Abstract

Background

Ethiopia has been striving to promote institutional delivery through community wide programs. However, home is still the preferred place of delivery for most women encouraged by the community`s perception that delivery is a normal process and home is the ideal environment. The proportion of women using institutional delivery service is below the expected level. Therefore, we examined the impact of perception on institutional delivery service use by using the health belief model.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 1,394 women who gave birth during the past 1 year from September to December 2019. A multistage sampling technique was used to select the study participants. Data were collected by using health belief model constructs, and structured and pretested questionnaire. Binary logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with the outcome variable at 95% confidence level.

Results

Institutional delivery service was used by 58.17% (95% CI: 55.57- 60.77%) of women. The study showed that high perceived susceptibility (AOR = 1.87; 95% CI 1.19–2.92), high cues to action (AOR = 1.57; 95% CI: 1.04–2.36), husbands with primary school education (AOR = 1.43; 95% CI 1.06–1.94), multiparty(5 or more) (AOR = 2.96; 95% CI 1.85–4.72), discussion on institutional delivery at home (AOR = 4.25; 95% CI 2.85–6.35), no close follow-up by health workers (AOR = 0.59;95% CI 0.39–0.88), regular antenatal care follow-up (AOR = 1.77;95% CI 1.23,2.58), health professionals lack of respect to clients (AOR = 2.32; 95% CI 1.45–3.79), and lack of health workers (AOR = 0.43;95% CI 0.29–0.61) were significantly associated with the utilization health behavior of institutional delivery service.

Conclusion

The prevalence of institutional delivery in the study area was low. The current study revealed that among the health belief model construct perceived susceptibility and cues to action were significantly associated with the utilization behavior of institutional delivery service. On top of that strong follow-up of the community and home based discussion was a significant factor for the utilization behavior of institutional delivery service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, the major causes of maternal deaths are due to direct obstetric complications including obstructed labor [1]. In 2014, births assisted by skilled health personnel increased to 71% from 59% to 1990 [2]. A care that is given for women during pregnancy, delivery and after delivery is vital for the well-being of both the mother and the new born [3].

Encouraging skilled delivery has a significant effect in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality; which has been practiced for more than two decades in Latin America and showed a visible progress. Pregnancy-related complications were high in Asia and Africa; and leading the world at large [4]. Maternal mortality in remote-rural communities who have poor access to health care remains high compared to urban setting [5]. For the improvement of maternal and new born child care in low and middle income countries, ensuring and promoting access to the ante-natal care and skilled birth attendant during delivery is a key strategy [6].

In Ethiopia, in spite of all the efforts made to improve the outcomes of maternal health, the number of women who get skilled birth attendant is still very low [7]. Direct obstetric complications are the major causes of maternal death in Ethiopia including prolonged/obstructed labor [8]. According to the 2015 united Nation (UN) and the 2019 Ethiopian Ministry of Health estimate, there is a significant progress on reducing the maternal mortality in Ethiopia, there is a significant progress on reducing the maternal mortality in Ethiopia [9]. The utilization of maternal health service particularly skilled birth attendant at health facility in Ethiopia increased substantially after 2005; from 6% in the 2000 and 2005 Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) to 10% in 2011 EDHS, 26% in 2016 EDHS [10] and reached 50% in 2019 [11], but still it is low as compared to the Health Sector Transformation Plan of Ethiopia (HSTP-II) [12].

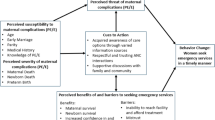

Different studies conducted on institutional delivery service utilization identified individual level factors like perception, attitude and beliefs affecting health facility delivery service utilization [13,14,15,16,17,18].The determinants of individual’s health related behaviors and the way of motivating favorable changes can easily facilitated by behavioral theories and models, including the health belief model (HBM). The HBM was developed initially in the 1950s by social psychologists in the U.S. Public Health Service to explain the widespread failure of people to participate in programs to prevent and detect disease [19,20,21,22] Later, the model was extended to study people’s responses to symptoms [23] and their behaviors in response to a diagnosed illness, particularly adherence to medical regimens [24] and modified by Rostenstock in 1990 [25] as one of the value expectancy theory, develop preventive and utilization health behavior theories.

The HBM assumes that the likelihood of behavior (delivery at health facility) is predicted by (1) the individual’s perceived severity of giving birth out of health facility, (2) the individual’s perceived susceptibility of birth complications due to giving birth out of health facility, (3) the perceived net benefit of institutional delivery (if the perceived benefit outweighs the perceived barrier), (4) perceived barrier to institutional delivery, (5) the individual’s self-efficacy for institutional delivery service utilization, and (6) exposure to cues-to-action (information that motivates for institutional delivery service use) [26, 27].

Many of the previous study conducted in Ethiopia on institutional delivery service use and factors associated with it did not use the HBM constructs to understand the relationship between perceptions and institutional delivery service use with the help of skilled health personnel. Therefore, the current study aimed to determine the magnitude of institutional delivery service use and its associated factors in rural Central Gondar Zone, North West Ethiopia using the HBM.

Methods

Study design, period and setting

A community based cross sectional study was conducted among women in 15 rural kebele (the smallest administrative units of Ethiopia) of Central Gondar zone, Northwest Ethiopia, from September to December, 2019. Central Gondar zone is found in Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) and its capital city, Gondar is located 727Kms away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. According to the 2007 census, the Zone has a population of 2,288,442 inhabitants of whom 462,952 were women of reproductive age. According to the 2019 Central Gondar zone health department report, there were 14 districts (2 urban and 12 rural), 75 health centers and 9 hospitals in the zone [28].

Sample size

We calculated the sample size using single population proportion formula;

-

n = z (a/2)2p (1-p)/d2

-

n = Sample size

-

Za/2= 1.96 standard score corresponding to 95% CI

-

d = 0.03 margin of error

-

p = 0.271 (Proportion of institutional delivery service utilization in Amhara region) [10].

-

d = 0.05

-

n = z (a/2)2p (1-p)/d2

-

n = (1.96)20.271(1-0.271)/ (0.03)2= 845

-

n = 845, since there is design effect we multiply by 1.5 then it will be 1,267 with 10% non-response rate, it will give 1,394.

Therefore the maximum sample size was 1,394 women who gave birth in the last 12 months.

Sampling procedures

We employed a multistage sampling technique to select the study participants. By taking 20–30% as a rule of thumb for representativeness, in the first stage among 12 rural districts of the zone we selected randomly two sample rural districts (Dembiya and Wogera) which are composed of 51 kebeles (24 kebele from Dembiya and 27 kebele from Wogera). In the second stage, among the 51 kebeles 15 kebeles were selected with a simple random sampling technique from the two selected districts proportionally. Within the selected kebele, households having the eligible study participants (women who gave birth within the past 1 year) were identified by using the maternal and child registration book of HEWs. Within the registration book, women who gave birth within the past 1 year in each kebele were identified before the survey; and we used this as a sampling frame to select the study participants. The HEWs are health cadres who are high school graduates and received 1-year training to deliver packages of preventive and health promotion services and few basic curative services.

Then, systematic random sampling was used within kth (5th ) cases from each kebele to get representative participants until we addressed the required samples. Proportional sampling was done based on the number of women who gave birth in the last year living in the selected kebele using last year’s pregnant women’s registration book as sampling frame in the health post. In connection to this, we selected randomly the first study participant from the list.

Data collection tool, procedure, and quality control

Appropriate questions of the health belief model were designed by reviewing theoretical aspects of the model, articles, and accessible guides for each of the HBM constructs using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (score range of 1–5) [25, 26, 29,30,31,32]. In addition, a structured questionnaire which was developed by reviewing literatures [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] was developed for the socio-demographic and institutional delivery service. The questionnaire was piloted (field tested) to make the questionnaire clear. It was initially prepared in English and translated to the local language Amharic and back translated to English by language experts to see the consistency.

Based on the six HBM construct 37 questions were included for the health belief model construct, i.e. five questions of “perceived susceptibility” with a score range of 5–25, seven questions of “perceived severity” with a score range of 7–35, six questions of “perceived benefits” with score range of 6–30, eight questions of “perceived barriers” with score range of 8–40, three questions of “self-efficacy” with a score range of 3–15, and eight questions of “cues to action” with a score range of 8–40).

The entire questionnaire was pretested on 70 women (5% of the entire sample size) in the rural communities of West Gojjam zone, Bahir Dar Zuria districts which has similar context with the study area.

The main survey data were collected by ten nurses and supervised by three public health officers. Two days training was given for the data collectors and supervisors about the objectives and data collection process by the principal investigator. The data were checked for accuracy and consistency daily.

To minimize potential bias, we have conducted different strategies at the design, data collection and analysis stage. The sample size was sufficiently large to estimate the prevalence with adequate precision. The study population was clearly stated at the design stage, trying to achieving high response rate (≥ 80%) to prevent non-response bias, this was facilitated by using questionnaires that are not too long and don’t take too much time to complete. Field-testing / piloting of questionnaire was conducted in order to improve and refine it, necessary training was given for the data collectors and supervisors which helps to prevent information and interviewer bias. To avoid response bias for the likert types of questions we have carefully designing our survey questionnaire by involving different experts for ensuring the content validity, we have provided a simple, exhaustive set of answer options, we also use precise and simple language, it was structured appropriately, we have trying to personalize the survey by keeping our target audience in mind, and continuously track the metrics to be measured. To avoid confounding bias, we have used multivariable analysis during the analysis stage.

Study variables

The outcome variable of the study was institutional delivery service use which was defined or coded as “Yes” if women reported that they gave their most recent birth (within the last 1 year) at health institution, and “No” if otherwise.

The independent variables of the study includes basic socio-demographic information (age, marital status, educational status of mothers, educational status of the husband, family size and parity or number of child birth), health message delivery system and supportive supervision ( home based discussion on institutional delivery service use, information delivery system, follow-up by health workers, history of health facility on institutional delivery service given and respectful health care delivery practice), maternal health service use behavior and characteristics of the health facility (ANC follow-up, time and cost invested for the service, place of birth, status of child birth, location of health facility and health workers) and the HBM constructs (perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy and cues to action).

Data processing and analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness, consistency, and missing values; coded and entered, using Epi Data version 3.1 and cleaned and analyzed using STATA software version14.1.

Using descriptive methods, the data was summarized, prevalence of institutional delivery service use was determined and odds ratios (OR) were determined using logistic regression. The data obtained from individuals in each household were pooled to create a single large data set then the studies used the number of individuals institutional delivery service use analyzed as the statistical n value, which is we assume the data gathered at each kebele to be an independent measurement so that we can use simple logistic regression by ignoring clustering [41].

The HBM constructs originally comprised of an item with a five 5-point scale of question responses (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) were computed in to another scale response category by collapsing responses for 1 and 2 into a disagree category and 4 and 5 into an agree category, yielding a 3-point scale: 1 = disagree, 2 = neutral, and 3 = agree. Then, dichotomized scale responses were generated by collapsing responses for 1 through 3 from the original scale to 0 = disagree and 4 and 5 to 1 = agree. The rationale of dichotomization between 3 and 4 from the original scale was that the preface of questions regards people who answered higher than or equal to 4 as those who agreed with the statement in an item [42]. Then, those respondents who scored above 60% of the total construct score were considered as high and the remaining were low. The cutoff point for this categorization was calculated using the demarcation threshold formula: cutoff point = (over all highest score-over all lowest score)/2+ total lowest score. In addition, the standardized mean of each construct was calculated by dividing the mean score by the number of questions in order to make the mean importance of each dimension of HBM constructs comparable.

The effect of different variables including the HBM constructs on institutional delivery service use was explored using crude and adjusted odds ratios. After checking the correlation of independent variables, significance was determined using crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence level. To determine the association between the different predictor variables with the dependent variable, first bi-variable analysis between each independent variable and outcome variable was investigated using a binary logistic regression model and then all variables having p-value < 0.2 in the bi-variable analysis were considered as a criterion for variable selection for inclusion into a multivariable model. So, all variables with a p-value of < 0.2 in the bi-variable were used for multi-variable logistic regression.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) was calculated to show the presence and strength of associations. A variable with p-value of less than 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression model was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the respondents

In this study a total of 1,389 women who gave birth in the last 12 months were interviewed with 99.6% response rate. The mean age of the respondents was 30 years old (SD = ± 0.15). In this study, 1,105 (79.55%) of the respondents could not read and write. Regarding their parity status, 644 (46.36%) had 3–4 child birth. Meanwhile 1,254 (90.2%) of the respondents were married (Table 1).

Health message delivery and supportive-supervision system

Respondents were asked about the health message delivery and supportive supervision system undertaken in the local context. The study showed that more than two-third 969 (69.76%) of the respondents have a home based discussion on institutional delivery. With respect to health facility history, 833 (59.97%) of the respondents were reported that the health facility in child birth had bad history (Table 2).

Institutional delivery service use

The study indicated that two-third 943 (67.89%) of the respondents had regular ANC follow-up in their last pregnancy, and more than half 808 (58.17%) of the women delivered their last child at health institution. However, 543(39.09%) of the respondents reported that the service given at the health facilities were time-consuming and costly (Table 3).

Health Belief Model (HBM) constructs

The standardized mean score of each dimension of HBM constructs was calculated by dividing the mean score by the number of questions. The “self-efficacy” had the highest mean (3.82), followed by “cues to action” (3.75), “perceived benefits” (3.73), and “perceived susceptibility” (3.10). Whereas the lowest mean belonged to “perceived barriers” (2.66) (Table 4).

The study showed that 821 (59.11%) of the study participants had high perceived benefit of institutional delivery, of which 589 (71.7%) gave birth at health facility. Near to three-fourth 1,013 (72.93%) of study participants had high cues to action for institutional delivery service use, of which 672 (66.3%) gave birth at health facility. Regarding the perceived susceptibility, 710 (51.12%) of the participant had low perceived susceptibility of birth complications for delivery out of health facility, of which only 312 (43.9%) gave birth at health facility for their last birth. Similarly, 716 (51.55%) of the study participants had low perceived severity of bringing delivery out of health facility, of which only 321 (44.8%) gave birth at health facility for their last birth (Table 5).

Health belief model constructs and other factors associated with institutional delivery service use

Using bivariate analysis the relationship between institutional delivery service use and predictor variables was first assessed. In the bivariate analysis, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefit, perceived barrier, self-efficacy, cues to action, age of respondents, educational status of husband, parity, home based discussion on institutional delivery, no close follow-up by health workers, regular ANC follow-up, location of health facility, status of birth, service at health facility is time consuming and costly, poor information delivery system, bad history of health facility in child birth, lack of respectful health care practice and lack of health workers were statistically significantly associated with institutional delivery service use (p < 0.05).

The independent effect of each predictor variable was examined by performing a multivariate logistic regression, and the result is presented in Table 6 below. Accordingly, among the health belief model constructs perceived susceptibility and cues to action were significantly associated with institutional delivery service use; Women with high perceived susceptibility of birth complications were near to two folds (AOR = 1.87; 95% CI: 1.19, 2.92) more likely to give birth at health facility compared to women with low perceived susceptibility of birth complications. Similarly, women with high cues to action for institutional delivery service use were more than one -and half folds more likely to give birth at a health facility (AOR = 1.57;95% CI: 1.04,2.36) than those women with low cues to action for institutional delivery service use.

Women who had discussion on institutional delivery at home were 4.25 times more likely to give birth at health facility as compared to their counterparts (AOR = 4.25; 95% CI 2.85,6.35).Women who attended regular ANC visit for their last pregnancy were one –and more than half (AOR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.23, 2.58) folds to give birth at health facility. The odds of institutional delivery were more than eight-and half folds (AOR = 8.51;95% CI 5.89, 12.28) among women who had a family size of less than five as compared to those women who had a family size greater than or equal to five. Husband educational status was significantly associated with institutional delivery service use; those with primary educational status were one –and near to half fold to give birth at health facility (AOR = 1.43 ;95% CI 1.06, 1.94) than those educational status was unable to read and write.

The odds of giving birth at health facility was more than two folds (AOR = 2.32; 95% CI 1.45, 3.71) among women who reported that there was respectful health care delivery as compared to their counter parts.

However, the odds of giving birth at health facility was 41% (AOR = 0.59; 95% CI: 0.39, 0.88) less likely among women who reported that there was no close follow-up by health workers compared to women who reported that there was close follow-up by health workers. Similarly, women who reported that there was lack of health workers were 67% less likely to give birth at health facility compared to women who reported that there was no lack of health workers (Table 6).

Discussion

Health belief model is one of the most extensively used and robust individual level models to measure behaviors in high income settings. We used this model to assess institutional delivery service use in a rural setting and examine which constructs of the model best predict such a behavior.

The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of health has included and is implementing the health policy that provides free maternal health care services for all women during pregnancy, labor and post natal period in the governmental health facilities. However, the use of institutional delivery service among women was over half in the study area, Central Gondar zone, North West Ethiopia, which is not satisfactory. Among the health belief model constructs perceived susceptibility and cues to action were predictor variables for the use of institutional delivery. Other factors that were significantly associated with the use of institutional delivery service were educational status of husband, parity/number of child birth, home based discussion on institutional delivery, no close follow-up by health workers, regular ANC follow-up, health professionals lack of respect to clients and lack of health workers.

Utilization behavior of individual is driven by their perception to take over the action and the expectation of people to carry out their perception when the opportunity arises. Individual will be involved in the health behavior if and only if their perceived threat outweighs the barrier [26]. In this study, the use of institutional delivery was low as compared to other studies conducted in other parts of Ethiopia: Mana district [43], Pawe district [44], BenchMaji [45] and Boset [46]. This might be due to differences in socio-cultural context[47] the current study area was two different districts, low level of community readiness for the promotion of institutional delivery [48], poor awareness creation on the consequences and complications of birth outcome at home [13] and lack of the integration of conscious raising program on institutional delivery service use with the cultural and social system in the community [49, 50].

Women’s perceived susceptibility to birth-related complications was significantly associated with utilization of health facility for birth. Poor awareness of community regarding the possible birth complications had a great impact on the health facility use during delivery service by the community at large [13, 16, 51]. The level of perception of women about the risks of giving birth at home could be determined based on their previous experiences of complications of home delivery by themselves, family, neighbors and the community at large; which in-turn determines the subsequent delivery places [31, 52,53,54]. Consequently, women may prefer giving birth at health facility based on their high perceived susceptibility to birth complications at home [55,56,57]. This implies that intensifying women’s perception regarding their susceptibility for birth complications at home over health facility could inspire them to visit health facility for every birth.

In the current study, cues to action for using health facility during child birth were positively associated with utilization health behavior for institutional delivery service.

Earlier studies showed that cues to action such as health learning materials like leaflet, poster, radio, newspaper; health workers respectful health care delivery, recommendations from religious fathers and kebele leaders [32, 58, 59], are important motivational factors to be involved in the desired behavior. Cues to action are motivational factors making women to be aware of the benefit of institutional delivery over home delivery and being alert whenever they think of giving childbirth [60,61,62].This implies that provision of different reminders by using locally available health learning material in order to address the community at large via considering the accessibility and availability of health learning material for the local context shall to be considered.

In this study, parity and home based discussion on institutional delivery service use were found to be significantly associated with health facility delivery care service use among study participants. This finding was in line with a study in Nepal [63] and in different areas of Ethiopia [64, 65]. Having home based discussion on different health issues has been also assessed in other studies [3] and indicates that it was a significant factor for the service use. Home based discussion on institutional delivery service use could enhance the uptake of the maternal health service in the large communities [66]. This implies that encouraging the community with a strong follow-up at a house hold level and making them to have a detailed discussion and taking appropriate solutions on barriers that hinder health care service uptake is a vital; and crucial strategy that everyone could takeover.

The study showed that, health professional’s lack of respect to clients and lack of health workers at health facility were significantly associated with the use of health facility for child birth among women with less than 1 year children in the study area. The practice of respectful health care delivery has high probability of positive impact on the service utilizer to visit again and build up a positive image by the large community [67, 68]. A health facility with low number of health care providers could have a negative impact on the service utilization; limited number of health care provender might not be serve the community as per the professional standard due to tiredness and fatigue, as a result they might not treat the clients respectfully [69,70,71]. This implies that the government, at each level of the health system tier, shall deploy a minimum number of health care providers as per the standards.

The odds of institutional delivery were higher among women who had a regular ANC follow-up in the current study area. This result was in-line with studies conducted in Mandura district, Pawi district, Hosanna, and rural area of Hadya zone in Ethiopia [72,73,74,75]. ANC follow-up provides opportunity for women to receive information about the benefits of institutional delivery.

Educational status of husband was found to be important determinants of institutional delivery service use. Women who had husbands with a primary school level education had a significant role in determining place of delivery. This finding was in agreement with other studies in Bangladesh, Sub-Saharan Africa, Eritrea and Nepal [76,77,78,79,80]. This might be due to the accessibility of the information and health education; service knowledge, and wise resource utilization that could be improved through educational level; and the preference of individuals for delivery at health facility would be improved easily by changing people’s attitude towards their preference of delivery [73, 81, 82]. This implies that strengthening adult education at the local level is a necessary and mandatory step for the improvement of institutional delivery service use.

The present study revealed that women who reported that there was no strong close follow-up by health workers were less likely to give birth in health facility compared to women who reported there was close follow-up by health workers. This finding is in line with an interventional study conducted in Melawi and Ethiopia in different area [83,84,85].The reason might be community who is closely advised and supervised by the health workers are often involved in, or consulted about, services, and service use; which makes them to be active utilizer of the services. This implies that there should be an established close follow-up system within the health facility and shall to be incorporated in the health workers performance appraisal systems.

Strengths and limitations

Addressing the perception of rural women on the utilization health behavior of institutional delivery service using the constructs of health belief model could be the strengths of this study. The possible limitations of this study might be related to the focus of the health belief model i.e. the model emphasizes on individual level factors. Hence, determinants beyond the individual level factors like the social and structural factors may not have been addressed.

Conclusion

The result of the current study indicated that perceived susceptibility, cues to action, parity, home based discussion on institutional delivery, close follow-up by health workers, respectful health care delivery practice, lack of health workers, husband educational status and regular ANC follow-up were some of the predictive variable which had the highest power in predicting the utilization behaviors of institutional delivery. Therefore, it is necessary to design an intervention to increase awareness in women and the community at large to promote utilization health behaviors; this can be addressed by strengthening peer-health education on the possible complications of birth at home and awareness creation activities using different social systems are recommended. Designing and establishing a platform for the follow-up of the community and a system of home based discussion enables the community to adopt the desirable behavior i.e. utilization behavior. Increasing the motivational factors i.e. cues to action and giving more attention for respectful health care delivery practice might also promote utilization of institutional delivery service.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available at University of Gondar, College of medicine and Health Science, Institute of Public Health in hard and soft copy repository [www.UoG.edu.et]. In addition the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the principal investigators (Adane Nigusie- E-mail adane_n@yahoo.com).

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Ante Natal Care

- ANRS:

-

Amhara National Regional State

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratios

- BSC:

-

Bachelor of Science

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- COR:

-

Crude Odd Ratio

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey

- HBM:

-

Health Belief Model

- HEW:

-

Health Extension Workers

- HSTP:

-

Health Sector Transformation Plan

- HW:

-

Health Workers

- UN:

-

United Nation

References

Zelalem Ayele D, Belayihun B, Teji K, Admassu Ayana D. Factors affecting utilization of maternal health Care Services in Kombolcha District, eastern Hararghe zone, Oromia regional state, eastern Ethiopia. Int Scholarly Res Notices. 2014;2014:1–8.

Way C. The millennium development goals report 2015. UN; 2015.

Exavery A, Kanté AM, Njozi M, Tani K, Doctor HV, Hingora A, et al. Access to institutional delivery care and reasons for home delivery in three districts of Tanzania. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):1–11.

González-Santos SP. Cross-border reproductive healthcare. Taylor & Francis; 2020.

Kinney MV, Kerber KJ, Black RE, Cohen B, Nkrumah F, Coovadia H, et al. Sub-Saharan Africa’s mothers, newborns, and children: where and why do they die? PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000294.

Amouzou A, Ziqi M, Carvajal–Aguirre L, Quinley J. Skilled attendant at birth and newborn survival in Sub–Saharan Africa. J Global Health. 2017;7(2):1–11.

Fekadu M, Regassa N. Skilled delivery care service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of rural-urban differentials based on national demographic and health survey (DHS) data. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(4):974–84.

Arba MA, Darebo TD, Koyira MM. Institutional delivery service utilization among women from rural districts of Wolaita and Dawro zones, southern Ethiopia; a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151082.

World Healh Organization. Success factors for women’s and children’s health: Ethiopia. 2015.

TDP I. Health Survey (EDHS). 2016: Key Indicators Report, Central Statistical Agency Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The DHS Program ICF Rockville, Maryland. 2016.

Indicators K. Mini Demographic and Health Survey. 2019.

Health FDRoEMo. Health sector transformation plan. (2015/16–2019/20). Federal Ministry of Health Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2015.

Shifraw T, Berhane Y, Gulema H, Kendall T, Austin A. A qualitative study on factors that influence women’s choice of delivery in health facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–6.

Gebre M, Gebremariam A, Abebe TA. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in Duguna Fango District, Wolayta Zone, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137570.

King R, Jackson R, Dietsch E, Hailemariam A. Barriers and facilitators to accessing skilled birth attendants in Afar region, Ethiopia. Midwifery. 2015;31(5):540–6.

Wilunda C, Quaglio G, Putoto G, Lochoro P, Dall’Oglio G, Manenti F, et al. A qualitative study on barriers to utilisation of institutional delivery services in Moroto and Napak districts, Uganda: implications for programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):1–12.

Lakew S, Tachbele E, Gelibo T. Predictors of skilled assistance seeking behavior to pregnancy complications among women at southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional community based study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1–8.

Peca E, Sandberg J. Modeling the relationship between women’s perceptions and future intention to use institutional maternity care in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Reproductive health. 2018;15(1):1–17.

Steckler A, McLeroy KR, Holtzman D. Godfrey H. Hochbaum. (1916–1999): from social psychology to health behavior and health education. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1864.

Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):328–35.

Rosenstock IM. What research in motivation suggests for public health. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1960;50(3_Pt_1):295–302.

Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–473.

Kirscht JP. The health belief model and illness behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):387–408.

Becker MH. The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):409–19.

Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model: explaining health behavior through experiences. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 1990:39–63.

Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The health belief model as an explanatory framework in communication research: exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015;30(6):566–76.

Tarkang EE, Zotor FB. Application of the health belief model (HBM) in HIV prevention: A literature review. Cent Afr J Public Health. 2015;1(1):1–8.

Central Gondar Zone. Central Gondar zone health departement 2019 annual report. 2019.

Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 2008;4:45–65.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. Wiley; 2008.

Berhe R, Nigusie A. Perceptions of Home Delivery Risk and Associated Factors among Pregnant Mothers in North Achefer District, Amhara Region of Ethiopia: The Health Belief Model Perspective. Family Med Med Sci Res. 2019;8(2):1–10.

Henshaw EJ, Freedman-Doan CR. Conceptualizing mental health care utilization using the health belief model. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2009;16(4):420–39.

Teferra AS, Alemu FM, Woldeyohannes SM. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, North West of Ethiopia: A community-based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):74.

De Brouwere V, Richard F, Witter S. Access to maternal and perinatal health services: lessons from successful and less successful examples of improving access to safe delivery and care of the newborn. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(8):901–9.

Kifle D, et al. Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: a triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):6.

Hailemichael F, Woldie M, Tafese F,. Predictors of institutional delivery in Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia. African journal of primary health care & family medicine. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 5(1).

Asmamaw LND, Adugnaw B. Assessing the magnitude of institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Debre Berhan, Ethiopia. J Pregn Child Health. 2016;3(3).

Tadele NLT. Utilization of institutional delivery service and associated factors in Bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia: community based, cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):101.

Abeje GAM, Setegn T. Factors associated with Institutional delivery service utilization among mothers in Bahir Dar City administration, Amhara region: a community based cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):22.

Asseffa NABF, Ayodele A. Determinants of use of health facility for childbirth in rural Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):355.

Galbraith SDJ, Vissel B. A study of clustered data and approaches to its analysis. J Neurosci. 2010;30(32):10601–8.

Jeong H, Lee W. The level of collapse we are allowed: Comparison of different response scales in Safety Attitudes Questionnaire. Biom Biostat Int J. 2016;4(4):00100.

Yoseph M, Abebe SM, Mekonnen FA, Sisay M, Gonete KA. Institutional delivery services utilization and its determinant factors among women who gave birth in the past 24 months in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10.

Wonde TE, Legesse M, Ayana M, editors. Utilization of Institutional Delivery and Associated Factors among Mothers in Rural Community of Pawe District North West Ethiopia, 2018. 31st EPHA Annual Conference; 2020.

Tadele N, Lamaro T. Utilization of institutional delivery service and associated factors in Bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia: community based, cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–10.

Taye Shigute STaLT. Institutional Delivery Service Utilization and Associated Factors among Women of Child Bearing Age at Boset District, Oromia Regional State, Central Ethiopia. J Women’s Health Care. 2017;6(5).

Ababor S, Birhanu Z, Defar A, Amenu K, Dibaba A, Araraso D, et al. Socio-cultural Beliefs and Practices Influencing Institutional Delivery Service Utilization in Three Communities of Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2019;29(3).

Adane Nigusie TA, Yitayal M, Derseh L. Low level of community readiness prevails in rural northwest Ethiopia for the promotion of institutional delivery. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38(281).

Martin LT, Plough A, Carman KG, Leviton L, Bogdan O, Miller CE. Strengthening integration of health services and systems. Health Aff. 2016;35(11):1976–81.

Ejike CN. The Influence of Culture on the Use of Healthcare Services by Refugees in Southcentral Kentucky: A Mixed Study. 2017.

UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2015: estimates from WHO. and the United Nations Population Division: World Health Organization; 2015.

Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF. Maternal complications and women’s behavior in seeking care from skilled providers in North Gondar, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e60171.

Shiferaw BB, Modiba LM. Women’s perspectives on influencers to the utilisation of skilled delivery care: an explorative qualitative study in north West Ethiopia. Obstetr Gynecol Int. 2020;2020.

Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low-and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):1–17.

Mehretie Adinew Y, Abera Assefa N. Experience of facility based childbirth in rural Ethiopia: an exploratory study of women’s perspective. J Pregnancy. 2017;2017.

Atukunda EC, Mugyenyi GR, Obua C, Musiimenta A, Najjuma JN, Agaba E, et al. When Women Deliver at Home Without a Skilled Birth Attendant: A Qualitative Study on the Role of Health Care Systems in the Increasing Home Births Among Rural Women in Southwestern Uganda. Int J Women’s Health. 2020;12:423.

Kumbani L, Bjune G, Chirwa E, Odland J. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a qualitative study of women’s perceptions of perinatal care from rural Southern Malawi. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):1–12.

McNeill KB. Communication Cues to Action Prompting Central Appalachian Women to have a Mammogram. 2004.

Wheeler KL. Use of the health belief model to explain perceptions of zoonotic disease risk by animal owners. Colorado State University; 2011.

Burner ER, Menchine MD, Kubicek K, Robles M, Arora S. Perceptions of successful cues to action and opportunities to augment behavioral triggers in diabetes self-management: qualitative analysis of a mobile intervention for low-income Latinos with diabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(1):e25.

Orji R, Vassileva J, Mandryk R. Towards an effective health interventions design: an extension of the health belief model. Online J Public Health Informatics. 2012;4(3).

Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(4).

Karkee R, Lee AH, Khanal V. Need factors for utilisation of institutional delivery services in Nepal: an analysis from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3).

Tadese F, Ali A. Determinants of use of skilled birth attendance among mothers who gave birth in the past 12 months in Raya Alamata District, North East Ethiopia. Clin Mother Child Health. 2014;11:164.

Olgira L, Mengiste B, Reddy PS, Gebre A. Magnitude and associated factors for institutional delivery service, among women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Ayssaita district, North East Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Medico Res Chronicles. 2018;5(3):202–23.

Jinka SM, Wodajo LT, Agero G. Predictors of institutional delivery service utilization, among women of reproductive age group in Dima District, Agnua zone, Gambella, Ethiopia. Med Pract Reviews. 2018;9(2):8–18.

Bulto GA, Demissie DB, Tulu AS. Respectful maternity care during labor and childbirth and associated factors among women who gave birth at health institutions in the West Shewa zone, Oromia region, Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Bante A, Teji K, Seyoum B, Mersha A. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who delivered at Harar hospitals, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):86.

Siraj A, Teka W, Hebo H. Prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility based child birth and associated factors, Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Mengesha MB, Desta AG, Maeruf H, Hidru HD. Disrespect and Abuse during Childbirth in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020.

Organization WH. Prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during childbirth. 2014. 2018.

Mitikie KA, Wassie GT, Beyene MB. Institutional delivery services utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last year in Mandura district, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243466.

Eshete T, Legesse M, Ayana M. Utilization of institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers in rural community of Pawe District northwest Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6.

Anshebo D, Geda B, Mecha A, Liru A, Ahmed R. Utilization of institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers in Hosanna Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243350.

Delibo D, Damena M, Gobena T, Balcha B. Status of Home Delivery and Its Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth within the Last 12 Months in East Badawacho District, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020.

Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M. Factors associated with the utilization of institutional delivery services in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171573.

Adde KS, Dickson KS, Amu H. Prevalence and determinants of the place of delivery among reproductive age women in sub–Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244875.

Al Kibria GM, Ghosh S, Hossen S, Barsha RAA, Sharmeen A, Uddin SI. Factors affecting deliveries attended by skilled birth attendants in Bangladesh. Maternal Health Neonatology and Perinatology. 2017;3(1):1–9.

Kifle MM, Kesete HF, Gaim HT, Angosom GS, Araya MB. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):1–15.

Shahabuddin A, De Brouwere V, Adhikari R, Delamou A, Bardaj A, Delvaux T. Determinants of institutional delivery among young married women in Nepal: Evidence from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4).

Nigatu AM, Gelaye KA. Factors associated with the preference of institutional delivery after antenatal care attendance in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Mezmur M, Navaneetham K, Letamo G, Bariagaber H. Individual, household and contextual factors associated with skilled delivery care in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184688.

Kachimanga C, Dunbar EL, Watson S, Cundale K, Makungwa H, Wroe EB, et al. Increasing utilisation of perinatal services: estimating the impact of community health worker program in Neno, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Datiko DG, Bunte EM, Birrie GB, Kea AZ, Steege R, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Community participation and maternal health service utilization: lessons from the health extension programme in rural southern Ethiopia. J Global Health Reports. 2019;3.

Medhanyie A, Spigt M, Kifle Y, Schaay N, Sanders D, Blanco R, et al. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to forward our heartfelt gratitude to the University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Institute of Public Health for data collection financial support.

Finally we would like to acknowledge study participants, data collectors and super visors for their time and contribution of this work.

Funding

There is no received grant from any fund agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN conceived and designed the study, participated in the data collection, performed analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the paper and revised the manuscript. TA, MY and LD assisted with the design, approved the proposal, and revised drafts of the paper, prepared and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Gondar with a ref. No O/V/P/RCS/05/1048/2019 on a date of March 4 2019. Official letter that explains the objectives of the study was written to the respective Amhara public Health Institute. The Amhara public Health institute wrote a letter to zonal health department. The zonal health department was wrote a letter of support for each selected district health office. The selected district health office in turn wrote a letter of support for the study kebeles for cooperation. The objectives and the benefits of the study were explained for the study participants. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant. On top of that, for the participants who were illiterate, the researcher read the information sheet, checked if they understood, and asked them to fingerprint when they agreed to participate, and this was approved by the ethical committee. The full name of the ethical committee which approved the procedure of ethical issues was: Professor Feleke Moges (Chair-person), Mr. Nigusie Yigzaw (Secretary), Dr. Missaye Mulat (Member), Dr. Alemayehu Tekilu (Member), Dr. Bimrew Admasu (Member), and Mr. Abyot Endale (Member). The right of the participants to withdraw from the study whenever they wanted to do so was respected. The anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents were ensured. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not-applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nigusie, A., Azale, T., Yitayal, M. et al. The impact of perception on institutional delivery service utilization in Northwest Ethiopia: the health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 822 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05140-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05140-w