India be explained, at least in part, by excess refined grain (rice) intake? Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:369–72. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814780903580307.

Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific report of the 2015 dietary guidelines advisory committee. 2015. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/. Accessed Mar 25 2015.

Mirrahimi A, de Souza RJ, Chiavaroli L, Sievenpiper JL, Beyene J, Hanley AJ, et al. Associations of glycemic index and load with coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e000752. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.112.000752.

Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281–3. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-1239.

Bhupathiraju SN, Tobias DK, Malik VS, Pan A, Hruby A, Manson JE, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 3 large US cohorts and an updated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:218–32. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.079533.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121:2271–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924977.

Micha R, Michas G, Lajous M, Mozaffarian D. Processing of meats and cardiovascular risk: time to focus on preservatives. BMC Med. 2013;11:136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-136.

Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes LT, Boffetta P, Greenwood DC, et al. Nut consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Med. 2016;14:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0730-3.

Eneroth H, Wallin S, Leander K, Nilsson Sommar J, Akesson A. Risks and benefits of increased nut consumption: cardiovascular health benefits outweigh the burden of carcinogenic effects attributed to aflatoxin b(1) exposure. Nutrients. 2017;9:E1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121355.

He K, Song Y, Daviglus ML, Liu K, Van Horn L, Dyer AR, et al. Fish consumption and incidence of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Stroke. 2004;35:1538–42. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000130856.31468.47.

Irony TZ. The “utility” in composite outcome measures: measuring what is important to patients. JAMA. 2017;318:1820–1. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.14001.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge the coalmine workers in our study for their time and participation. Authors would also like to acknowledge all interviewers for survey data collection work.

Funding

This research was funded from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (item number: 81872715). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TW and J-JH were responsible for the study concept and design. S-HX, J-SM, QS, HW cleared the data. HW, QG managed the data. QS, S-HX, J-KZ, HW performed statistical analysis. QS wrote the manuscript. TW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Shanxi Medical University Ethics Committee and obtained written consent from each individual.

Consent for publication

No applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Table S1

Demographic characteristics described based on four patterns. Table S2: Associations between patterns and 10-year ASCVD risk score level for miners in imputed dataset. Table S3: Associations between patterns and 10-year ICVD risk score level for miners in imputed dataset.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Q., Ma, JS., Wang, H. et al. Associations between dietary patterns and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk score levels among Chinese coal miners——a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 19, 1704 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8070-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8070-9