Abstract

Background

Controlling massive haemorrhage from morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) at caesarean section is a major surgical challenge to obstetricians. This study compares different intra-operative interventions to control haemorrhage from morbidly adherent placenta and its impact on maternal morbidity.

Methods

Retrospective analysis was done for baseline characteristics, intra-operative and postoperative complications of 125 patients with morbidly adherent placenta who had elective CS at 35–38 weeks gestation in the period from 01/2012 to 01/2017. The included patients were categorized into three groups according to intra-operative interventions they had for controlling bleeding; Group A (n = 42) had only balloon tamponade, Group B (n = 40) had balloon tamponade and bilateral uterine artery ligation, in Group C (n = 43) all cases were managed by bilateral uterine artery ligation and inverting the cervix into the uterine cavity and suturing the anterior and/or the posterior cervical lips into the anterior and/or posterior walls of the lower uterine segment using the cervix as a natural tamponade.

Results

There were no differences of baseline characteristics of patients in all groups. Group C had significantly better outcomes as compared with groups A and B; less total blood loss (Group C 2869.5 ml vs Group B 4580 ml, Group A 4812 ml, P < 0.001), less requirement of blood transfusion more than 4 units (Group C 4/43, Group B 10/40,Group A 12/42, P < 0.02), significant reduction in prolonged hospital stay over 10 days (Group C 2/43, Group B 9/40,Group A 14/42, P < 0.001) and lower risk of coagulopathy (Group C 4/43, B 8/40, A 9/42), visceral injuries (Group C 4/43 vs B 8/40, A 10/42,P < 0.01) and need for hysterectomy (Group C 4/43 vs B 11/40, A 13/42,P < 0.001).

Conclusion

A combination bilateral uterine artery ligation and using the cervix as a natural tamponade are very effective and simple methods in controlling bleeding resulting from separated placenta accreta.

Trial registration

The findings are part of the research project registered in ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02590484. Registered 28 October 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is one of the major causes of massive obstetric haemorrhage. It is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of pregnancy. The steady rise of caesarean section (CS) delivery rates in recent years is associated with increasing incidence of both placenta previa and placenta accreta [1].The incidence of placenta accreta in the presence of placenta Previa increases from 24% after one caesarean section to 67% after four or more caesarean sections [2].

The optimal management of placenta accreta spectrum remains controversial. Whilst hysterectomy or conservative management are recommended in case of confirmed MAP during caesarean section [3] Intraoperative bleeding may occur due to either partial separation of the placenta following a tentative attempt to confirm diagnosis clinically or in cases of unconfirmed partial accreta.

There is lack of consensus on the optimal uterine sparing surgical approach to reduce intraoperative bleeding if MAP is partially separated. Whilst electing for timely hysterectomy may be recommended and lifesaving [3] this may not be ideal for women wishing to preserve their fertility and uterine sparing alternative interventions are highly needed.

As intraoperative bleeding from MAP is often massive and dramatically quick resulting in severe maternal morbidity and mortality it is of utmost importance to have a pre-planned approach to this surgical challenge that is effective and swift.

In this study we report on our own centre experience of three procedures to try and reduce intraoperative bleeding and report on its effects on maternal morbidity and mortality postoperatively.

Methods

This is a retrospective study reporting on patients with suspected MAP who had a repeat elective CS in Minia maternity university Hospital, Egypt in the period from 01/01/2012 to 01/01/2017.

The interventions in the study as a part of the trial that was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02590484. Registered 28 October 2015.

Inclusion criteria

Patients included in this study were women with at least one previous caesarean section and placenta previa with suspect MAP who were keen to preserve their fertility if possible and were booked for elective repeat caesarean section. Cases were only included if partial separation occurred at CS resulting in major bleeding. The diagnosis of MAP was confirmed by histopathological study of the removed part of the placenta showing deep invasion of chorionic villi and presence of myometrial fibres (Fig. 1).

Exclusion criteria

Patients who had previous CS/ placenta praevia only with no features of MAP were excluded from this study. We also excluded patients with previous CS with placenta praevia/ accreta who required an emergency caesarean section due to major antepartum haemorrhage (APH) and patients who had preoperative diagnosis of placenta percreta who opted to have an elective hysterectomy or when placenta percreta is confirmed intraoperatively.

The primary outcome for the study was the total volume of blood loss in the intra and postoperative period and the need for hysterectomy. The secondary outcomes were maternal morbidities composite including coagulopathy, need for massive blood transfusion (> 4 units),length of hospital stay > 10 days, and visceral injuries.Other secondary outcomes intended to be reported were maternal mortalities if any present and gynaecological complications as amenorrhoea,intrauterine adhesions.

Diagnostic criteria

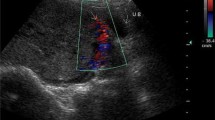

The ultrasound features used for suspicion of MAP were as described previously in literature including one or more of the following;

Loss or thinning (‹1 mm) of the normal hypo-echoic retro-placental myometrial plane or thinning or disruption of the hyper-echoic uterine serosa bladder interface or presence of multiple placental lakes [4].

Patients with equivocal ultrasound diagnosis placenta accreta or suspicion of placenta percreta had magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) scan to confirm or refute the diagnosis.

The MRI features used to diagnose placenta accreta/percreta were as described previously; uterine bulging, heterogeneous signal intensity within placenta, dark intra-placental bands, focal interruption to myometrial wall,invasion of pelvic structures by placental tissue [5].

Management protocol

All patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria had the following protocol of antenatal and intrapartum management.

Antenatal management

All patients with suspected MAP included in this study were admitted to inpatient department for close observations if they had a minor APH and administration of corticosteroids if < 34 weeks gestation. Patients were given hematinic medications during their admission to keep their haemoglobin level above 12 g/dl. At least 4 Cross matched blood units were always kept available. They were booked for elective repeat CS at 37-38 weeks if they remain asymptomatic or their elective CS brought forward to 35–36 weeks if they had any further minor APH.

All patients were fully counselled regarding the risk of bleeding and surgical options at delivery if placenta accreta is confirmed including risk of hysterectomy.

Operative protocol

During the CS, the patients were either in supine or lithotomy position, then opening the skin with a vertical midline or transverse incision. This is followed by opening the anterior abdominal wall in layers. The urinary bladder was dissected downward. For most cases lower segment CS incision was used unless unexpected percreta was noted intraoperatively. After delivery of the foetus a short tentative attempt of delivery of the placenta was performed if it was a suspect MAP to confirm diagnosis. This was not done however if placenta percreta was confirmed intra-operatively.

In the majority of patients encountered in our series we have not encountered a total placenta accreta where partial separation of the placenta is not possible.

In case of partially separated placenta accreta with ensuing bleeding, further action depended on patient’s fertility wishes and elective hysterectomy was done for patients who completed their family however; for patients who wished to preserve their fertility prompt blood transfusion, available uterotonic agents were injected. Patients had one of three intraoperative surgical interventions that evolved during the study period with group A (balloon Tamponade only) being the earliest group and group C being the most recent cases. There was however some chronological overlap over these groups depending on the surgeon’s preference and expertise.

These procedures were used as primary surgical strategy to control bleeding however in case of continued bleeding from the placental bed; a timely emergency hysterectomy was done. Therefore, patients in this study were divided into three groups according to the intraoperative intervention to control bleeding;

Group A

In which patients had only Bakri Balloon inserted transabdominally through the CS incision to tamponade the placenta bed in the lower uterine segment after inflation of the balloon with 250 ml of saline and the balloon tubes were brought vaginally with vaginal packs inserted to keep the balloon in situ and avoid early expulsion. Uterus was closed over the balloon which was kept in for 24 h and removed postoperatively in operating theatre. [6]

Group B

In which patients had bilateral uterine artery ligations as described before [7, 8]. Briefly two large vicryl stitches were passed using a large size 3/8 needle below and lateral to the lower edge of the uterine incision angle in anteroposterior direction and then redirected from back to the front through avascular window in the posterior leaf of the broad ligament just lateral to the uterine border taking care to avoid injury to bowel posteriorly or bladder/ureter anteriorly. The stitches were tied securely anteriorly. This was followed by insertion of the Balloon tamponade as in group A.

Group C

In this group, a combination of bilateral uterine artery ligations and cervical tamponade by elevating the cervix into the uterine cavity using Allis forceps then suturing the anterior and/or posterior cervical lip (s) into the anterior and /or posterior uterine segment (s) depending upon the site of bleeding by two or three simple interrupted stitches. Hegar dilator was inserted from the uterine cavity to confirm patency of the cervical canal. Closure of the uterine incision after control of bleeding (Additional file 1).

Additional file 1: Movie S1 Cervical tamponade in placenta accreta. This is a movie file showing detailed steps of cervical tamponade in which the cervical lips are used to control bleeding in placenta accreta. The video was recorded by the authors of this research article. (MP4 12121 kb)

In group C, Follow up appointments at 3 and 6 months was given after delivery where revision of history, clinical, speculum and ultrasound examinations was performed.

In all patients preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data were collected and used in this report.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were statistically analysed using SPSS software version 20 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, IBM, USA).

Descriptive statistics were done for continuous variables using mean, standard deviation, while they were done for categorical data by number and percentage.

Comparisons for continuous variables were done using one-way ANOVA test and post Hoc Tukey’s Correction and Chi square test was used for categorical variables between groups when the cell contains more than 5, and Fisher exact test when the cell contains less than 5. The level of significance was taken at (P value ≤0.05).

Results

In this study 125 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria during our study period. Group A (balloon Tamponade only) included 42 patients, Group B (balloon Tamponade and uterine artery ligation) 40 patients and group C (uterine artery ligation and cervical tamponade) included 43 patients.

There were no statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics (age, BMI, parity, number of previous caesarean sections, type of placenta previa, location of placenta previa, gestational age at delivery and preoperative haemoglobin) of the patients in the three intervention groups A, B and C as shown in Table 1.

Table 2 shows intra operative and early postoperative observations for the three intervention groups. Group C has the least surgical operation time. Also, the total estimated blood loss (intraoperative and postoperative) was significantly less in Group C compared with Groups A and B (P < 0.001).

Table 3 shows postoperative morbidities in patients with placenta accreta undergoing different procedures. Group C has significantly less need for major blood transfusion and significantly less incidence of coagulopathy. The number of patients requiring admission to ICU and hospitalisation for > 10 days was significantly less in Group C compared to groups A and B. Bladder injuries in Group C were significantly less in Group C compared with Groups A and B. Also, the need for hysterectomy was significantly less in Group C compared with groups A and B. Therefore, the overall morbidity was less and the recovery was quicker for cases in group C was less than the other two groups. There were no maternal mortalities in all groups.

In group C, at 3 months appointment, there were no remarkable clinical, speculum and ultrasound findings in 37 cases. In two patients, the cervical lips were displaced upwards with no pathological coloposcopic and/or hysterocopic findings. Four cases lost follow-up.

Thirty five patients (81.4%) were seen at 6 months appointment, where menstruation was resumed in 33 (76.7%) patients while the other ten patients (23.3%) were amenorrheic that could be explained by lactation or another cause and currently they are under follow-up. Contact details of the hospital and research coordinator(s) were given to the patients in case of experiencing unusual symptoms.

Discussion

This study has shown that prompt use of a combination of bilateral uterine artery ligation and cervical tamponade are simple, cost effective and most effective ways of controlling bleeding due to MAP and has led to significant reduction of maternal morbidity and need for hysterectomy.

Women included in this report were very keen to preserve their fertility and the options that were acceptable to them were either uterine sparing surgical interventions or conservative management. The latter approach (cutting the cord short and leaving placenta in situ) though has recently been recommended [3, 9], was not to feasible in our series due to ensuing bleeding following partial separation of the placenta. Furthermore, the limitation of our experience with conservative management of placenta accreta with uncertainty about risks of sepsis, secondary haemorrhage and later need for hysterectomy as well as the need for lengthy follow-up by compliant patients and possible long-term effect on fertility and gestational trophoblastic disease had made this option less favourable in our own setting.

A number of other studies have reported on the use of various interventions to stop bleeding following partial separation of MAP. These included preoperative insertion of uterine artery catheters to embolise blood vessels in the placental bed [10], internal iliac artery ligation [11], suturing the cervix to the placental bed to occlude bleeding surface [12, 13], the B-Lynch suture [14], insertion of parallel vertical compression sutures [15], a square suturing technique [16], use of multiple 8 compression suturing as a novel procedure to preserve fertility in patients with placenta accreta [17] and Triple-P procedure [perioperative placental localisation, pelvic devascularisation and placental non-separation] involving delivery of the fetus via transverse uterine incision above the upper border of the placenta, myometrial excision and reconstruction of the uterine wall [18, 19] It is likely that there is no single intervention alone will be enough to control the massive bleeding ensuing after separation of MAP. As demonstrated in this study using a combination of the techniques of Balloon tamponade, uterine artery ligation and cervical inversion techniques has been shown to be most effective way of controlling bleeding after MAP.

In 2007, Dawlatly and his colleagues published a case report in which they used the inverted cervical lip(s) to control bleeding from the placental bed and they succeeded to preserve the uterus and patient life [12]. Another study supporting our findings done by Sakhavar et al. who exerts a temporary pressure on the lower segment arteries by using cervical inversion thus reducing blood flow leading to relative hemostasis, after which the placental bed is sutured to control bleeding. After bleeding is controlled, the cervix is returned again to its original position. In such case series, the bleeding was stopped within 3–5 min with no reported major complications, blood transfusions or obstetric hysterectomies [20].

We believe that these techniques should be used as a primary line surgical intervention for controlling bleeding due to MAP. The techniques described in this report are readily available in most settings, easy to learn and apply and do not require sophisticated equipment as in uterine artery embolization or special skills and expertise as in ligation of internal iliac artery. These surgical measures should be provided as a part of a comprehensive preoperative and intraoperative care bundle. We suggest using a stepwise approach of intraoperative control of bleeding utilizing combination of uterine artery ligation, balloon tamponade and use cervical inversion as first step. This can be escalated to other techniques as internal iliac artery ligation and/or uterine artery embolization if first line measures are inadequate with prompt timely recourse to hysterectomy as a life-saving measure if all other measures proved futile.

The strenghths of our study is its comprehensive preoperative diagnostic work-up and comprehensive reporting on techniques with significant impact on maternal outcomes and relatively large sample size for this uncommon obstetric problem. Our study is limited by its retrospective nature which could have introduced an element of performance bias. This may have led to the apparent shortening of operating time in the group C as these patients were the most recent group with possible better performance as experience accumulating in dealing with similar emergencies in the other two groups. Although all groups were not significantly different in known baseline confounding variables it is possible that with accumulating radiological experience and more confident diagnosis of MAP, Ultrasound -confirmed cases had more directed counselling for hysterectomy leaving only suspected cases with partial accreta in the late stages of study period. This may have introduced an element of selection bias.

A prospective controlled study to address these limitations however due to the uncommon nature of the problem and impact of other factors (as patient’s preference and clinician’s/centre experience and local protocols) would be difficult to conduct.

Conclusions

The combination of bilateral uterine artery ligation and using the cervix as a natural tamponade are very effective and simple methods in controlling bleeding resulting from partially separated MAP. Use of these surgical techniques in combination with other preoperative and intraoperative measures have led to less risk of maternal morbidities.

Abbreviations

- APS:

-

Antepartum haemorrhage

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- MAP:

-

Morbidly adherent placenta

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonant imaging

- PPH:

-

Postpartum haemorrhage

References

Silver RM, Barbour KD. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: Accreta, Increta, and Percreta. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(2):381–402.

Silver RM, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226–32.

Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, et al. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and management: green-top guideline no. 27a. BJOG. 2019;126(1):e1–e48.

Cali G, et al. Morbidly adherent placenta: evaluation of ultrasound diagnostic criteria and differentiation of placenta accreta from percreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(4):406–12.

Lax A, et al. The value of specific MRI features in the evaluation of suspected placental invasion. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(1):87–93.

Frenzel D, et al. The use of the “tamponade test” to stop massive obstetric haemorrhage in placenta accreta. BJOG. 2005;112(5):676–7.

Ferrazzani S, et al. Conservative management of placenta previa-accreta by prophylactic uterine arteries ligation and uterine tamponade. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;25(4):400–3.

Shahin AY, et al. Bilateral uterine artery ligation plus B-Lynch procedure for atonic postpartum hemorrhage with placenta accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;108(3):187–90.

Fitzpatrick KE, et al. The management and outcomes of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta in the UK: a population-based descriptive study. BJOG. 2014;121(1):62–70 discussion 70-1.

Shrivastava V, et al. Case-control comparison of cesarean hysterectomy with and without prophylactic placement of intravascular balloon catheters for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):402 e1–5.

Carnevale FC, et al. Perioperative temporary occlusion of the internal iliac arteries as prophylaxis in cesarean section at risk of hemorrhage in placenta accreta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(4):758–64.

Dawlatly B, et al. Using the cervix to stop bleeding in a woman with placenta accreta: a case report. BJOG. 2007;114(4):502–4.

El Gelany SAA, Abdelraheim AR, Mohammed MM, et al. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0731-9.

B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, Abu I, Cowen MJ. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum haemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:372–5.

Hwu YM, Chen CP, Chen HS, Su TH. Parallel vertical compression sutures: a technique to control bleeding from placenta praevia or accreta during cesarean section. Bjog. 2005;112:1420–3.

Tjalma WA, Jacquemyn Y. Compression sutures instead of emergency peripartum hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;118:258 author reply 258–9.

Shazly SA, Badee AY, Ali MK. The use of multiple 8 compression suturing as a novel procedure to preserve fertility in patients with placenta accreta: case series. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52:395–9.

Teixidor Viñas M, Belli AM, Arulkumaran S, Chandraharan E. Prevention of postpartum hemorrhage and hysterectomy in patients with morbidly adherent placenta: a cohort study comparing outcomes before and after introduction of the triple-P procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:350–5.

Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Chandraharan E, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Jauniaux E, FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Conservative management. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(3):291–8.

Sakhavar N, Heidari Z, Mahmoudzadeh-Sagheb H. Cervical inversion as a novel technique for postpartum hemorrhage management during cesarean delivery for placenta previa accreta/increta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):122–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professors Mohamed Hany, Mohamed Abdallah, Neveen M Noureldin, M Tawfique, and Hossam Eldin Shawky (head of the department), for their valuable contributions and advice during preparation of the manuscript. Our sincere gratitude goes to the management and staff of the faculty of Medicine, Minia maternity and children university hospital during the study period for their support and for assisting with data collection.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the manuscript. SE, EK and MK conceptualised the study. SE, ARA and MK were involved in the primary research concept and design of the study, initial data collection, writing, and data analysis. All authors participated in the study design, planning of analysis, and interpretation of results. SE, ARA, EI, AKA, AY, HH, KG, MM, EK and MK performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Minia University Hospital on 4/12/2011 (Registration number: MUH14368).

Participants signed a written informed consent about the procedure(s), the risks including occurrence of massive postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), blood transfusion, the use of conservative methods and the possibility of proceeding to emergency hysterectomy with the accompanying risk of injury to adjacent structures as the bladder, ureters and bowel.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

El Gelany, S., Ibrahim, E.M., Mohammed, M. et al. Management of bleeding from morbidly adherent placenta during elective repeat caesarean section: retrospective -record -based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 106 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2244-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2244-4