Abstract

Background

Maternal diaphragmatic hernias identified during pregnancy are rare and pose significant management challenges with regards to timing and mode of both delivery and hernia repair.

Case presentation

We describe a case of a maternal diaphragmatic hernia diagnosed at 31 weeks gestation in the setting of acute upper abdominal pain. Due to no evidence of visceral compromise and a stable maternal condition, the patient was conservatively managed, allowing for further foetal maturation. Delivery by caesarean section occurred following concerns of malnutrition and partial bowel obstruction. This was followed by immediate surgical repair of the hernia. The patient had an uncomplicated recovery.

Conclusion

Maternal diaphragmatic hernias in pregnancy require multidisciplinary care and individualised management in order to allow for the optimal outcome for mother and foetus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) result from failure of closure of the pleuroperitoneal folds in the posterolateral (Bochdalek) or substernal (Morgagni) portion of the diaphragm [1]. The majority of CDH are diagnosed antenatally and surgically repaired in the neonatal period. Those that are not diagnosed in utero often present with respiratory or intestinal symptoms in the first few years of life [2]. Therefore, it is relatively uncommon for diaphragmatic hernias to be diagnosed in adulthood [3]. First presentation in pregnancy is scarcely described in the literature and the management largely involves immediate surgical repair. We describe a rare case of an undiagnosed maternal CDH manifesting late in pregnancy. In this scenario, we explore the possibility of expectant management and the potential multidisciplinary challenges that may arise from this approach.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old gravida 2 para 0 presented at 31 + 3 weeks gestation with sudden onset, unprovoked, epigastric and left sided pleuritic chest pain. This was associated with nausea, vomiting and shortness of breath. Her bowels had opened that day and she was passing flatus. She denied any uterine tightenings, urinary symptoms or vaginal loss and reported normal foetal movements.

The patient was an otherwise well South Asian woman with good social supports and no significant medical, surgical or family history. She did however, have a similar presentation at 13 weeks gestation and was diagnosed with left lower lobe pneumonia and a possible empyema on chest x-ray. (Fig. 1) Bronchoscopy and washings at this time were negative and she was managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics. Her pregnancy then progressed uneventfully.

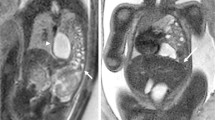

On presentation, her observations were unremarkable with oxygen saturations at 100% on room air, a respiratory rate of 20 and a normal cardiotocograph (CTG). She was, however, in significant distress secondary to pain, despite opiate analgesia. Respiratory examination revealed decreased breath sounds on the left hand side and abdominal palpation showed left upper quadrant and epigastric tenderness with normal bowel sounds and no signs of peritonism. Routine biochemical investigations including a full blood count, biochemistry and lactate were unremarkable. A chest x-ray, however, revealed evidence of a raised or ruptured left hemi-diaphragm with bowel visible in the chest. (Fig. 2) A subsequent CT chest confirmed the diagnosis of a large left diaphragmatic defect with stomach, small and large bowel, and spleen in the chest cavity. (Fig. 3) There was no evidence of a gastric volvulus or bowel ischemia. On retrospective review of her previous chest x-ray at 13 weeks gestation, what was originally presumed to be an empyema likely represented a small diaphragmatic hernia. (Fig. 1) On further questioning, the patient reported that she was asymptomatic prior to pregnancy and had no prior chest or abdominal imaging for comparison.

The patient received a course of steroids for foetal lung maturation and was transferred to our tertiary centre for consideration of urgent delivery and repair of the diaphragmatic defect. On arrival, the patient was found to be haemodynamically stable and her pain was now better controlled with regular doses of opiate analgesia. Given no immediate evidence of bowel obstruction, visceral ischaemia, respiratory compromise or concerns for foetal wellbeing were present, a decision was made, jointly by the surgical and obstetric teams, to conservatively manage the patient. Delivery and repair were planned ideally for after 34 weeks gestation, or in the event of maternal or foetal deterioration. Due to her inability to tolerate sufficient oral intake, a nasogastric tube was inserted and the patient commenced on nasogastric feeds on day five of admission with dietician input. In order to meet nutritional requirements of pregnancy, feeds were titrated from 10 ml/hr. with the aim to achieve 60 ml/hr. However, the patient was unable to tolerate the required feed volume, experiencing nausea, pain and increased nasogastric aspirates. Due to the inability to meet nutritional requirements and the possibility of a partial intestinal obstruction, a decision was subsequently made for an earlier delivery at 32 + 3 weeks gestation.

We performed a lower uterine segment caesarean section followed by a left thoracotomy on day 7 of admission. The caesarean section was uncomplicated and a liveborn female infant weighing 1731 g was delivered. The thoracotomy identified a likely Bochdalek hernia involving stomach, small bowel, colon, appendix, spleen and omentum. The contents were reduced and the defect was repaired with four figure of eight Prolene sutures. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on day nine post-operatively. The neonate was admitted to the special care nursery due to issues of prematurity, specifically, mild respiratory distress, difficulty establishing feeds and jaundice.

Discussion and conclusions

The presentation of maternal diaphragmatic hernias in pregnancy is a rare phenomenon and poses a management dilemma with regards to timing of delivery and repair. Increase in intra-abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus likely contributes to more severe presentations in pregnancy, more challenging operative management and possibly greater morbidity [4]. Our literature review identified 56 cases of maternal diaphragmatic hernias presenting in pregnancy. Of the 56 cases identified, 54% presented after 24 weeks gestation, [1, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] 21% prior to 24 weeks, [2, 23, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], 20% during labour or postpartum [33, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] and 5% did not report gestation. The patients predominantly reported symptoms of abdominal or chest pain (84%), vomiting (60%) and dyspnoea (41%). There were six maternal deaths (11%) [19, 23, 33, 49] and eleven foetal deaths (19%) [9, 10, 12, 18, 23, 29, 32,33,34, 50].

Of those that presented prior to 24 weeks gestation, the majority underwent an immediate surgical repair for reasons of cardiorespiratory compromise, visceral obstruction or visceral ischaemia. Subsequently, the pregnancies were managed expectantly to term and then delivered via caesarean section or vaginal delivery. Of those that presented after 24 weeks gestation, 56% were managed with immediate surgical repair and 44% had a delay in repair either due to a delay in diagnosis or to allow for foetal maturation. Duration of expectant management ranged from 1 to 2 days to 10 weeks (mean of 13 days). Again, the main reasons for delivery and surgical management included respiratory compromise, visceral obstruction or visceral ischaemia.

Our case adds to the body of literature that explores the option of delaying delivery and surgical repair to allow for foetal maturation. One of the potential challenges of expectant management is achieving adequate nutrition in pregnancy. Recommendations for caloric requirements in pregnancy are 2200-2900 kcal/day with 1.1 g/kg/day of protein, 175 g/day of carbohydrates, and additional requirements of various micronutrients [51, 52]. Malnutrition for prolonged periods can be associated with intrauterine growth restriction, increased perinatal morbidity and mortality, maternal weight loss, electrolyte imbalances and vitamin deficiencies [53]. Our patient was unable to tolerate oral or nasogastric feeds due to a likely partial obstruction from the large hernia and she remained essentially fasting for seven days. The alternative option was to consider total parenteral nutrition (TPN). However, TPN is an invasive procedure that can be associated with a variety of complications including sepsis, issues with central intravenous catheter insertion (obstruction, thrombosis, pneumothorax) and metabolic side effects (glycaemic derangements, electrolyte imbalances and liver dysfunction) [54]. Therefore, while we aimed to achieve a further two to three weeks in gestation, we believed the potential complications of malnourishment and possible side effects of TPN outweighed the benefits of advancing gestation. As a result, we opted for earlier delivery at 32 weeks. This is consistent with literature, where in the majority of reports of maternal diaphragmatic hernias, clinicians opted for surgical management and delivery within a few days. The main reason for expectant management was to allow time for steroid loading and foetal maturation. However, many subsequently justified pre-term delivery and repair due to concerns for maternal complications.

With regards to the mode of delivery, our literature review showed that only seven cases (23%) presenting after 24 weeks achieved vaginal delivery. Three of these cases were in the context of preterm labour or foetal death in utero. In our situation we chose an elective caesarean section due to the size of the defect, an unfavourable cervix in a nulliparous woman and the possibility of further deterioration in labour.

Conclusion

In summary, maternal diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy is a rare presentation, which requires multidisciplinary input for optimal management. While expectant management should be considered, the potential challenges of malnutrition, visceral obstruction and respiratory compromise need to be carefully evaluated.

Abbreviations

- CDH:

-

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

- CTG:

-

Cardiotocograph

- TPN:

-

Total Parenteral Nutrition

References

Fleyfel M, Provost N, Ferreira JF, Porte H, Bourzoufi K. Management of diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(3):501–3.

Debergh I, Fierens K. Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia with incarcerated bowel during pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44(4):753–6.

Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek's hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(2):363–6.

Brygger L, Fristrup CW, Harbo FS, Jorgensen JS. Acute gastric incarceration from thoracic herniation in pregnancy following laparoscopic antireflux surgery. BMJ case reports. 2013;2013

Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Maheshkumaar GS, Parthasarathi R. Laparoscopic mesh repair of a Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia with acute gastric volvulus in a pregnant patient. Singap Med J. 2008;49(1):e26–8.

Kawashima K, Nakahata K, Negoro T, Nishikawa K. "spontaneous" rupture of the maternal diaphragm. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):445.

Osman I, McKernan M, Rae DW. Normal vaginal delivery following rupture of the maternal diaphragm in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(6):625–7.

Agarwal P, Ash A. Gastric volvulus: a rare cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(3):313–4.

Eglinton T, Coulter GN, Bagshaw P, Cross L. Diaphragmatic hernias complicating pregnancy. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(7):553–7.

Hunter JD, Nimmagadda J, Quayle A. Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing cardiovascular collapse during pregnancy. Br J Hosp Med. 2009;70(3):166–7.

Wieman E, Pollock G, Moore BT, Serrone R. Symptomatic right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in the third trimester of pregnancy. JSLS. 2013;17(2):358–60.

Rabinovici J, Czerniak A, Rabau MY, Avigad I, Wolfstein I. Diaphragmatic rupture in late pregnancy due to blunt injury. Injury. 1986;17(6):416–7.

Sano A, Kato H, Hamatani H, Sakai M, Tanaka N, Inose T, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia with ischemic bowel obstruction in pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38(9):836–40.

Genc MR, Clancy TE, Ferzoco SJ, Norwitz E. Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 2):1194–6.

Hernández-Aragon M R-LL, Crespo-Esteras R, Ruiz-Campo L, Adiego-Calvo I, Campillos-Maza J, Castán-Mateo S. Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy in the third trimester: case report. Obstet Gynaecol Cases - Reviews 2015;2(5).

Ngai I, Sheen JJ, Govindappagari S, Garry DJ. Bochdalek hernia in pregnancy. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012

Islah MA, Jiffre D. A rare case of incarcerated bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia in a pregnant lady. Med J Malaysia. 2010;65(1):75–6.

Wolfe CA, Peterson MW. An unusual cause of massive pleural effusion in pregnancy. Thorax. 1988;43(6):484–5.

Rifki Jai S, Bensardi F, Hizaz A, Chehab F, Khaiz D, Bouzidi A. A late post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia revealed during pregnancy by post-partum respiratory distress. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276(3):295–8.

Yoshizu A, Kamiya K. Diaphragmatic hernia complicated with perforated stomach during pregnancy. Kyobu geka the Japanese journal of thoracic. Surgery. 2011;64(6):487–90.

Rajasingam D, Kakarla A, Jones A, Ash A. Strangulated congenital diaphragmatic hernia with partial gastric necrosis: a rare cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(9):1587–9.

Kurzel RB, Naunheim KS, Schwartz RA. Repair of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(6 Pt 1):869–71.

Indar A, Bornman PC, Beckingham IJ. Late presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(6):392–3.

Luu TD, Reddy VS, Miller DL, Force SD. Gastric rupture associated with diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(5):1908–10.

Bernhardt LC, Lawton BR. Pregnancy complicated by traumatic rupture of the diaphragm. Am J Surg. 1966;112(6):918–22.

Riad M, Shervington J, Woodward Z. Maternal death due to ruptured diaphragmatic hernia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29(7):669–70.

Benson CC, Valente AM, Economy KE, Hoffman-Sage Y, Bevilacqua LM, Podovei M, et al. Discovery and management of diaphragmatic hernia related to abandoned epicardial pacemaker wires in a pregnant woman with {S,L,L} transposition of the great arteries. Congenit Heart Dis. 2012;7(2):183–8.

Henzler M, Martin ML, Young J. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(4):350–3.

Chen X, Yang X, Cheng W. Diaphragmatic tear in pregnancy induced by intractable vomiting: a case report and review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1822–4.

Schwentner L, Wulff C, Kreienberg R, Herr D. Exacerbation of a maternal hiatus hernia in early pregnancy presenting with symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum: case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(3):409–14.

Barbetakis N, Efstathiou A, Vassiliadis M, Xenikakis T, Fessatidis I. Bochdaleck's hernia complicating pregnancy: case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(15):2469–71.

Chen Y, Hou Q, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Xi M. Diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy: a case report with a review of the literature from the past 50 years. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(7):709–14.

Dudley AG, Teaford H, Gatewood TS Jr. Delayed traumatic rupture of the diaphragm in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(3 Suppl):25S–7S.

Flamee P, Pregardien C. Tension gastrothorax causing cardiac arrest. CMAJ. 2012;184(1):E82.

Hanekamp LA, Toben FM. A pregnant woman with shortness of breath. Neth J Med. 2006;64(3):84. 95

Morcillo-Lopez I, Hidalgo-Mora JJ, Baamonde A, Diaz-Garcia C. Gastric and diaphragmatic rupture in early pregnancy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;11(5):713–4.

Toorians AW, Drost-Driessen MA, Snellen JP, Smeets RW. Acute hernia of Bochdalek during pregnancy. Hyperemesis for the first time in a third pregnancy? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1992;71(7):547–9.

Ting JY. Difficult diagnosis in the emergency department: hyperemesis in early trimester pregnancy because of incarcerated maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20(5):441–3.

Hamaji M, Burt BM, Ali SO, Cohen DM. Spontaneous diaphragm rupture associated with vaginal delivery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61(8):473–5.

Hamoudi D, Bouderka MA, Benissa N, Harti A. Diaphragmatic rupture during labor. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13(4):284–6.

Hill R, Heller MB. Diaphragmatic rupture complicating labor. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(4):522–4.

Kaloo PD, Studd R, Child A. Postpartum diagnosis of a maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41(4):461–3.

Lacayo L, Taveras JM 3rd, Sosa N, Ratzan KR. Tension fecal pneumothorax in a postpartum patient. Chest. 1993;103(3):950–1.

Maddox PR, Mansel RE, Butchart EG. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm: a difficult diagnosis. Injury. 1991;22(4):299–302.

Mutanen A, Sandelin H, Nieminen A, Huusari H, Toikkanen V. Diaphragmatic rupture: case report of a rare complication of labor. Duodecim; laaketieteellinen aikakauskirja. 2015;131(8):753–6.

Rubin S, Sandu S, Durand E, Baehrel B. Diaphragmatic rupture during labour, two years after an intra-oesophageal rupture of a bronchogenic cyst treated by an omental wrapping. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(2):374–6.

Pai SRN, Balu K, Madhusudhanan J. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy: a case report. Internet J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;9(1)

Gimovsky ML, Schifrin BS. Incarcerated foramen of Bochdalek hernia during pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1983;28(2):156–8.

Zimmermann HD, Stracke H. Sudden maternal death in late pregnancy: congenital diaphragmatic defect causing prolapse of the intestine into the thoracic cavity (author's transl). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1977;37(10):882–6.

Ali SA, Haseen MA, Beg MH. Agenesis of right diaphragm in the adults: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2014;56(2):121–3.

Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: A background paper. Wellington: Ministry of Health 2006.

Kaiser L, Allen LH, American Dietetic A. Position of the American dietetic association: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(3):553–61.

Christian P, Mullany LC, Hurley KM, Katz J, Black RE. Nutrition and maternal, neonatal, and child health. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(5):361–72.

Parenteral nutrition pocketbook: for adults. In: Innovation AfC, editor.: NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR was primarily involved in manuscript preparation. KP and AK were primarily involved in editing this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reddy, M., Kroushev, A. & Palmer, K. Undiagnosed maternal diaphragmatic hernia – a management dilemma. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 237 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1864-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1864-4