Abstract

Background

National smoking cessation strategies in Nigeria are hindered by lack of up-to-date epidemiologic data. We aimed to estimate prevalence of tobacco smoking in Nigeria to guide relevant interventions.

Methods

We conducted systematic search of publicly available evidence from 1990 through 2018. A random-effects meta-analysis and meta-regression epidemiologic model were employed to determine prevalence and number of smokers in Nigeria in 1995 and 2015.

Results

Across 64 studies (n = 54,755), the pooled crude prevalence of current smokers in Nigeria was 10.4% (9.0–11.7) and 17.7% (15.2–20.2) for ever smokers. This was higher among men compared to women in both groups. There was considerable variation across geopolitical zones, ranging from 5.4% (North-west) to 32.1% (North-east) for current smokers, and 10.5% (South-east) to 43.6% (North-east) for ever smokers. Urban and rural dwellers had relatively similar rates of current smokers (10.7 and 9.1%), and ever smokers (18.1 and 17.0%). Estimated median age at initiation of smoking was 16.8 years (IQR: 13.5–18.0). From 1995 to 2015, we estimated an increase in number of current smokers from 8 to 11 million (or a decline from 13 to 10.6% of the population). The pooled mean cigarettes consumption per person per day was 10.1 (6.1–14.2), accounting for 110 million cigarettes per day and over 40 billion cigarettes consumed in Nigeria in 2015.

Conclusions

While the prevalence of smokers may be declining in Nigeria, one out of ten Nigerians still smokes daily. There is need for comprehensive measures and strict anti-tobacco laws targeting tobacco production and marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is a leading cause of preventable deaths and morbidity, linked to high burden of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ischemic heart diseases and stroke [1,2,3]. It accounts for more than 7 million deaths annually with about 10% of these resulting from second-hand smoke [2]. There are around 1.1 billion smokers worldwide and about 80% of these live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where more than two-thirds of smoking-related deaths occur [2].

Though global current smoking rates among adults decreased from 23.5 to 20.7% between 2007 and 2015 [4], this reduction was largely due to the declining smoking rates in Northern and Western Europe, North America and the Western Pacific regions [3, 4], where considerable measures have been implemented to tackle tobacco smoking. Conversely, smoking rate appears to be increasing in the Middle East and Africa [4]. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, the consumption of tobacco increased by 57% between 1990 and 2009 [5]. A recent analysis of the Demographic Health Survey data of 30 sub-Saharan African countries revealed higher smoking rates, with prevalence as high as 37.7% among men in Sierra Leone [6].

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and has one of the leading tobacco markets in Africa, with over 18 billion cigarettes sold annually costing Nigerians over US$ 931 million [7, 8]. Following the 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) [2], Nigeria ratified the convention agreement in 2005, and in 2015 signed into law the National Tobacco Control (NTC) Act that regulates all aspects of tobacco control including advertising, packaging, and smoke-free areas [2]. Despite these initiatives, some reports suggest the prevalence of smoking in the country is rising at about 4% per year [8].

The WHO estimated about 13 million smokers in Nigeria in 2012 [7], with over 16,000 deaths attributable to smoking [9]. Increased commerce by international tobacco companies and the relative role they play in economic growth may have contributed to a rise in smoking rates [8, 10]. Although, some national estimates of smoking prevalence have been reported [11, 12], the exact number of smokers remains debated, which possibly hinders health policy. Concerns over current estimates include varying case definitions, representativeness of study samples or data, and poor study designs. We therefore conducted a comprehensive systematic search of the literature and synthesized data based on standard case definitions to estimate national and sub-national prevalence of smoking in Nigeria.

Methods

This is a review of publicly available studies and conducted as part of series on the epidemiology of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Nigeria. Methods have been described in detail in previous studies [13,14,15,16]. No ethical approval was required. Study was conducted in line with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [17].

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health and Africa Journals Online (AJOL) on 31 January 2019. We initially searched for epidemiological studies on smoking in Nigeria and sourced for unpublished reports (or studies) from Google searches and Google Scholar. We included studies that were (i) population-based, (ii) reporting on the prevalence of smoking (current or ever) in a Nigerian setting, and (iii) published on or after 01 January 1990. Search terms are presented in the Additional file 1.

Case definitions

We selected studies that defined smoking as “smoking of tobacco products, be it cigarettes, bidi, cigar, hookah, pipe, or other related manufactured products and hand rolled stuffs”. We defined current smoker as someone who smokes every day, or some days in the last 30 days preceding an interview. An ex-smoker (or former smoker) is someone who was an every-day smoker or has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime but has currently quit smoking [2, 18, 19]. An ever smoker is defined as anyone who has quit smoking (smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime) or currently smokes. This describes life-time smoking status and satisfies the definition of either a current or former smoker [19, 20].

Data extraction

DA and AA independently reviewed and assessed studies using a pre-defined guideline to ensure consistency in studies’ selection (disagreements were resolved by consensus). From each study, we extracted number of smokers, sample size, mean (or median) age, and estimated prevalence of smoking (and confidence intervals (CI). These were matched to the study period, site, geopolitical zone and setting, respectively. Quality of studies was assessed during data extraction, adapting a previously used guideline [21,22,23,24]. This was based on representativeness of the sample, appropriate design and analysis, and standard case definitions, with each study graded as high, moderate, or low (Additional file 1).

Data analysis

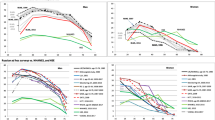

We employed a random-effects meta-analysis, using the DerSimonian and Laird Method [25], to combine individual study estimates and generate national and sub-national pooled estimates of the prevalence of tobacco smoking in Nigeria. Assuming a binomial (or Poisson) distribution, we estimated standard errors from crude prevalence and sample. Heterogeneity was identified from subgroup analyses, and assessed using I-squared (I2) statistics. To show trends and changes in smoking prevalence in the country, a meta-regression model accounting for the study period, and age was developed. Age-adjusted prevalence estimates were generated from the model for years 1995 and 2015. These were employed to estimate the absolute number of current and ever smokers in Nigeria based on the United Nations population (five-year age groups) for Nigeria for the two years [26]. This model has been described in detail in previous studies [13,14,15,16]. All statistical analyses were conducted on Stata (Stata Corp V.14, Texas, USA).

Results

Search results

A total of 1474 records were retrieved from the databases – 546 studies in MEDLINE, 654 in EMBASE, 229 in Global Health, and 45 in AJOL. Twenty-two studies were identified from additional searches. We screened 967 titles were for relevance (i.e. epidemiologic studies on smoking in Nigeria) after removing duplicates, with 794 articles excluded. Abstracts and full-texts of the remaining 173 articles were accessed and screened. We retained 64 studies for synthesis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The 64 studies covered the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria (Table 1). The South-west returned 40.6% (26 studies) of all selected articles, followed by South-south (19%, 12 studies), and South-east and North-central (13%, 8 studies). The North-west was covered in four studies (6.3%), while the North-east had the lowest coverage with two studies (3.1%). Most studies (77.1%, 43 studies) were conducted in urban settings, while rural settings had 10 studies (15.6%), and 11 studies (17.2%) were from mixed urban and rural settings. Using our quality criteria, 25 studies (39%) were rated as high quality, and 39 (61%) rated as moderate. All studies were conducted under one year, with study year ranging from 1990 to 2017. The total population covered from all selected studies was 54,755, with the mean (or median) age of samples ranging from 15 to 55.5 years (Table 1 and Additional file 1). Heterogeneity was high across studies, with I-squared (I2) estimated at 98.2% (P < 0.001). This was generally high (I2> 95%) across subgroups (ie. sex, geopolitical zones, geographical settings) (Table 2).

Prevalence of tobacco smoking in Nigeria

Current smokers

The prevalence of current smokers ranged from 1.2% recorded in Yaba Lagos, South-west Nigeria in 2015 [44], to 55.5% in Amassoma Delta State, South-south Nigeria, also in 2015 [69]. The pooled crude prevalence of current smokers in Nigeria was 10.4% (95% CI: 9.0–11.7), with this significantly lower among women (3.6%, 2.8–4.4), compared to men (13.4%, 10.0–16.8) (Table 2). Following a sensitivity analysis, the prevalence of current smokers in the general population at 8.8% (7.5–10.2) was comparable to the overall pooled estimate (10.4%), while a higher estimate was reported among specific populations (eg. commercial drivers, soldiers, and healthcare students) at 17.3% (11.5–23.1) (Fig. 2). Across the geopolitical zones, the prevalence rate of current smokers was significantly higher in the North-east (32.1%, 30.0–34.1), compared to the other five geopolitical zones. The South-south region had a prevalence of 13.0% (8.7–17.3), North-central 10.3% (6.0–14.4), South-west 8.9% (6.9–11.0), South-east 8.6% (4.1–13.0) and North-west 5.4% (3.7–7.2) (Table 2). There was relatively no difference in the prevalence of current smokers across geographical settings, with the urban and rural settings having a prevalence of 10.7% (8.8–12.6) and 9.1% (5.1–13.0), respectively (Table 2 and Additional file 1).

Ever smokers

The lowest prevalence of ever smokers was recorded in Ibadan Oyo State, South-west Nigeria in 2009 at 2.1% [77], while the highest was reported in Amassoma Delta State, South-south Nigeria in 2015 at 64.6% [69]. The pooled crude prevalence of ever smokers (i.e. life-time prevalence of smoking) was 17.7% (95% CI: 15.2–20.2) (Table 2). As observed among current smokers, the prevalence was significantly higher among men at 22.8% (17.5–28.2), compared to women at 6.3% (4.8–7.7) (Table 2). When population characteristics were considered in the sensitivity analysis, the prevalence of ever smokers in the general population was 15.3% (12.9–17.6), which was comparable to the overall estimate (17.7%), in contrast to a relatively higher estimate among specific population groups at 30.7% (17.7–43.7) (Fig. 3). The pooled prevalence of ever smokers was highest in the North-east at 43.6% (31.5–55.7), with lowest recorded in the South-east at 10.5% (3.7–17.4) and the North-west at 12.4% (7.9–16.9). The South-south and South-west have a relatively similar pooled prevalence rates of ever smokers at 16.9% (11.4–22.3) and 17.1% (12.8–21.4), respectively. The pooled prevalence was minimally higher in urban settings at 18.1% (14.6–21.6) compared to rural settings at 16.8% (10.8–22.8) (Table 2).

Age at initiation of smoking

Most studies reported the mean or median age at initiation of smoking during adolescence, with this ranging from 12 years in Ibadan Oyo State, South-west Nigeria [55], to 21.9 years in Lagos Mainland, South-west Nigeria [72]. From all studies, the estimated median age at initiation of smoking was 16.75 years (interquartile range: 13.5–18.0).

Estimated number of current and ever smokers in Nigeria

Based on the model, the age-adjusted prevalence of current smokers decreased with advancing age, while the prevalence increased with advancing age for ever smokers (Table 3). Using the United Nations demographic projections for Nigeria, we estimated about 8 million current smokers in Nigeria in 1995 among person aged 15 years or more, with this increasing to about 11 million current smokers by 2015. The age-adjusted prevalence of current smokers actually decreased from 13.0 to 10.6% over this period (Table 3). On the contrary, both the prevalence and number of ever smokers increased over the same period, from about 10.9 million (17.6%) in 1995 to 19.8 million (19.2%) in 2015 (Table 3).

Cigarettes consumed per day

Among current smokers, the mean cigarettes consumed per person per day ranged from 2 (1.0–3.4) recorded in a semi-urban setting in Abraka Delta State, South-south Nigeria [31], to 23.7 (21.3–26.1) in a rural area in Oyo State, Nigeria [81]. The pooled mean cigarettes consumption per person per day from all studies was 10.1 (6.1–14.2) (Table 3, Fig. 4). When considered in terms of the absolute number of current smokers in Nigeria in 2015 (11 million), this accounts for about 110 million cigarettes per day and over 40 billion cigarettes in Nigeria in 2015.

Discussion

This study integrated smoking information from 64 moderate to high-quality studies to estimate the current prevalence of smoking in Nigeria. Although the prevalence of ever smokers increased between 1995 and 2015, we observed a decreasing prevalence of current smokers over the same period. This trend is in contrast to estimates reported, albeit based on limited data, in some countries insub-Saharan Africa, who have experienced rising smoking rates due to changing socio-economic status, rural-urban migration and increased cigarette affordability [91]. The decreasing smoking rates in Nigeria possibly reflect increased health risk awareness and better overall measures to help smokers quit in the country. For example, in a national survey, Kale and colleagues [92] reported that in the 12 months preceding their study, almost half of current smokers attempted to quit smoking, with over two-thirds of these receiving advice from care providers and counselors.

Despite the declining rates, we estimated about 11 million current smokers (10.6%) and 20 million ever smokers (19.2%) in 2015, which are still unacceptably high from an absolute perspective. In a nation-wide survey in 2012 [11], the prevalence of current smokers was 4% among adults Nigerians. This is much lower than estimated in this study, presumably due to challenges with sampling and case ascertainment. In a recent scoping exercise, Adeoye et al. [93] estimated a prevalence of current smokers at 19.7%. However, this estimate was not age-standardized, and a lower prevalence of ever smokers reported raises concerns on the quality of data. However, in 2015, the WHO reported a current smoking prevalence of about 9% among persons aged 15 years or more (17% among men and 1% among women) in Nigeria [7]. The overall prevalence and sex distribution are almost as reported in the current study. The higher smoking prevalence among men in Nigeria is well-documented [10, 93]. This perhaps represents a sustained pattern of smoking epidemic, and presents a valuable opportunity for developing effective policies and interventions learning from actions in developing countries [94, 95].

The median age at initiation of smoking in this study (16.8 years) is relatively low, reflective of a growing burden among adolescents and youths. Kale and colleagues [92] in their nation-wide survey noted that about two-thirds of the population started smoking before attaining 20 years. Adeoye et al. [93] reported lower age at initiation of 14.7 years in the country. Many have advocated for stiffer anti-tobacco laws in the country, particularly to address a growing use of tobacco products among youths [11].

The prevalence of smokers was notably higher in North-east Nigeria which may be expected given an ongoing armed conflict lasting more than a decade. Although the evidence of the association between smoking and conflict is limited and inconclusive [96], varying social situations among vulnerable populations are known to precipitate substance use [97]. With several persons displaced, children and adolescents out of school, and youths without jobs, substance use, including tobacco products, is likely to increase in these settings. Although Kale and colleagues [92] reported South-easterners as the highest consumers of tobacco products in the country, the deviance from our estimates suggests a need for more research to understand regional variations.

Although the NTC Act was signed into law in 2015 and the country has committed to the WHO FCTC since 2005 [18], Nigeria is not yet on track to achieve tobacco control targets [98]. For example, our estimates show that rural dwellers smoke almost at the same rate as urban dwellers, indicating that smoking, believed to be associated with urbanization, has gradually penetrated remote areas. Further, we estimated that current smokers consume an average of 10 cigarettes per person per day accounting for about 110 million cigarettes per day and over 40 billion cigarettes in 2015 alone. Vellios et al. [99] noted that the demand for cigarettes increased by 44% across many African countries between 1990 and 2012, with this leading to over 100% increase in cigarettes production over the same period in these countries. A thriving tobacco market raises serious public health concerns, particularly for a country with a relatively weak health system. Tobacco companies see these countries as emerging markets due to weak tobacco control regulations and several vulnerable populations [91, 94]. Careful incorporation of the WHO MPOWER package (targeted at reversing tobacco epidemic) [18] beyond the national level to state and local levels may complement successful measures like smoke-free legislation, taxes, health education and media campaigns [2, 7]. Besides, Nigeria needs to develop comprehensive surveillance systems to monitor the production, sales, and consumption of cigarettes to effectively achieve control targets [99].

The strength of this review lies in the number of studies retained (64) and population covered (54755), which spread across all geopolitical zones in the country. Herein, we have perhaps addressed an issue bordering on representativeness, which appears to be a leading concern in the understanding of the epidemiology of smoking in Nigeria [10]. We acknowledge that pooling prevalence rates from a range of studies conducted over a 27-year period (1990–2017) could affect reliability of our overall estimates; however, this was mainly done to understand the trend in smoking rates over this period, which our model and age-adjusted estimates clearly reflect (Table 3). Nonetheless, our estimates should be considered with the high heterogeneity reported. This perhaps could be due to diverse population characteristics, particularly those contributed by specific population groups. Our sensitivity analysis may have addressed this (ie. comparing general to specific populations), as excluding some of specific populations with higher prevalence of smoking could imply missing some necessary information on the use of tobacco and related products in the country. Varying study designs are also important sources of heterogeneity. Due to data limitations, we could not investigate other sources of heterogeneity, including socio-economic status, wealth index, employment status and religion. Finally, there were only two studies from the North-east, this should guide interpretation of the high estimates in the region.

Conclusion

While the prevalence of current smokers may be declining in Nigeria, the absolute number of active smokers remain one of the highest in Africa. Economic growth, improved socio-economic status, rapid migration, and increased cigarette affordability are key factors. As rural dwellers are almost as affected as urban dwellers, careful consideration is required during programming. Comprehensive measures and strict anti-tobacco laws targeting tobacco production and marketing need to be enforced across country levels.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- AJOL:

-

Africa Journals Online

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- NCDs:

-

Non-Communicable Diseases

- NTC:

-

National Tobacco Control

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Hecht SS. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):733.

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326043/9789241516204-eng.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2019.

Drope J, Schluger N, Cahn Z, Drope J, Hamill S, Islami F, et al The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta: American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies. 2018.

Scollo M, Winstanley M. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. 2018.

Eriksen M, Nyman A, Whitney C. Global tobacco use and cancer: findings and solutions from the tobacco atlas. 2014. Available from: http://cancercontrol.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/43-48-Eriksen_cc2014.pdf. 28 December 2018

Sreeramareddy CT, Pradhan PM, Sin S. Prevalence, distribution, and social determinants of tobacco use in 30 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):243.

World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in tobacco smoking 2000–2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/. Accessed 21 Jan 2019.

Ake A. Nigeria: Tobacco Consumption Contributes 12% Deaths From Heart Diseases - NHF. THISDAY. 2018 17 May 2018.

The Tobacco Atlas. Nigeria. Available from: https://tobaccoatlas.org/country/nigeria/. Accessed 28 Dec 2018.

Oyewole BK, Animasahun VJ, Chapman HJ. Tobacco use in Nigerian youth: A systematic review. PloS One. 2018;13(5):e0196362.

Adeniji F, Bamgboye E, van Walbeek C. Smoking in Nigeria: Estimates from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2012. Stroke. 2016;2:3.

Mbulo L, Kruger J, Hsia J, Yin S, Salandy S, Orlan EN, et al. Cigarettes point of purchase patterns in 19 low-income and middle-income countries: Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2008–2012. Tobacco Control:2018.

Adeloye D, Basquill C, Aderemi AV, Thompson JY, Obi FA. An estimate of the prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2015;33(2):230–42.

Adeloye D, Ige JO, Aderemi AV, Adeleye N, Amoo EO, Auta A, et al. Estimating the prevalence, hospitalisation and mortality from type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015424.

Adeloye D, Olawole-Isaac A, Auta A, Dewan MT, Omoyele C, Ezeigwe N, et al. Epidemiology of harmful use of alcohol in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(5):438–50.

Adeloye D, Abaa DQ, Owolabi EO, Ale BM, Mpazanje RG, Dewan MT, et al. Prevalence of hypercholesterolemia in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2019;178:167–78.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

World Health Organization. MPOWER: a policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult Tobacco Use Information: National Health Interview Survey: CDC; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/tobacco/tobacco_glossary.htm. [02 October 2019]

Parekh TM, Wu C, McClure LA, Howard VJ, Cushman M, Malek AM, et al. Determinants of cigarette smoking status in a national cohort of black and white adult ever smokers in the USA: a cross-sectional analysis of the REGARDS study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e027175.

Stanifer JW, Jing B, Tolan S, Helmke N, Mukerjee R, Naicker S, et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(3):e174–e81.

Pai M, McCulloch M, Gorman JD, Pai N, Enanoria W, Kennedy G, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: an illustrated, step-by-step guide. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:86–95.

Guyatt GH, Rennie D. Users' guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice Chicago: AMA Press; 2002.

Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–6.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

United Nations. 2017 Revision of World Population Prospects. New York, US: United Nations; 2017. Available from: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/. Accessed 28 Dec 2018.

Obaseki D, Erhabor G, Burney P, Buist S, Awopeju O, Gnatiuc L. The prevalence of COPD in an African city: Results of the BOLD study, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Eur Respiratory Soc. 2013.

Desalu OO. Prevalence of chronic bronchitis and tobacco smoking in some rural communities in Ekiti state, Nigeria. The Niger Postgrad Med J. 2011;18(2):91–7.

Harris-Eze AO. Smoking habits and chronic bronchitis in Nigerian soldiers. East Afr Med J. 1993;70(12):763–7.

Ozoh O, Balogun B, Oguntunde O, Nwizu C, Roberts A, Inem V, et al. The prevalence and determinants of COPD in an urban community in Lagos, Nigeria. Eur Respiratory Soc. 2013.

Arute J, Oyita G, Eniojukan J. Substance Abuse among Adolescents: 2. Prevalence and Patterns of Cigarette smoking among senior secondary school students in Abraka, Delta State, Nigeria. IOSR J Pharm. 2015;5(1):40–7.

Abiola A, Balogun O, Odukoya O, Olatona F, Odugbemi T, Moronkola R, et al. Age of initiation, Determinants and Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking among Teenagers in Mushin Local Government Area of Lagos State, Nigeria. APJCP. 2016;17(3):1209–14.

Adebiyi AO, Faseru B, Sangowawa AO, Owoaje ET. Tobacco use amongst out of school adolescents in a Local Government Area in Nigeria. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5:24.

Adepoju EG, Olowookere SA, Adeleke NA, Afolabi OT, Olajide FO, Aluko OO. A population based study on the prevalence of cigarette smoking and smokers' characteristics at osogbo,Nigeria. Tobacco Use Insights. 2013;6:1–5.

Agaba EI, Akanbi MO, Agaba PA, Ocheke AN, Gimba ZM, Daniyam S, et al. A survey of non-communicable diseases and their risk factors among university employees: a single institutional study. Cardiovascular J Afr. 2017;28(6):377–84.

Agaku IT, Filippidis FT. Prevalence, determinants and impact of unawareness about the health consequences of tobacco use among 17,929 school personnel in 29 African countries. BMJ open. 2014;4(8):e005837.

Aina BA, Oyerinde OO, Joda AE, Dada OO. Cigarette smoking among healthcare professional students of University of Lagos and Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Idi-Araba, Lagos, Nigeria. Niger Q J Hospital Med. 2009;19(1):42–6.

Azodo CC, Omili M. Tobacco use, Alcohol Consumption and Self-rated Oral Health among Nigerian Prison Officials. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(11):1364–71.

Awopeju O, Erhabor G, Awosusi B, Awopeju O, Adewole O, Irabor I. Smoking prevalence and attitudes regarding its control among health professional students in South-Western Nigeria. Annals Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(3):355–60.

Anyanwu OU, Ibekwe RC, Ojinnaka NC. Pattern of substance abuse among adolescent secondary school students in Abakaliki. Cogent Med. 2016;3(1):1272160.

Akinbodewa AA, Adejumo AO, Koledoye OV, Kolawole JO, Akinfaderin D, Lamidi AO, et al. Community screening for pre-hypertension, traditional risk factors and markers of chronic kidney disease in Ondo State, South-Western Nigeria. The Niger Postgrad Med J. 2017;24(1):25–30.

Babatunde LS, Babatunde OT, Oladeji SM, Ashipa T. Prevalence and determinants of susceptibility to cigarette smoking among non-smoking senior secondary school students in Ilorin, North Central Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017.

Babatunde OA, Elegbede OE, Ayodele LM, Atoyebi OA, Ibirongbe DO, Adeagbo AO. Cigarette Smoking Practices and Its Determinants Among University Students in Southwest, Nigeria. J Asian Sci Res. 2012;2(2):62–9.

Dania MG, Ozoh OB, Bandele EO. Smoking habits, awareness of risks, and attitude towards tobacco control policies among medical students in Lagos Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2015;14(1):1–7.

Desalu O, Olokoba A, Danburam A, Salawu F, Issa B. Epidemiology of tobacco smoking among adults population in north-east Nigeria. The Internet J Epidemiol. 2008;6(1).

Desalu OO, Salami AK, Fawibe AE. Prevalence of cough among adults in an urban community in Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(5):337–41.

Ebirim CIC, Amadi AN, Abanobi OC, Iloh GUP. The prevalence of cigarette smoking and knowledge of its health implications among adolescents in Owerri, South-Eastern Nigeria. Health. 2014;6(12):1532–8.

Ekanem US, Opara DC, Akwaowo CD. High blood pressure in a semi-urban community in south-south Nigeria: a community-based study. African health sciences. 2013;13(1):56–61.

Emerole CO, Aguwa EN, Onwasigwe CN, Nwakoby BA. Cardiac risk indices of staff of Federal University Of Technology Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2007;9(2):132–5.

Fatoye FO, Morakinyo O. Substance use amongst secondary school students in rural and urban communities in south western Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2002;79(6):299–305.

Fawibe A, Shittu A. Prevalence and characteristics of cigarette smokers among undergraduates of the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14(2):201–5.

Hussain NA, Akande TM, Adebayo O. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and the knowledge of its health implications among Nigerian soldiers. East Afr J Public Health. 2009;6(2):168–70.

Ibekwe R. Modifiable Risk factors of Hypertension and Socio-demographic Profile in Oghara, Delta State; Prevalence and Correlates. Annals Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5(1):71–7.

Makanjuola AB, Daramola TO, Obembe AO. Psychoactive substance use among medical students in a Nigerian university. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):112–4.

Morakinyo J, Odejide AO. A community based study of patterns of psychoactive substance use among street children in a local government area of Nigeria. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(2):109–16.

Obot IS. The use of tobacco products among Nigerian adults: a general population survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1990;26(2):203–8.

Odey FA, Okokon IB, Ogbeche JO, Jombo G, Ekanem E. Prevalence of cigarette smoking among adolescents in Calabar city, south-eastern Nigeria. J Med Med Sci. 2012;3(4):237–42.

Odeyemi KA, Osibogun A, Akinsete AO, Sadiq L. The Prevalence and Predictors of Cigarette Smoking among Secondary School Students in Nigeria. The Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16(1):40–5.

Odugbemi TO, Onajole AT, Osibogun AO. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors amongst traders in an urban market in Lagos, Nigeria. The Niger Postgrad Med J. 2012;19(1):1–6.

Lawoyin TO, Asuzu MC, Kaufman J, Rotimi C, Owoaje E, Johnson L, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in an African, urban inner city community. West Afr J Med. 2002;21(3):208–11.

Ige OK, Owoaje ET, Adebiyi OA. Non communicable disease and risky behaviour in an urban university community Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(1):62–7.

Ugwuja E, Ogbonna N, Nwibo A, Onimawo I. Overweight and Obesity, Lipid Profile and Atherogenic Indices among Civil Servants in Abakaliki, South Eastern Nigeria. Annals Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(1):13–8.

Odukoya OO, Odeyemi KA, Oyeyemi AS, Upadhyay RP. Determinants of smoking initiation and susceptibility to future smoking among school-going adolescents in Lagos State, Nigeria. APJCP. 2013;14(3):1747–53.

Okagua J, Opara P, Alex-Hart BA. Prevalence and determinants of cigarette smoking among adolescents in secondary schools in Port Harcourt, Southern Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;28(1):19–24.

Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sodiq O, Shoyinka K, Adedapo K, Falase AO. A prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural Yoruba south-western Nigerian population: a population-based survey. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21(1):26–31.

Onofa L Prevalence and pattern of drug abuse among students of three tertiary institutions in Abeokuta: A Dissertation submitted to the West African College of Physicians, Faculty of Psychiatry; 2006.

Onyeonoro UU, Chukwuonye II, Madukwe OO, Ukegbu AU, Akhimien MO, Ogah OS. Awareness and perception of harmful effects of smoking in Abia State, Nigeria. Niger J Cardiol. 2015;12(1):27.

Oshodi OY, Aina OF, Onajole AT. Substance use among secondary school students in an urban setting in Nigeria: prevalence and associated factors. Afr J Psychiatry. 2010;13(1):52–7.

Owonaro P, Eniojukan J. Cigarette Smoking Practices, Perceptions and Awareness of Government Policies among Pharmacy Students in Niger Delta University in South-South Nigeria. UK J Pharm Biosci. 2015;3(5):20–9.

Owonaro P, Eniojukan J. The Prevalence and Contextual Correlates of Smoking in Opokuma Clan of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Int J Adv Pharm Biol Chem. 2015;4(3):656–67.

Ozoh OB, Dania MG, Irusen EM. The Prevalence of Self-Reported Smoking and Validation with Urinary Cotinine Among Commercial Drivers in Major Parks in Lagos, Nigeria. J Public Health Afr. 2014;5(1):316.

Ozoh OB, Akanbi MO, Amadi CE, Vollmer W, Bruce N. The prevalence of and factors associated with tobacco smoking behavior among long-distance drivers in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(3):886–95.

Raji M, Abubakar I, Oche M, Kaoje A. Prevalence and determinants of cigarette smoking among in school adolescents in Sokoto metropolis, Northwest Nigeria. Int J Trop Med. 2013;8(3):81–6.

Raji M, Usman A, Umar M, Oladigbolu R, Kaoje A. Cigarette Smoking among Out-of-School Adolescents in Sokoto Metropolis, North-West Nigeria. Health Sci J. 2017;11(3).

Salawu F, Danburam A, Isa B, Agbo J. Cigarette smoking habits among adolescents in northeast Nigeria. Internet J Epidemiol. 2010;8(1):1.

Shehu AU, Idris SH. Marijuana smoking among secondary school students in Zaria, Nigeria: factors responsible and effects on academic performance. Annals Afr Med. 2008;7(4):175–9.

Yisa IO, Lawoyin TO, Fatiregun AA, Emelumadu OF. Pattern of substance use among senior students of command secondary schools in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2009;18(3):286–90.

Abasiubong F, Atting I, Bassey E, Ekott J. A comparative study of use of psychoactive substances amongst secondary school students in two local Government Areas of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11(1):45–51.

Uwakwe R, Gureje O. Sociodemographic correlates of continuing tobacco use - a descriptive report from the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(6):506–13.

Gureje O, Degenhardt L, Olley B, Uwakwe R, Udofia O, Wakil A, et al. A descriptive epidemiology of substance use and substance use disorders in Nigeria during the early 21st century. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(1):1–9.

Lasebikan VO, Ola BA. Prevalence and Correlates of Alcohol Use among a Sample of Nigerian Semirural Community Dwellers in Nigeria. 2016;2016:2831594.

Odenigbo CU, Oguejiofor OC, Odenigbo UM, Ibeh CC, Ajaero CN, Odike MA. Prevalence of dyslipidaemia in apparently healthy professionals in Asaba, South South Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11(4):330–5.

Forrest KY, Bunker CH, Kriska AM, Ukoli FA, Huston SL, Markovic N. Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors in a developing population. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(9):1598–604.

Oguoma VM, Nwose EU, Skinner TC, Digban KA, Onyia IC, Richards RS. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among a Nigerian adult population: relationship with income level and accessibility to CVD risks screening. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:397.

Ezejimofor MC, Uthman OA, Maduka O, Ezeabasili AC, Onwuchekwa AC, Ezejimofor BC, et al. The Burden of Hypertension in an Oil- and Gas-Polluted Environment: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. American J Hypertens. 2016;29(8):925–33.

Ezekwesili CN, Ononamadu CJ, Onyeukwu OF, Mefoh NC. Epidemiological survey of hypertension in Anambra state, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19(5):659–67.

Ogah OS, Madukwe OO, Chukwuonye II, Onyeonoro UU, Ukegbu AU, Akhimien MO, et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in Abia State Nigeria: results from the Abia State Non-Communicable Diseases and Cardiovascular Risk Factors Survey. Ethn Dis. 2013;23(2):161–7.

Suleiman IA, AE O, Ganiyu KA. Prevalence and control of hypertension in a Niger Delta semi urban community, Nigeria. Pharm Pract. 2013;11(1):24–9.

Ugwuja E, Ezenkwa U, Nwibo A, Ogbanshi M, Idoko O, Nnabu R. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in an agrarian rural community in southeast Nigeria. Annals Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5(1):45–9.

Wahab KW, Okokhere PO, Ugheoke AJ, Oziegbe O, Asalu AF, Salami TA. Awareness of warning signs among suburban Nigerians at high risk for stroke is poor: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:18.

Drope J, Schluger N, Cahn Z, Drope J, Hamill S, Islami F, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta. 2018.

Kale Y, Olarewaju I, Usoro A, Ilori E, Ogbonna N, Ramanandraibe N, et al. Global adult tobacco survey: country report 2012. Abuja. 2012.

Adeoye O, Sowunmi A, Adewuyi G, Lofinmakin B, Osadolor U, Amoo EO, et al Estimating the prevalence and health risks awareness of smoking in Nigeria: A meta-analysis approach. Afr Popul Stud. 2018;32(1).

Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T, d'Espaignet ET, Stevens GA, Commar A, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. Lancet (London, England). 2015;385(9972):966–76.

Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tobacco Control. 1994;3(3):242–7.

Lo J, Patel P, Roberts B. A systematic review on tobacco use among civilian populations affected by armed conflict. Tobacco Control. 2016;25(2):129–40.

Jawad M, Khader A, Millett C. Differences in tobacco smoking prevalence and frequency between adolescent Palestine refugee and non-refugee populations in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the West Bank: cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Conflict Health. 2016;10:20.

Hussain NA, Akande M, Adebayo ET. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and knowledge implications among Nigerian soldiers of its health. East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7(1):81–3.

Vellios N, Ross H, Perucic A-M. Trends in cigarette demand and supply in Africa. PloS One. 2018;13(8):e0202467.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health and the WHO Nigeria Country Office in the conduct of this study. Special thanks to the Centre for Global Health, and the NIHR Global Health Respiratory Unit (RESPIRE), Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, UK.

Funding

MOH is supported by a grant (K99HL141678) from the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). NHLBI had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DA conceived and designed the study. DA and AA conducted the literature searches and data extraction. DA and AA wrote the first draft. DA and MOH conducted the analysis. DA, AA, MTD, CO, AF, MG, NE, RGM, WA, MOH, and IFA contributed to the final draft and checked for important intellectual content. All authors approved the manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a review of publicly available studies. No ethical approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Search terms on tobacco smoking in Nigeria. Table S2. Quality assessment of selected studies. Table S3. Quality appraisal guide. Table S4. All extracted data employed in analysis. Figure S1. Crude prevalence rate of current smokers in Nigeria, by geopolitical zones. Figure S2. Crude prevalence rate of ever smokers in Nigeria, by geopolitical zones. Figure S3. Pooled mean cigarettes consumed per person per day in Nigeria. Figure S4. Meta-regression modelling.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Adeloye, D., Auta, A., Fawibe, A. et al. Current prevalence pattern of tobacco smoking in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 19, 1719 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8010-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8010-8