Abstract

Background

Mirror syndrome (MS) is a rare obstetric condition usually defined as the development of maternal edema in association with fetal hydrops. The pathogenesis of MS remains unclear and may be misdiagnosed as pre-eclampsia.

Case presentation

We report a case series of MS in which fetal therapy (intrauterine blood transfusion and pleuroamniotic shunt) resulted in fetal as well as maternal favourable course with complete resolution of the condition in both mother and fetus.

Conclusions

Our case series add new evidence to support that early diagnosis of MS followed by fetal therapy and clinical maternal support are critical for a good outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mirror syndrome (MS) is a rare complication of fetal hydrops appearing as a triple edema (fetal, placental as well as maternal) [1], in which the mother “mirrors” the hydropic fetus. This syndrome was first described in 1892 by the Scottish obstetrician John William Ballantyne [2].

There have been multiple feto-placental diseases related to MS, that can be classified into diverse groups based on different etiologies [3]: cardiac failure associated with fetal anemia (e.g. Parvovirus B19 [4], erytroblastosis [5], fetal alloimmune thrombocytopenia [6], hemoglobin Bart’s disease [7]); high-output cardiac failure associated with shunting (e.g. chorioangioma [8], twin to twin transfusion syndrome [9,10,11,12,13]); and fetal anomalies (e.g. fetal arrhythmias [14], CHAOS syndrome [15]).

MS maternal clinical picture includes peripheral edema, uterine distension and rapid weight gain [3]. Those nonspecific clinical features may lead to a misdiagnosis of pre-eclampsia, delaying diagnosis and therapy of MS and worsening fetal and maternal condition. MS does not usually present with hypertension, but blood pressure can be elevated and proteinuria can appear, resembling the clinical features of pre-eclampsia [3, 16]. Like in pre-eclampsia, laboratory findings may include proteinuria, low platelet count and elevation of creatinine, hepatic enzymes and uric acid levels [3].

The treatment of choice for MS is the resolution of the fetal hydrops. If correction of the fetal condition is not possible, delivery usually results in a favourable maternal outcome [17]. Vaginal delivery may be preferred, but complications as maternal pulmonary edema or deterioration of the fetal condition can lead to an emergent caesarean section [18,19,20].

Case presentation

Case 1

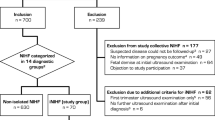

A 31-year-old G1P0 caucasian woman was referred to our centre at 27 + 2 gestational weeks for evaluation of fetal hydrops. Her medical and obstetric record as well as the previous fetal ultrasound at 20 weeks were unremarkable.

On admission the patient was normotensive, with stable vital signs. Physical examination showed a significant edema in both lower extremities and sacrum. Blood analysis results revealed a hemoglobin of 105 g/L, and a hematocrit of 28.8% with normal platelet count. Liver function test was abnormal: ALT 68 mU/ml (N < 40 mU/ml), AST 44 mU/ml (N < 37 mU/ml). LDH was elevated (240 UI/L; N < 225 UI/L) as well as uric acid levels (8.4 mg/dL; N < 7 mg/dL). Renal function was normal with a creatinine of 0.87 mg/dL (N < 1.1 mg/dL) and a urea of 39 mg/dL (N < 40 mg/dL). Her 24-h urinary protein excretion was 2925 mg.

Ultrasound revealed a single fetus with hydrops including severe ascites, pericardial effusion, subcutaneous tissue edema, a slightly thickened placenta (Figure 1), and normal amniotic fluid index (AFI). No fetal anomalies were detected. Middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV) value was 77.5 cm/s (2.19 MoM [21, 22]) with an estimated hemoglobin of 38.6 g/L (0.31 MoM [22]). The EFW was 1.073 g. Initial evaluation of fetal anemia included indirect Coomb’s test, serology for Parvovirus B19 and TORCH. Fetus was diagnosed as having a hydrops related to severe anemia and a MS was diagnosed.

Forty-eight hours following patient admission, intrauterine blood transfusion (IBT) was performed as described elsewhere [8]. Before the procedure, a single course of corticosteroid therapy was administered to accelerate fetal pulmonary maturity, and tocolysis with atosiban was started. During the intervention, fetal blood samples for genetic, anemia and infection studies were obtained, and a Kleihauer-Betke test was requested. Following IBT, fetal hemoglobin increased from 43 g/L to 109 g/L, and fetal hematocrit from 14% to 34%. Anti-D Ig 300 μg IM was administered after transfusion to prevent Rh(D) alloimmunization. The next day MCA-PSV value decreased to 36.9 cm/s (1.02 MoM) [21, 22]. In both maternal and fetal blood Indirect Immunofluorescence Test (IIFT) a positive IgM for Parvovirus B19 were found, confirming the etiology of the fetal anemia.

Fetal and maternal follow up revealed a progressive reduction of fetal hydrops (Figure 2) together with a progressive resolution of maternal clinical picture including normalization of laboratory tests.

At 29 + 4 gestational weeks, a preterm premature rupture of membranes occurred. At 34 gestational weeks a healthy male infant was born by vaginal delivery, with Apgar score of 8/9/10 at 1, 5 and 10 min. Both mother and child were discharched without complications and are currently doing well 2 years after delivery.

Case 2

A 37-year-old G1P0 caucasian woman was admitted to our centre at 31 gestational weeks due to nausea, vomiting and severe abdominal pain refractory to the medical treatment. Premature labor with progressive cervical shortening was diagnosed and tocolysis with atosiban was started. Physical examination showed a significant skin edema in both lower extremities. Her vital signs and laboratory results were within normal range except for anemia (hemoglobin 89 g/L). Further laboratory test showed a marked increase in C-reactive protein to 82.3 mg/L (N < 5 mg/dL).

Fetal ultrasound revealed a bilateral hydrothorax with a structural and functionally normal heart and vessels. A large hyperechoic placenta and placental edema were observed as well. No fetal anomalies were detected, and AFI was in normal range. MCA-PSV was 51.9 cm/s (1.21 MoM), consistent with an estimated fetal hemoglobin of 111.1 g/L (0.85 MoM [22]).

MS was diagnosed and a pleuroamniotic shunt (rocket catheter) was placed in right hemithorax to resolve fetal hydrops. Shunting was followed by bilateral lung parenchyma expansion (Figure 3).

On post-operative day#1, a deterioration of maternal clinical status with respiratory distress associated with increasing edema and diuresis volume reduction were observed. In addition, maternal echocardiography showed evidence of moderate pericardial effusion and tricuspid insufficiency. Treatment was started with furosemide, spironolactone, seroalbumine and potassium. In the next 72 h following maternal treatment and fetal hydrops resolution, an improvement of maternal clinical condition ocurred, with progressive disappearance of maternal peripheral edema, respiratory distress and anemia.

At 35 + 2 gestational weeks preterm premature rupture of membranes occurred, followed by delivery of a healthy male newborn with Apgar score 10/10/10 at 1, 5 and 10 min. At birth no lesions in newborn costal grid related to intrauterine shunt placement were observed. Both mother and newborn were discharged without complications and are currently doing well one year after delivery.

Discussion and conclusions

MS is a condition wherein the mother “mirrors” the edema present in the fetus. This entity was first described in association with rhesus-immunization, although MS is most commonly associated with non-immune fetal hydrops (NIHF) of an unknown etiology [19]. Anemia related to Parvovirus B19 is the most frequent reported infectious cause of NIHF. Therefore, complete serology including Parvovirus B19 is mandatory in the differential diagnosis of the fetal hydrops etiology related to anemia.

MS has many similarities to pre-eclampsia [23], sharing clinical features that may be caused in both cases by an imbalance between angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors [24]. In pre-eclampsia there exists evidence of placental underperfusion caused by failure of trophoblastic invasion into the spiral arteries, with a subsequent increasing of circulating sFLT-1 levels and decreasing of PlGF levels [25, 26], being the second one a mechanism proposed as well as responsible for the maternal clinical findings in MS [27,28,29,30,31].

The association of edema, oliguria, and hemodilution might be characteristic of MS [32]. In addition, it has been suggested that the presence of hemodilution might be criteria for diagnosis of MS, as opposed to pre-eclampsia with low haematocrit [33]. MS does not usually present with oligohydramnios or hypertension [34], and unlike pre-eclampsia may be reversed if fetal hydrops is resolved. Fetal prognosis in MS is usually worse than in pre-eclampsia, resulting in many cases in intrauterine fetal demise [3], and being 56% the currently reported rate of intrauterine fetal death in MS [33].

In MS fetal hydrops successful therapy has been claimed as a key step to maternal clinical picture resolution [3, 5, 9, 10, 12, 31, 35]. According to a recent systematic review, interventions to correct the fetal hydrops related to anemia were significantly associated with improved fetal survival [35]. However, sometimes delivery is required when it is not possible to perform fetal therapy or when it is not successful [3, 12, 17, 20, 33, 36,37,38]. Different strategies have been described for the resolution of fetal hydrops, [3, 5, 9, 13, 14, 31, 39]. In our case series, fetal therapy (IBT and pleuroamniotic shunt) led to a slow but consistent reversal of maternal clinical picture following fetal hydrops resolution, resulting in a good fetal and maternal outcome.

Current data and experience from clinical practice support that fetal hydrops therapy, regardless etiology, improves fetal survival as well as maternal evolution in MS. The cases we described show the need for an early diagnosis of MS, followed by an adequate treatment of the fetal condition, which improves maternal condition as well as perinatal morbidity and mortality. When the underlying fetal insult is corrected, we can expect a slow but sustained recovery of maternal condition, that may require an adequate intensive support.

Abbreviations

- AFI:

-

Amniotic Fluid Index

- EFW:

-

Estimated Fetal Weight

- IBT:

-

Intrauterine Blood Transfusion

- IIFT:

-

Indirect Immunofluorescence Test

- MCA-PSV:

-

Middle Cerebral Artery Peak Systolic Velocity

- MS:

-

Mirror Syndrome

- NIHF:

-

Non-Immune Fetal Hydrops

- NST:

-

Nonstress Test

References

Ballantyne KIH. triple edema. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:115–20.

Ballantyne JW. The disease and deformities of the fetus. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd; 1892.

Braun T, Brauer M, Fuchs I, Czernik C, Dudenhausen JW, Henrich W, Sarioglu N. Mirror syndrome: a systematic review of fetal associated conditions, maternal presentation and perinatal outcome. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27(4):191–203.

Desvignes F, Bourdel N, Laurichesse-Delmas H, Savary D, Gallot D. Ballantyne syndrome caused by materno-fetal parvovirus B19 infection: about two cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2011;40(3):262–6.

Valsky D, Daum H, Yagel S. Reversal of mirror syndrome after prenatal treatment of diamond-Blackfan anemia. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27(12):1161–4.

Jain V, Clarke G, Russell L, McBrien A, Hornberger L, Young C, Chandra SA. Case of alloimmune thrombocytopenia, hemorrhagic anemia-induced fetal hydrops, maternal mirror syndrome, and human chorionic gonadotropin- induced thyrotoxicosis. AJP Rep. 2013;3(1):41–4.

Zhang Z, Xi M, Peng B, You Y. Mirror syndrome associated with fetal hemoglobin Bart’s disease: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288(5):1183–5.

García-Díaz L, Carreto P, Costa-Pereira S, Antiñolo G. Prenatal management and perinatal outcome in giant placental chorioangioma complicated with hydrops fetalis, fetal anemia and maternal mirror syndrome. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12:72.

Masakuzu M, Masahiko N, Murata S, Sumie M, Sugino N. Resolution of mirror syndrome after successful fetoscopic laser photocoagulation of communicating placental vessels in severe twin–twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28(12):1167–8.

Chang YL, Chao AS, Chang SD, Wang CN. Mirror syndrome after fetoscopic laser therapy for twin-twin transfusion syndrome due to transient donor hydrops that resolved before delivery. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2014;59(1- 2):90–2.

Chai H, Fang Q, Huang X, Zhou Y, Luo Y. Prenatal management and outcomes in mirror syndrome associated with twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(12):1213–8.

Brandão AM, Domingues AP, Fonseca EM, Miranda TM, Moura JP. Mirror syndrome after Fetoscopic laser treatment - a case report. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2016;38(11):576–9.

Nassr AA, Shamshirsaz AA, Belfort MA, Espinoza J. Spontaneous resolution of mirror syndrome following fetal interventions for fetal anemia as a consequence of twin to twin transfusion syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;208:110–1.

Sherer DM, Sadovksy E, Menashe M, Mordel N, Rein AJ. Fetal ventricular tachycardia associated with nonimmunologic hydrops fetalis. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:292–4.

Ren S, Bhavsar T, Wurzel JCHAOS. In the mirror: Ballantyne (mirror) syndrome related to congenital high upper airway obstruction syndrome. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2012;31(6):360–4.

Paternoster DM, Manganelli F, Minucci D, Nanhornguè KN, Memmo A, Bertoldini M, Nicolini U. Ballantyne syndrome: a case report. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21(1):92–5.

Heyborne KD, Chism DM. Reversal of Ballantyne síndrome by selective second-trimester fetal termination. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(4):360–2.

Tayler E, DeSimone C. Anesthetic management of maternal mirror syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2014;23(4):386–9.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (SMFM), Norton ME, Chauhan SP, Dashe JS. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) clinical guideline #7: nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):127–39.

Li H, Gu WR. Mirror syndrome associated with heart failure in a pregnant woman: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(9):16132–6.

Detti L, Oz U, Guney I, Ferguson JE, Badaho-Singh RO, Mari G. Collaborative Group for Doppler Assessment of the blood velocity in anemic fetuses. Doppler ultrasound velocimetry for timing the second intrauterine transfusion in fetuses with anemia from red cell alloimmunization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(5):1048–51.

Mari G, Deter RL, Carpenter RL, Rahman F, Zimmerman R, Moise KJ Jr, Dorman KF, Ludomirsky A, González R, Gómez R, Oz U, Detti L, Copel JA, Badaho-Singh R, Berry S, Martínez-Poyer J, Blackwell SC. Noninvasive diagosis by Doppler ultrasonography of fetal anemia due to maternal red-cell alloimmunization. Collaborative Group for Doppler Asessment of the blood velocity in anemic fetuses. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(1):9–14.

Wu LL, Wang CH, Li ZQ. Clinical study of 12 cases with obstetric mirror syndrome. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2012;47(3):175–8.

Bixel K, Silasi M, Zelop CM, Lim KH, Zsengeller Z, Stillman IE, Rana S. Placental origins of angiogenic dysfunction in mirror syndrome. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012;31(2):211–7.

Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):649–58.

Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(7):672–83.

Prefumo F, Pagani G, Fratelli N, Benigni A, Frusca T. Increased concentrations of antiangiogenic factors in mirror syndrome complicating twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30(4):378–9.

De Oliveira L, Sass N, Boute T, Moron AF. sFlt-1 and PlGF levels in a patient with mirror syndrome related to cytomegalovirus infection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;158(2):366–7.

Stepan H, Faber R. Elevated sFlt1 level and preeclampsia with parvovirus-induced hydrops. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1857–8.

Lee JY, Hwang JY. Mirror syndrome associated with fetal leukemia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(6):971–4.

Llurba E, Marsal G, Sánchez O, Domínguez C, Alijotas-Reig J, Carreras E, Cabero L. Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors before and after resolution of maternal mirror syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(3):367–9.

Carbillon L, Oury JF, Guerin JM, Azancot A, Blot P. Clinical biological features of Ballantyne syndrome and the role of placental hydrops. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997;52(5):310–4.

Espinoza J, Romero R, Nien JK, Kusanovic JP, Richani K, Gomez R, Kim CJ, Mittal P, Gotsh F, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan S. A role of the anti-angiogenic factor sVEGFR-1 in the ‘mirror syndrome’ (Ballantyne’s syndrome). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19(10):607–13.

Giacobbe A, Grasso R, Interdonato ML, Laganà AS, Valentina G, Triolo O, Mancuso A. An unusual form of mirror syndrome: a case report. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(3):313–5.

Allarakia S, Khayat HA, Karami MM, Aldakhil AM, Kashi AM, Algain AH, Khan MA, Alghifees LS, Alsulami RE. Characteristics and management of mirror syndrome: a systematic review (1956-2016). J Perinat Med. 2017;45(9):1013–21.

Eiland S, Cvetanovska E, Bjerre AH, Nyholm H, Sundberg K, Nørgaard LN. Mirror syndrome is a rare complication in pregnancy, characterized by oedema and hydrops fetalis. Ugeskr Laeger. 2017;10:179(15).

Iciek R, Brazert M, Klejewski A, Pietryga M, Ballantyne Syndrome BJ. (Mirror syndrome) associated with severe non-immune fetal hydrops. A case report. Ginekol Pol. 2015;86(9):706–11.

Xu Z, Huan Y, Zhang Y, Liu Z. Anesthetic management of a parturient with mirror syndrome: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(8):14161–5.

Okby R, Mazor M, Erez O, Beer-Weizel R, Hershkovitz R. Reversal of mirror syndrome after selective feticide of a hydropic fetus in a dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(2):351–3.

Acknowledgements

All persons that contributed to this study are listed authors and meet the criteria for authorship.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC, LG-D and GA drafted the manuscript, and AMC and MMD collaborated with valuable contributions to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Consent for publication

Written and verbal consent for publication was obtained from all four patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chimenea, A., García-Díaz, L., Calderón, A.M. et al. Resolution of maternal Mirror syndrome after succesful fetal intrauterine therapy: a case series. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 85 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1718-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1718-0