Abstract

Background

Despite emerging research about the role of the family and home environment on early childhood obesity, little is known on how weight-related behaviors, parent practices and the home environment influence overweight/obesity in older children and adolescents.

Methods

This analysis used data from a cross-sectional, representative population survey of Australian children age 5–16 years conducted in 2015. Data included measured anthropometry to calculate body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR; waist circumference/height). Information on home-based weight-related behaviors (individual eating and screen time behaviors, parent influences including rules and home environment factors) were measured using established short questions, with parental proxy reporting for children in up to grade 4, and self-report for students in grades 6, 8 and 10. Logistic regression models were used to examine associations between weight status and home-based weight-related behaviors.

Results

Both children and adolescents who did not consume breakfast daily were more likely to be overweight/obese OR (95% CI) = 1.39 (1.07–1.81) p = 0.015, OR (95% CI) =1.42 (1.16–1.74) p = 0.001, respectively, adjusted for age, gender, socio-economic status, rural/urban residence and physical activity. There was also a significant positive association with higher waist-to-height ratio in both children and adolescents. Among children, having a TV in the bedroom was also associated with overweight and obesity OR (95% CI) = 1.54 (1.13–2.09) p = 0.006 and higher waist-to-height ratio. For adolescents, parenting practices such as having no rules on screen-time, OR (95% CI) = 1.29 (1.07–1.55) p = 0.008, and rewarding good behavior with sweets, OR (95% CI) = 2.18 (1.05–4.52) p = 0.036, were significant factors associated with overweight and obesity. The prevalence of these obesogenic behaviors were higher in certain sub-groups of children and adolescents, specifically those from social disadvantage and non-English-speaking backgrounds.

Conclusions

Interventions to reduce the prevalence of obesity and overweight should include promoting daily breakfast, reducing screen-time, and encouraging health-promoting parenting practices. Interventions should particularly focus on those at some social disadvantage and from non-English-speaking backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Concern about the high global prevalence of childhood obesity has resulted in considerable research efforts to understand factors associated with unhealthy weight gain [1]. Many behaviors which have been associated with a higher prevalence of obesity, such as poor diet quality, low physical activity and excessive screen-time, track from childhood and adolescence into adulthood [2]. A theoretical framework for understanding the influences of personal and environmental factors that influence behavior is the socio-ecological model (SEM) and this has been used extensively in child obesity research [3].

The SEM comprises five levels of influence, individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and society and effective prevention and reduction programs should address each of these levels [4]. At an individual and interpersonal level, parents and the home environment are central to the development of a child’s attitudes, beliefs, knowledge and behavior [5]. Understanding eating and activity practices within the home and family environment, which lay the foundation for healthy lifestyles later in life, are fundamental to inform obesity prevention interventions [6].

A child’s home environment is a central influence on their food and eating habits as well as their physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns, particularly screen-time [7] and certain behaviors and environments in the home appear to be more obesogenic than others [8]. For example, eating behaviors known to increase weight status in children and adolescents include skipping breakfast [9], eating dinner in front of the television [10] and eating fast food regularly [11]. Parenting practices such as rewarding children with sweets for good behavior [12] and allowing children unrestricted access to sweet snacks and beverages [13] are known to be associated with increases in obesity. Other parenting practices, such as modeling of good health behaviors, and rule setting with regard to snacking and soft drinks may potentially be protective against overweight and obesity in children [5, 14].

Screen-time (i.e., television, computers, e-devices such as smart phones, tablets) is the most popular sedentary behavior of children and adolescents and high amounts of screen time have been associated with overweight, obesity and poor dietary habits [15]. Parent’s screen-time is known to influence children’s screen-time [16] and there is evidence that homes where there are rules on children’s use of screen devices for recreational purposes provide some protection against overweight and obesity [17].

To date, most interventions to prevent obesity in the home environment have involved children age 0–5 years and are focused on early feeding and parenting [18,19,20] . While successful child obesity prevention intervention efforts must involve parents during the early stages of child development, the current childhood obesity prevalence suggests the need to provide parents of school age children and adolescents with support to implement healthy practices within the home environment. Identifying parent practices and factors in the home environment that strongly influence childhood overweight/obesity, and the socio-demographic characteristics of children and adolescents at greater risk of engaging in unhealthy weight-related behaviors, can lead to better targeted interventions.

The purpose of this study was to use population health survey data from children age 5–16 years to explore the associations between less healthy individual behaviors, parent influences, the home environment and child and adolescent overweight and obesity. We also examined the associations by socio-demographic characteristics to identify which sub-groups of children are at greater risk of less healthy practices and would benefit most from interventions.

Methods

This is a secondary data analysis of the 2015 New South Wales (NSW) Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (SPANS), a representative, cross-sectional school-based surveillance survey of weight and weight-related behaviors of children age 5 to 16 years living in NSW, Australia. The survey was based on a two-stage probability sample (school and student) with the probability of school selection being proportional to size of the school enrollment. Schools were sampled from each education sector (Government, Independent, Catholic) proportional to enrollment in that sector, and then all students from two randomly selected classes in each alternate school grade (Kindergarten, grades 2, 4, 6, 8, 10) were invited to participate. Sample size calculations were based on two primary outcomes: (i) achieving reliable estimates of point prevalence; and (ii) the detection of differences between demographically-defined groups (sub-groups). Sample size was calculated using p1 = 0.30 and p2 = 0.20 to detect a 10% difference in the prevalence between groups, with 80% power, alpha = 0.05 and design effect was 2.0 indicating 1252 children in each grade group.

The data were collected in schools by trained field teams from February 2015 to April 2015. Informed consent from each child’s parent/carer was a requirement for participation. Ethics approvals were granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, the NSW Department of Education and Training (DET) and the Catholic Education Offices for the Dioceses of Bathurst, Broken Bay, Canberra, Lismore, Maitland-Newcastle, Parramatta, and Wollongong.

Parents of children in Grades K (Kindergarten) 2 and 4 (i.e. child group) completed the questionnaire at home for their child. Adolescents in grades 6, 8 and 10 (i.e. adolescent group) completed the same questionnaire at school during the field team visit.

Outcomes

Height (m), weight (kg) and waist circumference (cm) were measured by the trained field teams at school. The Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) was calculated and children categorized using the International Obesity Taskforce cut offs as not overweight/obese or overweight/obese [21]. Waist-to-height Ratio (WHtR; cm/cm) was calculated as a measure of abdominal obesity where values ≥0.5 indicate an increased risk of cardio-metabolic outcomes and values <0.5 indicate a low risk for cardio-metabolic outcomes [22].

Individual behaviors

We assessed four individual behaviors that are associated with child obesity, including the frequency of (i) eating breakfast; (ii) eating dinner in front of the TV; (iii) eating meals or snacks from fast food/takeaway outlets and (iv) using electronic media (e.g. mobile phone or tablet or computer) during sleep time. For the analyses, each factor was dichotomized; breakfast as daily or not daily, eating dinner in front of the TV as <5 or ≥5 times/week, fast food consumption as <1 or ≥1 time/week and using e-media never/sometimes or usually.

Parenting influences

We assessed two parenting practices associated with child obesity using validated questions from the Child Feeding Questionnaire [23]. This included asking about (i) ad libitum snacking (i.e., At home, does your child/do you snack (on chips, biscuits, muesli bars etc.) and or drink soft drink whenever they like? (response categories; Yes or No, they/I have to ask first), and (ii) using food as a reward (i.e., How often do you/your parents offer your child/you sweets (lollies, ice cream, cake, biscuits) to your child as a reward for good behavior? (response categories; never/rarely, sometimes, usually). For the analyses, responses for this question were dichotomized as ‘never/sometimes’ and ‘usually’. The following question was used to determine how often limits were set on screen time, How often do you/your parents set limits/rules on your child’s/your screen-time (e.g., TV, DVDs, electronic games, tablets, mobile/smart phone)? (response categories; never/rarely, sometimes, usually). For the analyses, responses were dichotomized as ‘never/sometimes’ and ‘usually’.

Home environment factors

We assessed two factors in child’s homes that are consistently associated with overweight/obesity. The first was (i) Does your child/you have a TV in the bedroom? (response categories Yes or No). The second, related to the availability of soft drinks (sugar-sweetened beverages) in the home, was assessed by asking How often are soft drinks available in your home? (response categories never, sometimes, usually). For the analyses, responses were dichotomized as ‘never/sometimes’ and ‘usually’.

Covariates

Demographic information included child’s sex, date of birth, language spoken most at home and postcode of residence. Postcode of residence was a proxy measure of socioeconomic status (SES) using the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Socioeconomic Index for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage [24]. SEIFA summarizes census-obtained socioeconomic indicators for geographic areas including income, educational attainment, unemployment, and the proportion of people in unskilled occupations and were used to rank students into low, middle, and high tertiles of SES. Postcode was also used to categorize whether the child resided in a rural or urban location [25]. Language spoken most often at home was used to categorize children into English-speaking or non-English-speaking background [26]. Physical activity participation (a potential confounder) was determined using a validated question that is recommended for health surveillance surveys [27] which asks: How many days did the child/you engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for at least 60-min each day in the past 7-days? [28]. Physical activity participation was dichotomized according to the recommendation, <7 or 7-days (i.e., met recommendations or did not meet recommendations).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses were conducted using SPSS Complex Sample Analysis (Version 22 for Windows; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) to account for the complex sampling design. Post stratification weights were used to account for variations in response rates, along with cluster and stratification variables to account for the complex sampling design. Analyses were stratified by method of survey completion i.e. proxy report by parents for children in Grades K, 2 and 4 (child group) and self-report for adolescents in Grades 6, 8 and 10 (adolescent group). For the logistic regression analyses variables that showed significance (p < 0.05) on univariate analysis were entered into the model and a forward stepwise procedure was used to check the effect on the β coefficient. The final model was adjusted for age, sex, SES tertile, residential location (urban/rural), cultural background (English-speaking/other) and meeting daily physical activity recommendations (60 mins daily) or not.

Results

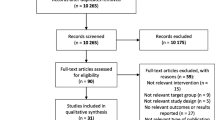

The sample comprised 3884 children (response rate = 68%; mean age 7.3 years) and 3671 adolescents (response rate = 51%; mean age 13.4 years) from 84 schools. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1 and indicate there were no socio-demographic differences between child and adolescent groups, however the odds of being overweight/obese were 32% higher among adolescents, compared with children (OR 1.32 95% CI: 1.11, 1.58).

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of weight-related individual behaviors, parent influences and home environment factors related to diet and screen-time, stratified by child and adolescent group. The figure shows that as children shift into adolescence there are clear and significant differences, with behaviors such as not eating breakfast daily (p < 0.001), having dinner in front of the TV ≥ 5 times week (p < 0.001) and using e-media during sleep time (p < 0.001) being more prevalent in adolescents. Compared with children, adolescents were more likely to have less parental restriction on snacking in the home (p < 0.001) and screen-time (p < 0.001), and to usually have soft drinks in the home (p < 0.001) and have a TV in the bedroom (p < 0.001) .

Table 2 shows the associations between individual behaviors, parent influences, and home environment and unhealthy weight status in children. The univariate analysis showed that not eating breakfast daily, eating fast food more than once a week, usually having soft drink (sugar sweetened beverages) available in the home, and having a TV in the bedroom were risk factors for overweight/obesity. After adjustment for covariates the odds of being overweight/obese were estimated to be 1.39 times higher for children who did not eat breakfast daily (p = 0.015), compared with children who ate breakfast daily and estimated to be 1.54 times higher if they had a TV in the bedroom (p = 0.006), compared with children who did not have TV in the bedroom. The same behavioral and home environment factors were associated with abdominal obesity in children (i.e., WHtR ≥0.5) but also included using e-media during sleep time and having no rules on snacking at home or screen-time. Once adjusted for covariates, the odds of having abdominal obesity were estimated to be 1.67 times higher for children who did not eat breakfast daily, compared with children who ate breakfast daily (p = 0.002), 1.67 times higher if they never had rules on screen-time (p = 0.007), and 1.80 times higher if they had a TV in the bedroom, compared with children who did not have TV in the bedroom (p = 0.001).

Table 3 shows the associations between individual behaviors, parent influences, and home environment and unhealthy weight status in adolescents. Factors which were significantly associated with being overweight/obese at a univariate level remained significant following adjustment of covariates. The adjusted odds of being overweight/obese were estimated to be 1.42 times higher for adolescents who do not eating breakfast daily (p = 0.001), 1.30 times higher if screen devices were usually used during sleep time (p = 0.022), 2.18 times higher when parents usually reward for good behavior with sweets (p = 0.036), and 1.29 higher when there were no rules on screen-time (p = 0.008). In contrast to children, only two factors were associated with abdominal obesity in adolescents at the univariate level, (not eating breakfast daily and having a TV in the bedroom) and once adjusted for covariates, not eating breakfast daily was the only significant risk factor (OR 1.37, p = 0.007).

The adjusted logistic regression models for predicting obesity/overweight measured by BMI and abdominal obesity measured by WHtR in children and adolescents are shown in Table 4. Among children, not eating breakfast daily and having a TV in the bedroom were the most significant predictors for both overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity. An additional predictor, not having limits on screen-time was a significant predictor of abdominal obesity in children. For adolescents, in addition to not eating breakfast daily, parenting practices such as rewarding good behavior with sweets and no rules on screen-time were significant predictors of obesity/overweight measured by BMI. For abdominal obesity in adolescents the only significant predictor was not eating breakfast daily.

An analysis of the significant factors was undertaken by socio-demographic sub-groups (data not shown). Children who do not eat breakfast daily were more likely to: be girls, compared with boys (OR 1.27 95% CI: 1.03, 1.57); come from low, compared with high SES neighborhoods (OR 2.82 95% CI: 1.73, 4.60); come from non-English-speaking, compared with English-speaking cultural backgrounds (OR 3.07 95% CI: 2.22, 4.25); and live in urban, compared with rural areas (OR 1.68 95% CI: 1.14, 2.47). Children with TV’s in the bedroom were more likely to come from low (OR 3.39 95% CI: 2.21, 5.20) and middle (OR 2.50 95% CI: 1.59, 3.94), compared with high SES neighborhoods; and girls were less likely to have screen-time rules imposed (OR 0.71 95% CI: 0.51, 0.99), compared with boys.

Adolescents who do not eat breakfast daily were more likely to be girls (OR 1.35 95% CI: 1.12, 1.63), come from low SES (OR 1.84 95% CI: 1.43, 2.37) and middle (OR 1.33 95% CI: 1.03, 1.73) SES neighborhoods, compared with high SES peers and come from non-English speaking, compared with English-speaking cultural backgrounds (OR 1.99 95% CI: 1.15, 3.43). Adolescents with TV’s in the bedroom were more likely to be boys (OR 2.09 95% CI: 1.64, 2.65), come from low (OR 2.11 95% CI: 1.49, 3.00) and middle (OR 1.87 95% CI: 1.31, 2.67), compared with high SES neighborhoods, come from English-speaking, compared with non-English speaking backgrounds (OR 2.15 95% CI: 1.52, 3.04) and live in urban, compared with rural areas (OR 1.54 95% CI: 1.06, 2.23). Adolescents from rural areas were more likely to never have screen-time rules imposed, compared with adolescents from urban areas (OR 1.31 95% CI: 1.02, 1.69); and adolescents with parents who reward their good behavior with sweets are more likely to be girls (OR 1.54 95% CI: 1.04, 2.28) and to come from non-English speaking backgrounds, compared with English-speaking cultural backgrounds (OR 1.73 95% CI: 1.16, 2.57).

Discussion

Our findings were based on a large representative sample of children and adolescents and show there are behaviors and practices within the home environment that are strongly associated with overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity in children and adolescents. Identifying these behaviors and practices and understanding how they are influenced in the family context is essential for the design of successful interventions. As with other studies, our findings show that the prevalence of many of these individual behaviors and practices is higher among adolescents [29, 30]. This is likely to reflect the increased autonomy during adolescence [31], however, prospective studies are required to ascertain whether exposure to, and adoption of these behaviors and practices during childhood influences their maintenance in adolescence. The findings illustrate that different family-based intervention strategies are needed for children and for adolescents, and these strategies are best directed at specific sub-groups of children and adolescents, specifically those from social disadvantage and non-English-speaking backgrounds.

A novel aspect of our study was to include abdominal obesity as an outcome. Compared with BMI measures of generalized obesity, abdominal obesity is more strongly correlated with metabolic risk factors [32] with evidence showing that abdominal obesity as indicated by WHtR ≥ 0.5 is a strong predictor of cardio-metabolic risk in children [33]. Although the prevalence of abdominal obesity in our study (13–14%) is much lower than US prevalence rates (~30–36%) [34] there is evidence that abdominal obesity has increased over the last 30-years in Australian children and adolescents [35] and warrants on-going surveillance given the associated cardio-metabolic risks. Interestingly, we found that not having breakfast daily and having a TV in the bedroom were the strongest predictors of both BMI measured overweight/obesity (using kg/m2) and abdominal obesity (using WHtR ≥0.5) in children. Among adolescents, not eating breakfast daily was the strongest predictor of overweight and obesity and abdominal obesity.

Our results are similar to other studies which show the importance of breakfast consumption [36] [9]. Recent data from the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE) showed that more frequent breakfast consumption was associated with lower BMI z-scores and body fat percentage compared with occasional and rare consumption [9]. The proposed mechanism for the protective effect of eating breakfast on obesity and overweight is that it may reduce snacking and consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods later in the day [37]. Skipping breakfast may also have long term effects. In a longitudinal Australian study of children age 9–15 years over 20 years, participants who reported skipping breakfast in both childhood and adulthood had larger waist circumferences, higher BMI, and poorer cardio-metabolic profiles than did those who reported eating breakfast at both time points [38]. A recent review of longitudinal studies also found similar results [39] and there may be other reasons to implement interventions to improve breakfast intake in children, beyond obesity and overweight, as an increased frequency of breakfast consumption has been consistently associated with improved academic performance [40]. International data also suggests that the prevalence children and adolescents consuming breakfast daily remains low [41], indicating the need for effective interventions to encourage daily healthy breakfasts and promote nutritious choices in these age groups.

In addition to not eating breakfast daily, having a TV in the bedroom was a major factor associated with overweight and obesity among children, and for adolescents not having limits set on screen-time was a significant factor. The reason may be two fold; children who have higher screen-time do less physical activity [42,43,44], and TV and internet food and beverage advertising has an influence on children’s and adolescent’s food choices [45]. Many studies have shown that excessive TV watching may favor concurrent consumption of energy-dense snacks and beverages [46, 47]. More frequent TV dinners were associated with more frequent consumption of soft drinks and snacks [48]. Screen-time has also been associated with obesity in both cross-sectional [49] and longitudinal studies [15]. Parenting practices can either facilitate or inhibit healthy eating and many studies have associated various parenting practices and styles with obesity and overweight [50] [12]. Rewarding good behavior with sweets suggests a permissive parenting style that may be a risk factor for obesity [51].

While our study had strengths including two outcome measures of unhealthy weight status and the large representative sample size of children and adolescents, there are limitations to consider when interpreting our findings. Because the data are cross-sectional no firm causal relationships can be determined. However, observational studies are an important information source for identifying sub-populations at greatest risk of poor health outcomes and would benefit most from health promoting interventions. Each construct was assessed by one question, and as such there may have been some reporting problems including recall issues and social desirability bias. Another limitation was the difference in the responder between the child and adolescent groups. Parents responded to the questionnaire on behalf of children and self-report measures were collected for adolescents. Due to these differences in responder, children and adolescents cannot strictly be compared.

Conclusions

Although interventions across multiple settings are required to address the rising prevalence of childhood obesity, the home is potentially the most important setting. The family and home environment are a major influence on child and adolescents eating and other lifestyle behaviors –not only because parents provide the food and environments, but the whole family influences attitudes, preferences and values that affect lifetime habits. Our findings suggest that four specific modifiable weight-related behaviors and practices that occur in the home; skipping daily breakfast, having a TV in the bedroom, not imposing rules on children and adolescent’s screen-time and rewarding adolescent’s good behavior with sweets are important factors to consider in home-based child obesity prevention interventions. Simple strategies such as reinforcing the importance of nutritious breakfasts and encouraging removal of TV’s from children’s bedrooms may be implemented immediately. Our findings also show that these behaviors and practices differ across sub-group populations and parents of children and adolescents from low SES neighborhoods and non-English-speaking backgrounds in particular would benefit from interventions that support changing these behaviors.

Change history

22 September 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- SEIFA:

-

Socioeconomic Index for Areas

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic Status

- SPANS:

-

School Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey

- TV:

-

Television

- WHtR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1121–6.

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77.

Yee SL, Williams-Piehota P, Sorensen A, Roussel A, Hersey J, Hamre R. The nutrition and physical activity program to prevent obesity and other chronic diseases: monitoring progress in funded states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A23.

Berge JM, Wall M, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parenting style as a predictor of adolescent weight and weight-related behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:331–8.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Larson NI, Fulkerson JA, Eisenberg ME, Story M. Family meals and adolescents: what have we learned from project EAT (eating among teens)? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1113–21.

Ostbye T, Malhotra R, Stroo M, Lovelady C, Brouwer R, Zucker N, Fuemmeler B. The effect of the home environment on physical activity and dietary intake in preschool children. Int J Obes. 2013;37:1314–21.

Grunseit AC, Taylor AJ, Hardy LL, King L. Composite measures quantify households' obesogenic potential and adolescents' risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e308–16.

Zakrzewski JK, Gillison FB, Cumming S, Church TS, Katzmarzyk PT, Broyles ST, Champagne CM, Chaput JP, Denstel KD, Fogelholm M, et al. Associations between breakfast frequency and adiposity indicators in children from 12 countries. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015;5:S80–8.

Hancox RJ, Poulton R. Watching television is associated with childhood obesity: but is it clinically important? Int J Obes. 2006;30:171–5.

Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:842–9.

Gerards SM, Kremers SP. The role of food parenting skills and the home food environment in Children's weight gain and obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4:30–6.

Pinard CA, Yaroch AL, Hart MH, Serrano EL, McFerren MM, Estabrooks PA. Measures of the home environment related to childhood obesity: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:97–109.

Vaughn AE, Ward DS, Fisher JO, Faith MS, Hughes SO, Kremers SP, Musher-Eizenman DR, O'Connor TM, Patrick H, Power TG. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: a content map to guide future research. Nutr Rev. 2016;74:98–117.

Maher C, Olds TS, Eisenmann JC, Dollman J. Screen time is more strongly associated than physical activity with overweight and obesity in 9- to 16-year-old Australians. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1170–4.

Carson V, Rosu A, Janssen I. A cross-sectional study of the environment, physical activity, and screen time among young children and their parents. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:61.

Gingold JA, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Excess screen time in US children: association with family rules and alternative activities. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53:41–50.

Askie LM, Baur LA, Campbell K, Daniels LA, Hesketh K, Magarey A, Mihrshahi S, Rissel C, Simes J, Taylor B, et al. The early prevention of obesity in CHildren (EPOCH) collaboration--an individual patient data prospective meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:728.

Redsell SA, Edmonds B, Swift JA, Siriwardena AN, Weng S, Nathan D, Glazebrook C. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions that aim to reduce the risk, either directly or indirectly, of overweight and obesity in infancy and early childhood. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:24–38.

Blake-Lamb TL, Locks LM, Perkins ME, Woo Baidal JA, Cheng ER, Taveras EM. Interventions for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:780–9.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:284–94.

Brambilla P, Bedogni G, Heo M, Pietrobelli A. Waist circumference-to-height ratio predicts adiposity better than body mass index in children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2013;37:943–6.

Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the child feeding questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–10.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia 2011.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS)- Remoteness Structure. Canberra 2013.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Australian Standard Classification of Languages (ASCL) 2011.

Active Healthy Kids Australia: Do our kids have all the tools? The 2016 Active Healthy Kids Australia Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Young People. Adelaide, South Australia: Active Healthy Kids Australia; 2016.

Prochaska JJSJ, Long B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:554–9.

Cislak A, Safron M, Pratt M, Gaspar T, Luszczynska A. Family-related predictors of body weight and weight-related behaviours among children and adolescents: a systematic umbrella review. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:321–31.

Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:743–60. quiz 761-742

Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:S40–51.

Kelishadi R, Mirmoghtadaee P, Najafi H, Keikha M. Systematic review on the association of abdominal obesity in children and adolescents with cardio-metabolic risk factors. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:294–307.

Khoury M, Manlhiot C, McCrindle BW. Role of the waist/height ratio in the cardiometabolic risk assessment of children classified by body mass index. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:742–51.

Xi B, Mi J, Zhao M, Zhang T, Jia C, Li J, Zeng T, Steffen LM, Public Health Youth C, Innovative Study Group of Shandong U: Trends in abdominal obesity among U.S. children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 134:e334–e339.

Hardy LL, Mihrshahi S, Gale J, Drayton BA, Bauman A, Mitchell J. 30-year trends in overweight, obesity and waist-to-height ratio by socioeconomic status in Australian children, 1985 to 2015. Int J Obes. 2017;41:76–82.

Szajewska H, Ruszczynski M. Systematic review demonstrating that breakfast consumption influences body weight outcomes in children and adolescents in Europe. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:113–9.

Timlin MT, Pereira MA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: project EAT (eating among teens). Pediatrics. 2008;121:e638–45.

Smith KJ, Gall SL, McNaughton SA, Blizzard L, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Skipping breakfast: longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the childhood determinants of adult health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1316–25.

Blondin SA, Anzman-Frasca S, Djang HC, Economos CD. Breakfast consumption and adiposity among children and adolescents: an updated review of the literature. Pediatr Obes. 2016;

Adolphus K, Lawton CL, Dye L. The effects of breakfast on behavior and academic performance in children and adolescents. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:425.

Lazzeri G, Ahluwalia N, Niclasen B, Pammolli A, Vereecken C, Rasmussen M, Pedersen TP, Kelly C. Trends from 2002 to 2010 in daily breakfast consumption and its socio-demographic correlates in adolescents across 31 countries participating in the HBSC study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151052.

Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C. Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among young children: a systematic review. J Obes. 2015;2015:546925.

Huhman M, Lowry R, Lee SM, Fulton JE, Carlson SA, Patnode CD. Physical activity and screen time: trends in U.S. children aged 9-13 years, 2002-2006. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:508–15.

Fakhouri TH, Hughes JP, Brody DJ, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Physical activity and screen-time viewing among elementary school-aged children in the United States from 2009 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:223–9.

Hebden LA, King L, Grunseit A, Kelly B, Chapman K. Advertising of fast food to children on Australian television: the impact of industry self-regulation. Med J Aust. 2011;195:20–4.

Rey-Lopez JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Repasy J, Mesana MI, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Kafatos A, Huybrechts I, Cuenca-Garcia M, Leon JF, et al. Food and drink intake during television viewing in adolescents: the healthy lifestyle in Europe by nutrition in adolescence (HELENA) study. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:1563–9.

Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, Varady A, Robinson TN. Children's food consumption during television viewing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:1088–94.

Lipsky LM, Haynie DL, Liu D, Chaurasia A, Gee B, Li K, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton B: Trajectories of eating behaviors in a nationally representative cohort of U.S. adolescents during the transition to young adulthood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015, 12:138.

Wethington H, Pan L, Sherry B: The association of screen time, television in the bedroom, and obesity among school-aged youth: 2007 National Survey of Children's health. J Sch Health 2013, 83:573–581.

Shier V, Nicosia N, Datar A. Neighborhood and home food environment and children's diet and obesity: evidence from military personnel's installation assignment. Soc Sci Med. 2016;158:122–31.

Sleddens EF, Gerards SM, Thijs C, de Vries NK, Kremers SP. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: a review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e12–27.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the schools and students for their participation.

Funding

SPANS 2015 was funded by the NSW Ministry of Health. The authors wish to thank the schools and students for their participation. This work was completed while BAD was employed as a trainee on the NSW Biostatistics Training Program funded by the NSW Ministry of Health. He undertook this work whilst based at the Prevention Research Collaboration, Sydney School of Public Health.

Availability of data and materials

The data is not available. The data is owned by the NSW Ministry of Health.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM and LLH conceptualised the manuscript, SM conducted the analysis, and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. BAD participated in conceptualising the statistical analysis. LLH, BAD and AB provided critical review of drafts. LLH was chief investigator of the survey and was responsible for developing the instruments and overseeing management of the survey.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethics approvals were granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, the NSW Department of Education and Training (DET) and the NSW Catholic Education Commission. Informed consent from each child’s parent/carer was a requirement for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4709-6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mihrshahi, S., Drayton, B.A., Bauman, A.E. et al. Associations between childhood overweight, obesity, abdominal obesity and obesogenic behaviors and practices in Australian homes. BMC Public Health 18, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4595-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4595-y