Abstract

Background

Postpartum depression (PPD) is considered an important public health problem, and early recognition of PPD in pregnant and lactating women is critical. This study investigated the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) toward PPD among pregnant and lying-in women.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Binzhou Medical University Hospital between September 2022 and November 2022 and included pregnant and lying-in women as study participants. A questionnaire was designed by the researchers that included demographic data and knowledge, attitude, and practice dimensions. Correlations between knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. Factors associated with practice scores were identified by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

All participants scored 6.27 ± 2.45, 36.37 ± 4.16, and 38.54 ± 7.93 93 from three sub-dimensions of knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding PPD, respectively, with statistical differences in the three scores by age, education, and job status (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between maternal (6.24 ± 2.34, 36.67 ± 3.82 and 38.31 ± 7.27, respectively) and pregnant women (6.30 ± 2.49, 36.00 ± 4.53 and 38.83 ± 8.69, respectively) in the total scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice dimensions. According to the results of multivariate logistic regression, the knowledge (OR = 1.235[1.128–1.353], P < 0.001) and attitude (OR = 1.052[1.005–1.102], P = 0.030) dimension scores were factors influencing the practice dimension scores.

Conclusion

The KAP of pregnant and lying-in women toward PPD is low. This study suggests that maternal awareness of PPD should be increased through the knowledge and attitudinal dimensions. Preventing PPD in pregnant and lying-in women can be achieved by improving both dimensions, thus enhancing practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pregnancy is a complex process that can lead to dramatic changes in female’s physical, psychological, and social roles. Since pregnancy and birth-giving are both major life events and traumatic processes, postpartum is often considered to be the most risky stage for women to develop depression [1, 2]. Postpartum depression (PPD) is a cross-disciplinary disorder between obstetrics and psychology, which not only has a negative impact on the health of a lying-in woman and her marriage and family but also on breastfeeding, the mother-infant relationship, and the growth& development and emotional behavior of the infant. In more serious cases, infanticide and suicidal tendencies or behaviors may even occur, causing great harm to the mother’s family and society [3, 4].

Risk factors for PPD have been discussed more in previous studies. Pregnant women’s psychophysiological disorders can influence PPD. A meta-analysis by Liu et al. [5] concluded that PPD is relatively higher in developing countries and that gestational diabetes and a history of depression were considered risk factors. In addition, the influence of family on postnatal depression is equally essential. Xie et al. [6] concluded that postnatal family support, especially from the husband, is an essential protective factor for postnatal depression. Poreddi et al. [7] investigated family members in terms of both knowledge and attitudes and concluded that there is an urgent need to address misconceptions and negative stereotypes about postnatal depression among family members. Since there is still a COVID-19 pandemic and the prevalence and odds of PPD are significantly higher [8], there is a need for greater awareness and guidance on PPD.

A knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) survey is a structured survey method that can be used to investigate the current state of specific people (i.e., pregnant and lying-in women) toward a specific subject (i.e., PPD) [9]. The practice represents the various behaviors and actions taken by the surveyed people toward the specific subject. Previous studies examined the KAP toward related subjects in different populations. Temtanakitpaisan et al. [10] investigated pregnant women’s awareness of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) using a KAP questionnaire. A questionnaire revealed that women perceive that PFMT impacts their mental health and quality of life positively. Aiga et al. [11] used a KAP questionnaire to assess the effectiveness of maternal and child health manuals to intervene in maternal behavior change. Using this questionnaire allowed for greater effectiveness of maternal and child health manuals. KAP surveys are becoming increasingly important as they can enhance the views and perceptions of specific people about certain things. No data are available about the maternal awareness of PPD through the three KAP dimensions. In our study, a high-reliability and validity questionnaire was designed to investigate the three dimensions of maternal awareness. Furthermore, the practice dimension was used to guide maternal awareness to reduce the occurrence of PPD.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2022 and November 2022 at Binzhou Medical University Hospital and included pregnant (any gestational age) and lying-in women who volunteered to participate in this study as participants. Pregnant women were defined as reproductive-age women with a history of sexual activity, amenorrhea or menstrual abnormalities, positive blood or urine hCG test indicating pregnancy, and ultrasound findings of intrauterine gestational sac or embryo. The lying-in women were those with postpartum hospitalization or attending follow-up visits within 42 days after delivery. This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University Hospital (approval no. LW-37), and informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Procedures

Based on Expert Consensus on Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Depression and previously published studies [12–14], the KAP questionnaire was self-designed and included four dimensions: (1) demographic data of the participants; (2) knowledge dimension, consisting of 10 questions (items K4 and K8 were incorrect statements), scored 1 point for correct answers and 0 points for wrong or unclear answers, with total scores ranging from 0 to 10 points; (3) attitude dimension, containing 10 questions scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very positive (5 points) to very negative (1 point), with total scores ranging from 10 to 50 points; (4) practice dimension, including 11 items (item P1 included seven subitems) scored using 5-point Likert scale ranging from always (5 points) to never (1 point), with total scores ranging from 11 to 55 points. Higher scores indicated better KAP.

A small pre-test (50 copies) was conducted before the formal launch, and Cronbach’s α was 0.9266, suggesting a high internal consistency. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are now shown in Supplementary Figure S1 ((CFI = 0.817 (> 0.800 is good); IFI = 0.818 (> 0.800 is good); RMSEA = 0.069 (< 0.080 is good); CMIN/DF = 3.859 (> 1; 1–3 is excellent, 3–5 is good)), indicating that the questionnaire has good reliability.

Online e-questionnaires are created through the Wen-Juan-Xing online platform in China (https://www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx), the questionnaires were distributed, and the data were collected from anonymous participants through Moments forwarding and WeChat group promotion. In order to ensure the quality and completeness of the questionnaire results, each IP address can only be used once for submission. Each question was compulsory. All questionnaires were checked for completeness, consistency, and validity by members of the research team.

Statistical analysis

Stata 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the distribution of the continuous variables, and most of them were not conforming to a normal distribution. They were presented as median (P25, P75) and analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. Age was presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Categorical data were expressed as n (%). Pearson’s correlation was used to analyze the correlation between knowledge scores, attitude scores, and practice scores. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to analyze the factors influencing practice. Sufficient knowledge, positive attitude, and proactive practice were defined as scores exceeding 70% of the total score for each respective dimension [15]. All statistical tests were performed using two-sided tests, and P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In the absence of relevant literature on pelvic floor dysfunction and pelvic floor ultrasound in our population, the sample size for the study was calculated with an anticipated proportion of mask-wearing practice as 50%, at a 95% confidence level and 5% error margin the required sample size of 384 was calculated. Considering a 70% response rate, at least 549 participants were needed to be included [16].

Results

Baseline and KAP scores in pregnant and lying-in women

Five hundred ninety-four pregnant women completed the questionnaire, with most participants aged 25–35 years (78.5%), nearly two-thirds of whom were urban residents, and more than two-thirds had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The total score of the knowledge dimension for all participants was 6.27 ± 2.45, with statistical differences (p < 0.05) for different age, places of residence, education, work status, and para; the total score of the attitude dimension was 36.37 ± 4.16, with statistical differences for different age, residence, education, work status, gravida, para, and current gestational age (p < 0.05), the total score of the practice dimension was 38.54 ± 7.93, and there were statistical differences in the scores of different age, education, and work status (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

The total scores for the three dimensions of knowledge, attitude, and practice were 6.24 ± 2.43, 36.67 ± 3.82 and 38.31 ± 7.27 for pregnant women and 6.30 ± 2.49, 36.00 ± 4.53 and 38.83 ± 8.69 for lying-in women, respectively, and there was no statistical difference between the total scores of pregnant women and mothers in the three dimensions (P > 0.05). However, on the attitude dimension, pregnant women had scores of 4.16 ± 1.13 for item A1, 4.41 ± 0.78 for A2, and 2.75 ± 1.05 for A6, and lying-in women had scores of 3.75 ± 1.36, 4.22 ± 0.98 and 2.94 ± 1.09 for items A1, A2, and A6, respectively, with statistical differences in the scores of the three subscales (p < 0.001; 0.014; 0.038) The remaining detailed scores are shown in Table 2. In terms of knowledge dimension, 363 (61.11%) participants were correct that PPD is a common puerperal psychiatric syndrome that occurs within four weeks, 475 (79.97%) participants were correct that the occurrence of PPD is related to genetic, neuroendocrine disorders and psychosocial factors, 522 (87.88%) participants believed that PPD needs to be treated, and 417 (70.20%) participants were correct that medication should be avoided during breastfeeding, and overall, the majority of participants had a relatively correct understanding of PPD (Table 3). For Supplementary Table 1, the percentages of each sub-item score in the attitude dimension; for Supplementary Table 2, the percentages of each item score in the practice dimension.

Correlation analysis between the scores of the three different dimensions

By analyzing the two-by-two Pearson coefficients between the total scores of the three dimensions, the results showed that the Pearson coefficient between the practice score and attitude score was 0.162 (p < 0.001), the Pearson coefficient between practice score and knowledge score was 0.318 (p < 0.001), the Pearson coefficient between attitude score and knowledge score was 0.165 (p < 0.001), and all dimensions were positively correlated with each other (Table 4).

Factors associated with the practice scores

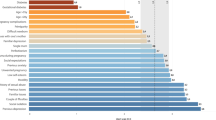

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that knowledge dimension scores, attitude dimension scores, age, education, work status, and current stage were the factors that influenced the practice dimension scores. When incorporating these factors into a multivariate logistic regression model, the results showed that knowledge scores (OR = 1.235, 95%CI: 1.128–1.353, P < 0.001 per 1 point), attitude scores (OR = 1.052, 95%CI: 1.005–1.102, P = 0.030 per 1 point), work status‘s others (OR = 0.431, 95%CI: 0.193–0.961, P = 0.040 vs. employed) and Current stage‘s postpartum period (OR = 1.509, 95%CI: 1.043–2.182, P = 0.029 vs. pregnancy period) were significantly associated with a higher practice score (Table 5).

Discussion

This preliminary cross-sectional study explores pregnant and lying-in women’s perceptions of PPD. We surveyed participants in three dimensions by creating a KAP questionnaire. The study results showed that maternal scores in the three dimensions differed across states, pregnant and maternal women had good knowledge of PPD in more than half of the participants, and that practice dimension scores correlated with knowledge and attitude scores. However, disregard for PPD remained prevalent among a minority of participants. Therefore, the KAP survey allows for a preliminary understanding of the different dimensions of PPD in the maternal population. Based on the results, education and coping measures for PPD can be developed and implemented to address these biases and negative stereotypes associated with PPD.

Studies on the link between KAP and PPD are rare, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, which may have had a direct psychological and social impact on pregnant women and women who have just given birth due to the relative restriction of social activities. In this study, we found statistically significant differences in their scores on the three dimensions of KAP across age groups, education, and work status. This is more consistent with the findings of previous studies. Silva et al. [17] found statistical differences in anxiety-depression scores by maternal age through a questionnaire survey of pregnant women. At the same time, PPD was associated with age and a high rate of PPD among lying-in women, which is associated with maternal anxiety and should further enhance mental health during pregnancy and puerperium. A meta-analysis of a Chinese study by Nisar et al. [18] found that the prevalence of perinatal depression showed an increasing trend in the last decade. At the same time, a higher educational level was a protective factor. Our study showed that as educational background increased, higher education was associated with higher KAP scores. Using a sample analysis of 15,000 mothers in a nationwide French cohort, Nakamura et al. [19] found occupational rank. Employment and higher socioeconomic status made possible by education reduced the occurrence of PPD, with higher scores for those who were employed than for those who were not employed and those who worked part-time in the three dimensions. Overall, we should pay further attention to pregnant women and lying-in women with low scores on the three dimensions.

Although our results showed no statistically significant differences in the scores of women during pregnancy and lying-in on the three dimensions, there were differences in the scores obtained by women at different periods on some subitems. Analysis of the subitems with differences showed that women during pregnancy took PPD more seriously in their mindset and actions and were more willing to be proactive in being screened for PPD. A woman in labor is likely to worry about how to care for her child, which can cause them anxiety. Also, the hormonal changes and frequent mood swings from pregnant women to mothers may affect their perception of PPD. Pięta et al. [20] argue that special attention should be paid to women who experience negative mental states during pregnancy. They argue that mood changes during pregnancy, labor, and lying in are often extreme and can change significantly in short periods. For their part, researchers such as Andrzej [21] suggest practical actions in the field of public health, which would raise awareness among young women and pregnant women and make them aware of the importance of physical activity for their pregnancy and childbirth process. We also believe we should provide psychological support to pregnant women to enhance their awareness of PPD.

Our results show a positive correlation between maternal scores on the three dimensions, with the three dimensions influencing each other. Previous studies generally agree that there is a correlation between knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Alsabi [22] surveyed social support networks during the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia, and they found that public perceptions of PPD were correlated with their knowledge and attitudes. Highet et al. [23] investigated three aspects of perinatal depression awareness, attitudes, and knowledge among Australians, and they concluded that people without mental health training had lower awareness and attitudes towards the etiology of PPD, and when awareness increased, the attitudes towards PPD also changed. Jones et al. [24] conducted a national survey of midwives and found that when midwives are professionally educated, and their knowledge is improved, it also leads to better cognitive and practical skills in assessing and caring for women with PPD. Likewise, Elshatarat [25] believes that educating healthcare professionals and improving their understanding of PPD will improve their knowledge, practice, and self-confidence. We also believe daily information should be provided to pregnant women to understand PPD and prevent it by increasing knowledge and positive attitudes towards PPD.

For maternal practice aspects, we concluded through multivariate logistic regression analysis that the knowledge and attitude dimensions influence practice. At the same time, the postpartum period will have a higher practice score than the pregnancy period (OR = 1.509 [1.043–2.182]). It is essential for maternity to put into practice both psychological and behavioral aspects of the intervention. Earls et al. [26] argued that payment should be advocated for increased training in the screening and treatment of PPD, with significant support for the mother-infant relationship, and for the identification of perinatal depression to be incorporated into pediatric practice. A randomized controlled trial by Meng et al. [27] concluded that a circulatory care intervention positively affected postpartum anxiety and depression and significantly reduced the incidence of PPD. We believe that pregnant and lying-in women should be motivated to act and seek interventions to prevent PPD. A meta-analysis by Zhou et al. [28] also concluded that pregnant women should actively use portable electronic devices to address depressive symptoms in postpartum women, increase knowledge of PPD through electronic devices to change their attitudes and use mHealth interventions to complement routine clinical care for PPD. Therefore, maternal practice is crucial to reducing the incidence of PPD by providing maternal guidance through knowledge and attitudes so that they can be more proactive in seeking professional help. It may be that hormonal changes and the impact of the newborn and the family on the mother make postpartum women more aggressive in seeking help. However, better results are obtained with behavioral interventions early in pregnancy.

This study has some limitations; firstly, this sample is from a single center. At the same time, there is also an insufficient sample size; future multi-center studies are needed to expand the sample size. Secondly, despite the high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, the KAP survey may need to be validated by more institutions as it is artificially designed.

Conclusions and recommendations

This KAP study revealed that pregnant and lying-in women had relatively good knowledge and positive attitudes toward PPD. Better knowledge and positive attitudes can also improve practice toward PPD. Therefore, it is essential to develop appropriate policies to educate mothers about PPD and improve their attitudes and practices toward PPD. Such improvements could have public health implications, considering that PPD is associated with serious morbidity.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, Attitude and Practice

- PPD:

-

Postpartum depression

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

References

Hodgkinson EL, Smith DM, Wittkowski A. Women’s experiences of their pregnancy and postpartum body image: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:330.

Melzer K, Schutz Y, Boulvain M, Kayser B. Physical activity and pregnancy: cardiovascular adaptations, recommendations and pregnancy outcomes. Sports Med. 2010;40(6):493–507.

O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379–407.

Payne JL, Maguire J. Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in postpartum depression. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;52:165–80.

Liu X, Wang S, Wang G. Prevalence and risk factors of Postpartum Depression in women: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(19–20):2665–77.

Xie RH, Yang J, Liao S, Xie H, Walker M, Wen SW. Prenatal family support, postnatal family support and postpartum depression. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(4):340–5.

Poreddi V, Thomas B, Paulose B, Jose B, Daniel BM, Somagattu SNR, B VK. Knowledge and attitudes of family members towards postpartum depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34(6):492–6.

Lin C, Chen B, Yang Y, Li Q, Wang Q, Wang M, Guo S, Tao S. Association between depressive symptoms in the postpartum period and COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:247–53.

Sharma H. How short or long should be a questionnaire for any research? Researchers dilemma in deciding the appropriate questionnaire length. Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16(1):65–8.

Temtanakitpaisan T, Bunyavejchevin S, Buppasiri P, Chongsomchai C. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) survey towards pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) among pregnant women. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:295–9.

Aiga H, Nguyen VD, Nguyen CD, Nguyen TT, Nguyen LT. Knowledge, attitude and practices: assessing maternal and child health care handbook intervention in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:129.

Dominiak M, Antosik-Wojcinska AZ, Baron M, Mierzejewski P, Swiecicki L. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum depression. Ginekol Pol. 2021;92(2):153–64.

Kroska EB, Stowe ZN. Postpartum Depression: identification and treatment in the clinic setting. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2020;47(3):409–19.

Van Niel MS, Payne JL. Perinatal depression: a review. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(5):273–7.

Lee F, Suryohusodo AA: Knowledge, attitude, and practice assessment toward COVID-19 among communities in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2022;10:957630.

Thirunavukkarasu A, Al-Hazmi AH, Dar UF, Alruwaili AM, Alsharari SD, Alazmi FA, Alruwaili SF, Alarjan AM. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards bio-medical waste management among healthcare workers: a northern Saudi study. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13773.

Silva RS, Junior RA, Sampaio VS, Rodrigues KO, Fronza M. Postpartum depression: a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34(17):2801–6.

Nisar A, Yin J, Waqas A, Bai X, Wang D, Rahman A, Li X. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:1022–37.

Nakamura A, El-Khoury Lesueur F, Sutter-Dallay AL, Franck J, Thierry X, Melchior M, van der Waerden J. The role of prenatal social support in social inequalities with regard to maternal postpartum depression according to migrant status. J Affect Disord. 2020;272:465–73.

Pięta B, Jurczyk MU, Wszołek K, Opala T. Emotional changes occurring in women in pregnancy, parturition and lying-in period according to factors exerting an effect on a woman during the peripartum period. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2014;21(3):661–5.

Wojtyła A, Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Biliński P, Paprzycki P. Physical activity among women at reproductive age and during pregnancy (youth behavioural Polish survey - YBPS and pregnancy-related Assessment Monitoring Survay - PrAMS) - epidemiological population studies in Poland during the period 2010–2011. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18(2):365–74.

Alsabi RNS, Zaimi AF, Sivalingam T, Ishak NN, Alimuddin AS, Dasrilsyah RA, Basri NI, Jamil AAM. Improving knowledge, attitudes and beliefs: a cross-sectional study of postpartum depression awareness among social support networks during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):221.

Highet NJ, Gemmill AW, Milgrom J. Depression in the perinatal period: awareness, attitudes and knowledge in the Australian population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(3):223–31.

Jones CJ, Creedy DK, Gamble JA. Australian midwives’ knowledge of antenatal and postpartum depression: a national survey. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(4):353–61.

Elshatarat RA, Yacoub MI, Saleh ZT, Ebeid IA, Abu Raddaha AH, Al-Za’areer MS, Maabreh RS. Perinatal nurses’ and midwives’ knowledge about Assessment and Management of Postpartum Depression. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2018;56(12):36–46.

Earls MF, Yogman MW, Mattson G, Rafferty J. Incorporating Recognition and Management of Perinatal Depression into Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics 2019;14(1).

Meng J, Du J, Diao X, Zou Y. Effects of an evidence-based nursing intervention on prevention of anxiety and depression in the postpartum period. Stress Health. 2022;38(3):435–42.

Zhou C, Hu H, Wang C, Zhu Z, Feng G, Xue J, Yang Z. The effectiveness of mHealth interventions on postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28(2):83–95.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K W, R L, QQ L, ZZ L and N L carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. J W, YD Y, K W performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University Hospital (approval no. LW-37), and written informed consent was obtained from the participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table 1

. The score distribution of “attitude” dimension

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Table 2

. The score distribution of “practice” dimension

Supplementary Material 3: Supplementary Figure S1

. Results of the confirmatory factor analysis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Li, R., Li, Q. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward postpartum depression among the pregnant and lying-in women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 762 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06081-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06081-8