Abstract

Background

The relationship between pathological factors and lymph node metastasis of pathological stage early gastric cancer has been extensively investigated. By contrast, the relationship between preoperative factors and lymph node metastasis of clinical stage early gastric cancer has not been investigated. The present study was to investigate discrepancies between preoperative and postoperative values.

Methods

From January 2011 to December 2013, 1042 patients with clinical stage early gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy were enrolled. Preoperative and postoperative values were collected for subsequent analysis. Receiver operating characteristics curves were computed using independent predictive factors.

Results

Several discrepancies were observed between preoperative and postoperative values, including existence of ulcer, gross type, and histology (all McNemar p-values were <0.001). Multivariate analyses identified the following independent predictive factors for lymph node metastasis: postoperative values including age (p = 0.002), tumor size (p < 0.001), and tumor depth (p < 0.001); preoperative values including age (p = 0.017), existence of ulcer (p = 0.037), tumor size (p = 0.009), and prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in computed tomography scans (p = 0.002). These postoperative and preoperative independent predictive factors produced areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves of 0.824 and 0.660, respectively.

Conclusions

Surgeons need to be aware of limitations in preoperative predictions of the presence of lymph node metastasis for clinical stage early gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the world and the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. The incidence of early gastric cancer is increasing especially in Korea and Japan because of improvements in endoscopic diagnosis and the national screening systems [2–5]. In Korea and Japan, early gastric cancer has an excellent prognosis after surgical treatment, with 5-year survival rates of more than 90 % [5]. Lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer patients has been reported to occur in approximately 10–15 % of cases, and it is one of the strongest prognostic factors for patients with early gastric cancer [1, 6–8].

The final result of the Dutch trial concluded that gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy is a standard surgical procedure for patients with gastric cancer [9]. According to the Japanese guideline, which was established based on numerous pathological data, standard D2 lymphadenectomy is recommended for clinical stage early gastric cancer patients with lymph node metastasis, and more limited lymphadenectomy such as D1 or D1+ can be options for patients with clinical stage early gastric cancer without lymph node metastasis [10]. However, preoperative prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis for clinical stage early gastric cancer patients is challenging, and preoperative diagnosis carries some degree of inaccuracy, so surgeons always need to consider the possibility of overstaging and understaging. Understaging leads to insufficient treatment, which may exhaust the chance of a cure, whereas overstaging leads to overtreatment, which may increase morbidity and mortality and affect the postoperative quality of life. Although the relationship between pathological factors and lymph node metastasis of pathological stage early gastric cancer has been extensively investigated, the relationship between preoperative factors and lymph node metastasis of clinical stage early gastric cancer has not been investigated [11–15]. The level of discrepancy between preoperative and postoperative diagnostic values also is not well understood.

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the discrepancies between preoperative and postoperative diagnostic values and the relationship between preoperative diagnostic values and lymph node metastasis of clinical stage early gastric cancer.

Methods

Patients and data collection

From January 2011 to December 2013, 1093 patients with clinical stage early gastric cancer underwent gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy at Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea. Clinical stage early gastric cancer is defined as a lesion which is preoperatively diagnosed as confined to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of the regional lymph node metastasis. Diagnosis is primarily performed using esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and computed tomography (CT) scans [16]. Patients with the following factors were excluded: no EGD (n = 16) or CT scan report (n = 2) in our hospital, CT scans performed after endoscopic submucosal dissection (n = 15), incomplete pathological report (n = 9), remnant gastric cancer (n = 5), and multiple lesions (n = 4). A total of 1042 patients were enrolled into the present cohort. The following preoperative values of patients were collected: age, gender, body mass index, tumor size, existence of ulcer, gross type, histology, tumor location, and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio. EGD and CT scans were performed for all patients. Tumor detectability and prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis by CT scans were recorded, and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was performed for some patients to examine tumor depth and the presence of perigastric lymph node metastasis. The following postoperative values of patients were collected: tumor size, existence of ulcer, gross type, histology, tumor location, pathological tumor depth, and lymph node metastasis. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital, which waived the need for written informed consent from the participants (4-2014-0971).

Preoperative diagnostic methods

Preoperative diagnosis of clinical stage early gastric cancer was conducted through preoperative examinations such as EGD, EUS, and CT scans. Tumor size was measured using both EGD and EUS. If lesion size was measured using both EGD and EUS, the larger measurement was recorded as the representative tumor size [17, 18].

Preoperative CT scan was performed with a multi-detector row CT scanner (Sensation 16 or 64; Siemens Medical Solutions, Germany). Patients were instructed to fast for at least 4 h before the examination. Patients were prepared by injecting 10 mg butylscopolamine bromide and giving 2 packs of effervescent granules for gastric hypotonia and distention. Scanning was performed from the diaphragm to the symphysis pubis, with the patient in a supine position. A dose of 120–150 ml contrast medium was administered intravenously at a rate of 3–4 ml/s using a power injector, and the images of arterial and portal phases were obtained. CT scanning parameters were as follows: beam collimation, 0.75 mm × 16 or 0.6 mm × 64; kVp/effective mA, 120/160; and gantry rotation time, 0.5 s. Axial and coronal images were reconstructed at 3 mm interval with a slice thickness of 3 mm. If thickening or enhanced gastric mucosa was observed, it was regarded as a detectable tumor. Prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis was established if the node met two or more of the following criteria: (1) ≥8 mm diameter in the short-axis, (2) round shape, (3) enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT scans, or (4) necrosis.

EUS was performed with radial scanning echoendoscopy at 5–12 MHz (GF-UE260; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The assessment of T-stage with EUS was based on the generally accepted 5-layer sonographic structure of the gastric wall. Early gastric cancer lesions were located within the first three layers, whereas advanced gastric cancer tumors invaded to the fourth and fifth layers. The assessment of N-stage with EUS was based on the existence of metastatic perigastric lymph nodes. Prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis was established if the node met two or more of the following criteria: (1) ≥10 mm in the short-axis, (2) round shape, (3) hypoechoic pattern, or (4) smooth border [19].

Statistical methods

Continuous values were analyzed with mean, standard deviation, and range. Correspondence between preoperative and postoperative values was analyzed using McNemar and Kappa values. Univariate analyses were performed using logistic regression analysis. Multivariate analyses were performed using multiple logistic regression models with the forward likelihood ratio method. Pearson’s coefficient correlation was performed to identify the correlation between two continuous values. Linear regression analysis was performed to compensate missing preoperative tumor size based on postoperative tumor size. A p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Receiver operating characteristics curves were obtained by the probability of finally selected multivariate logistic regression models and the presence of lymph node metastasis; the area under the curve, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated using R version 3.0.1 (http://www.R-project.org/) using the “pROC” and “Optimal Cutpoints” packages and the cutoff point was determined by the Youden method [20].

Results

Patient data

Baseline characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 58.0 years, 625 patients (60.0 %) were male, and 417 patients (40.0 %) were female. In preoperative CT scans, the tumors of 210 patients (20.2 %) were detectable, and 42 patients (4.0 %) were suspected to have lymph node metastasis. Pathological evidence indicated that 74 patients (7.1 %) had lymph node metastasis, and 81 patients (7.8 %) were diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer even though each lesion was considered preoperatively as early gastric cancer.

Several discrepancies were observed between preoperative and postoperative diagnostic values including existence of ulcer, gross type, and histology (McNemar p-values were <0.001 for all results; κ and p for each diagnostic value were 0.082 and 0.001, 0.171 and <0.001, and 0.528 and <0.001, respectively; Table 2). The tumor size of each case was measured using EGD only in 299 cases (28.7 %), using EUS only in 147 cases (14.1 %), and using both EGD and EUS in 332 cases (31.9 %). Overall, the tumor size of 778 cases (74.7 %) was recorded as preoperative combined size. Correlation coefficients (r value) between pathological and preoperative tumor size using EGD (n = 631), EUS (n = 479), and combined size (n = 778) were 0.330, 0.264, and 0.325, respectively. Linear regression analysis of the relationship between pathological and preoperative combined tumor size also was performed [preoperative combined tumor size (mm) = 13.049 + 0.206 × Pathological tumor size (mm); p < 0.001, R2=0.110; Fig. 1). Missing data for preoperative combined tumor sizes [263 cases (25.2 %)] were compensated using the obtained formula (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Postoperative and preoperative predictive factors for lymph node metastasis

Univariate analysis for postoperative values indicated that age (p = 0.025), gross type (p < 0.001), histology (p = 0.001), tumor size (p < 0.001), and tumor depth (p < 0.001) were significant predictive factors for lymph node metastasis. Multivariate analysis indicated that age (p = 0.002), tumor size (p < 0.001), and tumor depth (p < 0.001) were independent predictive factors (Table 3).

Univariate analysis for preoperative values indicated that age (p = 0.025), existence of ulcer (p = 0.041), tumor size (p = 0.010), and prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in CT scans (p = 0.002) were significant predictive factors for lymph node metastasis. Multivariate analysis indicated that age (p = 0.017), existence of ulcer (p = 0.037), tumor size (p = 0.009), and prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in CT scans (p = 0.002) were independent predictive factors for lymph node metastasis (Table 4).

Association between CT scans and EUS results and lymph node metastasis

The correspondence between preoperative CT scan and EUS results and pathological lymph node metastasis is shown in Table 5. CT scan results were obtained from all enrolled patients, whereas EUS results were available from 491 patients (47.1 %). Prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in CT scan was the only significant predictor for lymph node metastasis (p = 0.002). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, overstaging, and understaging of preoperative prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis by CT scan were 12.2, 96.6, 21.4, 93.5, 3.2, and 6.2 %, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

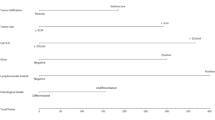

Receiver operating characteristics curves using independent predictive factors

Receiver operating characteristics curves were constructed by the probability of the finally selected logistic regression models in each postoperative (the model including age, tumor size, and T-stage, Table 3) and preoperative (the model including age, ulcer, tumor size, and prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in CT scan, Table 4) values and the event (lymph node metastasis). Figure 2 depicted the predictive performance of both multivariate models in postoperative and preoperative values.

Receiver operating characteristics were analyzed for area under the curve, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value using postoperative independent predictive factors, and were 0.824, 81.1 %, 71.4 %, 2.0 %, and 82.2 %, respectively. By contrast, area under the curve, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of receiver operating characteristics using preoperative independent predictive factors were 0.660, 68.9 %, 54.6 %, 4.3 %, and 89.6 %, respectively.

Discussion

We analyzed preoperative and postoperative predictive factors for the presence of lymph node metastasis in clinical stage early gastric cancer, and created prediction models using both independent preoperative and postoperative factors. The prediction model using postoperative independent factors was quite reliable (area under the curve = 0.812), whereas the one using preoperative factors was less reliable (area under the curve = 0.660). The prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis in preoperative CT scan had the highest odds ratio among independent preoperative predictive factors; however, 3.2 % of patients were understaged and 6.2 % of patients were overstaged. Thus, CT scan is not reliable enough for prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis, although it appears to be the most reliable tool in current practice.

One possible reason why preoperative values are not reliable enough to accurately predict the presence of lymph node metastasis is due to the discrepancy between preoperative and postoperative values. Postoperative tumor size is determined by measuring formalin-fixed specimens, whereas preoperative size is estimated from EGD or EUS results. The lesion border can be ambiguous, and it is challenging to accurately identify the lesion extent preoperatively. Tumor size measurement depends on the expertise of endoscopists. Postoperative specimens are fixed with formalin, which induces shrinkage of pathological samples. These factors often lead to discrepancies between preoperative and postoperative tumor size measurements [17, 18]. Histological heterogeneity is one of the distinctive characteristics of gastric cancer. There was usually a discrepancy between preoperative and postoperative histology results, which we also confirmed in the present study. The amount of tissue obtained through biopsy is usually limited, and it is taken primarily from mucosa, so the biopsy histology does not always represent the most dominant histology type of the lesion. According to the literature, the reported percentage of histological discrepancy in early gastric cancer ranges from 16.3 to 53.7 % [21–25]. This can explain why postoperative histology was significant for lymph node metastasis in the present study, whereas preoperative histology was not. Pathological T-stage is generally related to lymph node metastasis, which is why it is included in endoscopic submucosal dissection criteria [11]. If an accurate and precise preoperative assessment of tumor depth can be achieved, it would be helpful for predicting the presence of lymph node metastasis. However, this is still challenging, and preoperative diagnosis of tumor depth inherently contains some degree of inaccuracy even using EUS [26, 27].

Lymph node size is a common measurement when lymph nodes are assessed using CT scan. However, Monig et al. reported that mean diameter of metastatic lymph node was 6.0 mm, whereas that of tumor-free nodes was 4.1 mm. They also reported that the percentage of metastatic lymph nodes larger than 6 and 10 mm were 45 and 9.7 %, respectively, with a 10 % shrinkage factor during laboratory preparation [28]. A report by Park et al. on preoperative CT scans of pathologically lymph node metastatic-free patients concluded that lymph nodes larger than 8 mm in the short-axis can be detected in 14.9 % of early gastric cancer patients and 44.2 % of advanced gastric cancer patients. Those reports suggest that prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis using CT scans cannot be completely accurate as long as criteria of the presence of lymph node metastasis include the lymph node size.

Alternative methods for prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis include fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and EUS. FDG-PET is a preoperative diagnostic tool in various fields including gastric cancer. However, FDG-PET has low sensitivity, and is not currently a reliable tool for predicting the presence of lymph node metastasis and identifying early gastric cancer [29–31]. A meta-analysis by Cardoso et al. reported that the pooled accuracy of N-stage prediction by EUS was 64 % (95 % confidence interval = 43 − 84 %) [27]. EUS also was not a significantly reliable predictor in the current study. Therefore, FDG-PET and EUS cannot completely overcome the current lack of prediction accuracy.

Another method for prediction of the presence of lymph node metastasis is required. Sentinel node navigation surgery is a possible and promising solution. Application of sentinel node navigation surgery using dye-based or radioisotope-based techniques has been explored in the gastric cancer field [32–34]. Sentinel node navigation surgery using near-infrared imaging together with indocyanine green injection has been introduced to several fields including gastric cancer [35–39]. Optimized sentinel node navigation surgery should allow accurate detection of sentinel lymph nodes and real-time observation of lymphatic flow. However, a standard method for sentinel node navigation surgery has not yet been established, and the possibility of skip metastasis should always be considered. A multicenter randomized prospective clinical trial of sentinel node navigation surgery is ongoing in Korea to validate sentinel node navigation surgery for clinical application (NCT number 01804998) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT018r04998?term=sentinel+and+gastric+cancer&rank=3). Therefore, a surgical strategy should be considered for each patient on a case-by-case basis according to current guidelines until accurate preoperative diagnostic methods for the presence of lymph node metastasis can be established.

The present study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study. Second, there was a selection bias because clinical stage early gastric cancer patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection were not included unless their tumors met exclusion criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection and required subsequent surgery. Third, precise information regarding preoperative tumor depth was not fully available because EUS was not performed for all patients in the cohort. Fourth, the preoperative tumor sizes of some patients were missing, although they were compensated using linear regression analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, obvious discrepancies exist between preoperative and postoperative diagnostic values for the presence of lymph node metastasis for early gastric cancer. The prediction sensitivity and positive predictive value of the presence of lymph node metastasis using CT scan is low, but it currently remains as the most reliable tool. Predicting the presence of lymph node metastasis of clinical stage early gastric cancer is still challenging, and surgeons need to be aware of limitations in preoperative prediction accuracy of the presence of lymph node metastasis for early gastric cancer.

Abbreviations

- EGD:

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography

- FDG-PET:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359.

Hamashima C, Shibuya D, Yamazaki H, Inoue K, Fukao A, Saito H, et al. The Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(4):259–67.

Choi KS, Jun JK, Lee HY, Park S, Jung KW, Han MA, et al. Performance of gastric cancer screening by endoscopy testing through the National Cancer Screening Program of Korea. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(8):1559–64.

Pasechnikov V, Chukov S, Fedorov E, Kikuste I, Leja M. Gastric cancer: prevention, screening and early diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(38):13842–62.

Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16(1):1–27.

An JY, Baik YH, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer with submucosal invasion: analysis of a single institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):749–53.

Roviello F, Rossi S, Marrelli D, Pedrazzani C, Corso G, Vindigni C, et al. Number of lymph node metastases and its prognostic significance in early gastric cancer: a multicenter Italian study. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94(4):275–80. discussion 274.

Pelz J, Merkel S, Horbach T, Papadopoulos T, Hohenberger W. Determination of nodal status and treatment in early gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(9):935–41.

Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(5):439–49.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14(2):113–23.

Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3(4):219–25.

Lee JH, Choi IJ, Han HS, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Yoon HM, et al. Risk of lymph node metastasis in differentiated type mucosal early gastric cancer mixed with minor undifferentiated type histology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1813.

Kim BS, Oh ST, Yook JH. Signet ring cell type and other histologic types: differing clinical course and prognosis in T1 gastric cancer. Surgery. 2014;155(6):1030–5.

Son SY, Park JY, Ryu KW, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Cho SJ, et al. The risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer patients who underwent endoscopic resection: is the minimal lymph node dissection applicable? A retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(9):3247–53.

Takizawa K, Ono H, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Hasuike N, Matsubayashi H, et al. Risk of lymph node metastases from intramucosal gastric cancer in relation to histological types: how to manage the mixed histological type for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16(4):531–6.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14(2):101–12.

Shim CN, Song MK, Kang DR, Chung HS, Park JC, Lee H, et al. Size discrepancy between endoscopic size and pathologic size is not negligible in endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(7):2199–207.

Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Endoscopic estimation of tumor size in early gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(8):2329–36.

Park CH, Park JC, Kim EH, Jung DH, Chung H, Shin SK, et al. Learning curve for EUS in gastric cancer T staging by using cumulative sum analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:898.

R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing V; 2014.

Min BH, Kang KJ, Lee JH, Kim ER, Min YW, Rhee PL, et al. Endoscopic resection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer: focusing on histologic discrepancies between forceps biopsy-based and endoscopic resection specimen-based diagnosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(10):2536–43.

Lee CK, Chung IK, Lee SH, Kim SP, Lee TH, Kim HS, et al. Is endoscopic forceps biopsy enough for a definitive diagnosis of gastric epithelial neoplasia? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(9):1507–13.

Park JS, Hong SJ, Han JP, Kang MS, Kim HK, Kwak JJ, et al. Early-stage gastric cancers represented as dysplasia in a previous forceps biopsy: the importance of clinical management. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(2):170–5.

Takao M, Kakushima N, Takizawa K, Tanaka M, Yamaguchi Y, Matsubayashi H, et al. Discrepancies in histologic diagnoses of early gastric cancer between biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15(1):91–6.

Won CS, Cho MY, Kim HS, Kim HJ, Suk KT, Kim MY, et al. Upgrade of lesions initially diagnosed as low-grade gastric dysplasia upon forceps biopsy following endoscopic resection. Gut Liver. 2011;5(2):187–93.

Mouri R, Yoshida S, Tanaka S, Oka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography in determining the depth of invasion and indication for endoscopic treatment of early gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(4):318–22.

Cardoso R, Coburn N, Seevaratnam R, Sutradhar R, Lourenco LG, Mahar A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the utility of EUS for preoperative staging for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S19–26.

Monig SP, Zirbes TK, Schroder W, Baldus SE, Lindemann DG, Dienes HP, et al. Staging of gastric cancer: correlation of lymph node size and metastatic infiltration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(2):365–7.

Dassen AE, Lips DJ, Hoekstra CJ, Pruijt JF, Bosscha K. FDG-PET has no definite role in preoperative imaging in gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(5):449–55.

Mochiki E, Kuwano H, Katoh H, Asao T, Oriuchi N, Endo K. Evaluation of 18 F-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography for gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2004;28(3):247–53.

Mukai K, Ishida Y, Okajima K, Isozaki H, Morimoto T, Nishiyama S. Usefulness of preoperative FDG-PET for detection of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9(3):192–6.

Lee SE, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. Sentinel node mapping and skip metastases in patients with early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(3):603–8.

Mitsumori N, Nimura H, Takahashi N, Kawamura M, Aoki H, Shida A, et al. Sentinel lymph node navigation surgery for early stage gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(19):5685–93.

Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kook MC, Lee JY, Kim CG, Choi IJ, et al. Feasibility of laparoscopic sentinel basin dissection for limited resection in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(5):331–5.

Khullar O, Frangioni JV, Grinstaff M, Colson YL. Image-guided sentinel lymph node mapping and nanotechnology-based nodal treatment in lung cancer using invisible near-infrared fluorescent light. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;21(4):309–15.

Schaafsma BE, Verbeek FP, Peters AA, van der Vorst JR, de Kroon CD, van Poelgeest MI, et al. Near-infrared fluorescence sentinel lymph node biopsy in vulvar cancer: a randomised comparison of lymphatic tracers. BJOG. 2013;120(6):758–64.

Schaafsma BE, Verbeek FP, Elzevier HW, Tummers QR, van der Vorst JR, Frangioni JV, et al. Optimization of sentinel lymph node mapping in bladder cancer using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(7):845–50.

Nimura H, Narimiya N, Mitsumori N, Yamazaki Y, Yanaga K, Urashima M. Infrared ray electronic endoscopy combined with indocyanine green injection for detection of sentinel nodes of patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91(5):575–9.

Ishikawa K, Yasuda K, Shiromizu A, Etoh T, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Laparoscopic sentinel node navigation achieved by infrared ray electronic endoscopy system in patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(7):1131–4.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (1020390, 1320360).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None of the authors have conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

MN and YYC collected data, carried out statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JYA analyzed the data and revised the manuscript, SHS, HBS, HJB, and SL collecting the data and revised the manuscript. HC revised the manuscript and gave the information of preoperative diagnosis based on his expertise. HIK, JHC, and WJH revised the manuscript. SHN participated in the design of the study, analyze the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Masatoshi Nakagawa and Yoon Young Choi contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Scheme showing how tumor sizes were obtained in the present study. EGC, early gastric cancer; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; CT, computed tomography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography. (TIF 73 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Scheme showing the relationship between clinical and pathological lymph node assessments. cEGC: clinical stage early gastric cancer; cLN, clinical stage lymph node; pLN: pathological stage lymph node. (TIF 88 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakagawa, M., Choi, Y.Y., An, J.Y. et al. Difficulty of predicting the presence of lymph node metastases in patients with clinical early stage gastric cancer: a case control study. BMC Cancer 15, 943 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1940-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1940-3